Ostsiedlung

| History of Germany |

|---|

|

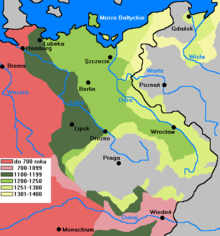

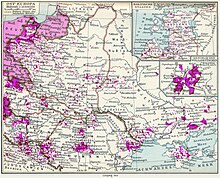

Ostsiedlung (German pronunciation: [ˈɔstˌziːdlʊŋ], literally "East settlement") is the term for the Early Medieval and High Medieval migration of ethnic Germans and Germanization of the areas populated by Slavic, Baltic and Finnic peoples, the most settled area was known as Germania Slavica. Germanization efforts included eastern parts of Francia, East Francia, and the Holy Roman Empire and beyond; and the consequences for settlement development and social structures in the areas of settlement. Other regions were also settled, though not as heavily. The Ostsiedlung encompassed multiple modern and historical regions such as Germany east of the Saale and Elbe rivers, the states of Lower Austria and Styria in Austria, Livonia, Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia, Hungary, and Transylvania in Romania.[1][2]

The majority of Ostsiedlung settlers moved individually, in independent efforts, in multiple stages and on different routes. Many settlers were encouraged and invited by the local princes and regional lords,[3][4][5] who sometimes even expelled part of the indigenous populations to make room for German settlers.[a]

Smaller groups of migrants first moved to the east during the early Middle Ages. Larger treks of settlers, which included scholars, monks, missionaries, craftsmen and artisans, often invited, in numbers unverifiable, first moved eastwards during the mid-12th century. The military territorial conquests and punitive expeditions of the Ottonian and Salian emperors during the 11th and 12th centuries do not form part of the Ostsiedlung, as these actions didn't result in any noteworthy settlement establishment east of the Elbe and Saale rivers. The Ostsiedlung is considered to have been a purely Medieval event as it ended in the beginning of the 14th century. The legal, cultural, linguistic, religious and economic changes caused by the movement had a profound influence on the history of Eastern Central Europe between the Baltic Sea and the Carpathians until the 20th century.[7][8][9]

In the 20th century, accounts of the Ostsiedlung were heavily exploited by

In and after World War II (1944–1950), Germans were driven out and deported to rump Germany from the East and their language and culture were lost in most areas (including the German-dominated lands which Germany lost after this war) in which German people had settled during the Ostsiedlung; except part of Eastern Austria and especially Eastern Germany.

Early medieval Central Europe

During the 4th and 5th centuries, in what is known as the Migration Period, Germanic peoples seized control of the decaying Western Roman Empire in the South and established new kingdoms within it. Meanwhile, formerly Germanic areas in Eastern Europe and present-day Eastern Germany, were settled by Slavs.[14]

Under Carolingian rule

- the

- the Saxon Eastern March or Nordalbingen March between the Eider and Elbe in what is now Holstein against the Obotrites

- the Thuringian or Sorbian March on the Saale, against the Sorbs dwelling behind the limes sorabicus

- the Franconian march in what is now Upper Franconia, against the Czechs

- the Avar March between the Enns and the Vienna Woods (the later Austrian March), against the Avars[18]

- the March of Pannonia east of Vienna (divided into Upper and Lower)

- the Carantanian march

- the Friulian march

This was the earliest recorded and planned "eastern policy" under Charlemagne, who wanted to protect the eastern border of the Frankish Empire, and also wanted to solidify his position in the east by declaring war on the

The tribes that populated these marches were generally unreliable allies of the Empire, and successor kings led numerous, yet not always successful, military campaigns to maintain their authority.

In 843 the Carolingian Empire was partitioned into three independent kingdoms as a result of dissent among Charlemagne's three grandsons over the continuation of the custom of partible inheritance or the introduction of primogeniture.[20]

East Francia and Holy Roman Empire

Under the rule of King

).In a series of punitive actions, large territories in the northeast between the

Slavic revolt of 983

In 983, the

Eastern marches of East Francia and Holy Roman Empire

The territories (from north to south):

- the Schleswig

- Marca Geronis (march of Gero), a precursor of the Saxon Eastern March, later divided into smaller marches (the Northern March, which later was reestablished as Margraviate of Brandenburg; the March of Lusatia and the Margravate of Meissen in what is now Saxony; the March of Zeitz; the March of Merseburg; the Milzener March around Bautzen)

- Austrian March (marcha Orientalis, the "Eastern March" or "Bavarian Eastern March" (German: Ostmark) in what is now lower Austria)

- the Carantania or March of Styria

- the Drau March (Maribor and Ptuj)

- the Sann March (Celje)

- the Krain or Carniola march, also Windic March and White Carniola (White March), in what is now Slovenia

Eastern Saxon Marches

The

The Margravate of Meissen and Transylvania were populated by German settlers, beginning in the 12th century. From the end of the 12th century onwards, monasteries and cities were established in Pomerania, Brandenburg, Silesia, Bohemia, Moravia and eastern Austria. In the Baltics, the Teutonic Order founded a crusader state in the beginning of the 13th century.[27][9]

