Ordovician

| Ordovician | |

|---|---|

| Lower GSSP ratified | 2000[5] |

| Upper boundary definition | FAD of the Graptolite Akidograptus ascensus |

| Upper boundary GSSP | Dob's Linn, Moffat, U.K. 55°26′24″N 3°16′12″W / 55.4400°N 3.2700°W |

| Upper GSSP ratified | 1984[6][7] |

| Atmospheric and climatic data | |

| Sea level above present day | 180 m; rising to 220 m in Caradoc and falling sharply to 140 m in end-Ordovician glaciations[8] |

The Ordovician (

The Ordovician, named after the Welsh tribe of the Ordovices, was defined by Charles Lapworth in 1879 to resolve a dispute between followers of Adam Sedgwick and Roderick Murchison, who were placing the same rock beds in North Wales in the Cambrian and Silurian systems, respectively.[11] Lapworth recognized that the fossil fauna in the disputed strata were different from those of either the Cambrian or the Silurian systems, and placed them in a system of their own. The Ordovician received international approval in 1960 (forty years after Lapworth's death), when it was adopted as an official period of the Paleozoic Era by the International Geological Congress.

Life continued to flourish during the Ordovician as it did in the earlier Cambrian Period, although the end of the period was marked by the

Subdivisions

A number of regional terms have been used to subdivide the Ordovician Period. In 2008, the ICS erected a formal international system of subdivisions.[13] There exist Baltoscandic, British, Siberian, North American, Australian, Chinese, Mediterranean and North-Gondwanan regional stratigraphic schemes.[14]

ICS (global) subdivisions

- Upper Ordovician epoch (458.4 Ma – 443.8 Ma)

- Hirnantian stage/age (445.2 Ma – 443.8 Ma)

- Katian stage/age (453.0 Ma – 445.2 Ma)

- Sandbian stage/age (458.4 Ma – 453.0 Ma)

- Middle Ordovician epoch (470.0 Ma – 458.4 Ma)

- Darriwilian stage/age (467.3 Ma – 458.4 Ma)

- Dapingian stage/age (470.0 Ma – 467.3 Ma)

- Lower Ordovician epoch (485.4 Ma – 470.0 Ma)

- Floian stage/age (477.7 Ma – 470.0 Ma)

- Tremadocian stage/age (485.4 Ma – 477.7 Ma)

British stages and ages

The Ordovician Period in Britain was traditionally broken into Early (Tremadocian and Arenig), Middle (Llanvirn (subdivided into Abereiddian and Llandeilian) and Llandeilo) and Late (Caradoc and Ashgill) epochs. The corresponding rocks of the Ordovician System are referred to as coming from the Lower, Middle, or Upper part of the column.

The Tremadoc corresponds to the (modern) Tremadocian. The Floian corresponds to the early Arenig; the Arenig continues until the early Darriwilian, subsuming the Dapingian. The Llanvirn occupies the rest of the Darriwilian, and terminates with it at the start of the Late Ordovician. The Sandbian represents the first half of the Caradoc; the Caradoc ends in the mid-Katian, and the Ashgill represents the last half of the Katian, plus the Hirnantian.

The British

"Late Ordovician"

- Hirnantian/Gamach (Ashgill)

- Rawtheyan/Richmond (Ashgill)

- Cautleyan/Richmond (Ashgill)

- Pusgillian/Maysville/Richmond (Ashgill)

"Middle Ordovician"

- Trenton (Caradoc)

- Onnian/Maysville/Eden (Caradoc)

- Actonian/Eden (Caradoc)

- Marshbrookian/Sherman (Caradoc)

- Longvillian/Sherman (Caradoc)

- Soudleyan/Kirkfield (Caradoc)

- Harnagian/Rockland (Caradoc)

- Costonian/Black River (Caradoc)

- Chazy (Llandeilo)

- Llandeilo (Llandeilo)

- Whiterock (Llanvirn)

- Llanvirn (Llanvirn)

"Early Ordovician"

- Cassinian (Arenig)

- Arenig/Jefferson/Castleman (Arenig)

- Tremadoc/Deming/Gaconadian (Tremadoc)

The Tremadoc corresponds to the (modern) Tremadocian. The Floian corresponds to the lower Arenig; the Arenig continues until the early Darriwilian, subsuming the Dapingian. The Llanvirn occupies the rest of the Darriwilian, and terminates with it at the base of the Late Ordovician. The Sandbian represents the first half of the Caradoc; the Caradoc ends in the mid-Katian, and the Ashgill represents the last half of the Katian, plus the Hirnantian.[15]

| ICS series | ICS stage | British series | British stage | North American series | North American stage | Australian stage | Chinese stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Upper Ordovician |

