p53

| View/Edit Human | View/Edit Mouse |

p53, also known as Tumor protein P53, cellular tumor antigen p53 (UniProt name), or transformation-related protein 53 (TRP53) is a regulatory protein that is often mutated in human cancers. The p53 proteins (originally thought to be, and often spoken of as, a single protein) are crucial in vertebrates, where they prevent cancer formation.[5] As such, p53 has been described as "the guardian of the genome" because of its role in conserving stability by preventing genome mutation.[6] Hence TP53[note 1] is classified as a tumor suppressor gene.[7][8][9][10][11]

The TP53 gene is the most frequently mutated gene (>50%) in human cancer, indicating that the TP53 gene plays a crucial role in preventing cancer formation.[5] TP53 gene encodes proteins that bind to DNA and regulate gene expression to prevent mutations of the genome.[12] In addition to the full-length protein, the human TP53 gene encodes at least 12 protein isoforms.[13]

Gene

In humans, the TP53 gene is located on the short arm of

Human TP53 gene

In humans, a common

Meta-analyses from 2011 found no significant associations between TP53 codon 72 polymorphisms and both colorectal cancer risk[21] and endometrial cancer risk.[22] A 2011 study of a Brazilian birth cohort found an association between the non-mutant arginine TP53 and individuals without a family history of cancer.[23] Another 2011 study found that the p53 homozygous (Pro/Pro) genotype was associated with a significantly increased risk for renal cell carcinoma.[24]

Function

DNA damage and repair

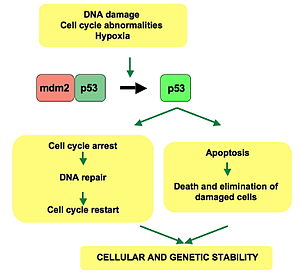

p53 plays a role in regulation or progression through the cell cycle, apoptosis, and genomic stability by means of several mechanisms:

- It can activate aging.[25]

- It can arrest growth by holding the cell cycle at the G1/S regulation point on DNA damage recognition—if it holds the cell here for long enough, the DNA repair proteins will have time to fix the damage and the cell will be allowed to continue the cell cycle.

- It can initiate apoptosis (i.e., programmed cell death) if DNA damage proves to be irreparable.

- It is essential for the senescence response to short telomeres.

WAF1/CIP1 encodes for

When p21(WAF1) is complexed with CDK2, the cell cannot continue to the next stage of cell division. A mutant p53 will no longer bind DNA in an effective way, and, as a consequence, the p21 protein will not be available to act as the "stop signal" for cell division.[26] Studies of human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) commonly describe the nonfunctional p53-p21 axis of the G1/S checkpoint pathway with subsequent relevance for cell cycle regulation and the DNA damage response (DDR). Importantly, p21 mRNA is clearly present and upregulated after the DDR in hESCs, but p21 protein is not detectable. In this cell type, p53 activates numerous microRNAs (like miR-302a, miR-302b, miR-302c, and miR-302d) that directly inhibit the p21 expression in hESCs.

The p21 protein binds directly to cyclin-CDK complexes that drive forward the cell cycle and inhibits their kinase activity, thereby causing cell cycle arrest to allow repair to take place. p21 can also mediate growth arrest associated with differentiation and a more permanent growth arrest associated with cellular senescence. The p21 gene contains several p53 response elements that mediate direct binding of the p53 protein, resulting in transcriptional activation of the gene encoding the p21 protein.

The p53 and RB1 pathways are linked via p14ARF, raising the possibility that the pathways may regulate each other.[27]

p53 expression can be stimulated by UV light, which also causes DNA damage. In this case, p53 can initiate events leading to tanning.[28][29]

Stem cells

Levels of p53 play an important role in the maintenance of stem cells throughout development and the rest of human life.

