Palace Theatre (New York City)

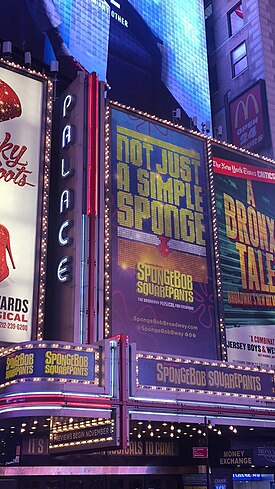

The SpongeBob Musical, 2017 | |

| |

| Address | 1564 Broadway Manhattan, New York City United States |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°45′32″N 73°59′05″W / 40.758842°N 73.984728°W |

| Owner | Nederlander Organization and Stewart F. Lane |

| Operator | Nederlander Organization |

| Type | Broadway theatre |

| Capacity | 1,743[a] |

| Current use | Closed for renovation |

| Construction | |

| Opened | March 24, 1913 (vaudeville) January 29, 1966 (Broadway theater) |

| Rebuilt | 1987–1991, 2018–2022 |

| Years active | 1913–1932 (vaudeville) 1932–1965 (movie palace) 1966–present (Broadway) |

| Architect | Kirchhoff & Rose |

| Website | |

| broadwaydirect | |

New York City Landmark | |

| Designated | July 14, 1987[1] |

| Reference no. | 1367[1] |

| Designated entity | Auditorium interior |

The Palace Theatre is a

The modern Palace Theatre consists of a three-level

The Palace was most successful as a vaudeville house in the 1910s and 1920s. Under RKO Theatres, it became a movie palace called the RKO Palace Theatre in the 1930s, though it continued to host intermittent vaudeville shows in the 1950s. The Nederlander Organization purchased the Palace in 1965 and reopened the venue as a Broadway theater the next year. The theater closed for an extensive renovation from 1987 to 1991, when the original building was partly demolished and replaced with the DoubleTree Suites Times Square Hotel; the theater was reopened within the DoubleTree in 1991. The DoubleTree Hotel was mostly demolished in 2019 to make way for the TSX Broadway development. As part of this project, the Palace closed again in 2018 and was lifted 30 feet (9.1 m) in early 2022. As of 2023[update], the renovation is scheduled to be completed in 2024.

Buildings

The Palace Theatre is at 1568 Broadway, at the southeast corner of Seventh Avenue and 47th Street, in the Theater District of Midtown Manhattan in New York City. It faces Duffy Square, the northern end of Times Square. The theater's site abuts the I. Miller Building and Embassy Theatre to the south.[2]

The Palace Theatre was designed by Milwaukee architects Kirchhoff & Rose and was completed in 1913.[2] The theater was funded by Martin Beck, a vaudeville entrepreneur.[3][4] The theater has been housed in three buildings over the years. While the interior space dates to the 1913 design by Kirchhoff & Rose, the original theater building was partly demolished in 1988[5][6] and the theater space was renovated inside the DoubleTree Suites Times Square Hotel, completed between 1990 and 1991.[2] The DoubleTree Hotel was itself demolished in 2019 to make way for the TSX Broadway development.[7][8]

Original building

The Palace Theatre was originally composed of an office wing along Times Square, as well as the theater wing on 47th Street that contained the auditorium.[9][10] The original building's site was assembled from ten land lots at 1564–1566 Broadway and 156–170 West 47th Street, which were arranged in an "L" shape.[11][12] The Broadway lots collectively measured 40 by 80 feet (12 by 24 m), while the 47th Street lots measured 137 by 100 feet (42 by 30 m).[9][13] This structure was designed by Kirchhoff & Rose, with James J. F. Gavigan as an associate architect. The steelwork was constructed by the George A. Just Company.[10][14]

