Oxalaia

| Oxalaia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Holotype snout in multiple views | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Spinosauridae |

| Genus: | †Oxalaia Kellner et al., 2011 |

| Species: | †O. quilombensis

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Oxalaia quilombensis Kellner et al., 2011

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Oxalaia (in reference to the African deity

Although Oxalaia is known only from two partial skull bones, Kellner and colleagues found that its teeth and

Discovery and naming

Oxalaia stems from the

Oxalaia is one of three

The discoveries of Oxalaia and of the Late Cretaceous reptiles

Specimen UFMA 1.10.240, a distal caudal vertebra which was discovered in the

Description

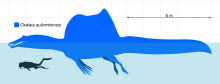

The holotype premaxillae are together approximately 201 millimetres (7.9 inches) long, with a preserved width of 115 mm (4.5 in) (maximal estimated original width is 126 mm (5.0 in)), and a height of 103 mm (4.1 in). Based on skeletal material from related spinosaurids, the skull of Oxalaia would have been an estimated 1.35 metres (4.4 feet) long;[5] this is smaller than Spinosaurus's skull, which was approximated at 1.75 m (5 ft 9 in) long by Italian palaeontologist Cristiano Dal Sasso and colleagues in 2005.[18] Kellner and his team compared the Dal Sasso specimen (MSNM V4047) to Oxalaia's original snout in 2011; from this they estimated Oxalaia at 12 to 14 m (39 to 46 ft) in length and 5 to 7 tonnes (5.5 to 7.7 short tons; 4.9 to 6.9 long tons) in weight, making it the largest known theropod from Brazil,[5] the second largest being Pycnonemosaurus, which was estimated at 8.9 m (29 ft) by one study.[15][19]

The tip of the

The premaxillae have seven

The spinosaurid teeth reported from Laje do Coringa were classified into two primary

Classification

The type elements of Oxalaia closely resemble those of specimens MSNM V4047 and MNHN SAM 124, both referred to Spinosaurus aegyptiacus. Kellner and colleagues differentiated Oxalaia from it and other spinosaurids by its

In 2017, a

In 2020, a paper by Robert Smyth and colleagues assessing spinosaurines from the

Palaeoecology

The Late Cretaceous deposits of the Alcântara Formation have been interpreted as a humid habitat of tropical forests dominated by

Most of the flora and fauna discovered in the Alcântara Formation was also present in North Africa in the

As a spinosaur, Oxalaia would have had large, robust forelimbs; relatively short hindlimbs; elongated

References

- ^ ISSN 0895-9811.

- ^ "GSA Geologic Time Scale". The Geological Society of America. Archived from the original on 2019-01-20. Retrieved 2018-06-13.

- .

- ISSN 0037-0738.

- ^ PMID 21437377.

- ^ a b c Janeiro, Priscila Bessa, iG Rio de (March 2011). "Museu Nacional anuncia descoberta de maior dinossauro brasileiro – Ciência – iG". Último Segundo (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 2018-06-12.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ISBN 9788571931848.

- S2CID 131339386.

- .

- ^ S2CID 90952478.

- ^ Bertin, Tor (2010). "A catalogue of material and review of the Spinosauridae". PalArch's Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology. 7 (4): 1–39.

- ^ Phillips, Dom (September 2018). "Brazil museum fire: 'incalculable' loss as 200-year-old Rio institution gutted". The Guardian. Retrieved 2018-09-03.

- ^ Lopes, Reinaldo José (September 2018). "Entenda a importância do acervo do Museu Nacional, destruído pelas chamas no RJ". Folha de S.Paulo (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 2018-09-03.

- ^ Mortimer, M. "Megalosauroidea". theropoddatabase.com. Retrieved 2018-11-06.

- ^ a b c "Museu Nacional anuncia descoberta do maior dinossauro carnívoro do Brasil – Notícias – Ciência". Ciência (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 2018-06-12.

- ^ a b c "Pictures: New Dinosaur, Crocodile Cousin Found in Brazil". National Geographic. March 2011. Archived from the original on March 31, 2011. Retrieved 2018-06-12.

- ^ Medeiros and Schultz, (2002). A fauna dinossauriana da Laje do Coringa, Cretáceo médio do Nordeste do Brasil. Arquivos do Museu Nacional. 60(3), 155-162.

- S2CID 85702490.

- .

- ^ a b c Milner, Andrew; Kirkland, James (September 2007). "The case for fishing dinosaurs at the St. George Dinosaur Discovery Site at Johnson Farm". Utah Geological Survey Notes. 39: 1–3.

- ^ PMID 29107966.

- .

- S2CID 53519187.

- S2CID 219487346.

- PMID 22146953.

- .

- S2CID 201321631.

- ISSN 0895-9811.

- from the original on 2018-10-23. Retrieved 2018-10-22.

- doi:10.1130/G30402.1.

External links

Data related to Oxalaia at Wikispecies

Data related to Oxalaia at Wikispecies