In human embryonic stem cells (hESCs)s, p53 is maintained at low inactive levels.[30] This is because activation of p53 leads to rapid differentiation of hESCs.[31] Studies have shown that knocking out p53 delays differentiation and that adding p53 causes spontaneous differentiation, showing how p53 promotes differentiation of hESCs and plays a key role in cell cycle as a differentiation regulator. When p53 becomes stabilized and activated in hESCs, it increases p21 to establish a longer G1. This typically leads to abolition of S-phase entry, which stops the cell cycle in G1, leading to differentiation. Work in mouse embryonic stem cells has recently shown however that the expression of P53 does not necessarily lead to differentiation.[32] p53 also activates miR-34a and miR-145, which then repress the hESCs pluripotency factors, further instigating differentiation.[30]

In adult stem cells, p53 regulation is important for maintenance of stemness in

Other

Apart from the cellular and molecular effects above, p53 has a tissue-level anticancer effect that works by inhibiting

p53 by regulating

The immune response to infection also involves p53 and NF-κB. Checkpoint control of the cell cycle and of apoptosis by p53 is inhibited by some infections such as Mycoplasma bacteria,[42] raising the specter of oncogenic infection.

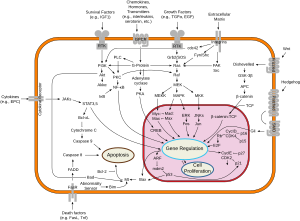

Regulation

p53 acts as a cellular stress sensor. It is normally kept at low levels by being constantly marked for degradation by the

The

In unstressed cells, p53 levels are kept low through a continuous degradation of p53. A protein called

MI-63 binds to MDM2, reactivating p53 in situations where p53's function has become inhibited.[47]

A ubiquitin specific protease,

Recent research has shown that HAUSP is mainly localized in the nucleus, though a fraction of it can be found in the cytoplasm and mitochondria. Overexpression of HAUSP results in p53 stabilization. However, depletion of HAUSP does not result in a decrease in p53 levels but rather increases p53 levels due to the fact that HAUSP binds and deubiquitinates Mdm2. It has been shown that HAUSP is a better binding partner to Mdm2 than p53 in unstressed cells.

USP10 however has been shown to be located in the cytoplasm in unstressed cells and deubiquitinates cytoplasmic p53, reversing Mdm2 ubiquitination. Following DNA damage, USP10 translocates to the nucleus and contributes to p53 stability. Also USP10 does not interact with Mdm2.[49]

Phosphorylation of the N-terminal end of p53 by the above-mentioned protein kinases disrupts Mdm2-binding. Other proteins, such as Pin1, are then recruited to p53 and induce a conformational change in p53, which prevents Mdm2-binding even more. Phosphorylation also allows for binding of transcriptional coactivators, like

Role in disease

If the TP53 gene is damaged, tumor suppression is severely compromised. People who inherit only one functional copy of the TP53 gene will most likely develop tumors in early adulthood, a disorder known as

The TP53 gene can also be modified by

Increasing the amount of p53 may seem a solution for treatment of tumors or prevention of their spreading. This, however, is not a usable method of treatment, since it can cause premature aging.

Certain pathogens can also affect the p53 protein that the TP53 gene expresses. One such example,

The p53 protein is continually produced and degraded in cells of healthy people, resulting in damped oscillation (see a stochastic model of this process in [58]). The degradation of the p53 protein is associated with binding of MDM2. In a negative feedback loop, MDM2 itself is induced by the p53 protein. Mutant p53 proteins often fail to induce MDM2, causing p53 to accumulate at very high levels. Moreover, the mutant p53 protein itself can inhibit normal p53 protein levels. In some cases, single missense mutations in p53 have been shown to disrupt p53 stability and function.[59]

This image shows different patterns of p53 expression in endometrial cancers on chromogenic immunohistochemistry, whereof all except wild-type are variably termed abnormal/aberrant/mutation-type and are strongly predictive of an underlying TP53 mutation:[60]

|

Suppression of p53 in human breast cancer cells is shown to lead to increased CXCR5 chemokine receptor gene expression and activated cell migration in response to chemokine CXCL13.[63]

One study found that p53 and

Experimental analysis of p53 mutations

Most p53 mutations are detected by DNA sequencing. However, it is known that single missense mutations can have a large spectrum from rather mild to very severe functional effects.[59]

The large spectrum of cancer phenotypes due to mutations in the TP53 gene is also supported by the fact that different isoforms of p53 proteins have different cellular mechanisms for prevention against cancer. Mutations in TP53 can give rise to different isoforms, preventing their overall functionality in different cellular mechanisms and thereby extending the cancer phenotype from mild to severe. Recent studies show that p53 isoforms are differentially expressed in different human tissues, and the loss-of-function or gain-of-function mutations within the isoforms can cause tissue-specific cancer or provide cancer stem cell potential in different tissues.[11][66][67][68] TP53 mutation also hits energy metabolism and increases glycolysis in breast cancer cells.[69]

