Paço de São Cristóvão

| Paço de São Cristóvão | |

|---|---|

Ruin | |

| Material | Brick, Stucco |

| Lifts/elevators | 0 |

| Grounds | 5920 m² |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Pedro José Pezerát |

| Services engineer | Concrejato |

| Known for | Museum |

National Historic Heritage of Brazil | |

| Designated | 99 |

| Reference no. | 1938 |

Paço de São Cristóvão (Portuguese pronunciation:

History

Background

1892–present

In the 16th and 17th centuries, the area where the palace is currently located was part of a

Royal residence

Prince Regent John and his family had been living in the Paço Imperial since their arrival in Rio de Janeiro in 1808. The prince regent felt very honored by Elias's gift of the best house in Rio and rewarded Elias with another property, not quite as grand. He began transforming the manor into a royal residence. At the time, the area of the farm was still surrounded by mangroves and communication by land with the city was difficult. Later, the wetlands were drained and the roads improved.

To better accommodate the royal family, the manor house, though vast and comfortable, needed to be adapted. The most important renovation was begun at the time of the nuptials of Prince Pedro with the Archduchess Maria Leopoldina of Austria, in 1819, and finished 1821. The renovation was directed by English architect John Johnston. In front of the palace, Johnston installed a decorative portico, a gift sent from England to Brazil by Hugh Percy, 2nd Duke of Northumberland. The gate, inspired by Robert Adams' porch for the "Sion House", the nobleman's residence in England, is shaped in "Coade stone" manufactured by the English company Coade & Sealy.

The architectural line of the palace is similar to that of the

Imperial residence

After the declaration of

After the marriage of Pedro I and

Republican period

In 1891, the building was used by Brazilian politicians writing the first Republican Constitution of the country.

In 1892, the director of the National Museum of Rio de Janeiro managed to transfer the institution from the Campo de Santana to the palace. The inner decoration of the palace was dispersed, but part of it can still be found in other museums, like the Imperial Museum of Petrópolis, in which the Throne Room was reassembled.

National Museum

Founded in 1818 by

Much of the art collection displayed by the museum still consisted of what was gathered by Emperor Pedro II himself. In this manner, it reflects 19th-century views of anthropology, archeology and sciences in general.

Visitors could also see a few rooms of the ancient palace with its original painted and

On 2 September 2018, the palace was devastated by an extensive fire. The damage to heritage assets have been reported to be "incalculable". One of the few known surviving major artifacts is the Bendegó meteorite.[5][6][7] After the fire, a metallic roof covering 5,000 m2 upper the debris was built.[8]

Gallery

Historic timeline of construction

-

Palace in the early 19th century, before the Neoclassical intervention

-

Painting of the Imperial Palace (1835–1840)

-

Antique illustration of the palace, by Jean-Baptiste Debret (1768–1848)

-

1858–1861

-

The Palace in the end of the 19th century

-

Emperor Pedro I's coffin arrives at the palace for exposition, 1972

-

The Imperial Palace after the Neoclassical intervention. Old pink paint

-

The palace in flames during the night of 2 September 2018, leaving it inruin

Exterior before the 2018 fire

-

Gates of the former main entrance

-

Imperial coat of arms

-

View from parking lot

-

Facade

-

The palace seen from the garden

-

Side front view

-

Central view

-

One of the many doors

-

Detail of a door bearing theimperial cypherof Emperor Pedro II

Interior before the 2018 fire

-

Ceiling detail

-

Internal details

-

Walls and ceiling

-

Ceiling

-

Ceiling

-

Ceiling

-

Ceiling

-

Ceiling

-

Ceiling

-

Room

-

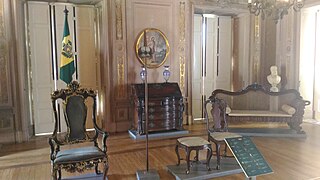

Throne of King John VI

-

The former Throne Room

-

Throne Room details and a bust of Emperor Pedro II. On the wall at the right side of the picture, a portrait of King John VI

Grounds

-

Statue of Empress Maria Leopoldina with two of her children

-

Monument to Emperor Pedro II in front of the palace

-

Canto das Sereias sculpture by Nicolina Vaz de Assis

-

Quinta's bandstand, known as the Chinese pagoda

-

"Temple of Apollo" after restoration work in 2022

-

Street

-

Frontal garden before restoration work

-

Internal garden before restoration work

-

Garden fountain

-

Bird's-eye view

-

Quinta da Boa Vista park lake

-

Lake and the palace in the background

-

Palace grounds

-

Kayaking

-

The palace rear and trees before the 2018 fire.

-

Vegetation

-

Fire-damaged facade of the palace completely restored, September 2022. View from the new garden

Investigations

The fire that destroyed the National Museum began in the

See also

- Paço Imperial, the seat of the Imperial government

- Quinta da Boa Vista

- National Museum of Brazil

References

- ^ "Museu Nacional Fire in Rio de Janeiro Natural History". G1. Archived from the original on September 3, 2018. Retrieved 2018-09-07.

- ^ "Incêndio de grandes proporções destrói o Museu Nacional, na Quinta da Boa Vista". G1. Retrieved 2018-09-02.

- ^ "Genealogia Fluminense – Cantagalo". www.genealogiabrasileira.com. Retrieved 2016-09-29.

- ^ "Prédio do Museu Nacional preocupava Senado do Império". www12.senado.leg.br (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2018-10-01.

- ^ "Bendegó: el meteorito que resistió las llamas del incendio del Museo Nacional de Brasil". BioBioChile - La Red de Prensa Más Grande de Chile (in Spanish). 3 September 2018. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ^ Phillips, Dom (3 September 2018). "Brazil museum fire: 'incalculable' loss as 200-year-old Rio institution gutted". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ^ Phillips, Dom (3 September 2018). "'200 years of knowledge lost': fire engulfs Brazil's national museum". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ^ "Museu Nacional é liberado para ações de prevenção e estabilização". UOL (in Portuguese). 14 September 2018. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- ^ "Incêndio que destruiu o Museu Nacional começou no ar-condicionado do auditório, diz laudo da PF". G1 (in Portuguese). 4 April 2019. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- Quinta da Boa Vista e Paço de São Cristóvão Rio de Janeiro Aqui. Retrieved on 2009-07-04. (in Portuguese)

External links

- National Museum of Brazil official website (in Portuguese)