Pre-Pottery Neolithic B

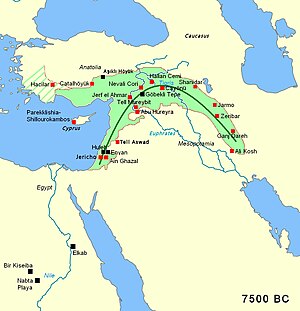

Area of the Fertile Crescent, c. 7500 BC, with main Pre-Pottery Neolithic sites. The area of Mesopotamia proper was not fully settled by humans. | |

| Geographical range | Fertile Crescent |

|---|---|

| Period | Pre-Pottery Neolithic |

| Dates | c. 10,800–8,500 BP c. 8800–6500 BC[1] |

| Type site | Jericho, Byblos |

| Preceded by | Pre-Pottery Neolithic A |

| Followed by |

|

Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) is part of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic, a Neolithic culture centered in upper Mesopotamia and the Levant, dating to c. 10,800 – c. 8,500 years ago, that is, 8800–6500 BC.[1] It was typed by British archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon during her archaeological excavations at Jericho in the West Bank.

Like the earlier

Lifestyle

Cultural tendencies of this period differ from that of the earlier Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) period in that people living during this period began to depend more heavily upon domesticated animals to supplement their earlier mixed agrarian and hunter-gatherer diet. In addition, the flint tool kit of the period is new and quite disparate from that of the earlier period. One of its major elements is the naviform core. This is the first period in which architectural styles of the southern Levant became primarily rectilinear; earlier typical dwellings were circular, elliptical and occasionally even octagonal. Pyrotechnology, the expanding capability to control fire, was highly developed in this period. During this period, one of the main features of houses is a thick layer of white clay plaster flooring, highly polished and made of lime produced from limestone.

It is believed that the use of clay plaster for floor and wall coverings during PPNB led to the discovery of

Society

Danielle Stordeur's recent work at Tell Aswad, a large agricultural village between Mount Hermon and Damascus could not validate Henri de Contenson's earlier suggestion of a PPNA Aswadian culture. Instead, they found evidence of a fully established PPNB culture at 8700 BC at Aswad, pushing back the period's generally accepted start date by 1,200 years. Similar sites to Tell Aswad in the Damascus Basin of the same age were found at Tell Ramad and Tell Ghoraifé. How a PPNB culture could spring up in this location, practicing domesticated farming from 8700 BC has been the subject of speculation. Whether it created its own culture or imported traditions from the North East or Southern Levant has been considered an important question for a site that poses a problem for the scientific community.[5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12]

Extent

Work at the site of

The culture disappeared during the

-

ʿAin Ghazal statues: closeup of one of the bicephalous statues, c. 6500 BC.

-

Ain Ghazal statue on show in theMusée du Louvre, Paris.

-

Louvre Ain Ghazal statue, frontal

Artifacts

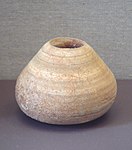

Around 8000 BC, before the invention of pottery, several early settlements became experts in crafting beautiful and highly sophisticated containers from stone, using materials such as

-

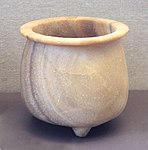

Jar in calcite alabaster, Syria, late 8th millennium BC.

-

Footed bowl in granite, Syria, end of 8th millennium BC.

-

Green aragonite tripod vase Mid-Euphrates 6000 BC Louvre Museum AO 28386

-

Calcite tripod vase, mid-Euphrates, probably from Tell Buqras, 6000 BC, Louvre Museum AO 31551

-

Alabaster pot with handles, Buqras region, 6500 BC Louvre Museum AO 28519

-

Alabaster pot Mid-Euphrates region, 6500 BC, Louvre Museum

-

Alabaster pot, Mid-Euphrates region, 6500 BC, Louvre Museum

-

Bead with human form. 8th millennium BC.

