Armenians in the Ottoman Empire

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

| History of Armenia |

|---|

|

| Timeline • Origins • Etymology |

Social structure |

| Court and aristocracy |

|---|

| Ethnoreligious communities |

| Rise of nationalism |

| Classes |

The

Background

The Ottomans introduced a number of unique approaches to governing into the traditions of

The Armenian population's integration was partly due to the nonexistent structural rigidity throughout the initial period.

During the Byzantine period, the Armenian Church was not allowed to operate in Constantinople, because the Greek Orthodox Church regarded the Armenian Church as heretical. With the establishment of Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, Armenians became religious leaders, and bureaucrats under the Ottoman Empire became more influential than just their own community. The idea that two separate "establishments" shared state power gave people a chance to occupy important positions, administrative, the religious-legal, and the social-economic.

Armenians occupied important posts within the Ottoman Empire, Artin Dadyan Pasha, who served as minister of foreign affairs from 1876 to 1901, is one of many examples of Armenian citizens who played a fundamental role in the sociopolitical sphere of the Ottoman Empire.

Role of Armenians in the Ottoman economy

Certain elite Armenian families in the Ottoman Empire gained the trust of the Sultans and were able to achieve important positions in the Ottoman government and the Ottoman economy. Even though their numbers were small compared to the whole Ottoman Armenian population, this caused some resentment among Ottoman nationalists. The life of the rest of the common Armenians was a very difficult existence because they were treated as second class citizens. Those elite Armenians that did achieve great success were individuals such as

Patriarchate of Constantinople

After

Until the promulgation of the

Armenian village life

In villages, including those of which the population was chiefly Muslim, the Armenian quarters were settled in groups among other parts of the population. Compared to others, Armenians lived in well-built homes. The houses were arranged one above the other, so that the flat roof of the lower house serves as the front yard of the one above it. For safety, the houses were huddled together. Armenian dwellings were adapted to the extremes of temperature in the highlands of

The

Ottoman Armenia, 1453–1829

After many centuries of

In addition, there were the century-long

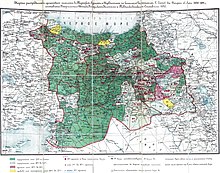

Owing to these events, the composition of the population had undergone (ever since the second half of the medieval period) a transformation so profound that the

There were also significant communities in parts of

Western Armenia, 1829–1918

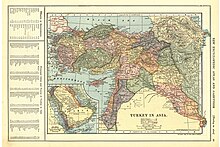

The remaining Ottoman Armenia, composed of the

Armenians during the 19th century

Aside from the learned professions taught at the schools that had

Many Armenians, who after having emigrated to foreign countries and becoming prosperous there, returned to their native land.[13] Alex Manoogian who became a philanthropist and active member of the Armenian General Benevolent Union was from Ottoman lands (modern İzmir), Arthur Edmund Carewe, born Trebizond, become an actor in the silent film era.

Armenians occupied important posts within the Ottoman Empire, Artin Dadyan Pasha served as Minister of foreign affairs of the Ottoman Empire from 1876 to 1901 and is an example that Armenian citizens served the Ottoman Empire.

Eastern Question

The

The Eastern Question gained even more traction by the late 1820s, due to the

Reform implementation, 1860s–1880s

The three major European powers – Great Britain, France and Russia (known as the Great Powers) – took issue with the Empire's treatment of its Christian minorities and increasingly pressured the Ottoman government (also known as the Sublime Porte) to extend equal rights to all its citizens.

Beginning in 1839, the Ottoman government implemented the

Armenian National Constitution, 1863

In 1863, the Armenian National Constitution (Ottoman Turkish:"Nizâmnâme-i Millet-i Ermeniyân") was Ottoman Empire approved. It was a form of the "Code of Regulations" composed of 150 articles drafted by the "Armenian intelligentsia", which defined the powers of Patriarch (a position in the Ottoman Millet) and newly formed "Armenian National Assembly".[17] Mikrtich issued a decree permitting women to have equal votes with men and asking them to take part in all elections.

The Armenian National Assembly had wide-ranging functions. Muslim officials were not employed to collect taxes in Armenian villages, but the taxes in all the Armenian villages collected by Armenian tax-gatherers appointed by the Armenian National Assembly. Armenians were allowed to establish their own courts of justice for the purpose of administering justice and conducting litigation between Armenians, and for deciding all questions relating to marriage, divorce, estate, inheritance, etc., appertaining to themselves. Also Armenians were allowed the right to establish their own prisons for the incarceration of offending Armenians, and in no case should an Armenian be imprisoned in an Ottoman prison.

The Armenian National Assembly also had the power to elect the Armenian Governor by a local Armenian legislative council. The councils later will be part of elections during second constitutional era. Local Armenian legislative councils were composed of six Armenians elected by the Armenian National Assembly.

