Osteoarthritis

| Osteoarthritis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Arthrosis, osteoarthrosis, degenerative arthritis, degenerative joint disease |

| Usual onset | Over years[1] |

| Causes | Connective tissue disease, previous joint injury, abnormal joint or limb development, inherited factors[1][2] |

| Risk factors | Overweight, legs of different lengths, job with high levels of joint stress[1][2] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms, supported by other testing[1] |

| Treatment | Exercise, efforts to decrease joint stress, support groups, pain medications, joint replacement[1][2][3] |

| Frequency | 237 million / 3.3% (2015)[4] |

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a type of degenerative

Causes include previous joint injury, abnormal joint or limb development, and inherited factors.[1][2] Risk is greater in those who are overweight, have legs of different lengths, or have jobs that result in high levels of joint stress.[1][2][8] Osteoarthritis is believed to be caused by mechanical stress on the joint and low grade inflammatory processes.[9] It develops as cartilage is lost and the underlying bone becomes affected.[1] As pain may make it difficult to exercise, muscle loss may occur.[2][10] Diagnosis is typically based on signs and symptoms, with medical imaging and other tests used to support or rule out other problems.[1] In contrast to rheumatoid arthritis, in osteoarthritis the joints do not become hot or red.[1]

Treatment includes exercise, decreasing joint stress such as by rest or use of a

Osteoarthritis is the most common form of arthritis, affecting about 237 million people or 3.3% of the world's population, as of 2015.

Signs and symptoms

The main symptom is

Osteoarthritis commonly affects the hands, feet,

In smaller joints, such as at the fingers, hard bony enlargements, called

Causes

Damage from mechanical stress with insufficient self repair by joints is believed to be the primary cause of osteoarthritis.

Primary

The development of osteoarthritis is correlated with a history of previous joint injury and with obesity, especially with respect to knees.[21] Changes in sex hormone levels may play a role in the development of osteoarthritis, as it is more prevalent among post-menopausal women than among men of the same age.[1][22] Conflicting evidence exists for the differences in hip and knee osteoarthritis in African Americans and Caucasians.[23]

Occupational

Increased risk of developing knee and hip osteoarthritis was found among those who work with manual handling (e.g. lifting), have physically demanding work, walk at work, and have climbing tasks at work (e.g. climb stairs or ladders).[8] With hip osteoarthritis, in particular, increased risk of development over time was found among those who work in bent or twisted positions.[8] For knee osteoarthritis, in particular, increased risk was found among those who work in a kneeling or squatting position, experience heavy lifting in combination with a kneeling or squatting posture, and work standing up.[8] Women and men have similar occupational risks for the development of osteoarthritis.[8]

Secondary

This type of osteoarthritis is caused by other factors but the resulting pathology is the same as for primary osteoarthritis:

- Alkaptonuria[24]

- Diabetes doubles the risk of having a joint replacement due to osteoarthritis and people with diabetes have joint replacements at a younger age than those without diabetes.[27]

- Ehlers-Danlos syndrome[28]

- Hemochromatosis and Wilson's disease[29]

- Inflammatory diseases (such as Perthes' disease), (Lyme disease), and all chronic forms of arthritis (e.g., costochondritis, gout, and rheumatoid arthritis). In gout, uric acidcrystals cause the cartilage to degenerate at a faster pace.

- Injury to joints or ligaments (such as the ACL) as a result of an accident or orthopedic operations.

- Ligamentous deterioration or instability may be a factor.

- Marfan syndrome[30]

- Obesity[31]

- Joint infection[32][33][34]

Pathophysiology

While osteoarthritis is a degenerative joint disease that may cause gross cartilage loss and morphological damage to other joint tissues, more subtle biochemical changes occur in the earliest stages of osteoarthritis progression. The water content of healthy cartilage is finely balanced by compressive force driving water out and

However, during onset of osteoarthritis, the collagen matrix becomes more disorganized and there is a decrease in proteoglycan content within cartilage. The breakdown of collagen fibers results in a net increase in water content.[38][39][40][41][42] This increase occurs because whilst there is an overall loss of proteoglycans (and thus a decreased osmotic pull),[39][43] it is outweighed by a loss of collagen.[37][43]

Other structures within the joint can also be affected.

