Paclitaxel

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Taxol, Abraxane, others |

| Other names | PTX |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a607070 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Intravenous |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 6.5% (by mouth)[3] |

| Protein binding | 89 to 98% |

| Metabolism | Liver (CYP2C8 and CYP3A4) |

| Elimination half-life | 5.8 hours |

| Excretion | Fecal and urinary |

| Identifiers | |

| |

JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Paclitaxel, sold under the brand name Taxol among others, is a

Common side effects include

Paclitaxel was isolated in 1971 from the

Medical use

Paclitaxel is approved in the UK for ovarian, breast, lung, bladder, prostate, melanoma, esophageal, and other types of solid tumor cancers as well as Kaposi's sarcoma.[10]

It is recommended in

As of 2018[update], it is approved in the United States for the treatment of breast, pancreatic, ovarian, Kaposi's sarcoma and non-small-cell lung cancers.[12][13]

Similar compounds

Albumin-bound paclitaxel (brand name

Synthetic approaches to paclitaxel production led to the development of docetaxel. Docetaxel has a similar set of clinical uses to paclitaxel, and it is marketed under the brand name Taxotere.

Restenosis

Paclitaxel is used as an antiproliferative agent for the prevention of restenosis (recurrent narrowing) of coronary and peripheral stents; locally delivered to the wall of the artery, a paclitaxel coating limits the growth of neointima (scar tissue) within stents.[19] Paclitaxel drug-eluting stents for coronary artery placement are sold under the trade name Taxus by Boston Scientific in the United States. Paclitaxel drug-eluting stents for femoropopliteal artery placement are also available.

Side effects

Common side effects include nausea and vomiting,

Dexamethasone is given prior to paclitaxel infusion to mitigate some of the side effects.[21]

A number of these side effects are associated with the excipient used, Cremophor EL, a polyoxyethylated castor oil. Allergies to cyclosporine, teniposide, and other drugs delivered in polyoxyethylated castor oil may increase the risk of adverse reactions to paclitaxel.[22]

Mechanism of action

Paclitaxel is one of several

The ability of paclitaxel to inhibit spindle function is generally attributed to its suppression of microtubule dynamics,[25] but other studies have demonstrated that suppression of dynamics occurs at concentrations lower than those needed to block mitosis. At the higher therapeutic concentrations, paclitaxel appears to suppress microtubule detachment from centrosomes, a process normally activated during mitosis.[26] Paclitaxel binds to the beta-tubulin subunits of microtubules.[27]

Chemistry

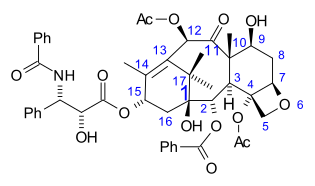

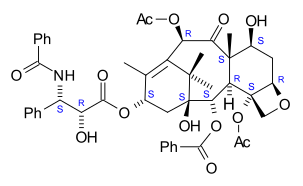

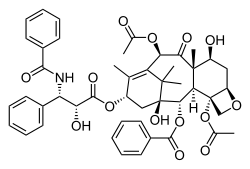

The

Production

Bark processing

From 1967 to 1993, almost all paclitaxel produced was derived from bark of the Pacific yew, Taxus brevifolia, the harvesting of which kills the tree in the process.[28] The processes used were descendants of the original isolation method of Monroe Wall and Mansukh Wani; by 1987, the U.S. National Cancer Institute (NCI) had contracted Hauser Chemical Research of Boulder, Colorado, to handle bark on the scale needed for phase II and III trials.[citation needed] While both the size of the wild population of the Pacific yew and the magnitude of the eventual demand for paclitaxel were uncertain, it was clear that an alternative, sustainable source of the natural product would be needed. Initial attempts to broaden its sourcing used needles from the tree, or material from other related Taxus species, including cultivated ones,[citation needed] but these attempts were challenged by the relatively low and often highly variable yields obtained. Early in the 1990s, coincident with increased sensitivity to the ecology of the forests of the Pacific Northwest, paclitaxel was successfully extracted on a clinically useful scale from these sources.[29]

Semisynthesis

Concurrently, synthetic chemists in the U.S. and France had been interested in paclitaxel, beginning in the late 1970s.[

The view of the NCI, however, was that even this route was not practical.[

As of 2013, BMS was using the semisynthetic method utilizing needles from the European yew to produce paclitaxel.