The dynamics of p53 proteins, along with its antagonist

Discovery

p53 was identified in 1979 by

The TP53 gene from the mouse was first cloned by Peter Chumakov of The Academy of Sciences of the USSR in 1982,[73] and independently in 1983 by Moshe Oren in collaboration with David Givol (Weizmann Institute of Science).[74][75] The human TP53 gene was cloned in 1984[7] and the full length clone in 1985.[76]

It was initially presumed to be an

Warren Maltzman, of the Waksman Institute of Rutgers University first demonstrated that TP53 was responsive to DNA damage in the form of ultraviolet radiation.[80] In a series of publications in 1991–92, Michael Kastan of Johns Hopkins University, reported that TP53 was a critical part of a signal transduction pathway that helped cells respond to DNA damage.[81]

In 1993, p53 was voted molecule of the year by Science magazine.[82]

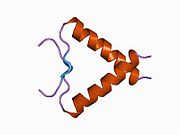

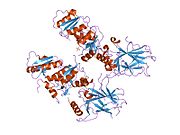

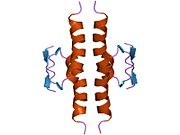

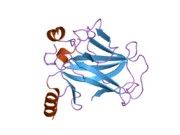

Structure

- an acidic N-terminus transcription-activation domain (TAD), also known as activation domain 1 (AD1), which activates transcription factors. The N-terminus contains two complementary transcriptional activation domains, with a major one at residues 1–42 and a minor one at residues 55–75, specifically involved in the regulation of several pro-apoptotic genes.[83]

- activation domain 2 (AD2) important for apoptotic activity: residues 43–63.

- MAPK: residues 64–92.

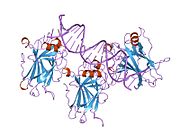

- central DNA-binding core domain (DBD). Contains one zinc atom and several arginine amino acids: residues 102–292. This region is responsible for binding the p53 co-repressor LMO3.[84]

- Nuclear Localization Signaling (NLS) domain, residues 316–325.

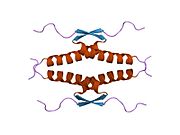

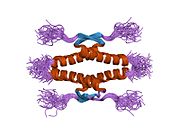

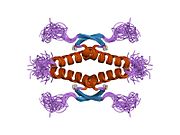

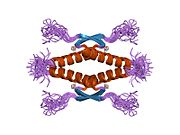

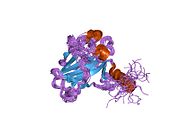

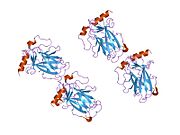

- homo-oligomerisation domain (OD): residues 307–355. Tetramerization is essential for the activity of p53 in vivo.

- C-terminal involved in downregulation of DNA binding of the central domain: residues 356–393.[85]

Mutations that deactivate p53 in cancer usually occur in the DBD. Most of these mutations destroy the ability of the protein to bind to its target DNA sequences, and thus prevents transcriptional activation of these genes. As such, mutations in the DBD are

Wild-type p53 is a

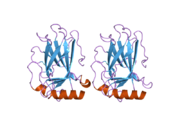

Isoforms

As with 95% of human genes, TP53 encodes more than one protein. All these p53 proteins are called the p53 isoforms.[5] These proteins range in size from 3.5 to 43.7 kDa. Several isoforms were discovered in 2005, and so far 12 human p53 isoforms have been identified (p53α, p53β, p53γ, ∆40p53α, ∆40p53β, ∆40p53γ, ∆133p53α, ∆133p53β, ∆133p53γ, ∆160p53α, ∆160p53β, ∆160p53γ). Furthermore, p53 isoforms are expressed in a tissue dependent manner and p53α is never expressed alone.[11]