Diagnosis

| Type | WBC (per mm3) | % neutrophils | Viscosity | Appearance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | <200 | 0 | High | Transparent |

| Osteoarthritis | <5000 | <25 | High | Clear yellow |

| Trauma | <10,000 | <50 | Variable | Bloody |

| Inflammatory | 2,000–50,000 | 50–80 | Low | Cloudy yellow |

| Septic arthritis | >50,000 | >75 | Low | Cloudy yellow |

| Gonorrhea | ~10,000 | 60 | Low | Cloudy yellow |

| Tuberculosis | ~20,000 | 70 | Low | Cloudy yellow |

| Inflammatory: Arthritis, gout, rheumatoid arthritis, rheumatic fever | ||||

Diagnosis is made with reasonable certainty based on history and clinical examination.

In 1990, the

-

Severe osteoarthritis and osteopenia of the carpal joint and 1st carpometacarpal joint

-

MRI of osteoarthritis in the knee, with characteristic narrowing of the joint space

-

Primary osteoarthritis of the left knee. Note theosteophytes, narrowing of the joint space (arrow), and increased subchondral bone density (arrow).

-

Damaged cartilage from sows. (a) cartilage erosion (b)cartilage ulceration (c)cartilage repair (d)osteophyte (bone spur) formation.

-

Histopathology of osteoarthrosis of a knee joint in an elderly female

-

Histopathology of osteoarthrosis of a knee joint in an elderly female

-

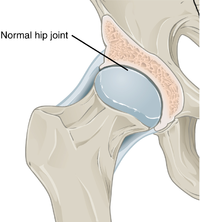

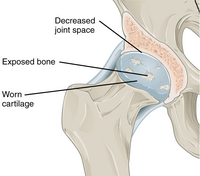

In a healthy joint, the ends of bones are encased in smooth cartilage. Together, they are protected by a joint capsule lined with a synovial membrane that produces synovial fluid. The capsule and fluid protect the cartilage, muscles, and connective tissues.

-

With osteoarthritis, the cartilage becomes worn away. Spurs grow out from the edge of the bone, and synovial fluid increases. Altogether, the joint feels stiff and sore.

-

Osteoarthritis

-

Bone (left) and clinical (right) changes of the hand in osteoarthritis

Classification

A number of classification systems are used for gradation of osteoarthritis:

- WOMAC scale, taking into account pain, stiffness and functional limitation.[57]

- Kellgren-Lawrence grading scale for osteoarthritis of the knee. It uses only projectional radiographyfeatures.

- hip joint, also using only projectional radiography features.[58]

Both primary generalized nodal osteoarthritis and erosive osteoarthritis (EOA, also called inflammatory osteoarthritis) are sub-sets of primary osteoarthritis. EOA is a much less common, and more aggressive inflammatory form of osteoarthritis which often affects the distal interphalangeal joints of the hand and has characteristic articular erosive changes on X-ray.[59]

Management

Lifestyle modification (such as weight loss and exercise) and

Successful management of the condition is often made more difficult by differing priorities and poor communication between clinicians and people with osteoarthritis. Realistic treatment goals can be achieved by developing a shared understanding of the condition, actively listening to patient concerns, avoiding medical jargon and tailoring treatment plans to the patient's needs.[65][66]

Exercise

Weight loss and exercise provide long-term treatment and are advocated in people with osteoarthritis.[67] Weight loss and exercise are the most safe and effective long-term treatments, in contrast to short-term treatments which usually have risk of long-term harm.[68]