The office wing was an 11-story[9][15] or 12-story structure, which served as the theater's main entrance.[10][14] In the original building's later years, the entrance had a marquee.[15] The office wing had an ornate marble facade, as well as two public elevators and a private one inside.[9] The theater entrance was 40 feet (12 m) wide and contained an outer lobby with either Pavanazzo[15][16] or yellow Carrara marble[17] and a Siena-marble inner lobby.[15][16][17] The lobbies were accessed by two sets of stained-glass, bronze-framed screen doors.[15][16] There were stairs to the upper floors in the inner lobby. Past the two lobbies was a foyer that led directly to the auditorium (see Palace Theatre (New York City) § Auditorium).[18]

The theater wing measured 88 by 125 feet (27 by 38 m).[10][14] It had a brick or terracotta facade on 47th Street.[9][15] The interior had French decorations.[9] The auditorium originally had a seating capacity of 1,820, with double balcony levels and 20 boxes arranged in tiers.[19] It was characterized as having an ivory-and-bronze color scheme.[15][16][17] Five massive girders spanned the auditorium; each measured 86 feet (26 m) long and 8 feet (2.4 m) deep, weighing 30 short tons (27 long tons; 27 t).[10][14] There were also 32[16] or 36 dressing rooms.[9]

DoubleTree Suites

An

The theater's lobby, as well as the hotel's entrance and some retail shops, were on the ground story.[21][29] The entrance to the theater was at approximately the same location as in the original building,[26] and the lobby from the old office wing was preserved.[24] The theater lobby was divided into two sections leading into a foyer.[30] Above that was a five-story atrium with some of the hotel's public spaces, which were placed between the beams,[21][24][29] and 36 guestroom stories.[21] A 12-foot-wide (3.7 m) emergency exit[29] was preserved on the eastern side of the theater.[29][30] Within the theater itself, mezzanine restrooms, an air-conditioning system, and an elevator to the second balcony were installed.[31] Furthermore, the backstage facilities were enlarged.[24][31] The Palace Theatre's original facade on 47th Street, consisting of rusticated limestone blocks at the first floor and brick on the upper stories, still remained but was not protected as a New York City landmark.[32] The theater's lobby was also not protected as a landmark.[33]

TSX Broadway

During the late 2010s and early 2020s, the DoubleTree/Palace site was redeveloped as part of TSX Broadway, a $2 billion mixed-use structure with a 669-room hotel, which was built around, above, and below the Palace's auditorium.[34][35] The new structure retains the lowest 16 stories of the DoubleTree structure.[36][37][33] The area occupied by the 1987 lobby was replaced with retail space, extending three levels below ground. This required the auditorium to be raised by about 30 feet (9.1 m).[37][35][36][c] The auditorium is supported by columns that, in turn, rest on caissons extending 45 feet (14 m) deep.[40]

About 10,000 square feet (930 m2) of

Auditorium

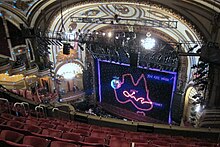

The auditorium, which the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) has protected as a city landmark,[47][48] is the only portion of the original theater that survives.[2][48] It is placed in a rigid enclosure that is structurally separate from the buildings within which it has been housed.[39][42] The auditorium has boxes, two balconies above an orchestra level, and a large stage behind an oversized proscenium arch. The auditorium's width is slightly greater than its depth. The foyer and lobby were designed with plaster decorations in high relief, which alluded to the vaudeville presented at the Palace, while the stage itself was originally sloped.[15] Though the auditorium's orchestra level was originally at the ground story,[48] it was raised to the third story when TSX Broadway was built.[36]

Seating areas

Prior to its closure in 2018, the auditorium had 1,743 seats.[49][50][51][a] The orchestra level has a raked floor that slopes downward toward the stage. Both balcony levels have curved fronts and cantilever above the orchestra, sloping downward toward the stage.[53] All three levels contain promenades, which have cornices on their ceilings. Staircases behind each promenade connect the three levels of seating.[54]

The first balcony level extends half the depth of the orchestra and contains two staircases about halfway through.[53] The front of the balcony has decorative moldings with classical masks, while its underside contains plaster moldings of ropes.[55] The second balcony contains rope moldings on its underside, which form a rectangular pattern. The front edge of the second balcony's underside contains guilloche moldings interspersed with oak branches, above which are decorative moldings with masks. The second balcony's side walls have decorative pilasters that support a frieze, as well as exit doors with curved pediments.[56] The ceiling of the second balcony has ventilation grates, which are not part of the original design.[57][58]

The orchestra level has boxes on either side, divided by white-marble barriers with black-marble baseboards.