Hirnantian | Ashgill | Hirnantian | Cincinnatian | Gamachian | Bolindian | Hirnantian |

| Katian | Rawtheyan | Richmondian | Chientangkiangian | ||||

| Cautleyan | |||||||

| Pusgillian | Maysvillian | Eastonian | Neichianshanian | ||||

Caradoc |

Streffordian | Edenian | |||||

| Cheneyan | Mohawkian | Chatfieldian | |||||

| Sandbian | Burrellian | Gisbornian | |||||

| Turinian | |||||||

| Aurelucian | |||||||

Whiterockian

|

|||||||

Middle Ordovician |

Darriwilian | Llanvirn |

Llandeilo | Darriwilian | Darriwilian | ||

| Abereiddian | |||||||

| Arenig | Fennian | ||||||

| Dapingian | Yapeenian | Dapingian | |||||

| Whitlandian | Rangerian | Castlemainian | |||||

Lower Ordovician

|

Floian | Ibexian | Blackhillsian | Chewtonian | Yiyangian | ||

| Bendigonian | |||||||

| Moridunian | |||||||

| Tulean | Lancefieldian | ||||||

| Tremadocian | Tremadoc | Migneintian | Xinchangian | ||||

| Stairsian | |||||||

| Cressagian | |||||||

| Skullrockian | |||||||

| Warendan |

Paleogeography and tectonics

During the Ordovician, the southern continents were assembled into Gondwana, which reached from north of the equator to the South Pole. The Panthalassic Ocean, centered in the northern hemisphere, covered over half the globe.[17] At the start of the period, the continents of Laurentia (in present-day North America), Siberia, and Baltica (present-day northern Europe) were separated from Gondwana by over 5,000 kilometres (3,100 mi) of ocean. These smaller continents were also sufficiently widely separated from each other to develop distinct communities of benthic organisms.[18] The small continent of Avalonia had just rifted from Gondwana and began to move north towards Baltica and Laurentia, opening the Rheic Ocean between Gondwana and Avalonia.[19][20][21] Avalonia collided with Baltica towards the end of Ordovician.[22][23]

Other geographic features of the Ordovician world included the Tornquist Sea, which separated Avalonia from Baltica;[18] the Aegir Ocean, which separated Baltica from Siberia;[24] and an oceanic area between Siberia, Baltica, and Gondwana which expanded to become the Paleoasian Ocean in Carboniferous time. The Mongol-Okhotsk Ocean formed a deep embayment between Siberia and the Central Mongolian terranes. Most of the terranes of central Asia were part of an equatorial archipelago whose geometry is poorly constrained by the available evidence.[25]

The period was one of extensive, widespread tectonism and volcanism. However,

The Taconic orogeny, a major mountain-building episode, was well under way in Cambrian times.[27] This continued into the Ordovician, when at least two volcanic island arcs collided with Laurentia to form the Appalachian Mountains. Laurentia was otherwise tectonically stable. An island arc accreted to South China during the period, while subduction along north China (Sulinheer) resulted in the emplacement of ophiolites.[28]

The

There was vigorous tectonic activity along northwest margin of Gondwana during the Floian, 478 Ma, recorded in the Central Iberian Zone of Spain. The activity reached as far as Turkey by the end of Ordovician. The opposite margin of Gondwana, in Australia, faced a set of island arcs.[18] The accretion of these arcs to the eastern margin of Gondwana was responsible for the Benambran Orogeny of eastern Australia.[30][31] Subduction also took place along what is now Argentina (Famatinian Orogeny) at 450 Ma.[32] This involved significant back arc rifting.[18] The interior of Gondwana was tectonically quiet until the Triassic.[18]

Towards the end of the period, Gondwana began to drift across the South Pole. This contributed to the Hibernian glaciation and the associated extinction event.[33]

Ordovician meteor event

The Ordovician meteor event is a proposed shower of meteors that occurred during the Middle Ordovician Epoch, about 467.5 ± 0.28 million years ago, due to the break-up of the L chondrite parent body.[34] It is not associated with any major extinction event.[35][36][37]

Geochemistry

The Ordovician was a time of calcite sea geochemistry in which low-magnesium calcite was the primary inorganic marine precipitate of calcium carbonate.[38] Carbonate hardgrounds were thus very common, along with calcitic ooids, calcitic cements, and invertebrate faunas with dominantly calcitic skeletons. Biogenic aragonite, like that composing the shells of most molluscs, dissolved rapidly on the sea floor after death.[39][40]