In 1993, paclitaxel was discovered as a natural product in Taxomyces andreanae, a newly described

Biosynthesis

Taxol is a tetracyclic

Total synthesis

By 1992, at least thirty academic research teams globally were working to achieve a

As of 2006, five additional research groups had reported successful total syntheses of paclitaxel:

While the "political climate surrounding [paclitaxel] and [the Pacific yew] in the early 1990s ... helped bolster [a] link between total synthesis and the [paclitaxel] supply problem," and though total synthesis activities were a requisite to explore the

History

The discovery of paclitaxel began in 1962 as a result of a NCI-funded screening program.[8] A number of years later it was isolated from the bark of the Pacific yew, Taxus brevifolia, hence its name "taxol".[8]

The discovery was made by

Plant screening program

In 1955, the NCI in the United States set up the Cancer Chemotherapy National Service Center (CCNSC) to act as a public screening center for anticancer activity in compounds submitted by external institutions and companies.[51] Although the majority of compounds screened were of synthetic origin, one chemist, Jonathan Hartwell, who was employed there from 1958 onwards, had experience with natural product derived compounds, and began a plant screening operation.[52] After some years of informal arrangements, in July 1960, the NCI commissioned the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) botanists to collect samples from about 1,000 plant species per year.[53] On 21 August 1962, one of those botanists, Arthur S. Barclay, collected bark from a single Pacific yew tree in a forest north of the town of Packwood, Washington, as part of a four-month trip to collect material from over 200 different species. The material was then processed by a number of specialist CCNSC subcontractors, and one of the tree's samples was found to be cytotoxic in a cellular assay on 22 May 1964.[54]

Accordingly, in late 1964 or early 1965, the fractionation and isolation laboratory run by Monroe E. Wall in Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, began work on fresh Taxus samples, isolating the active ingredient in September 1966 and announcing their findings at an April 1967 American Chemical Society meeting in Miami Beach.[55] They named the pure compound taxol in June 1967.[54] Wall and his colleague Wani published their results, including the chemical structure, in 1971.[56]

The NCI continued to commission work to collect more Taxus bark and to isolate increasing quantities of taxol. By 1969, 28 kg (62 lb) of crude extract had been isolated from almost 1,200 kg (2,600 lb) of bark, although this ultimately yielded only 10 g (0.35 oz) of pure material,[57] but for several years, no use was made of the compound by the NCI. In 1975, it was shown to be active in another in vitro system; two years later, a new department head reviewed the data and finally recommended taxol be moved on to the next stage in the discovery process.[58] This required increasing quantities of purified taxol, up to 600 g (21 oz), and in 1977 a further request for 7,000 lb (3,200 kg) of bark was made.

In 1978, two NCI researchers published a report showing taxol was mildly effective in leukaemic mice.

Early clinical trials, supply and the transfer to BMS

Phase I clinical trials began in April 1984, and the decision to start Phase II trials was made a year later.[62] These larger trials needed more bark and collection of a further 12,000 pounds was commissioned, which enabled some phase II trials to begin by the end of 1986. But by then it was recognized that the demand for taxol might be substantial and that more than 60,000 pounds of bark might be needed as a minimum. This unprecedentedly large amount brought ecological concerns about the impact on yew populations into focus for the first time, as local politicians and foresters expressed unease at the program.[63]

The first public report from a phase II trial in May 1988 showed promising effects in melanoma and refractory ovarian cancer.[64] At this point, Gordon Cragg of the NCI's Natural Product Branch calculated the synthesis of enough taxol to treat all the ovarian cancer and melanoma cases in the US would require the destruction of 360,000 trees annually. For the first time, serious consideration was given to the problem of supply.[63] Because of the practical and, in particular, the financial scale of the program needed, the NCI decided to seek association with a pharmaceutical company, and in August 1989, it published a