Other design features

The proscenium arch measures 44 feet (13 m) across.[15][16] It contains pellet, egg-and-dart, and acanthus-leaf moldings surrounding a band of acanthus leaves. The top of the arch consists of a keystone with a molding of a child's head.[55] A sounding board rises above the proscenium arch, with foliate bands at the perimeter. At the center of the sounding board, above the stage, is a circular panel depicting a lyre.[54] The orchestra pit is at the front of the orchestra seating level, in front of the proscenium. It dates from a 1965 renovation and contains high walls.[54] The stage is behind the proscenium arch and orchestra pit.[53] The stage historically had a Wurlitzer Opus 303 organ.[3][60]

History

The vaudevillian Martin Beck was the operator of the Orpheum Circuit, which in the early 20th century was the dominant vaudeville circuit on the West Coast of the United States. Its East Coast complement was the Keith–Albee circuit, composed of Benjamin Franklin Keith and Edward Albee, who operated venues both by themselves and through their United Booking Office.[61][62] The Orpheum and Keith–Albee circuits had proposed a truce in 1906, wherein Orpheum would control vaudeville west of Chicago and Keith–Albee would control vaudeville east of Chicago, including New York City.[62] This truce was implemented in 1907.[63]

Development

Beck and Herman Fehr announced in December 1911 that they had leased the site with plans to construct a venue, the Palace Theatre.[11][12][13] Beck's representatives initially said the Palace would not be part of the Orpheum interests and, therefore, would not be used to show vaudeville.[11] Beck subsequently recanted, saying he would use the Palace for vaudeville.[64] In February 1912, Kirchhoff & Rose and Gavigan filed plans with the New York City Department of Buildings for a theater building at Broadway and 47th Street.[65]

Due to the truce between Orpheum and Keith–Albee, Edward Albee initially said any vaudeville act that played the Palace would not be allowed on the Keith–Albee circuit.[66] Albee demanded that Beck turn over three-quarters ownership to use acts from the Keith–Albee circuit, to which Beck acquiesced.[64][67][68][d] Albee moved the B. F. Keith office to the fifth floor,[69][70] and the UBO office moved to the office wing as well.[68] Furthermore, Willie Hammerstein held the exclusive franchise to vaudeville performances around Times Square.[68][71] Because of the vaudeville restriction, Werba & Luescher obtained an option on the new theater in mid-1912.[71][72] Hammerstein initially refused to sell his exclusive vaudeville franchise to Albee,[73] but Hammerstein agreed to a $200,000 settlement in May 1913, after the theater had opened.[74] The Palace's programming was still unknown to the public until February 1913, when The New York Times announced the theater would be "something along the lines of English music halls", with events such as ballets, rather than "strict vaudeville".[75]

Vaudeville

The theater finally opened on March 24, 1913, with headliner Ed Wynn.[76][77] Tickets cost $1.50 for matinees and $2.00 for nighttime performances. The screenwriter Marian Spitzer wrote of opening day: "The theatre itself, living up to advance publicity, was spacious, handsome and lavishly decorated in crimson and gold. But nothing happened that afternoon to suggest the birth of a great theatrical tradition."[78] Rather, the public mostly considered its $2 admission fees to be expensive.[79] The media widely mocked the opening bill;[77] four days after the Palace opened, Variety magazine printed an article entitled "Palace $2 Vaudeville a Joke: Double-Crossing Boomerang".[66][80] Also problematic was the presence of Hammerstein's Victoria Theatre, a much more successful and established vaudeville venue.[81] The Variety article noted that, while the Victoria had played to capacity two days in a row, the Palace had to give out free coupons to half the guests and still struggled to fill the balcony seats.[80]