High impact exercise can increase the risk of joint injury, whereas low or moderate impact exercise, such as walking or swimming, is safer for people with osteoarthritis.[67] A study has suggested that an increase in blood calcium levels had a positive impact on osteoarthritis. An adequate dietary calcium intake and regular weight-bearing exercise can increase calcium levels and is helpful in preventing osteoarthritis in the general population. There is also a weak protective effect factor of LDL (low-density lipoprotein) cholesterol. However, this is not recommended since an increase in LDL has an increased chance of cardiovascular comorbidities.[69]

Moderate exercise may be beneficial with respect to pain and function in those with osteoarthritis of the knee and hip.[70][71][72] These exercises should occur at least three times per week, under supervision, and focused on specific forms of exercise found to be most beneficial for this form of osteoarthritis.[73]

While some evidence supports certain physical therapies, evidence for a combined program is limited.[74] Providing clear advice, making exercises enjoyable, and reassuring people about the importance of doing exercises may lead to greater benefit and more participation.[72] Some evidence suggests that supervised exercise therapy may improve exercise adherence,[75], although for knee osteoarthritis supervised exercise has shown the best results.[73]

Physical measures

There is not enough evidence to determine the effectiveness of

Functional, gait, and balance training have been recommended to address impairments of position sense, balance, and strength in individuals with lower extremity arthritis, as these can contribute to a higher rate of falls in older individuals.[79][80] For people with hand osteoarthritis, exercises may provide small benefits for improving hand function, reducing pain, and relieving finger joint stiffness.[81]

A study showed that there is low quality evidence that weak knee extensor muscle increased the chances of knee osteoarthritis. Strengthening of the knee extensors could possibly prevent knee osteoarthritis.[82]

Lateral wedge insoles and neutral insoles do not appear to be useful in osteoarthritis of the knee.[83][84][85] Knee braces may help[86] but their usefulness has also been disputed.[85] For pain management heat can be used to relieve stiffness, and cold can relieve muscle spasms and pain.[87] Among people with hip and knee osteoarthritis, exercise in water may reduce pain and disability, and increase quality of life in the short term.[88] Also therapeutic exercise programs such as aerobics and walking reduce pain and improve physical functioning for up to 6 months after the end of the program for people with knee osteoarthritis.[89] In a study conducted over a period of 2 years on a group of individuals, a research team found that for every additional 1,000 steps per day, there was a 16% reduction in functional limitations in cases of knee osteoarthritis.[90] Hydrotherapy might also be an advantage on the management of pain, disability and quality of life reported by people with osteoarthritis.[91]

Thermotherapy

A 2003

Medication

| Treatment recommendations by risk factors | ||

|---|---|---|

| GI risk | CVD risk | Option |

| Low | Low | NSAID, or paracetamol[93] |

| Moderate | Low | Paracetamol, or low dose NSAID with antacid[93] |

| Low | Moderate | Paracetamol, or low dose aspirin with an antacid[93] |

| Moderate | Moderate | Low dose paracetamol, aspirin, and antacid. Monitoring for abdominal pain or black stool.[93] |

By mouth

The

Another class of NSAIDs,

Education is helpful in self-management of arthritis, and can provide coping methods leading to about 20% more pain relief when compared to NSAIDs alone.[63]

Failure to achieve desired pain relief in osteoarthritis after two weeks should trigger reassessment of dosage and pain medication.

Use of the antibiotic doxycycline orally for treating osteoarthritis is not associated with clinical improvements in function or joint pain.[106] Any small benefit related to the potential for doxycycline therapy to address the narrowing of the joint space is not clear, and any benefit is outweighed by the potential harm from side effects.[106]

A 2018 meta-analysis found that oral collagen supplementation for the treatment of osteoarthritis reduces stiffness but does not improve pain and functional limitation.[107]

Topical

There are several NSAIDs available for

Joint injections

Use of analgesia, intra-articular cortisone injection and consideration of hyaluronic acids and platelet-rich plasma are recommended for pain relief in people with knee osteoarthritis.[112]