Genetics

Pre-Pottery Neolithic B fossils that were analysed for ancient DNA were found to carry the Y-DNA (paternal) haplogroups

DNA analysis has also confirmed ancestral ties between the Pre-Pottery Neolithic culture bearers and the makers of the Epipaleolithic Iberomaurusian culture of North Africa,[18] the Mesolithic Natufian culture of the Levant, the Savanna Pastoral Neolithic culture of East Africa,[19] the Early Neolithic Cardium culture of Morocco,[20] and the Ancient Egyptian culture of the Nile Valley,[21] with fossils associated with these early cultures all sharing a common genomic component.[20]

Diffusion

Carbon-14 dating

The spread of the

Analysis of mitochondrial DNA

Since the original human expansions out of Africa 200,000 years ago, different prehistoric and historic migration events have taken place in Europe.[23] Considering that the movement of the people implies a consequent movement of their genes, it is possible to estimate the impact of these migrations through the genetic analysis of human populations.[23] Agricultural and husbandry practices originated 10,000 years ago in a region of the Near East known as the Fertile Crescent.[23] According to the archaeological record this phenomenon, known as "Neolithic", rapidly expanded from these territories into Europe.[23] However, whether this diffusion was accompanied or not by human migrations is greatly debated.[23] Mitochondrial DNA – a type of maternally inherited DNA located in the cell cytoplasm- was recovered from the remains of Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) farmers in the Near East and then compared to available data from other Neolithic populations in Europe and also to modern populations from South Eastern Europe and the Near East.[23] The obtained results show that substantial human migrations were involved in the Neolithic spread and suggest that the first Neolithic farmers entered Europe following a maritime route through Cyprus and the Aegean Islands.[23]

-

Modern distribution of the haplotypes of PPNB farmers

-

Genetic distance between PPNB farmers and modern populations

Relative chronology

See also

| The Neolithic |

|---|

| ↑ Mesolithic |

| ↓ Chalcolithic |

- Holocene climatic optimum

- Levantine archaeology#Ceramics analysis

- Prehistory of the Levant

- Upper Mesopotamia#Prehistory

References

- ^ ISBN 978-1-351-80289-5.

- ^ a b Amihai Mazar (1992). Archaeology of the Land of the Bible: 10,000 – 586 BC, Doubleday: New York, p. 45.

- ^ Chris Scarre. Timeline of the Ancient World, p. 77.

- ISBN 978-0-8400-3054-2.

- ^ Helmer D.; Gourichon L., Premières données sur les modalités de subsistance dans les niveaux récents de Tell Aswad (Damascène, Syrie) – fouilles 2001-2005., 2008.

- ^ Vila, E.; Gourichon, L.; Buitenhuis, H.; et al., eds. (2008). "49". Archaeozoology of the Southwest Asia and Adjacent Areas VIII. Actes du 8e colloque de l'ASWA. Vol. 1. Lyon: Travaux de la Maison de l'Orient. pp. 119–151.

- ^ Helmer D. et Gourichon L., Premières données sur les modalités de subsistances dans les niveaux récents (PPNB moyen à Néolithique à Poterie) de Tell Aswad en Damascène (Syrie), Fouilles 2001–2005, in Vila E. et Gourichon L. (eds), ASWA Lyon June 2006., 2007.

- ^ Stordeur D. Tell Aswad. Résultats préliminaires des campagnes 2001 et 2002. Neo Lithics 1/03, 7-15, 2003.

- ^ Stordeur D. Des crânes surmodelés à Tell Aswad de Damascène. (PPNB – Syrie). Paléorient, CNRS Editions, 29/2, 109-116., 2003.

- ^ Stordeur D.; Jammous B.; Khawam R.; Morero E. L'aire funéraire de Tell Aswad (PPNB). In HUOT J.-L. et STORDEUR D. (Eds) Hommage à H. de Contenson. Syria, n° spécial, 83, 39-62., 2006.

- ^ Stordeur D., Khawam R. Les crânes surmodelés de Tell Aswad (PPNB, Syrie). Premier regard sur l’ensemble, premières réflexions. Syria, 84, 5-32., 2007.

- ^ Stordeur D., Khawam R. Une place pour les morts dans les maisons de Tell Aswad (Syrie). (Horizon PPNB ancien et PPNB moyen). Workshop Houses for the living and a place for the dead, Hommage à J. Cauvin. Madrid, 5ICAANE., 2008.

- ^ Zarins, Juris (1992) "Pastoral Nomadism in Arabia: Ethnoarchaeology and the Archaeological Record," in O. Bar-Yosef and A. Khazanov, eds. "Pastoralism in the Levant"

- ^ "Metropolitan Museum of Art". metmuseum.org.

- ^ PMID 24901650.

- ISBN 9788468964799. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- PMID 29545507.

- PMID 28938123.

- ^ S2CID 214727201.

- PMID 28556824.

- ^ PMID 24806472..

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Material was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License - ^ PMID 24901650.

External links

![]() Media related to Pre-Pottery Neolithic B at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pre-Pottery Neolithic B at Wikimedia Commons