Although the offer was widely advertised, only four companies responded to the CRADA, including the American firm

In 1990, BMS applied to trademark the name taxol as Taxol(R). This was controversially approved in 1992. At the same time, paclitaxel replaced taxol as the generic (

Society and culture

Legal status

Paclitaxel was approved for medical use in the European Union in 2008.[70]

In November 2023, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use of the European Medicines Agency adopted a positive opinion, recommending the granting of a marketing authorization for the medicinal product Naveruclif, intended for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer, metastatic adenocarcinoma of the pancreas and non-small cell lung cancer.[70] The applicant for this medicinal product is Accord Healthcare S.L.U.[70]

Economics

As of 2006[update], the cost to the NHS per patient in early breast cancer, assuming four cycles of treatment, was about £4,000 (approx. $6,000).[71]

Research

This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: Huge paragraph needs to be split and sorted. (September 2023) |

Caffeine has been speculated to inhibit paclitaxel-induced apoptosis in colorectal cancer cells.[72]

Aside from its direct clinical use, paclitaxel is used extensively in biological and biomedical research as a

In 2016 in vitro multi-drug resistant mouse tumor cells were treated with paclitaxel encased in exosomes. Doses 98% less than common dosing had the same effect. Also, dye-marked exosomes were able to mark tumor cells, potentially aiding in diagnosis.[79][80]

Additional images

-

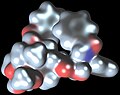

Space-filling model of paclitaxel

-

Rotating paclitaxel molecule model

-

Crystal structure of paclitaxel

-

Total charge surface of taxol. Minimum energy conformation.

References

- ^ "Paclitaxel Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 24 January 2019. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- S2CID 231917.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Paclitaxel". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 14 September 2017. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- PMID 22907122.

- ISBN 9780387310565. Archivedfrom the original on 21 December 2016.

- ISBN 9783527607495. Archivedfrom the original on 21 December 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Taxol® (NSC 125973)". National Cancer Institute. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 14 February 2016. Wayback machine

- hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- S2CID 44624033. Archived from the originalon 26 June 2019. Retrieved 28 October 2018.

- ^ "British National Formulary". Archived from the original on 14 March 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2007.

- ^ "Paclitaxel, Protein-Bound Suspension". Paclitaxel, Protein-Bound Suspension. Cancer.Org. 6 January 2015. Retrieved 24 January 2015.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Product Information: TAXOL(R) IV injection, paclitaxel IV injection. Bristol-Myers Squibb Company, Princeton, NJ, 2013. Accessed from https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2015/020262s051lbl.pdf Archived 10 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine on 4 October 2018.

- PMID 11527683.

- ^ "Abraxane Drug Information Archived 2005-05-26 at the Wayback Machine." Food and Drug Administration. 7 January 2005. Retrieved on 9 March 2007.

- ^ Product Information: ABRAXANE(R) intravenous injection suspension, paclitaxel protein-bound particles intravenous injection suspension. Celgene Corporation (per FDA), Summit, NJ, 2018. Accessed from https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2018/021660s045lbl.pdf Archived 26 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine on 4 October 2018.

- PMID 18163585.

- PMID 36227807.

- PMID 11342479.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-118-68285-2.

- ISBN 978-0-7817-4689-2.

- ^ ""Paclitaxel Injection". Medline Plus. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 12 February 2010.

- S2CID 11114877.

- PMID 18710927.

- S2CID 10228718.

- PMID 20978163.

- from the original on 22 January 2021. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- ^ Gersmann H, Aldred J (10 November 2011). "Medicinal tree used in chemotherapy drug faces extinction". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 February 2017. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- ^ Goodman & Walsh 2001, pp. 172–5.

- ^ Goodman & Walsh 2001, pp. 100–1.

- ISBN 978-0-13-873736-8.

- PMID 29468872.

- ^ "Paclitaxel Injection, USP" (PDF). Injectable Pharmaceuticals. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ "History". Archived from the original on 24 May 2016. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ "Phyton BioTech Paclitaxel". Archived from the original on 7 August 2016. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ISBN 978-3-527-33547-3.