Northeastern Germany and Holstein

Background

A call for a crusade against the Wends in 1108, probably coming from a Flemish clerk in the circles of the archbishop of Magdeburg, which included the prospect of profitable land gains for new settlers, had no noticeable effect and resulted in neither a military campaign nor a movement of settlers into the area.[28][29]

Although the first settlers had already arrived in 1124, being mostly of Flemish and Dutch origin, they settled south of the Eider river, followed by the conquest of the land of the Wagri in 1139, the founding of Lübeck in 1143 and the call by Count Adolf II of Schauenburg to settle in Eastern Holstein, and Pomerania in the same year.[30][31]

Weakened by ongoing internal conflicts and constant warfare, the independent Wendish territories finally lost the capacity to provide effective military resistance. From 1119 to 1123, Pomerania invaded and subdued the northeastern parts of the Lutici lands. In 1124 and 1128, Wartislaw I, Duke of Pomerania, at that time a vassal of Poland, invited bishop Otto of Bamberg to Christianize the Pomeranians and Liutizians of his duchy.[32][33] In 1147, as a campaign of the Northern Crusades, the Wendish Crusade was mounted in the Duchy of Saxony to retake the marches lost in 983. The crusaders also headed for Pomeranian Demmin and Szczecin (Stettin), despite these areas having already been successfully Christianized. The Crusade caused widespread devastation and slaughter.[34]

Settlement

This created ideal conditions for German settlement, some of the most prominent supporters of settlement included

After the Wendish crusade, Albert the Bear was able to establish and expand the Margraviate of Brandenburg in 1157 on approximately the territory of the former Northern March, which since 983 had been controlled by the Hevelli and Lutici tribes. The Bishopric of Havelberg, that had been occupied by revolting Lutici tribes was reestablished to Christianize the Wends.[36]

In 1164, after Saxon duke

Bohemia

Background

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2024) |

German influence in Bohemia began when Duke

Settlement

All of this laid the perfect conditions for German settlement and dominance of Bohemia [

End

Eventually, during the late 14th and early 15th centuries' settlement slowed down, due to numerous factors such as the Black Plague in Germany, and the Hussite Wars.[45]

Prussia and the Baltics

The Teutonic State was formed in the aftermath of the

The Teutonic State established a comprehensive administrative structure, and modernized the old traditional tribal structure of the region. An integral part of the Order other than converting

Hungary

While Hungary was never conquered by the Holy Roman Empire and was never in focus of German settlement, it still had a sizeable German population. During the 11th century,

When Stephen I married Gisela of Bavaria, many German knights came to Hungary, joining its military. They were often rewarded with large estates and entry into the nobility.[52] In 1224, Andrew II signed a charter laying out the duties and rights of the Germans in the kingdom. The king defined their duties such as the payment of tax, military service, and housing of the king and his officials. In exchange, they were able to elect their priests and officials independently and their merchants were exempt from customs duties. Their markets were also not taxed. No outsider was allowed to receive villages or estates in German land where only the monarch and the Count of Hermannstadt had jurisdiction.[53]

Social and demographic background

Political and military events were greatly influenced by a massive population increase throughout Europe in the High Middle Ages. From the 11th to the 13th centuries, the population in the kingdom of Germany increased from about four to twelve million inhabitants.[54][55] During this time, the High Medieval Landesausbau (inland settlement) took place, when arable land was largely expanded at the expense of forested areas. Although new land was won and numerous settlements created, demands could not be absorbed.[56] Another factor was a surplus of offspring of the nobility who were not entitled to inheritance, but after the success of the first crusade, took their chances of acquiring new lands in the peripheral regions of the Empire.[9][57]

There is no doubt that there were "rather numerous German settlers" in Eastern Central who were responsible for bringing German law in the earliest stages of the colonization. Other settlers included Walloons, Jews, Dutch, Flemish, and later Poles, especially in the territory of modern Ukraine.[58]

The migration of the

Technical and agricultural development

The Medieval Warm Period, which began in the 11th century resulted in higher average temperatures in Central Europe. Additional technical progress in agriculture, for example through the construction of mills, Three-field farming and increased cultivation of grain (graining) led to general population increase.

The new settlers not only brought their customs and language with them, but also new technical skills and equipment that were adapted within a few decades, especially in agriculture and crafts.[60] These included:

The amount of cultivated land increased as large forested areas were cleared. The extent of land increase differed by region. In Silesia it had doubled (16% of the total area) by the beginning of the 11th century, 30% in the 16th century and the highest increase rates in the 14th century, the total area of arable land increased seven – to twentyfold in many Silesian regions during the Ostsiedlung.

Parallel to agricultural innovations new forms of farm layout and settlement structuring (division and classification of land) were introduced. Farmland was divided into Hufen, (English hides) and larger villages replaced the previously dominant type of small villages consisting of four to eight farms as a complete transformation of the previous settlement structure occurred. The cultural landscape of East Central Europe formed by the medieval settlement processes essentially prevails until today.