Local drug delivery by intra-articular injection may be more effective and safer in terms of increased bioavailability, less systemic exposure and reduced adverse events.[113] Several intra-articular medications for symptomatic treatment are available on the market as follows.[114]

Steroids

Joint injection of glucocorticoids (such as hydrocortisone) leads to short-term pain relief that may last between a few weeks and a few months.[115] A 2015 Cochrane review found that intra-articular corticosteroid injections of the knee did not benefit quality of life and had no effect on knee joint space; clinical effects one to six weeks after injection could not be determined clearly due to poor study quality.[116] Another 2015 study reported negative effects of intra-articular corticosteroid injections at higher doses,[117] and a 2017 trial showed reduction in cartilage thickness with intra-articular triamcinolone every 12 weeks for 2 years compared to placebo.[118] A 2018 study found that intra-articular triamcinolone is associated with an increase in intraocular pressure.[119]

Hyaluronic acid

Injections of hyaluronic acid have not produced improvement compared to placebo for knee arthritis,[120][121] but did increase risk of further pain.[120] In ankle osteoarthritis, evidence is unclear.[122]

Radiosynoviorthesis

Injection of beta particle-emitting radioisotopes (called radiosynoviorthesis) is used for the local treatment of inflammatory joint conditions.[123]

Platelet-rich plasma

The effectiveness of injections of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is unclear; there are suggestions that such injections improve function but not pain, and are associated with increased risk.[vague][124][125] A 2014 Cochrane review of studies involving PRP found the evidence to be insufficient.[126]

Surgery

Bone fusion

Arthrodesis (fusion) of the bones may be an option in some types of osteoarthritis. An example is ankle osteoarthritis, in which ankle fusion is considered to be the gold standard treatment in end-stage cases.[127]

Joint replacement

If the impact of symptoms of osteoarthritis on quality of life is significant and more conservative management is ineffective,

For people who have shoulder osteoarthritis and do not respond to medications, surgical options include a shoulder hemiarthroplasty (replacing a part of the joint), and total shoulder arthroplasty (replacing the joint).[135]

Biological joint replacement involves replacing the diseased tissues with new ones. This can either be from the person (autograft) or from a donor (allograft).[136] People undergoing a joint transplant (osteochondral allograft) do not need to take immunosuppressants as bone and cartilage tissues have limited immune responses.[137] Autologous articular cartilage transfer from a non-weight-bearing area to the damaged area, called osteochondral autograft transfer system, is one possible procedure that is being studied.[138] When the missing cartilage is a focal defect, autologous chondrocyte implantation is also an option.[139]

Shoulder replacement

For those with osteoarthritis in the shoulder, a complete shoulder replacement is sometimes suggested to improve pain and function.[140] Demand for this treatment is expected to increase by 750% by the year 2030.[140] There are different options for shoulder replacement surgeries, however, there is a lack of evidence in the form of high-quality randomized controlled trials, to determine which type of shoulder replacement surgery is most effective in different situations, what are the risks involved with different approaches, or how the procedure compares to other treatment options.[140][141] There is some low-quality evidence that indicates that when comparing total shoulder arthroplasty over hemiarthroplasty, no large clinical benefit was detected in the short term.[141] It is not clear if the risk of harm differs between total shoulder arthroplasty or a hemiarthroplasty approach.[141]

Other surgical options

Unverified treatments

Glucosamine and chondroitin

The effectiveness of glucosamine is controversial.[147] Reviews have found it to be equal to[148][149] or slightly better than placebo.[150][151] A difference may exist between glucosamine sulfate and glucosamine hydrochloride, with glucosamine sulfate showing a benefit and glucosamine hydrochloride not.[152] The evidence for glucosamine sulfate having an effect on osteoarthritis progression is somewhat unclear and if present likely modest.[153] The Osteoarthritis Research Society International recommends that glucosamine be discontinued if no effect is observed after six months[154] and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence no longer recommends its use.[10] Despite the difficulty in determining the efficacy of glucosamine, it remains a treatment option.[155] The European Society for Clinical and Economic Aspects of Osteoporosis and Osteoarthritis (ESCEO) recommends glucosamine sulfate and chondroitin sulfate for knee osteoarthritis.[156] Its use as a therapy for osteoarthritis is usually safe.[155][157]

