Ottoman Turkish

| Ottoman Turkish | |

|---|---|

| لسان عثمانى Lisân-ı Osmânî | |

| |

| Region | Ottoman Empire |

| Ethnicity | Ottoman Turks |

| Era | c. 15th century; developed into modern Turkish in 1928[1] |

Turkic

| |

Early form | |

Turkish Provisional Government | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | ota |

| ISO 639-3 | ota |

ota | |

| Glottolog | otto1234 |

Ottoman Turkish (

Consequently, Ottoman Turkish was largely unintelligible to the less-educated lower-class and to rural Turks, who continued to use kaba Türkçe ("raw/vulgar Turkish"; compare Vulgar Latin and Demotic Greek), which used far fewer foreign loanwords and is the basis of the modern standard.[5] The Tanzimât era (1839–1876) saw the application of the term "Ottoman" when referring to the language[6] (لسان عثمانی lisân-ı Osmânî or عثمانليجه Osmanlıca); Modern Turkish uses the same terms when referring to the language of that era (Osmanlıca and Osmanlı Türkçesi). More generically, the Turkish language was called تركچه Türkçe or تركی Türkî "Turkish".

Grammar

Cases

- Nominative and Indefinite accusative/objective: -∅, no suffix. كول göl 'the lake' 'a lake', چوربا çorba 'soup', كیجه gece 'night'; طاوشان گترمش ṭavşan getirmiş 'he/she brought a rabbit'.

- Genitive: suffix ڭ/نڭ –(n)ıñ, –(n)iñ, –(n)uñ, –(n)üñ. پاشانڭ paşanıñ 'of the pasha'; كتابڭ kitabıñ 'of the book'.

- Definite accusative: suffix ى –ı, -i: طاوشانى كترمش ṭavşanı getürmiş 'he/she brought the rabbit'. The variant suffix –u, –ü does not occur in Ottoman Turkish orthography (unlike in Modern Turkish), although it's pronounced with the vowel harmony. Thus, كولى göli 'the lake' vs. Modern Turkish gölü.[7]

- Dative: suffix ه –e: اوه eve 'to the house'.

- Locative: suffix ده –de, –da: مكتبده mektebde 'at school', قفسده ḳafeṣde 'in (the/a) cage', باشده başda 'at a/the start', شهرده şehirde 'in town'. The variant suffix used in Modern Turkish (–te, –ta) does not occur.

- Ablative: suffix دن –den, -dan: ادمدن adamdan 'from the man'.

- Instrumental: suffix or postposition ايله ile. Generally not counted as a grammatical case in modern grammars.

Verbs

The conjugation for the aorist tense is as follows:

| Singular | Plural | |

|---|---|---|

| 1st person | -irim | -iriz |

| 2nd person | -irsiŋ | -irsiŋiz |

| 3rd person | -ir | -irler |

Structure

Ottoman Turkish was highly influenced by Arabic and Persian. Arabic and Persian words in the language accounted for up to 88% of its vocabulary.

The conservation of archaic phonological features of the Arabic borrowings furthermore suggests that Arabic-incorporated Persian was absorbed into pre-Ottoman

In a social and pragmatic sense, there were (at least) three variants of Ottoman Turkish:

- Fasih Türkçe (Eloquent Turkish): the language of poetry and administration, Ottoman Turkish in its strict sense;

- Orta Türkçe (Middle Turkish): the language of higher classes and trade;

- Kaba Türkçe (Rough Turkish): the language of lower classes.

A person would use each of the varieties above for different purposes, with the fasih variant being the most heavily suffused with Arabic and Persian words and kaba the least. For example, a scribe would use the Arabic asel (عسل) to refer to honey when writing a document but would use the native Turkish word bal when buying it.

History

Historically, Ottoman Turkish was transformed in three eras:

- Eski Osmanlı Türkçesi (Old Ottoman Turkish): the version of Ottoman Turkish used until the 16th century. It was almost identical with the Turkish used by Seljuk empire and Anatolian beyliks and was often regarded as part of Eski Anadolu Türkçesi (Old Anatolian Turkish).

- Orta Osmanlı Türkçesi (Middle Ottoman Turkish) or Klasik Osmanlıca (Classical Ottoman Turkish): the language of poetry and administration from the 16th century until Tanzimat.

- Yeni Osmanlı Türkçesi (New Ottoman Turkish): the version shaped from the 1850s to the 20th century under the influence of journalism and Western-oriented literature.