- ^ Gilbert Gorr and Roland Franke. Commercial Pharmaceutical Production of Complex APIs via Plant Cell Fermentation (PCF®) Technology. Presentation at CPhI 2015, 13 Oct..

- ^ "2004 Greener Synthetic Pathways Award: Bristol-Myers Squibb Company: Development of a Green Synthesis for TAXOL Manufacture via Plant Cell Fermentation and Extraction". Archived from the original on 2 October 2006.

- PMID 8097061.

- S2CID 260283080.

- (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-470-74276-1.

- PMID 24614567.

- PMID 20622989.

- ^ PMID 12703766.

- Chemical and Engineering News(C&EN), 21 February 1994, page 32, and primary citations appearing at Holton and Nicolaou taxol total synthesis articles.

- ^ PMID 7906053.

- ^ Goodman & Walsh 2001, pp. 179–182.

- from the original on 24 November 2016.

- PMID 8820947.

- ^ Goodman & Walsh 2001, p. 17.

- ^ Goodman & Walsh 2001, p. 22.

- ^ Goodman & Walsh 2001, pp. 25, 28.

- ^ a b Goodman & Walsh 2001, p. 51.

- PMID 7850785.

- PMID 5553076.

- ^ Goodman & Walsh 2001, p. 81.

- ^ Goodman & Walsh 2001, pp. 79, 81.

- ^

Fuchs DA, Johnson RK (August 1978). "Cytologic evidence that taxol, an antineoplastic agent from Taxus brevifolia, acts as a mitotic spindle poison". Cancer Treatment Reports. 62 (8): 1219–1222. PMID 688258.

- ^ Goodman & Walsh 2001, p. 95.

- ^ a b Goodman & Walsh 2001, p. 97

- ^ Goodman & Walsh 2001, p. 115.

- ^ a b c d Goodman & Walsh 2001, p. 120

- ^ Rowinsky EK, Donehower RC, Rosenshein NB, Ettinger DS, McGuire WP (1988). "Phase II study of taxol in advanced epithelial malignancies". Proceedings of the Association of Clinical Oncology. 7: 136.

- ^ "Technology Transfer: NIH-Private Sector Partnership in the Development of Taxol" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 July 2007. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- ^ Nader R, Love J (February 1993). "Looting the medicine chest: how Bristol-Myers Squibb made off with the public's cancer research". The Progressive. Archived from the original on 24 September 2004.

- S2CID 31510966.

- ^ Goodman & Walsh 2001, p. 170.

- ^ Bristol-Myers Squibb, The development of TAXOL (paclitaxel), March 1997, as cited in Goodman & Walsh 2001, p. 2

- ^ "NICE Guidance TA108". 27 September 2006. Archived from the original on 30 June 2007.

- from the original on 22 June 2015.

- PMID 24535601.

- PMID 29352977.

- S2CID 45994154.

- PMID 18923545.

- ^ MS Society of Canada Phase II Clinical trial of Micellar Paclitaxel for secondary-progressive MS underway in Canada Archived 15 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ MS Society of Canada Angiotech Halts Study of Micellar Paclitaxel stating no benefit of statistical significance seen Archived 15 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lavars N (14 January 2016). "Cloaking chemo drugs in cellular bubbles destroys cancer with one fiftieth of a regular dose". www.gizmag.com. Archived from the original on 24 February 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- PMID 26586551.

Further reading

- Jordan G, Vivien W (5 March 2001). The Story of Taxol: Nature and Politics in the Pursuit of an Anti-Cancer Drug. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-56123-5. Archivedfrom the original on 14 January 2023. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

External links

- "Paclitaxel". National Cancer Institute. 5 October 2006.

- "Paclitaxel". NCI Drug Dictionary. 2 February 2011.

- Molecule of the Month: TAXOL by Neil Edwards, University of Bristol.

- A Tale of Taxol from Florida State University.

- Berenson A (1 October 2006). "Hope, at $4,200 a Dose". The New York Times. Retrieved 31 March 2007.