Unlike Cambrian times, when calcite production was dominated by microbial and non-biological processes, animals (and macroalgae) became a dominant source of calcareous material in Ordovician deposits.[41]

Climate and sea level

The Early Ordovician climate was very hot,

The Ordovician saw the highest sea levels of the Paleozoic, and the low relief of the continents led to many shelf deposits being formed under hundreds of metres of water.[41] The sea level rose more or less continuously throughout the Early Ordovician, leveling off somewhat during the middle of the period.[41] Locally, some regressions occurred, but the sea level rise continued in the beginning of the Late Ordovician. Sea levels fell steadily due to the cooling temperatures for about 3 million years leading up to the Hirnantian glaciation. During this icy stage, sea level seems to have risen and dropped somewhat. Despite much study, the details remain unresolved.[41] In particular, some researches interpret the fluctuations in sea level as pre-Hibernian glaciation,[52] but sedimentary evidence of glaciation is lacking until the end of the period.[23] There is evidence of glaciers during the Hirnantian on the land we now know as Africa and South America, which were near the South Pole at the time, facilitating the formation of the ice caps of the Hirnantian glaciation.

As with

Life

For most of the Late Ordovician life continued to flourish, but at and near the end of the period there were

Fauna

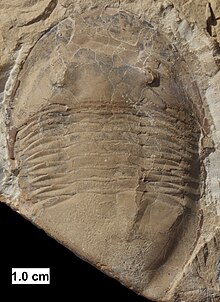

On the whole, the fauna that emerged in the Ordovician were the template for the remainder of the Palaeozoic. The fauna was dominated by tiered communities of suspension feeders, mainly with short food chains. The ecological system reached a new grade of complexity far beyond that of the Cambrian fauna, which has persisted until the present day. Ordovician geography had its effect on the diversity of fauna; Ordovician invertebrates displayed a very high degree of provincialism.[57] The widely separated continents of Laurentia and Baltica, then positioned close to the tropics and boasting many shallow seas rich in life, developed distinct trilobite faunas from the trilobite fauna of Gondwana,[58] and Gondwana developed distinct fauna in its tropical and temperature zones.[59] The Tien Shan terrane maintained a biogeographic affinity with Gondwana,[60] and the Alborz margin of Gondwana was linked biogeographically to South China.[61] Southeast Asia's fauna also maintained strong affinities to Gondwana's.[62] North China was biogeographically connected to Laurentia and the Argentinian margin of Gondwana.[63] A Celtic biogeographic province also existed, separate from the Laurentian and Baltican ones.[64] However, tropical articulate brachiopods had a more cosmopolitan distribution, with less diversity on different continents. During the Middle Ordovician, beta diversity began a significant decline as marine taxa began to disperse widely across space.[65] Faunas become less provincial later in the Ordovician, partly due to the narrowing of the Iapetus Ocean,[66] though they were still distinguishable into the late Ordovician.[67]

In the Early Ordovician, trilobites were joined by many new types of organisms, including

In the Middle Ordovician, the trilobite-dominated Early Ordovician communities were replaced by generally more mixed ecosystems, in which brachiopods, bryozoans, molluscs, cornulitids, tentaculitids and echinoderms all flourished, tabulate corals diversified and the first rugose corals appeared. The planktonic graptolites remained diverse, with the Diplograptina making their appearance. One of the earliest known armoured agnathan ("ostracoderm") vertebrates, Arandaspis, dates from the Middle Ordovician.[88] During the Middle Ordovician there was a large increase in the intensity and diversity of bioeroding organisms. This is known as the Ordovician Bioerosion Revolution.[89] It is marked by a sudden abundance of hard substrate trace fossils such as Trypanites, Palaeosabella, Petroxestes and Osprioneides. Bioerosion became an important process, particularly in the thick calcitic skeletons of corals, bryozoans and brachiopods, and on the extensive carbonate hardgrounds that appear in abundance at this time.