Language reform

In 1928, following the

See the list of replaced loanwords in Turkish for more examples of Ottoman Turkish words and their modern Turkish counterparts. Two examples of Arabic and two of Persian loanwords are found below.

| English | Ottoman | Modern Turkish |

|---|---|---|

| obligatory | واجب vâcib | zorunlu |

| hardship | مشكل müşkül | güçlük |

| city | شهر şehir | kent (also şehir) |

| province | ولایت vilâyet | il |

| war | حرب harb | savaş |

Legacy

Historically speaking, Ottoman Turkish is the predecessor of modern Turkish. However, the standard Turkish of today is essentially Türkiye Türkçesi (Turkish of Turkey) as written in the Latin alphabet and with an abundance of

In 2014, Turkey's Education Council decided that Ottoman Turkish should be taught in Islamic high schools and as an elective in other schools, a decision backed by President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who said the language should be taught in schools so younger generations do not lose touch with their cultural heritage.[13]

Writing system

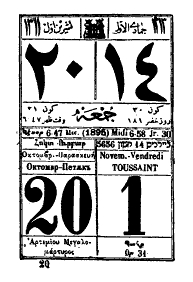

Most Ottoman Turkish was written in the

Numbers

1 |

١ |

بر |

bir |

2 |

٢ |

ایكی |

iki |

3 |

٣ |

اوچ |

üç |

4 |

٤ |

درت |

dört |

5 |

٥ |

بش |

beş |

6 |

٦ |

آلتی |

altı |

7 |

٧ |

یدی |

yedi |

8 |

٨ |

سكز |

sekiz |

9 |

٩ |

طقوز |

dokuz |

10 |

١٠ |

اون |

on |

11 |

١١ |

اون بر |

on bir |

12 |

١٢ |

اون ایکی |

on iki |

Transliterations

The transliteration system of the İslâm Ansiklopedisi has become a de facto standard in Oriental studies for the transliteration of Ottoman Turkish texts.[15] Concerning transcription the New Redhouse, Karl Steuerwald and Ferit Develioğlu dictionaries have become standard.[16] Another transliteration system is the Deutsche Morgenländische Gesellschaft (DMG), which provides a transliteration system for any Turkic language written in Arabic script.[17] There are not many differences between the İA and the DMG transliteration systems.

| ا | ب | پ | ت | ث | ج | چ | ح | خ | د | ذ | ر | ز | ژ | س | ش | ص | ض | ط | ظ | ع | غ | ف | ق | ك | گ | ڭ | ل | م | ن | و | ه | ى |

| ʾ/ā | b | p | t | s | c | ç | ḥ | ḫ | d | ẕ | r | z | j | s | ş | ṣ | ż | ṭ | ẓ | ʿ | ġ | f | ḳ | k,g,ñ,ğ | g | ñ | l | m | n | v | h | y |

See also

- Old Anatolian Turkish language

- Culture of the Ottoman Empire

- List of Persian loanwords in Turkish

Notes

References

- ^ "Turkey – Language Reform: From Ottoman To Turkish". Countrystudies.us. Archived from the original on 9 April 2016. Retrieved 24 May 2016.

- ^ "5662". DergiPark.

- ISBN 9789004149762.

- ^ ISBN 9971774887p 69

- ^ Glenny, Misha (2001). The Balkans — Nationalism, War, and the Great Powers, 1804–1999. Penguin. p. 99.

- ISBN 0415082005.

- ^ Redhouse, William James. A Simplified Grammar of the Ottoman-Turkish Language. p. 52.

- ^ Percy Ellen Algernon Frederick William Smythe Strangford, Percy Clinton Sydney Smythe Strangford, Emily Anne Beaufort Smythe Strangford, "Original Letters and Papers of the late Viscount Strangford upon Philological and Kindred Subjects", Published by Trübner, 1878. pg 46: "The Arabic words in Turkish have all decidedly come through a Persian channel. I can hardly think of an exception, except in quite late days, when Arabic words have been used in Turkish in a different sense from that borne by them in Persian."

- ^ M. Sukru Hanioglu, "A Brief History of the Late Ottoman Empire", Published by Princeton University Press, 2008. p. 34: "It employed a predominant Turkish syntax, but was heavily influenced by Persian and (initially through Persian) Arabic.

- ^ Pierre A. MacKay, "The Fountain at Hadji Mustapha", Hesperia, Vol. 36, No. 2 (Apr. – Jun., 1967), pp. 193–195: "The immense Arabic contribution to the lexicon of Ottoman Turkish came rather through Persian than directly, and the sound of Arabic words in Persian syntax would be far more familiar to a Turkish ear than correct Arabic".