Dutch settlers and hydraulic engineering

Flemish and Dutch settlers were among the first to immigrate to Mecklenburg at the beginning of the 12th century. In the following years, they moved further east to Pomerania and Silesia and in the south to Hungary, motivated by the lack of settlement areas in their already largely developed home areas and several flood disasters and famines.[61]

Experienced and skilled hydraulic engineers, they were in high demand at the settlements of the as yet undeveloped areas east of the Elbe. The land was drained by creating a network-like structure of smaller drainage ditches that drained the water in main ditches. Roads connecting the settlers' individual farms ran along these main trenches.

Dutch settlers were recruited by the local rulers in large numbers, especially during the second half of the 12th century. In 1159/60, for example, Albert the Bear granted Dutch settlers the right to take possession of former Slavic settlements. The preacher Helmold of Bosau reported on this in his Slavic chronicle: "Finally, when the Slavs were gradually dispersing, he (Albrecht) sent to Utrecht and the Rhine region, and also to those who live by the ocean, who under the power of the sea had suffered, the Dutch, Zealanders and Flemings, where he attracted a lot of people and let them live in the castles and villages of the Slavs."[61]

Agricultural implements

The Slavs used ploughs and agricultural implements before the arrival of German settlers. The oldest meaningful reference to this can be found in a Slavic chronicle, in which the use of a plough as an areal measurement is mentioned. Although heavier and useful ploughs were brought by the settlers.[b][63]

In the 12th and 13th century documents, the Ard without a mouldboard is mentioned. It tear opens the soil and spreads the soil to both sides without turning it. It is therefore particularly suitable for light and sandy subsoil. In the mid 13th century, the Three-field system was introduced east of the Elbe. This new cultivation method required the use of the heavy mouldboard plough that digs up the earth deeply and turns it around in a single operation.[c]

The different modes of operation of the two devices also had an impact on the shape and size of the cultivation areas. The fields worked with the ard had about the same field length and width and a square base. Long fields with a rectangular base were much more suitable for the mouldboard plough, as the heavy implements had to be turned less often. Planting and cultivation of oats and rye was promoted, and soon these cereals became the most important type of grain. Farmers who used mouldboard ploughs were required to pay double tax fees.[64]

Pottery

Potters were among the first group of artisans who also settled in the rural areas. Typical Slavic ceramics were the Flat-bottom vessels. With the influx of western settlers, new vessel shapes such as the rounded jar were introduced, inclusive hard-fired processes, that improved ceramics quality. This type of ceramics, known as Hard Grayware, became widespread east of the Elbe by the end of the 12th century. It was manufactured extensively in Pomerania by the 13th century, when more advanced manufacturing methods, such as the tunnel kiln, enabled the mass production of ceramic household goods. The demand for household goods such as pots, jugs, jugs and bowls, which had previously been made of wood, increased steadily and promoted the development of new sales markets.

During the 13th century, glazed ceramics were introduced and the import of stoneware increased. The transfer of technology and knowledge affected the way of life of old and new settlers in a variety of ways and, in addition to innovations in agriculture and handicrafts, also included other areas, such as weapons technology, documents and coins.[65]

Architecture

The Slavic population (Sorbs), who lived east of the Elbe, primarily built log houses, which had proven suitable for the regional climates and wood was plentiful in the continental regions. The German settlers, mainly from Franconia and Thuringia, who advanced into the area in the 13th century, brought with them the half-timbering style, which was already known to the Germanic peoples, as a wood-saving, solid and stable construction method, that allowed multi-storey buildings. A combination of the two construction methods was difficult because the horizontally stacked wood of the log room expands differently in height than the vertical posts of the framework. The result was the new type of half-timbered house with a timber frame around the ground floor block, capable to support a second floor, which was made of half-timber.

Population and settlement

The Ostsiedlung followed an immediate rapid population growth throughout Central and Eastern Europe. During the 12th and 13th centuries, the population density increased considerably. The increase was due to the influx of settlers on the one hand and an increase in slavic populations after the settlement on the other hand. Settlement was the primary reason for the increase e.g. in the areas east of the Oder, the Duchy of Pomerania, western Greater Poland, Silesia, Austria, Moravia, Prussia and Transylvania, while in the larger part of Central and Eastern Europe indigenous populations were responsible for the growth. Author Piskorski wrote that "insofar as it is possible to draw conclusions from the less than rich medieval source material, it appears that at least in some East Central European territories the population increased significantly. It is however possible to contest to what extent this was a direct result of migration and how far it was due to increased agricultural productivity and the gathering pace of urbanization."[66] In contrast to Western Europe, this increased population was largely spared by the 14th-century Black Death pandemic.[67]

With the German settlers new systems of

Urban development and city foundations

The development of

The towns established during the Ostsiedlung were Free Towns (civitates liberae) or called "New Towns" by its contemporaries. The rapid increase in the number of towns led to an "urbanization of East Central Europe". The new towns differed from their predecessors in:

- The introduction of

- The introduction of permanent markets. As previously, markets were held only periodically, townspeople were now free to trade and marketplaces became a central feature of the new towns.[74]

- Layout: The new towns were planned towns as their layout was usually rectangular.[69]