-

Upper OrdovicianbryozoanCorynotrypa in the background

-

Middle Ordovician fossiliferous shales and limestones at Fossil Mountain, west-central Utah

-

Outcrop of Upper Ordovician rubbly limestone and shale, southern Indiana

-

Outcrop of Upper Ordovician limestone and minor shale, central Tennessee

-

hardground, southeastern Indiana[90]

-

hardground, southern Ohio[89]

-

Brachiopods and bryozoans in an Ordovician limestone, southern Minnesota

-

Vinlandostrophia ponderosa, Maysvillian (Upper Ordovician) near Madison, Indiana (scale bar is 5.0 mm)

-

The Ordovician cystoid Echinosphaerites (an extinct echinoderm) from northeastern Estonia; approximately 5 cm in diameter

-

Prasopora, a trepostomebryozoanfrom the Ordovician of Iowa

-

An Ordovician strophomenid brachiopod with encrusting inarticulate brachiopods and a bryozoan

-

The heliolitid coral Protaraea richmondensis encrusting a gastropod; Cincinnatian (Upper Ordovician) of southeastern Indiana

-

Zygospira modesta, atrypid brachiopods, preserved in their original positions on a trepostome bryozoan from the Cincinnatian (Upper Ordovician) of southeastern Indiana

-

Graptolites (Amplexograptus) from the Ordovician near Caney Springs, Tennessee

Flora

Among the first land

End of the period

The Ordovician came to a close in a series of extinction events that, taken together, comprise the second largest of the five major extinction events in Earth's history in terms of percentage of genera that became extinct. The only larger one was the Permian–Triassic extinction event.

The extinctions occurred approximately 447–444 million years ago and mark the boundary between the Ordovician and the following

The most commonly accepted theory is that these events were triggered by the onset of cold conditions in the late Katian, followed by an ice age, in the Hirnantian faunal stage, that ended the long, stable greenhouse conditions typical of the Ordovician.

The ice age was possibly not long-lasting. Oxygen

The

As glaciers grew, the sea level dropped, and the vast shallow intra-continental Ordovician seas withdrew, which eliminated many ecological niches. When they returned, they carried diminished founder populations that lacked many whole families of organisms. They then withdrew again with the next pulse of glaciation, eliminating biological diversity with each change.[97] Species limited to a single epicontinental sea on a given landmass were severely affected.[40] Tropical lifeforms were hit particularly hard in the first wave of extinction, while cool-water species were hit worst in the second pulse.[40]

Those species able to adapt to the changing conditions survived to fill the ecological niches left by the extinctions. For example, there is evidence the oceans became more deeply oxygenated during the glaciation, allowing unusual benthic organisms (Hirnantian fauna) to colonize the depths. These organisms were cosmopolitan in distribution and present at most latitudes.[67]

At the end of the second event, melting glaciers caused the sea level to rise and stabilise once more. The rebound of life's diversity with the permanent re-flooding of continental shelves at the onset of the Silurian saw increased biodiversity within the surviving Orders. Recovery was characterized by an unusual number of "Lazarus taxa", disappearing during the extinction and reappearing well into the Silurian, which suggests that the taxa survived in small numbers in refugia.[98]

An alternate extinction hypothesis suggested that a ten-second gamma-ray burst could have destroyed the ozone layer and exposed terrestrial and marine surface-dwelling life to deadly ultraviolet radiation and initiated global cooling.[99]

Recent work considering the sequence stratigraphy of the Late Ordovician argues that the mass extinction was a single protracted episode lasting several hundred thousand years, with abrupt changes in water depth and sedimentation rate producing two pulses of last occurrences of species.[100]

References

- PMID 10905606.

- .

- PMID 28117834.

It has been suggested that the Middle Ordovician meteorite bombardment played a crucial role in the Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event, but this study shows that the two phenomena were unrelated

- ^ "Chart/Time Scale". www.stratigraphy.org. International Commission on Stratigraphy.

- . Retrieved 6 December 2020.

- .

- . Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- S2CID 206514545.

- ^ "Ordovician". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d.

- ^ "International Chronostratigraphic Chart v.2015/01" (PDF). International Commission on Stratigraphy. January 2015.

- ^ Charles Lapworth (1879) "On the Tripartite Classification of the Lower Palaeozoic Rocks"[permanent dead link], Geological Magazine, new series, 6 : 1-15. From pp. 13-14: "North Wales itself — at all events the whole of the great Bala district where Sedgwick first worked out the physical succession among the rocks of the intermediate or so-called Upper Cambrian or Lower Silurian system; and in all probability, much of the Shelve and the Caradoc area, whence Murchison first published its distinctive fossils — lay within the territory of the Ordovices; … Here, then, have we the hint for the appropriate title for the central system of the Lower Paleozoic. It should be called the Ordovician System, after this old British tribe."

- ^ "New type of meteorite linked to ancient asteroid collision". Science Daily. 15 June 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- .

- ^ "The Ordovician Period". Subcommission on Ordovician Stratigraphy. International Commission on Stratigraphy. 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2021.

- ^ Ogg; Ogg; Gradstein, eds. (2008). The Concise Geological Timescale.