- ^ ISBN 978-1134006557p XV.

- S2CID 162474551.

- ^ Pamuk, Humeyra (December 9, 2014). "Erdogan's Ottoman language drive faces backlash in Turkey". Reuters. Istanbul. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- ^ Hagopian, V. H. (5 May 2018). "Ottoman-Turkish conversation-grammar; a practical method of learning the Ottoman-Turkish language". Heidelberg, J. Groos; New York, Brentano's [etc., etc.] Archived from the original on 24 May 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Korkut Buğday Osmanisch, p. 2

- ^ Korkut Buğday Osmanisch, p. 13

- ^ Transkriptionskommission der DMG Die Transliteration der arabischen Schrift in ihrer Anwendung auf die Hauptliteratursprachen der islamischen Welt, p. 9 Archived 2012-07-22 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Korkut Buğday Osmanisch, p. 2f.

Further reading

- English

- V. H. Hagopian (1907). Ottoman-Turkish conversation-grammar: a practical method of learning the Ottoman-Turkish language, Volume 1. D. Nutt. Online copies: [1], [2], [3]

- Charles Wells (1880). A practical grammar of the Turkish language (as spoken and written). B. Quaritch. Online copies from Google Books: [4], [5], [6]

- V. H. Hagopian (1908). Key to the Ottoman-Turkish conversation-grammar. Nutt.

- Sir James William Redhouse (1884). A simplified grammar of the Ottoman-Turkish language. Trübner.

- Frank Lawrence Hopkins (1877). Elementary grammar of the Turkish language: with a few easy exercises. Trübner.

- Sir James William Redhouse (1856). An English and Turkish dictionary: in two parts, English and Turkish, and Turkish and English. B. Quarich.

- Sir James William Redhouse (1877). A lexicon, English and Turkish: shewing in Turkish, the literal, incidental, figurative, colloquial, and technical significations of the English terms, indicating their pronunciation in a new and systematic manner; and preceded by a sketch of English etymology, to facilitate to Turkish students ... (2nd ed.). Printed for the mission by A.H. Boyajian.

- Charles Boyd, Charles Boyd (Major.) (1842). The Turkish interpreter: or, A new grammar of the Turkish language. Printed for the author.

- Thomas Vaughan (1709). A Grammar of The Turkish Language. Robinson.

- William Burckhardt Barker (1854). A practical grammar of the Turkish language: With dialogues and vocabulary. B. Quaritch.

- William Burckhardt Barker, Nasr-al-Din (khwajah.) (1854). A reading book of the Turkish language: with a grammar and vocabulary ; containing a selection of original tales, literally translated, and accompanied by grammatical references : the pronunciation of each word given as now used in Constantinople. J. Madden.

- James William Redhouse (sir.) (1855). The Turkish campaigner's vade-mecum of Ottoman colloquial language.

- Lewis, Geoffrey. The Jarring Lecture 2002. "The Turkish Language Reform: A Catastrophic Success".

- Other languages

- Mehmet Hakkı Suçin. Qawâ'id al-Lugha al-Turkiyya li Ghair al-Natiqeen Biha (Turkish Grammar for Arabs; adapted from Mehmet Hengirmen's Yabancılara Türkçe Dilbilgisi), Engin Yayınevi, 2003).

- Mehmet Hakkı Suçin. Atatürk'ün Okuduğu Kitaplar: Endülüs Tarihi (Books That AtatürkRead: History of Andalucia; purification from the Ottoman Turkish, published by Anıtkabir Vakfı, 2001).

- Kerslake, Celia (1998). "La construction d'une langue nationale sortie d'un vernaculaire impérial enflé: la transformation stylistique et conceptuelle du turc ottoman". In Chaker, Salem (ed.). Langues et Pouvoir de l'Afrique du Nord à l'Extrême-Orient. Aix-en-Provence: Edisud. pp. 129–138.

- Korkut M. Buğday (1999). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag (ed.). Osmanisch: Einführung in die Grundlagen der Literatursprache.

External links

- Turkish dictionaries at Curlie

- Turkish language at Curlie

- Latin to Ottoman Turkish transliteration

- Ottoman Text Archive Project

- Ottoman Turkish Language: Resources – University of Michigan

- Ottoman Turkish Language Texts

- Ottoman-Turkish-English Open Dictionary

- Ottoman<>Turkish Dictionary – University of Pamukkale You can use ? character instead of an unknown letter. It provides results from Arabic and Persian dictionaries, too.

- Ottoman<>Turkish Dictionary – ihya.org