The Palace's first success was the one-act play Miss Civilization, featuring Ethel Barrymore, six weeks after the theater opened.[78] It was only after an appearance by French actress Sarah Bernhardt on May 5, 1913, that the Palace became popular.[82] Except for a period from May to December 1913, the Palace had performances every day for the next two decades.[83] By December 1914, Variety was characterizing the Palace as "the greatest vaudeville theater in America, if not the world".[84][85] The death of Willie Hammerstein the same year, and the subsequent closure of the Victoria, contributed to the Palace's popularity.[68] Keith also died in 1914, giving Albee even more control of the Palace.[64][68] Albee sometimes traded on the performers' desire for this goal by forcing acts to accept smaller profits.[68][84] To "play the Palace" meant that entertainers had reached the pinnacles of their vaudeville careers.[3][68][84] The theater itself was nicknamed the "Valhalla of Vaudeville".[68][86] Performer Jack Haley wrote:

Only a vaudevillian who has trod its stage can really tell you about it ... only a performer can describe the anxieties, the joys, the anticipation, and the exultation of a week's engagement at the Palace. The walk through the iron gate on 47th Street through the courtyard to the stage door, was the cum laude walk to a show business diploma. A feeling of ecstasy came with the knowledge that this was the Palace, the epitome of the more than 15,000 vaudeville theaters in America, and the realization that you have been selected to play it. Of all the thousands upon thousands of vaudeville performers in the business, you are there. This was a dream fulfilled; this was the pinnacle of Variety success.[87]

A typical bill would have nine acts, who would perform twice a day. The bills were rotated every Monday. Consequently, the Monday matinee was generally considered among vaudevillians to be the most important of any given week, with the harshest audience.[66] A failed act would generally be eliminated from the evening shows.[66][83] Because of the constant rotations of acts, Variety observed in 1914 that the theater was "using up headliners at an alarming rate".[85] At its peak, the Palace's annual profit was $500,000,[69][83] and the average bill was paid $12,000.[69] About three-quarters of revenue was from subscriptions, and many patrons who regularly visited the Monday afternoon shows were subscription holders.[66] Performing comedians would select "stooges" from the Palace's box seats. The audience members in the right-side first-balcony boxes would generally assist the performers.[88][89]

Vaudeville headliners

Throughout vaudeville's heyday, the headliners (usually billed next to the closing act) included:

- Ed Wynn (1913)[76][77]

- Ethel Barrymore (1913)[90]

- Nora Bayes (1914)[91]

- Fritzi Scheff (1914)[77]

- Nan Halperin (1915)[92]

- Will Rogers (1916)[93]

- Blossom Seeley (1917)[94]

- Lillian Russell (1918)[95]

- Leon Errol (1919)[96]

- Marie Cahill (1919)[97]

- Olga Petrova (1919)[98]

- The "Dixie Duo" (Noble Sissle and Eubie Blake) (1919)[99]

- Bert Williams (1919)[100]

- Marie Dressler (1919)[101]

- Aileen Stanley (1920, 1926, 1930, 1931)[102]

- The Marx Brothers (1920)[103]

- Lou Clayton and Cliff Edwards (1921)[104]

- Bessie Clayton (1921)[90]

- Fanny Brice (1923)[105]

- Isabella Patricola ("Miss Patricola") (1923, 1926, 1927, 1938)[106]

- Cecilia Loftus (1923)[107]

- Trixie Friganza (1924)[108]

- Florence Mills (1924)[109]

- Cliff Edwards (1924)[110]

- Doc Rockwell (1925)[111]

- Weber and Fields (1925)[112]

- Hamilton Sisters and Fordyce (the Three X Sisters) and Jerry and Her Baby Grands (1925 or 1926)[113]

- Eva Tanguay (1926)[114]