City laws and grants

The granting of city rights played an important role in attracting German settlers.[75] The town charter privileged the new residents and existing suburban settlements with a market were given formal town charter and then rebuilt or expanded. Even small settlements inhabited by native people would eventually be granted these new rights. Regardless of existing suburban settlements, locators were commissioned to establish completely new cities, as the goal was to attract as many people as possible in order to create new, flourishing population centers.[76][77]

Expansion of the German city laws

Among the many different German city laws, the

Religious changes

The pagan Wends had been the target of Christianization attempts before the beginning of the Ostsiedlung, since the government of emperor Otto I and the establishment of dioceses east of the Elbe. The Slav uprising of 983 put an end to these efforts for almost 200 years. In contrast to the Czechs and Poles who had been Christianized before the turn of the millennium, the conversion attempts of the Elbe Slavs initially accompanied by violence. The arrival of new settlers from around 1150 on led to a civil Christianization of the areas between the Elbe and Oder. The new settlers first built wooden and later field stone parish churches in their villages. Some places of worship, such as the St. Mary in Brandenburg, and the Lehnin Abbey, were built on pagan shrines. The Cistercians, who had been assigned a prominent role by church authorities, combined the spread of faith and settlement development. Their monasteries with extensive international connections played a vital role in the development of the communities.[78]

Settlers

The majority of the settlers were Germans of the Holy Roman Empire. Significant numbers of Dutch settlers participated, particularly in the early 12th century in the area surrounding the Middle Elbe River.[79] To a lesser extent Danes, Scots or local Wends and (French-speaking) Walloons participated as well. Among the settlers were landless children of noble families who could not inherit property.[80]

Besides the marches, adjacent to the Empire, Germans settled in areas farther east, such as the Carpathians, Transylvania, and along the Gulf of Riga. Settlers were invited by local secular rulers, such as dukes, counts, margraves, princes and (only in a few cases due to the weakening central power) the king. The sovereigns in East Central Europe owned large territories, of which only small portions were arable, which generated very little income.[57] The lords offered considerable privileges to new settlers from the Empire. Starting in the border marks, the princes invited people from the Empire by granting them land ownership and improved legal status, binding duties and the inheritance of the farm. The landowners eventually benefited from these rather generous conditions for the farmers, and generated income from the land that had previously been fallow.[80]

Most sovereigns transferred the specific recruitment of settlers, the distribution of the land and the establishment of the settlements to so-called Lokators (allocator of land). These men, who usually came from the lower nobility or the urban bourgeoisie, organized the settlement trains, that included advertising, equipment and transport, land clearing and preparation of the settlements. Locator contracts settled rights and obligations of the locators and the new settlers.[71][81]

Towns were founded and granted German town law. The agricultural, legal, administrative, and technical methods of the immigrants, as well as their successful Christianization of the native inhabitants, led to a gradual transformation of the settlement areas, as Slavic communities adopted German culture.[citation needed] German cultural and linguistic influence lasted in some of these areas right up to the present day.[1]

In the mid 14th century, the migration process slowed considerably as a result of the Black Death. The population probably decreased by that time and economically marginal settlements were left, in particular at the coast of Pomerania and Western Prussia. Only a century later, local Slavic leaders of Pomerania, Western Prussia and Silesia invited German settlers again.[82]

Assimilation

Settlement was the pretext for assimilation processes that lasted centuries. Assimilation occurred in both directions – depending on the region and the majority population, Slavic and German settlers mutually assimilated each other.

Germans

The Polonization process of German settlers in Kraków and Poznań lasted about two centuries. The community could only continue its isolated position with a continuation of newcomers from German lands. The Sorbs also assimilated German settlers, yet at the same time, small Sorbic communities were themselves assimilated by the surrounding German-speaking population. Many Central and Eastern European towns developed into multi-ethnic melting pots.[83]

Treatment, involvement and traces of the Wends

Although Slavic population density was generally not very high compared to the Empire and had, as a result of the extensive warfare during the 10th to 12th centuries, even further declined, some settlement centers maintained their Wendish populations to varying degrees, resisting assimilation for a long time.[83]

In the territories of Pomerania and Silesia, German migrants did not settle in the old Wendish villages and set up new ones on grounds allotted to them by the Slavic nobility and the monastic clergy. In the marches west of the Oder, the Wends were occasionally driven out and the villages rebuilt by settlers. The new villages would nevertheless keep their former Slavic names. In the case of the village Böbelin in Mecklenburg, the evicted Wendish inhabitants repeatedly invaded their former village, hindering a resettlement.[84]

In the Sorbian March the situation was again different as the area and in particular Upper Lusatia is situated close to Bohemia, ruled by a Slavic dynasty, a loyal and powerful duchy of the Empire. In this environment, German feudal lords often cooperated with the Slavic inhabitants. Wiprecht of Groitzsch, a prominent figure during the early German migration period only acquired local power through the marriage to a Slavic noblewoman and the support of the Bohemian king. German-Slavic relations were generally good, while relations between Slavic-governed Bohemia and Slavic-governed Poland were marred by constant struggle.