The full length p53 isoform proteins can be subdivided into different protein domains. Starting from the N-terminus, there are first the amino-terminal transcription-activation domains (TAD 1, TAD 2), which are needed to induce a subset of p53 target genes. This domain is followed by the proline rich domain (PXXP), whereby the motif PXXP is repeated (P is a proline and X can be any amino acid). It is required among others for p53 mediated apoptosis.[88] Some isoforms lack the proline rich domain, such as Δ133p53β,γ and Δ160p53α,β,γ; hence some isoforms of p53 are not mediating apoptosis, emphasizing the diversifying roles of the TP53 gene.[66] Afterwards there is the DNA binding domain (DBD), which enables the proteins to sequence specific binding. The C-terminus domain completes the protein. It includes the nuclear localization signal (NLS), the nuclear export signal (NES) and the oligomerisation domain (OD). The NLS and NES are responsible for the subcellular regulation of p53. Through the OD, p53 can form a tetramer and then bind to DNA. Among the isoforms, some domains can be missing, but all of them share most of the highly conserved DNA-binding domain.

The isoforms are formed by different mechanisms. The beta and the gamma isoforms are generated by multiple splicing of intron 9, which leads to a different C-terminus. Furthermore, the usage of an internal promoter in intron 4 causes the ∆133 and ∆160 isoforms, which lack the TAD domain and a part of the DBD. Moreover, alternative initiation of translation at codon 40 or 160 bear the ∆40p53 and ∆160p53 isoforms.[11]

Due to the

Interactions

p53 has been shown to

- AIMP2,[89]

- ANKRD2,[90]

- APTX,[91]

- ATR,[92][93]

- ATF3,[97][98]

- AURKA,[99]

- BAK1,[100]

- BARD1,[101]

- BLM,[102][103][104][105]

- BRCA1,[101][106][107][108][109]

- BRCA2,[101][110]

- BRCC3,[101]

- BRE,[101]

- CEBPZ,[111]

- CDC14A,[112]

- CFLAR,[115]

- CHEK1,[102][116][117]

- CCNG1,[118]

- CREBBP,[119][120][121]

- CREB1,[121]

- Cyclin H,[122]

- CDK7,[122][123]

- DNA-PKcs,[93][116][124]

- E4F1,[125][126]

- EFEMP2,[127]

- EIF2AK2,[128]

- ELL,[129]

- EP300,[120][130][131][132]

- ERCC6,[133][134]

- GNL3,[135]

- GPS2,[136]

- GSK3B,[137]

- HSP90AA1,[138][139][140]

- HIF1A,[141][142][143][144]

- HIPK1,[145]

- HIPK2,[146][147]

- HMGB1,[148][149]

- HSPA9,[150]

- Huntingtin,[151]

- ING1,[152][153]

- ING4,[154][155]

- ING5,[154]

- IκBα,[156]

- KPNB1,[138]

- LMO3,[84]

- Mdm2,[119][157][158][159]

- MDM4,[160][161]

- MED1,[162][163]

- MAPK9,[164][165]

- MNAT1,[123]

- NDN,[166]

- NCL,[167]

- NUMB,[168]

- NF-κB,[169]

- PARC,[171]

- PARP1,[91][172]

- PIAS1,[127][173]

- CDC14B,[112]

- PIN1,[174][175]

- PLAGL1,[176]

- PLK3,[177][178]

- PRKRA,[179]

- PHB,[180]

- PML,[157][181][182]

- PSME3,[183]

- PTEN,[158]

- PTK2,[184]

- PTTG1,[185]

- RAD51,[101][186][187]

- RCHY1,[188][189]

- RELA,[169]

- Reprimo[citation needed]

- RPA1,[190][191]

- RPL11,[170]

- S100B,[192]

- SMARCA4,[195]

- SMARCB1,[195]

- SMN1,[196]

- STAT3,[169]

- TFAP2A,[199]

- TFDP1,[200]

- TIGAR,[201]

- TOP1,[202][203]

- TOP2A,[204]

- TP53BP1,[102][205][206][207][208][209][210]

- TP53BP2,[210][211]

- TOP2B,[204]

- TP53INP1,[212][213]

- TSG101,[214]

- UBE2A,[215]

- UBE2I,[127][193][216][217]

- UBC,[89][183][194][218][219][220][221][222]

- USP7,[223]

- USP10,[49]

- WWOX,[225]

- XPB,[133]

- YBX1,[90][226]

- YPEL3,[227]

- YWHAZ,[228]

- Zif268,[229]

- ZNF148,[230]

- SIRT1,[231]

- circRNA_014511.[232]

See also

- Pifithrin, an inhibitor of P53

Notes

References

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000141510 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000059552 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ PMID 24379683.