A 2015 Cochrane review of clinical trials of chondroitin found that most were of low quality, but that there was some evidence of short-term improvement in pain and few side effects; it does not appear to improve or maintain the health of affected joints.[158]

Supplements

Avocado–soybean

A few high-quality studies of

There is limited evidence to support the use of

Acupuncture and other interventions

While acupuncture leads to improvements in pain relief, this improvement is small and may be of questionable importance.[168] Waiting list–controlled trials for peripheral joint osteoarthritis do show clinically relevant benefits, but these may be due to placebo effects.[169][170] Acupuncture does not seem to produce long-term benefits.[171]

Further research is needed to determine if

There is low quality evidence that therapeutic ultrasound may be beneficial for people with osteoarthritis of the knee; however, further research is needed to confirm and determine the degree and significance of this potential benefit.[177]

Therapeutic ultrasound may relieve pain compared to conventional non-drug ultrasound however phonopheresis does not produce additional benefits to functional improvement. It is safe treatment to relieve pain and improve physical function in patients with knee osteoarthritis.[178]

Continuous and pulsed ultrasound modes (especially 1 MHz, 2.5 W/cm2, 15min/ session, 3 session/ week, during 8 weeks protocol) may be effective in improving patients physical function and pain.[179]

There is weak evidence suggesting that

Viscosupplementation for osteoarthritis of the knee may have positive effects on pain and function at 5 to 13 weeks post-injection.[181]

Epidemiology

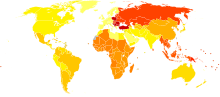

| no data ≤ 200 200–220 220–240 240–260 260–280 280–300 | 300–320 320–340 340–360 360–380 380–400 ≥ 400 |

Globally, as of 2010[update], approximately 250 million people had osteoarthritis of the knee (3.6% of the population).[183][184] Hip osteoarthritis affects about 0.85% of the population.[183]

As of 2004[update], osteoarthritis globally causes moderate to severe disability in 43.4 million people.[185] Together, knee and hip osteoarthritis had a ranking for disability globally of 11th among 291 disease conditions assessed.[183]

Middle East and North Africa (MENA)

In the Middle East and North Africa from 1990 to 2019, the prevalence of people with hip osteoarthritis increased three–fold over the three decades, a total of 1.28 million cases.[186] It increased 2.88-fold, from 6.16 million cases to 17.75 million, between 1990 and 2019 for knee osteoarthritis.[187] Hand osteoarthritis in MENA also increased 2.7-fold, from 1.6 million cases to 4.3 million from 1990 to 2019.[188]

United States

As of 2012[update], osteoarthritis affected 52.5 million people in the United States, approximately 50% of whom were 65 years or older.

In the United States, there were approximately 964,000 hospitalizations for osteoarthritis in 2011, a rate of 31 stays per 10,000 population.[191] With an aggregate cost of $14.8 billion ($15,400 per stay), it was the second-most expensive condition seen in US hospital stays in 2011. By payer, it was the second-most costly condition billed to Medicare and private insurance.[192][193]

Europe

In Europe, the number of individuals affected by osteoarthritis has increased from 27.9 million in 1990 to 50.8 million in 2019. Hand osteoarthritis was the second most prevalent type, affecting an estimated 12.5 million people. In 2019, Knee osteoarthritis was the 18th most common cause of years lived with disability (YLDs) in Europe, accounting for 1.28% of all YLDs. This has increased from 1.12% in 1990.[194]