Discrimination against the Wends was not a part of the general concept of the Ostsiedlung. Rather, the Wends were subject to a low taxation mode and thus not as profitable as new settlers. Even though the majority of the settlers were Germans (

Most of the Wends were gradually assimilated. However, in isolated rural areas where Wends constituted a substantial part of the population, they continued their culture. These were the

. Lusatia was inhabited by a large population of Sorbs until the end of the 19th century as linguistic assimilation occurred in a relatively short time.Language exchange

The Ostsiedlung caused the adoption of loan words, foreign words and loan translations among the German and the Slavic languages. Direct contact between Germans and Slavs caused direct language exchange of language elements due to the bilingualism of people or the spatial proximity of the speakers of the respective language. Remote contact took place during trade travels or political embassies.[85][86]

The oldest adoption of naming units dates back to

| Category | English | German | Polish | Czech | Slovakian | Hungarian |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Administration | mayor | Bürgermeister | burmistrz | purkmistr | richtár / burgmajster | polgármester |

| Administration | margrave | Markgraf | margrabia | markrabě | markgróf | őrgróf |

| Craft | brick | Ziegel | cegła | cihla | tehla | tégla |

| Food | pretzel | Brezel | precel | preclík | praclík | perec |

| Food | oil | Öl | olej | olej | olej | olaj |

| Agriculture | mill | Mühle | młyn | mlýn | mlyn | malom (mahlen) |

| Trade | (cart-)load | Fuhre | fura | fůra | fúra | furik |

| Others | flute | Flöte | flet | flétna | flauta | flóta |

Names of localities and settlements

As Slavic and Wendish locality names were widely adopted, they represent, in adapted and further developed form, a very high proportion of East German toponyms and place names. These are recognizable at word endings, such as -ow (Germanized -au, as in Spandau), -vitz or -witz and sometimes -in. Newly created villages were given German names that ended, for example, with -dorf or -hagen in the North, and -rode or -hain in the South. The name of the settler's place of origin (example: Lichtervelde in Flanders) could also become part of the place name. If a German settlement was founded alongside a Wendish settlement, the name of the Wendendorf could also be adopted for the German village, the distinction was then made through additions (for example: Klein- or Wendisch- / Windisch- for Wendendorf, Groß- or Deutsch- for German).[74][89]

In German-speaking areas most inherited

The former ethnic variety of German (Deutsch-) and Slavic (Wendisch-, Böhmisch-, Polnisch-) toponyms was discontinued by the Eastern European republics after World War II. Villages and towns were renamed in Slavic only. Memory of the history of German settlement was no longer appreciated.[citation needed]

Family Names

It's estimated that approximately 25% of all German family names are of Slavic origin,[90][91] most of these are Polish.

| Name | Origin and meaning |

|---|---|

| Nowak | Slavic, now-/nov- ‘new’ (German: Neu) + -ak means "New settlers" (German: Neuansiedler |

| Noack | Sorbian, nowy ‘new’ (German: Neu) + -ak means "New settlers" (German: Neuansiedler) |

| Kretschmer | Czech, krčmář means "Publican" |

| Mielke | Slavic, nickname with mil- "love, dear" (German: Lieb, Teuer) + -ek |

| Stenzel | Polish nickname Stanisław |

| Kaminski | Polish, settlement name- kamień "Stone" (German: Stein) + -ski |

| Wieczorek | Polish, wieczor "evening" (German: Abend) + -ek |

| Kowalski | Polish, settlement name or kowal "Blacksmith" (German: Schmied) + -ski |

| Grabowski | Polish, settlement name + -ski |

| Jankowski | Polish, settlement or the nickname Janek + -owski |

End of migration

There is no clear cause nor a definite end point in time of the Ostsiedlung. However, a slowdown in the settlement movement can be observed after the year 1300 and in the 14th century only a few new settlements with the participation of German-speaking settlers were founded. An explanation for the end of the Ostsiedlung must include various factors without being able to clearly weigh or differentiate between them. The deterioration of the climate from around 1300 as the beginning of the "Little Ice Age", the agricultural crisis that began in the mid 14th century. In the wake of the demographic slump caused by the 1347 Plague, profound devastation processes have taken place. If a clear connection could be established here, the end of the Ostsiedlung would be understood as part of the crisis of the 14th century.[93]

Drang nach Osten

In the 19th century, recognition of this complex phenomenon coupled with the rise of nationalism. This led to a largely unhistoric ethnically inspired nationalist reinterpretation of the medieval process. In Germany and some Slavic countries, most notably Poland, the Ostsiedlung was perceived in nationalist circles as a prelude to contemporary expansionism and Germanization efforts, the slogan used for this perception was Drang nach Osten (Drive or Push to the East).[94][95]

The German settlement processes in Pomerania did not follow any kind of ideology, nor did the other migratory movements. Rather, the German settlement in Pomerania was shaped exclusively by practical requirements...The national historiography that established itself around the middle of the 19th century retrospectively constructed a Slavic-Germanic contrast in the Ostsiedlung process of the High Middle Ages. However, that was the ideology of the 19th century, not the Middle Ages...Settlement was to be "cuiuscunque gentis et cuiuscunque artis homines" ('people of whatever origin and whatever craft') which was recorded in numerous documents issued by Pomeranian dukes and Rügish princes. -Buchholz[96]