- PMID 29734785.

- ^ PMID 6396087.

- ^ S2CID 4310476.

- ^ S2CID 19647885.

- ^ PMID 3001719.

- ^ PMID 16131611.

- ISBN 978-0-87969-830-0.

- ^ Khoury MP, Bourdon JC. p53 Isoforms: An Intracellular Microprocessor? Genes Cancer. 2011 Apr;2(4):453-65. doi: 10.1177/1947601911408893. PMID: 21779513; PMCID: PMC3135639.

- PMID 10618702.

- ^ "OrthoMaM phylogenetic marker: TP53 coding sequence". Archived from the original on 2018-03-17. Retrieved 2009-12-02.

- PMID 19625214.

- PMID 21468597.

- S2CID 207372095.

- PMID 21656578.

- PMID 21316118.

- S2CID 11730631.

- S2CID 32990396.

- S2CID 23027087.

- PMID 21982800.

- ^ Gilbert SF. Developmental Biology, 10th ed. Sunderland, MA USA: Sinauer Associates, Inc. Publishers. p. 588.

- ^ National Center for Biotechnology Information (1998). "Skin and Connective Tissue". Genes and Disease. United States National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 2008-05-28.

- S2CID 4355786.

- ^ "Genome's guardian gets a tan started". New Scientist. March 17, 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-29.

- PMID 17350573.

- ^ PMID 22389628.

- PMID 18521083.

- PMID 32004494.

- PMID 22689594.

- PMID 22311782.

- PMID 19668189.

- PMID 24101460.

- S2CID 37901173.

- ^ S2CID 237506513.

- S2CID 10094554.

- PMID 22253229.

- S2CID 4357527.

- PMID 30146800.

- S2CID 4552678.

- PMID 18445702.

- PMID 32764056.

- PMID 22700930.

- PMID 19707204.

- PMID 22085928.

- ^ PMID 20096447.

- PMID 18239138.

- S2CID 38527914.

- PMID 12086865.

- S2CID 749047.

- S2CID 4373520.

- PMID 24154492.

- PMID 14704685.

- PMID 18086422.

- PMID 17928303.

- ^ PMID 9405613.

- license.

- PMID 37938166.

- PMID 18270948.

- PMID 25786345.

- PMID 27281222.

- ^ "Scientists identify drugs to target 'Achilles heel' of Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia cells". myScience. 2016-06-08. Retrieved 2016-06-09.

- ^ PMID 21779513.

- PMID 24336193.

- PMID 25754205.

- PMID 27582538.

- PMID 16773083.

- PMID 18706112.

- PMID 25433195.

- PMID 6295732.

- PMID 6296874.

- S2CID 4325094.

- PMID 4006916.

- PMID 2649981.

- PMID 2525423.

- PMID 2144364.

- PMID 6092932.

- PMID 8013425.

- PMID 8266084.

- PMID 9707426.

- ^ PMID 19995558.

- PMID 15713654.

- PMID 12367518.

- PMID 7107651.

- PMID 10982799.

- ^ PMID 18695251.

- ^ PMID 15136035.

- ^ PMID 15044383.

- ^ PMID 15159397.

- ^ PMID 10608806.

- PMID 15632067.

- S2CID 23994762.

- PMID 9135004.

- PMID 16169070.

- PMID 11792711.

- PMID 12198151.

- S2CID 43063712.

- ^ PMID 14636569.

- ^ PMID 15364958.

- PMID 11399766.

- S2CID 13084911.

- ^ PMID 12080066.

- S2CID 20898175.

- PMID 9482880.

- S2CID 7462625.

- S2CID 24616900.

- PMID 9811893.

- PMID 12534345.

- ^ PMID 10644693.

- PMID 10884347.

- PMID 11327730.

- PMID 18559494.

- ^ PMID 12756247.

- PMID 11896572.

- PMID 12556559.

- ^ PMID 12426395.

- ^ PMID 11782467.