India

In India, the number of individuals affected by osteoarthritis has increased from 23.46 million in 1990 to 62.35 million in 2019. Knee osteoarthritis was the most prevalent type of osteoarthritis, followed by hand osteoarthritis. In 2019, osteoarthritis was the 20th most common cause of years lived with disability (YLDs) in India, accounting for 1.48% of all YLDs, which increased from 1.25% and 23rd most common cause in 1990.[195]

History

Etymology

Osteoarthritis is derived from the

Other animals

Osteoarthritis has been reported in several species of animals all over the world, including marine animals and even some fossils; including but not limited to: cats, many rodents, cattle, deer, rabbits, sheep, camels, elephants, buffalo, hyena, lions, mules, pigs, tigers, kangaroos, dolphins, dugong, and horses.[198]

Osteoarthritis has been reported in fossils of the large carnivorous dinosaur Allosaurus fragilis.[199]

Research

Therapies

Pharmaceutical agents that will alter the natural history of disease progression by arresting joint structural change and ameliorating symptoms are termed as disease modifying therapy (DMOAD).[62] Therapies under investigation include the following:

- Strontium ranelate – may decrease degeneration in osteoarthritis and improve outcomes[200][201]

- Gene therapy – Gene transfer strategies aim to target the disease process rather than the symptoms.[202] Cell-mediated gene therapy is also being studied.[203][204] One version was approved in South Korea for the treatment of moderate knee osteoarthritis, but later revoked for the mislabeling and the false reporting of an ingredient used.[205][206] The drug was administered intra-articularly.[206]

Cause

As well as attempting to find disease-modifying agents for osteoarthritis, there is emerging evidence that a system-based approach is necessary to find the causes of osteoarthritis.[207]

Diagnostic biomarkers

Guidelines outlining requirements for inclusion of soluble biomarkers in osteoarthritis clinical trials were published in 2015,[208] but there are no validated biomarkers used clinically to detect osteoarthritis, as of 2021.[209][210]

A 2015 systematic review of biomarkers for osteoarthritis looking for molecules that could be used for risk assessments found 37 different biochemical markers of bone and cartilage turnover in 25 publications.[211] The strongest evidence was for urinary C-terminal telopeptide of type II collagen (uCTX-II) as a prognostic marker for knee osteoarthritis progression, and serum cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) levels as a prognostic marker for incidence of both knee and hip osteoarthritis. A review of biomarkers in hip osteoarthritis also found associations with uCTX-II.[212] Procollagen type II C-terminal propeptide (PIICP) levels reflect type II collagen synthesis in body and within joint fluid PIICP levels can be used as a prognostic marker for early osteoarthritis.[213]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x "Osteoarthritis". National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. April 2015. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 13 May 2015.

- ^ S2CID 208792655.

- ^ PMID 24462672.

- ^ PMID 27733282.

- ISBN 978-1-910315-16-3. Archivedfrom the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ "A National Public Health Agenda for Osteoarthritis 2020" (PDF). U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 27 July 2020.

- PMID 31034380.

- ^ a b c d e Vingård E, Englund M, Järvholm B, Svensson O, Stenström K, Brolund A, et al. (1 September 2016). Occupational Exposures and Osteoarthritis: A systematic review and assessment of medical, social and ethical aspects. SBU Assessments (Report). Graphic design by Anna Edling. Stockholm: Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services (SBU). p. 1. 253 (in Swedish). Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- PMID 23194896.

- ^ a b Conaghan P (2014). "Osteoarthritis – Care and management in adults". Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- PMID 25621213.

- ^ PMID 25481420.

- PMID 22230308.

- PMID 22124595.

- ^ "Swollen knee". Mayo Clinic. 2017. Archived from the original on 20 July 2017.

- ^ "Bunions: Symptoms and causes". Mayo Clinic. 8 November 2016. Archived from the original on 21 April 2017. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ^ S2CID 28990260.

- PMID 19752252.