Legacy

The 20th century wars and nationalist policies severely altered the ethnic and cultural composition of Central and Eastern Europe. After

Room for them was made during World War II, in line with the Generalplan Ost by expulsion of Poles and enslaving these and other Slavs according to the Nazi's Lebensraum concept. In order to press the territorial claims of Germany and to demonstrate supposed German superiority over non-Germanic peoples, whose cultural, urban and scientific achievements in that era were undermined, rejected, or presented as German.[11][12][13] While further realization of this mega plan, aiming at a total reconstitution of Central and Eastern Europe as a German colony, was prevented by the war's turn, the beginning of the expulsion of 2 million Poles and settlement of Volksdeutsche in the annexed territories yet was implied by 1944.[97]

The

The Medieval settlers areas, that constituted the Eastern provinces of the modern

See also

- Cultural assimilation

- German diaspora

- Zipser Willkür

- Transylvanian Saxon University

- Drang nach Osten

- Limes Saxoniae

- Barbarian invasions

- Wends

- Wendish Crusade

- Northern Crusades

- Medieval demography

- German exonyms

- Germanization

- Germanization of Poles during Partitions

- History of Germans in Russia and the Soviet Union

- Historical migration

- Josephine colonization

- Population transfer in the Soviet Union

- Polonization

- Pre-modern human migration

Notes

- ^ "The German settlement was preceded in some areas by military conquest and the ejection of the indigenous population. Elsewhere, however, it was the native princes who invited in settlers and even expelled part of the indigenous population to make way for the newcomers."[6]

- ^ "The Slavonic peoples of Central and Eastern Europe were not ignorant of agriculture, as is sometimes maintained. The Germans, however, plainly understood the principles of cereal exploitation and they probably also introduced to the regions of settlement the 'heavy' plough or Pflug and the system of annual three-field rotation."[62]

- ^ "The Slavonic peoples of Central and Eastern Europe were not ignorant of agriculture, as is sometimes maintained. The Germans, however, plainly understood the principles of cereal exploitation and they probably also introduced to the regions of settlement the 'heavy' plough or Pflug and the system of annual three-field rotation."[62]

References

- ^ ISBN 978-1-351-88483-9.

- ISBN 978-1-351-89008-3.

- ISBN 978-0-19-960516-3.

- ISBN 978-3-640-04806-9. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ Szabo 2008, p. 9.

- ^ Palgrave Macmillan UK 1999, p. 11.

- ^ Bartlett 1998, p. 14.

- ^ Szabo 2008, p. 10.

- ^ a b c d Katalin Szende. "Iure Theutonico ? German settlers and legal frameworks for immigration to Hungary in an East-Central European perspective". Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ "The Slippery Memory of Men": The Place of Pomerania in the Medieval Kingdom of Poland (East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450), by Paul Milliman. Brill: Leiden, 2013, page 2 – "There is a huge literature on this topic in Polish and German, which was until recently lumped together with a whole host of other topics (including the peaceful settlement in East Central Europe of Germans and other western Europeans, who had been invited by Slavic lords) as the Drang nach Osten. Because of this term's associations with nineteenth-century nationalism and twentieth-century Nazism, it has for the most part been scrapped, only to be replaced by the deceptively benign 'Ostsiedlung' or the even more problematical 'Ostkolonisation[...]' [...]."

- ^ a b The Slippery Memory of Men (East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450) by Paul Milliman page 2.

- ^ a b Jan M. Piskorski: "The historiography of the so-called 'east colonisation' and the current state of research" in: The Man of Many Devices, Who Wandered Full Many Ways ...: Festschrift in Honor of Janos M.Bak [Hardcover] Balázs Nagy (Editor), Marcell Sebok (Editor) page 654, 655.

- ^ a b The Holocaust as Colonial Genocide: Hitler's 'Indian Wars' in the 'Wild East' – page 38; Carroll P. Kakel III – 2013: "Within National Socialist discourse, the Nazis purposefully and skillfully presented their eastern colonization project as a 'continuation of medieval Ostkolonisation [eastern colonization], celebrated in the language of continuity, legacy, and colonial grandeur".

- ^ Minahan 2000, pp. 288–289.

- ISBN 978-0-674-73739-6.

- ISBN 978-0-7864-6027-4.

- ISBN 978-1-134-78669-5.

- ISBN 978-0-7546-0011-4.

- ISBN 978-1-55753-443-9.

- ^ Jenny Benham. "Treaty of Verdun (843)". Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- ^ Schulman 2002, pp. 325–27.

- ISBN 978-0-15-505552-0.

- ISBN 978-1-317-87238-2.

- ISBN 978-0-7864-9714-0.

- ^ Wolfgang H. Fritze (1984). Der slawische Aufstand von 983: eine Schicksalswende in der Geschichte Mitteleuropas.

- ^ "The Medieval Elbe – Slavs and Germans on the Frontier". University of Oregon. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- ^ James Westfall Thompson (1962). Feudal Germany. F. Ungar Publishing Company.

- ISBN 978-90-04-15502-2.