- ^ PMID 10848610.

- ^ S2CID 6281777.

- ^ PMID 9372954.

- PMID 9679063.

- ^ PMID 12446718.

- PMID 10644996.

- ^ PMID 10380882.

- S2CID 22467088.

- PMID 10358050.

- PMID 9809062.

- PMID 15186775.

- PMID 10942770.

- ^ S2CID 38325851.

- PMID 10882116.

- PMID 12464630.

- PMID 11486030.

- PMID 12048243.

- ^ PMID 11297531.

- PMID 12427754.

- PMID 11507088.

- PMID 12606552.

- PMID 10640274.

- PMID 12124396.

- S2CID 4423081.

- PMID 12702766.

- S2CID 37789883.

- PMID 11925430.

- PMID 11106654.

- PMID 11748221.

- PMID 11900485.

- PMID 10823891.

- PMID 12208736.

- S2CID 4429461.

- ^ PMID 12750254.

- PMID 18775696.

- PMID 11799106.

- ^ PMID 12915590.

- ^ PMID 12620407.

- ^ PMID 9529249.

- PMID 12393902.

- S2CID 11794685.

- PMID 11118038.

- PMID 9444950.

- PMID 9393873.

- PMID 12384512.

- PMID 10347180.

- PMID 12138209.

- S2CID 4431258.

- ^ PMID 20546595.

- ^ PMID 14612427.

- PMID 12526791.

- PMID 9565608.

- PMID 11583632.

- PMID 12388558.

- S2CID 4311658.

- S2CID 21331603.

- PMID 11551930.

- S2CID 24106070.

- PMID 9010216.

- PMID 14500729.

- PMID 11080164.

- S2CID 13480833.

- ^ PMID 18309296.

- PMID 18206965.

- S2CID 1770399.

- PMID 8617246.

- PMID 9380510.

- PMID 12654245.

- PMID 19043414.

- S2CID 23482723.

- PMID 11751427.

- PMID 15178678.

- ^ PMID 10961991.

- ^ PMID 18583933.

- ^ PMID 11950834.

- PMID 11704667.

- PMID 1465435.

- PMID 10359315.

- PMID 12226108.

- PMID 8816502.

- PMID 16839873.

- PMID 10468612.

- PMID 11805286.

- ^ PMID 10666337.

- PMID 12110597.

- PMID 14978302.

- PMID 15611139.

- PMID 11877378.

- PMID 12351827.

- ^ PMID 8016121.

- PMID 8668206.

- PMID 12851404.

- PMID 11511362.

- PMID 11172000.

- PMID 12640129.

- PMID 8921390.

- PMID 11853669.

- PMID 18632619.

- PMID 18566590.

- PMID 18382127.

- PMID 18359851.

- S2CID 8023403.

- S2CID 4389394.

- PMID 11427532.

- PMID 11058590.

- S2CID 19222684.

- PMID 20388804.

- S2CID 26600934.

- PMID 11251186.

- PMID 11416144.

- PMID 19221490.

- PMID 30640591.

External links

- "p53 Knowledgebase". Lane Group at the Institute of Molecular and Cell Biology (IMCB), Singapore. Archived from the original on 2006-01-03. Retrieved 2008-04-06.

- GeneReviews/NCBI/NIH/UW entry on Li-Fraumeni Syndrome

- TUMOR PROTEIN p53 @ OMIM

- p53 restoration of function

- p53 @ The Atlas of Genetics and Cytogenetics in Oncology and Haematology

- TP53 Gene @ GeneCards

- p53 News provided by insciences organisation

- Goodsel DS (2002-07-01). "p53 Tumor Suppressor". Molecule of the Month. RCSB Protein Data Bank. Retrieved 2008-04-06.

- Soussi T. "p53 Web Site". Retrieved 2008-04-06.

- Living LFS A non-profit Li-Fraumeni Syndrome patient support organization

- The George Pantziarka TP53 Trust A support group from the UK for people with Li-Fraumeni Syndrome or other TP53-related disorders

- IARC TP53 Somatic Mutations database maintained at IARC, Lyon, by Magali Olivier

- PDBe-KB provides an overview of all the structure information available in the PDB for Human P53.

- scientific animation conformational changes of p53 upon binding to DNA