- S2CID 21924096. Archived from the original(PDF) on 30 March 2023. Retrieved 15 July 2023.

- PMID 21383216.

- PMID 11360143.

- PMID 21481553.

- PMID 11033593.

- S2CID 24860734.

- ^ "Birth Defects: Condition Information". www.nichd.nih.gov. September 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2017.

- ^ "Congenital Disorders of Sexual Development". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- PMID 25837996.

- ^ "Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- ^ "Hereditary Hemochromatosis". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- ^ "Marfan Syndrome". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- ^ "Obesity". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- ^ "Arthritis, Infectious". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). 2009. Archived from the original on 21 February 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- PMID 21916390.

- PMID 34377550.

- ^ "Synovial Joints". OpenStax CNX. 25 April 2013. Archived from the original on 6 January 2016. Retrieved 14 October 2015.

- PMID 25182679.

- ^ S2CID 4214459.

- PMID 16695915.

- ^ PMID 6690447.

- PMID 18990590.

- PMID 2805680.

- PMID 1123375.

- ^ PMID 856064.

- S2CID 31367901.

- S2CID 7725467.

- PMID 24321104.

- PMID 11409127.

- S2CID 53091266.

- ISBN 978-0-19-991494-4.

- PMID 30725799. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- S2CID 12319076.

- PMID 12180735.

- ^ Osteoarthritis (OA): Joint Disorders at Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy Professional Edition

- ^ Phillips CR, Brasington RD (2010). "Osteoarthritis treatment update: Are NSAIDs still in the picture?". Journal of Musculoskeletal Medicine. 27 (2). Archived from the original on 12 February 2010. Retrieved 9 February 2010.

- ^ Kalunian KC (2013). "Patient information: Osteoarthritis symptoms and diagnosis (Beyond the Basics)". UpToDate. Archived from the original on 22 September 2010. Retrieved 15 February 2013.

- PMID 2242058.

- PMID 16432092.

- ^ "Tönnis Classification of Osteoarthritis by Radiographic Changes". Society of Preventive Hip Surgery. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- PMID 15454130.

- ^

- ^ PMID 30801133.

- ^ S2CID 53284022.

- ^ PMID 19352008.

- S2CID 85493753.

- S2CID 251782088.

- S2CID 246314113.

- ^ PMID 19207981.

- PMID 30961569.

- PMID 36233208.

- PMID 23253613.

- PMID 24756895.

- ^ PMID 29664187.

- ^ S2CID 24620456.

- S2CID 17423569.

- PMID 20091582.

- ^ PMID 27594189.

- PMID 21146444.

- S2CID 19135129.

- PMID 15517643.

- PMID 24785984.

- PMID 28141914.

- PMID 34916210.

- S2CID 20664287.

- PMID 23989797.

- ^ S2CID 35262399.

- S2CID 41951368.

- ^ "Osteoarthritis Lifestyle and home remedies". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 25 January 2016.

- PMID 27007113.

- S2CID 205173688.

- PMID 24923633.

- PMID 27007113.

- ^ PMID 14584019.

- ^ a b c d "Pain Relief with NSAID Medications". Consumer Reports. January 2016. Archived from the original on 21 April 2019. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- ^ PMID 17719803.

- PMID 25828856.

- PMID 18405470.

- S2CID 207482912.

- PMID 25879879.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2024 (link - PMID 28530031.

- ^ PMID 27103611.

- PMID 15654705.

- PMID 27036633.

- S2CID 11711160.

- ^ S2CID 205168274.

- ^ PMID 31132298.

- ^ PMID 23152242.

- S2CID 53080408.

- ^ PMID 21169345.

- S2CID 43530618.

- S2CID 20975564.

- PMID 30961569.

- S2CID 207946424.

- PMID 36559005.

- PMID 15039276.

- PMID 26490760.

- PMID 26674652.

- PMID 28510679.

- PMID 29533245.

- ^ S2CID 5660398.

- PMID 26677239.

