Otú Norte Fault

| Otú Norte Fault | ||

|---|---|---|

| Falla de Otú Norte Otú-Pericos Fault | ||

Age Quaternary | | |

| Orogeny | Andean | |

The Otú Norte or Otú-Pericos Fault (

Etymology

The fault was by Feininger et al. in 1972 named after Otú Airport in vereda Otú in Remedios, Antioquia.[1]

Description

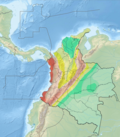

The Otú Norte Fault crosses the northern part of the

Activity

A rate of less than 0.2 millimetres (0.0079 in) per year is estimated for the fault, considered inactive. Displaced Quaternary terraces as high as 140 metres (460 ft) are reported and the fault offsets the Tertiary erosion surface of the Central Ranges.[6] A total displacement of the fault has been estimated at 66 kilometres (41 mi).[7]

Economic importance

The fault separates two major gold mining areas in Antioquia; the Segovia-Remedios mining district and La Ye mine in the east,[8][9] and the placer deposits of Gramalote and Cisneros in the west.[10][11] North of Zaragoza, the fault underlies the El Limón mine.[12] Antioquia produces 50% of all gold in Colombia.[13]

The ductile zone of the fault produced

See also

References

- ^ Consorcio GSG, 2015, p.168

- ^ Fonseca et al., 2011, p.40

- ^ Fonseca et al., 2011, p.64

- ^ Geological Map of Antioquia, 1999

- ^ Paris et al., 2000, p.28

- ^ Paris et al., 2000, p.29

- ^ Álvarez et al., 2007, p.49

- ^ Segovia-Remedios mining district

- ^ Mining Atlas - La Ye

- ^ Mining Atlas - Gramalote

- ^ Mining Technology - Cisneros

- ^ Mining Atlas - El Limón

- ^ Fonseca et al., 2011, p.126

- ^ Álvarez et al., 2007, p.47

- ^ Álvarez et al., 2007, p.48

Bibliography

- Álvarez Galindez, Milton; Oswaldo Ordóñez Carmona; Mauricio Valencia Marín, and Antonio Romero Hernández. 2007. Geología de la zona de influencia de la Falla Otú en el Distrito Minero Segovia-Remedios - Geology of the influence zone of the Otú Fault in the Segovia-Remedios mining district. Dyna 74. 41–51. Accessed 2018-06-05.

- Consorcio, GSG. 2015. Memoria Plancha 94 - El Bagre - 1:100,000, 1–196. Servicio Geológico Colombiano.

- Fonseca P. et al, Héctor Antonio. 2011. Memoria Plancha 133 - Puerto Berrío - 1:100,000, 1–145. INGEOMINAS.

- Paris, Gabriel; Michael N. Machette; Richard L. Dart, and Kathleen M. Haller. 2000a. Map and Database of Quaternary Faults and Folds in Colombia and its Offshore Regions, 1–66. USGS. Accessed 2017-09-18.

Maps

- González, Humberto; Ubaldo Cossio; Mario Maya; Edgar Vásquez, and Magdalí Holguín. 1999. Mapa Geológico de Antioquia 1:400,000, 1. INGEOMINAS. Accessed 2017-09-21.

- Paris, Gabriel; Michael N. Machette; Richard L. Dart, and Kathleen M. Haller. 2000b. Map of Quaternary Faults and Folds of Colombia and Its Offshore Regions, 1. USGS. Accessed 2017-09-18.

Further reading

- Page, W.D. 1986. Seismic geology and seismicity of Northwestern Colombia, 1–200. San Francisco, California, Woodward-Clyde Consultants Report for ISA and Integral Ltda., Medellín.