- ISBN 978-0-12-824360-2, retrieved 2023-06-08

- ISBN 9781107105324.

- ^ a b c d e f g Torsvik & Cocks 2017, p. 102.

- S2CID 129091590.

- .

- ^ Torsvik & Cocks 2017, p. 103.

- . Retrieved 21 May 2023.

- ^ a b c Torsvik & Cocks 2017, p. 112.

- S2CID 54656066.

- ^ Torsvik & Cocks 2017, pp. 102, 106.

- ISBN 9780813724669.

- ^ Torsvik & Cocks 2017, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Torsvik & Cocks 2017, pp. 106–109.

- .

- S2CID 129843558.

- ^ Torsvik & Cocks 2017, p. 105.

- ISBN 978-3-319-67773-6.

- ^ Torsvik & Cocks 2017, pp. 103–105.

- PMID 28117834.

- S2CID 4393398.

- .

- S2CID 54513002.

- S2CID 213408515.

- .

- ^ a b c Stanley, S. M.; Hardie, L. A. (1999). "Hypercalcification; paleontology links plate tectonics and geochemistry to sedimentology". GSA Today. 9: 1–7.

- ^ . Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ISSN 0012-821X. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- .

- ISSN 0091-7613. Retrieved 30 September 2023.

- ^ .

- PMID 33526667.

- . Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- . Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- S2CID 133243759.

- doi:10.1130/G21180.1.

- S2CID 28224399.

- PMID 26733399.

- ^ "Humble moss helped to cool Earth and spurred on life". BBC News. 2 February 2012.

- ISBN 978-0-7607-1957-2.

- ^ Palaeos Paleozoic : Ordovician : The Ordovician Period Archived 21 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ISBN 978-0-675-20140-7.

- . Retrieved 18 May 2023.

- hdl:10852/83447. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ISSN 0435-4052. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- . Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ^ Ghobadi Pour, M.; Popov, L. E.; Álvaro, J. J.; Amini, A.; Hairapetian, V.; Jahangir, H. (23 December 2022). "Ordovician of North Iran: New lithostratigraphy, palaeogeography and biogeographical links with South China and the Mediterranean peri-Gondwana margin". Bulletin of Geosciences. 97 (4): 465–538. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- . Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ISSN 0435-4052. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- . Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- hdl:10138/325369. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ISSN 0954-4879. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- ^ a b Torsvik & Cocks 2017, p. 112-113.

- ^ "Palaeos Paleozoic : Ordovician : The Ordovician Period". April 11, 2002. Archived from the original on December 21, 2007.

- ^ "A Guide to the Orders of Trilobites".

- PMID 24726154.

- S2CID 129113026.

- S2CID 140593975.

- S2CID 213757467. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- . Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- S2CID 130038222. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- . Retrieved 23 July 2023.

- S2CID 85724505. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- S2CID 83933056. Retrieved 8 December 2022.

- .

- . Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- S2CID 129733589.

- ^ "12.7: Vertebrate Evolution". Biology LibreTexts. 2016-10-05. Retrieved 2022-06-07.

- PMID 25903631.

- S2CID 135138918. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- . Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- . Retrieved 2014-06-11.

- . Retrieved 2014-01-09.

- . Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ S2CID 128831144. Archived from the original(PDF) on 2008-12-16.

- S2CID 130036115.

- ^ PMID 27385026.

- S2CID 206518080.

- S2CID 43553633.

- ISBN 978-0-7167-2882-5.

- .

- ^ a b Jeff Hecht, High-carbon ice age mystery solved, New Scientist, 8 March 2010 (retrieved 30 June 2014)

- ^ Emiliani, Cesare. (1992). Planet Earth : Cosmology, Geology, & the Evolution of Life & the Environment (Cambridge University Press) p. 491

- ^ Torsvik & Cocks 2017, pp. 122–123.

- S2CID 13124815.

- S2CID 129522636.

External links

- Ogg, Jim (June 2004). "Overview of Global Boundary Stratotype Sections and Points (GSSP's)". Archived from the original on 2006-04-23. Retrieved 2006-04-30.

- Mehrtens, Charlotte. "Chazy Reef at Isle La Motte". An Ordovician reef in Vermont.

- Ordovician fossils of the famous Cincinnatian Group

- Ordovician (chronostratigraphy scale)

![Trypanites borings in an Ordovician hardground, southeastern Indiana[90]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/27/LibertyBorings.jpg/120px-LibertyBorings.jpg)

![Petroxestes borings in an Ordovician hardground, southern Ohio[89]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b9/Petroxestes_borings_Ordovician.jpg/82px-Petroxestes_borings_Ordovician.jpg)