- PMID 26475434.

It is unclear if there is a benefit or harm for HA as treatment for ankle OA

- PMID 34671820.

- PMID 24286802.

- PMID 25207275.

- PMID 24782334.

- S2CID 221770606.

- PMID 19057730.

- S2CID 28484710.

- PMID 23307684.

- PMID 23218429.

- PMID 28351833.

- PMID 25609443.

- S2CID 27864530.

- PMID 20927773.

- ^ "Osteochondral Autograft & Allograft". Washington University Orthopedics. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- PMID 25969934.

- PMID 25534362.

- PMID 28244303.

- ^ PMID 33055541.

- ^ PMID 32315453.

- PMID 25503775.

- ^ PMID 31322289.

- PMID 24387819.

- PMID 24792949.

- PMID 26080045.

- PMID 22925619.

- PMID 20847017.

- S2CID 24251411.

- from the original on 10 March 2013.

- PMID 21220090.

The best current evidence suggests that the effect of these supplements, alone or in combination, on OA pain, function, and radiographic change is marginal at best.

- PMID 22850875.

- PMID 25050057.

- PMID 18279766.

- ^ PMID 22293240.

- PMID 24953861.

- PMID 19111223.

- PMID 25629804.

- ^ PMID 24848732.

- PMID 25621100.

- ^ "Piascledine" (PDF). Haute Autorité de santé. 25 July 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 December 2016.

- S2CID 231724282.

- PMID 19821403.

- PMID 33882635.

- PMID 36224305.

- PMID 26818459.

- S2CID 23994681.

- PMID 27655986.

- PMID 20091527.

- PMID 29729027.

- (PDF) from the original on 27 December 2016.

- PMID 19821296.

- |intentional=yes}}.)

- PMID 17587446.

- PMID 17943920.

- ^ PMID 14584019.

- PMID 20091539.

- S2CID 199452082.

- PMID 21959097.

- PMID 24338431.

- PMID 16625635.

- ^ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. Archived from the original on 11 November 2009. Retrieved 11 November 2009.

- ^ S2CID 37565913.

- PMID 23245607.

- ISBN 978-92-4-156371-0.

- S2CID 251912479.

- S2CID 257911199.

- S2CID 256385406.

- ^ a b "Arthritis-Related Statistics: Prevalence of Arthritis in the United States". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 9 November 2016. Archived from the original on 29 December 2016.

- PMID 11464731.

- ^ Pfuntner A., Wier L.M., Stocks C. Most Frequent Conditions in U.S. Hospitals, 2011. HCUP Statistical Brief #162. September 2013. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, Maryland."Most Frequent Conditions in U.S. Hospitals, 2011 #162". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ Torio CM, Andrews RM (August 2013). "National Inpatient Hospital Costs: The Most Expensive Conditions by Payer, 2011". Rockville, Maryland: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Archived from the original on 14 March 2017.

- PMID 24455786.

- ^ "PEMFs and knee osteoarthritis - almagia". 8 November 2017. Retrieved 18 August 2023.

- PMID 35598766.

- ISBN 978-81-89093-74-7.

- ISSN 2331-2270.

- PMID 28542897.

- ISBN 978-0-253-33907-2.

- ISBN 978-1-118-43767-4. Archivedfrom the original on 31 December 2013.

- PMID 19087296.

- PMID 11195326.

- S2CID 24727257.

- PMID 26601056.

- ^ "Seoul revokes license for gene therapy drug Invossa". Yonhap News Agency. 28 May 2019.

- ^ a b "Korea OKs first cell gene therapy 'Invossa'". The Korea Herald. 12 July 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2017.

- PMID 25639920.

- PMID 25952342.

- ISBN 978-0-323-90597-8.

- PMID 34359288.

- PMID 25963100.

- PMID 25623593.

- PMID 28287489.

External links

- "Osteoarthritis". MedlinePlus. U.S. National Library of Medicine.