Education and social work

Beginning in 1863, education was available to all subjects, as far as funds permitted it. Such education was under the direction of lay committees. During this period in Russian Armenia, the association of the schools with the Church was close, but the same principle obtains. This became a problem for the Russian administration, which peaked during 1897 when Tsar Nicholas appointed the Armenophobic Grigory Sergeyevich Golitsin as governor of Transcaucasia, and Armenian schools, cultural associations, newspapers and libraries were closed.

The Armenian charitable works, hospitals, and provident institutions were organized along the explained perspective. The Armenians, in addition to paying taxes to the State, voluntarily imposed extra burdens on themselves in order to support these philanthropic agencies. The taxes to the State did not have direct return to Armenians in such cases.

Armenian Question, 1877

The

National awakening, 1880s

The national liberation movement of the Balkan peoples (see:

Sultan Abdul Hamid II, 1876–1909

Abdul Hamid II was the 34th Sultan and oversaw a period of decline in the power and extent of the Empire, ruling from 31 August 1876 until he was deposed on 27 April 1909. He was the last Ottoman Sultan to rule with absolute power.

Bashkaleh clash, 1889

The Bashkaleh clash was the bloody encounter between the

Kum Kapu demonstration, 1890

The

Bloody years, 1894–96

The first notable battle in the Armenian resistance movement took place in

The

Sasun Uprising, 1904

Ottoman officials involved in the

Assassination attempt on Sultan Abdul Hamid II, 1905

The events of the

Dissolution, 1908–18

Young Turk Revolution, 1908

On 24 July 1908, Armenians' hopes for equality in the empire brightened with the removal of Hamid II from power and restored the country back to a constitutional monarchy. Two of the largest revolutionary groups trying to overthrow Sultan Abdul Hamid II had been the

Balkan Wars

Andranik Ozanian participated in the Balkan Wars of 1912–1913 alongside general Garegin Nzhdeh as a commander of Armenian auxiliary troops. Andranik met revolutionist Boris Sarafov and the two pledged to work jointly for the oppressed peoples of Armenia and Macedonia. Andranik participated in the First Balkan War alongside Nzhdeh as a Chief Commander of 12th Battalion of Lozengrad Third Brigade of the Macedonian-Adrianopolitan militia under the command of Colonel Aleksandar Protogerov. His detachment consisted of 273 Armenian volunteers. On 5 May 1912, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation officially severed the relations with the Ottoman government; a public declaration of the Western Bureau printed in the official announcement was directed to "Ottoman Citizens". The June issue of Droshak ran an editorial about it.[30]: 35 There were overwhelming numbers of Armenians who served the Empire units with distinction during Balkan wars.

Armenian reform package, 1914

The

Population

| Vilayet | Localities | Armenians | Churches | Monasteries | Schools | Pupils |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constantinople | 49 | 163,670 | 53 | 64 | ||

| Thrace | 9 | 30,316 | 14 | 15 | 2,438 | |

| Sanjak of Ismet | 42 | 61,675 | 51 | 53 | 7,480 | |

| Hüdavendigâr | 58 | 118,992 | 54 | 50 | 6,699 | |

Aidin

|

16 | 21,145 | 26 | 1 | 27 | 2,935 |

| Konya | 15 | 20,738 | 14 | 1 | 26 | 4,585 |

| Kastamonu | 18 | 13,461 | 17 | 18 | 2,500 | |

| Trebizond | 118 | 73,395 | 106 | 31 | 90 | 9,254 |

| Angora | 88 | 135,869 | 105 | 11 | 126 | 21,298 |

| Sivas | 241 | 204,472 | 198 | 21 | 204 | 20,599 |

| Adana | 70 | 119,414 | 44 | 5 | 63 | 5,834 |

| Aleppo | 117 | 189,565 | 93 | 16 | 113 | 8,451 |

| Mamuret-ul-Aziz | 279 | 124,289 | 242 | 65 | 204 | 15,632 |

| Diyarbakir | 249 | 106,867 | 148 | 10 | 122 | 9,660 |

| Erzurum | 425 | 202,391 | 406 | 76 | 322 | 21,348 |

| Bitlis | 681 | 218,404 | 510 | 161 | 207 | 9,309 |

| Van | 450 | 110,897 | 457 | 80 | 192 | |

| TOTAL | 2,925 | 1,914,620 | 2,538 | 451 | 1,996 | 173,022 |

World War I, 1914–18

During World War I, the

See also

- History of Armenia

- Timeline of Armenian history

- Armenians in Turkey

- Anti-Armenian sentiment in Turkey

- Ottoman Armenian population

- Armenian Patriarch of Constantinople

- Armenian Sport in the Ottoman Empire

References

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-927356-0.

- ISBN 978-1-84854-647-9.