- ISBN 978-90-04-39519-0.

- ISBN 978-0-415-19073-2.

- ISBN 978-90-04-22646-3.

- ISBN 978-1-60206-535-2.

- ^ Thomas Kantzow (1816). Pomerania, oder, Ursprunck, Altheit und Geschicht der Völcker und Lande Pomern, Cassuben, Wenden, Stettin, Rhügen in vierzehn Büchern. Auf Kosten des Herausgebers, in Commission bey E. Mauritins. pp. 1–.

- ISBN 978-0-393-30153-3. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ISBN 978-0-393-30153-3. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Henryk Bagiński (1946). Poland and the Baltic: The Problem of Poland's Access to the Sea. Polish Institute for Overseas Problems.

- ISBN 978-0-521-31980-5.

- JSTOR 4201997– via JSTOR.

- ^ Mahoney, William (2011). The History of the Czech Republic and Slovakia. ABC-CLIO. p. 42.

- ^ Krofta, Kamil (1957). "Bohemia to the Extinction of the Premyslids". In Tanner, J.R.; Previte-Orton, C.W.; Brooke, Z.N. (eds.). Cambridge Medieval History:Victory of the Papacy. Vol. VI. Cambridge University Press. p. 426.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4094-2245-7.

- ISBN 978-1-4094-2245-7.

- ISBN 978-1-4094-2245-7.

- S2CID 146531995– via Cambridge University Press.

- ISBN 978-1-315-23978-1.

- ^ Bilmanis, Alfreds (1944). Latvian-Russian relations: documents. The Latvian legation.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles George (1907). The Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Bilmanis, Alfreds (1945). The Church in Latvia. Drauga vēsts.

- ISSN 2034-9416.

- ISBN 978-1-136-16281-7. Retrieved 14 July 2023.

- S2CID 232081010.

- ^ Szende 2019, p. 362.

- ISBN 9781315239781.

- ISBN 978-90-420-2831-9.

- ISBN 978-0-521-54071-1.

- ISBN 978-3-486-55024-5.

- ^ a b Bartlett 1998, p. 147.

- ^ The Germans and the East, Charles W. Ingrao, Franz A. J. Szabo, Jan Piskorski Medieval Colonization in Europe, pages 31-32, Purdue University Press, 2007 "The sources leave no doubt that rather numerous German settlers arrived into many areas of East Central Europe and that particularly in the earliest period of eastern colonization the so-called German law was introduced above all by immigrants from the German lands. This particularly affected the territory between the Elbe and the Oder, Western Pomerania, Prussia, western Poland, the Czech lands (and especially Moravia), Carinthia and Transylvania."

- doi:10.4000/rga.1359. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ ISBN 978-963-9116-67-2.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-86583-165-1.

- ^ a b Palgrave Macmillan UK 1999, p. 12.

- ^ Bartlett 1998, p. 184.

- ^ Bartlett 1998, p. 187.

- ISBN 978-3-631-54117-3.

- ISBN 978-1-55753-443-9.

- ISBN 978-3-8252-8324-7.

- ISBN 3-11-017061-2.

- ^ ISBN 3-11-017061-2.

- ^ Anna Paner, Jan Iluk: Historia Polski Virtual Library of Polish Literature, Katedra Kulturoznawstwa, Wydział Filologiczny, Uniwersytet Gdański..

- ^ ISBN 978-3-423-04540-7.

- ISBN 3-8252-2105-9.

- ^ ISBN 3-11-017061-2.

- ^ a b Schich 2007, p. 217.

- ^ Bartlett 1998, p. 326.

- ^ Bartlett 1998, p. 320.

- ^ Schich 2007, p. 218.

- ^ Martin Stolzenau (3 February 2019). "Er schuf die Grundlage für die Stadt- und Landeshistorie". MAZ. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ^ Enno Bünz: Die Rolle der Niederländer in der Ostsiedlung, in: Ostsiedlung und Landesausbau in Sachsen, 2008.

- ^ a b Konrad Gündisch. "Transylvania and the Transylvanian Saxons". Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ Bartlett 1998, p. 148.

- ^ Szabo 2008, p. 11.

- ^ a b c Szabo 2008, p. 12.

- ^ Herbers & Jaspert 2007.

- ^ Tomasz Czarnecki. "V. Internationale Germanistische Konferenz: "Deutsch im Kontakt der Kulturen. Schlesien und andere Vergleichsregionen" – Tomasz Czarnecki: Die deutschen Lehnwörter im Polnischen und die mittelalterlichen Dialekte des schlesischen Deutsch". Doc Player. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ Tilman Berger, Ingrid Hudabiunigg. "Geschichte des deutsch-slawischen Sprachkontaktes im Teschener Schlesie" (PDF). Uni Regensburg. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- ^ Pavla Kloboukov. "Germanismy v Běžné Mluvě Dneška" (PDF). Masaryk University Philosophy Faculty. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- JSTOR 40499525. Retrieved 30 September 2020 – via Jstor.

- ISBN 3-11-007895-3.

- ISBN 978-0-85261-947-6.

- doi:10.58938/ni605.

- ISBN 978-3-11-018626-0. Retrieved 9 August 2023.

- ^ Klaus Fehn. "Siedlungsforschung Archäologie-Geschichte-Geographie, Band 13 – pp. 67 – 77" (PDF). Verlag Siedlungsforschung Bonn. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 March 2022. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- ISBN 978-3-534-07556-0.

- ^ Janusz Gumkowkski, Kazimierz Leszczynski. "Hitler's Plans for Eastern Europe". archive. Archived from the original on 27 May 2012. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ISBN 978-3-88680-771-0.

- ^ DIETRICH EICHHOLTZ. "Generalplan Ost" zur Versklavungosteuropäischer Völker" (PDF). Archive. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 March 2016. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ^ WALTER SCHLESINGER. "DIE GESCHICHTLICHE STELLUNG DER MITTELALTERLICHEN DEUTSCHEN OSTBEWEGUNG". De Gruyter. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ^ a b STEFFEN PRAUSER, ARFON REES. "The Expulsion of the German Communities from Eastern Europe at the End of the Second World War". EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE, FLORENCE. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

Sources

- Bartlett, Robert (1998). Die Geburt Europas aus dem Geist der Gewalt. Eroberung, Kolonisation und kultureller Wandel von 950 bis 1350 ( = [English original :] The Making of Europe : conquest, colonization, and cultural change 950 – 1350) (in German). Knaur München. ISBN 3-426-60639-9.

- Kleineberg, A; Marx, Chr; Knobloch, E.; Lelgemann, D. (2010). Germania und die Insel Thule. Die Entschlüsselung von Ptolemaios' "Atlas der Oikumene" (in German). WBG. ISBN 978-3-534-23757-9.

- Gründer, Horst; Johanek, Peter (2001). Kolonialstädte, europäische Enklaven oder Schmelztiegel der Kulturen?: Europäische Enklaven oder Schmelztiegel der Kulturen? (in German). LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 3-8258-3601-0.

- Reuber, Paul; Strüver, Anke; Wolkersdorfer, Günter (2005). Politische Geographien Europas – Annäherungen an ein umstrittenes Konstrukt: Annäherungen an ein umstrittenes Konstrukt (in German). ISBN 3-8258-6523-1.

- Demurger, Alain; Kaiser, Wolfgang (2003). Die Ritter des Herrn: Geschichte der Geistlichen Ritterorden (in German). C.H.Beck. ISBN 3-406-50282-2.

- Herbers, Klaus; Jaspert, Nikolas, eds. (2007). Grenzräume und Grenzüberschreitungen im Vergleich: Der Osten und der Westen des mittelalterlichen Lateineuropa (in German). De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-05-004155-1.

- "Die Slawen in Deutschland. Geschichte und Kultur der slawischen Stämme westlich von Oder und Neiße : Joachim Herrmann, Autorenkollektiv: Amazon.de: Bücher". amazon.de (in German). 23 June 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- Knefelkamp, Ulrich, ed. (2001). Zisterzienser: Norm, Kultur, Reform – 900 Jahre Zisterzienser (in German). Springer. ISBN 3-540-64816-X.

- Minahan, James (2000). "Germans". One Europe, Many Nations: A Historical Dictionary of European National Groups. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-30984-1. Retrieved 11 March 2016.

- Schich, Winfried (2007). Wirtschaft und Kulturlandschaft: Gesammelte Beiträge 1977 bis 1999 zur Geschichte der Zisterzienser und der "Germania Slavica". Bibliothek der brandenburgischen und preussischen Geschichte (in German). Vol. 12. BWV Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8305-0378-1.

- Rösener, Werner (1988). Agrarwirtschaft, Agrarverfassung und ländliche Gesellschaft im Mittelalter (in German). Oldenbourg. ISBN 3-486-55024-1.

- Schulman, Jana K. (2002). The Rise of the Medieval World, 500–1300: A Biographical Dictionary. Greenwood Press.

- Sommerfeld, Wilhelm von (2005) [1896]. Geschichte der Germanisierung des Herzogtums Pommern oder Slavien bis zum Ablauf des 13. Jahrhunderts (in German). Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 1-4212-3832-2. (unabridged facsimile of the edition published by Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1896)

- Szabo, Franz A. J. (2008). Ingrao, Charles W. (ed.). The Germans and the East. Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-443-9.

- Bartlett, Roger; Schönwälder, Karen, eds. (1999). The German Lands and Eastern Europe. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. ISBN 978-1-349-27096-5.

- Szende, Katalin (9 May 2019). "Iure Theutonico? German settlers and legal frameworks for immigration to Hungary in an East-Central European perspective". Journal of Medieval History. 45 (3). ISSN 0304-4181.

Further reading

- Charles Higounet (1911–1988) Les allemands en Europe centrale et oriental au moyen age

- German translation: Die deutsche Ostsiedlung im Mittelalter

- Japanese translation: ドイツ植民と東欧世界の形成, 彩流社, by Naoki Miyajima

- Bielfeldt et al., Die Slawen in Deutschland. Ein Handbuch, Hg. Joachim Herrmann, Akademie-Verlag Berlin, 1985