- ^ Minasyan, Smbat (21 June 2008). "Armenia as Xenophon saw it". Archived from the original on 27 August 2008. Retrieved 3 September 2008.

- ^ Anabasis (Xenophon), IV.v.2–9.[verification needed]

- ^ We and They: Armenians in the Ottoman Empire Archived 21 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ISBN 975-263-490-7(the book is in Turkish)

- ^ Wolf-Dieter Hütteroth and Volker Höhfeld. Türkei, Darmstadt 2002. pp. 128–132.

- ^ M. Canard: "Armīniya" in Encyclopaedia of Islam, Leiden 1993.

- ^ G. L. Selenoy and N. von Seidlitz: "Die Verbreitung der Armenier in der asiatischen Türkei und in Trans-Kaukassien", in: Petermanns Mitteilungen, Gotha 1896.

- ^ McCarthy, Justin: The Ottoman Peoples and the end of Empire; London, 1981; p.86

- ISBN 9781412807753.

- ^ Cahoon, Ben (2000). "Armenia". WorldStatesmen.org..

- ^ Johansson, Alice (January 2008). "Return Migration to Armenia" (PDF). Radboud Universiteit.[permanent dead link]

- ISBN 1-57181-666-6

- ^ Hovannisian, Richard, The Armenian Genocide: History, Politics, Ethics, pg.129

- Ortayli, Ilber, Tanzimattan Cumhuriyete Yerel Yönetim Gelenegi, Istanbul 1985, pp. 73

- ^ Hovannisian, Richard "The Armenian People from Ancient to Modern Times" pg.198

- ^ Armenian Studies: Études Arméniennes by Lebanese Association of Armenian University Graduates, pp. 4–6

- ^ Kirakossian, Arman J. British Diplomacy and the Armenian Question: From the 1830s to 1914, page 58

- ^ Ter-Minasian, Ruben. Hai Heghapokhakani Me Hishataknere [Memoirs of an Armenian Revolutionary] (Los Angeles, 1952), II, 268–269.

- ^ Darbinian, op. cit., p. 123; Adjemian, op. cit., p. 7; Varandian, Dashnaktsuthian Patmuthiun, I, 30; Great Britain, Turkey No. 1 (1889), op. cit., Inclosure in no. 95. Extract from the "Eastern Express" of 25 June 1889, pp. 83–84; ibid., no. 102. Sir W. White to the Marquis of Salisbury-(Received 15 July), p. 89; Great Britain, Turkey No. 1 (1890), op. cit., no. 4. Sir W. White to the Marquis of Salisbury-(Received 9 August), p. 4; ibid., Inclosure 1 in no. 4, Colonel Chermside to Sir W. White, p. 4; ibid., Inclosure 2 in no. 4. Vice-Consul Devey to Colonel Chermside, pp. 4–7; ibid., Inclosure 3 in no. 4. M. Patiguian to M. Koulaksizian, pp. 7–9; ibid., Inclosure 4 in no.

- ^ a b c Creasy, Edward Shepherd. Turkey, pg.500.

- ^ Kurdoghlian, Mihran (1996). Hayots Badmoutioun, Volume III (in Armenian). Athens, Greece: Hradaragoutioun Azkayin Ousoumnagan Khorhourti. pp. 42–44.

- ^ Balakian, Peter. The Burning Tigris: The Armenian Genocide and America's Response. New York: Perennial, 2003. pp. 107–108

- Akcam, Taner. A Shameful Act. 2006, pg.42.

- ^ Kurdoghlian, Mihran (1996). Hayots Badmoutioun, Volume III (in Armenian). Athens, Greece: Hradaragoutioun Azkayin Ousoumnagan Khorhourti. p. 47.

- ^ Kirakosian, Arman Dzhonovich. The Armenian Massacres, 1894–1896: 1894–1896 : U.S. media testimony, Page 33.

- ^ ISBN 90-04-10283-3.

- ^ Kurdoghlian, Mihran (1996). Hayots Badmoutioun (Armenian History) (in Armenian). Athens, Greece: Hradaragutiun Azkayin Oosoomnagan Khorhoortee. pp. 52–53.

- ISBN 978-1137362209.

- ^ Kirakosian, J. S., ed. Hayastane michazkayin divanakitut'yan ew sovetakan artakin kaghakakanut'yan pastateghterum, 1828–1923 (Armenia in the documents of international diplomacy and Soviet foreign policy, 1828–1923). Erevan, 1972. p.149-358

- OCLC 742353455.

Further reading

- Frazee, Charles A. (2006) [1983]. Catholics and Sultans: The Church and the Ottoman Empire 1453–1923. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521027007.

- Stopka, Krzysztof (2016). Armenia Christiana: Armenian Religious Identity and the Churches of Constantinople and Rome (4th-15th century). Kraków: Jagiellonian University Press. ISBN 9788323395553.