- Barto and Mann (1927, 1929)[115][116]

- Ethel Waters (1927)[117]

- Julian Eltinge (1927)[118]

- the Duncan Sisters (1927)[119]

- Clark and McCullough (1928)[120]

- Clayton, Jackson & Durante (1928)[121]

- Buck and Bubbles (1928, 1929)[122]

- Harry Langdon (1929)[123]

- Mary Hay and Clifton Webb (1929)[124]

- Phil Baker (1930, 1931, 1932)[125]

- George Jessel (1930)[95]

- Adelaide Hall (1930, 1931, 1933)[126][127][128]

Other performers

Other performers appearing at the Palace included:

- Burns and Allen[129][130]

- Jack Benny[129]

- Sarah Bernhardt[82][129]

- Eddie Cantor[129][131]

- Vernon and Irene Castle[129][132]

- Gus Edwards[133]

- Frank Fay[83]

- Benny Fields[134]

- Bob Hope[129]

- Eddie Leonard[135]

- George Jessel[83][129]

- Helen Kane[131]

- Bert Lahr[136]

- Ethel Merman[137]

- Bill Robinson[138]

- Blossom Seeley[129][134]

- Kate Smith[83][129]

- Sophie Tucker[139]

Decline

The circuit became Keith–Albee–Orpheum in 1925 and it acquired film companies the following year.[64] With the Great Depression came a rise in the popularity of film and radio, and vaudeville saw a steep decline.[140][129] The Paramount Theatre of 1926 and Roxy Theatre of 1927, in particular, were major competitors to the Palace.[15] Many bills were held at the Palace for several consecutive weeks due to their popularity, which turned away subscription holders who wished for more variety; furthermore, many acts demanded increased salaries.[131] After Keith–Albee–Orpheum merged with RCA and the Film Booking Office to form RKO Pictures in 1928, the circuit's vaudeville houses became movie houses.[64] In 1929, the Keith's booking office relocated from the fifth floor of the office wing to the sixth.[70]

To attract vaudeville-goers, the Palace added an electric piano in the lobby and colored lights in the auditorium during the late 1920s.[15] Vaudeville was still popular as late as 1931, when Kate Smith had a ten-week-long run.[141] After considering a three-a-day production,[137][142][e] the Palace moved to four shows a day in May 1932 and lowered its admission prices.[144][145] A fifth show was subsequently added, but this failed to increase the number of attendees.[143]

Post-vaudeville

Movie palace use

The last week of straight vaudeville at the Palace premiered July 9, 1932, featuring Louis Sobol.[141][146] Afterward, the Palace instituted a mixed policy of vaudeville before a feature film,[141][146][147] which continued for several months.[148] The last vaudeville accompaniment took place on November 12, 1932,[149] with Nick Lucas and Hal Le Roy appearing on the closing bill.[150] Thereafter, the Palace was converted to a movie palace, showing films exclusively under RKO Pictures.[151] The film-only policy was not initially successful because many major studios already operated their own theaters in Times Square.[152] Theatrical historian Louis Botto said that "from the 1930s on, it was a constant struggle for survival" for the Palace, which frequently flipped between film-only, vaudeville/film, and live performance formats.[153]

The Palace reverted to a vaudeville-before-film policy on January 7, 1933, two months after it started showing films exclusively.

In preparation for the 1939 New York World's Fair, RKO began to erect a 40-by-25-foot (12.2 by 7.6 m) marquee in front of the office wing in April 1939.[158] The next month, RKO announced the Palace would be renovated.[159] The alterations included renovating the outer lobby with black-and-white granite walls and the inner lobby with zebra wood and black marble walls. Additionally, aluminum and bronze frames were installed in the outer lobby.[89][159][160] The work also included installing doors between the inner and outer lobbies.[161] The renovations were finished in August 1939.[160][161] Further renovations followed in the early 1940s, when some of the boxes were removed since they did not have a good view of the cinema screen.[89]

Attempted revival of vaudeville

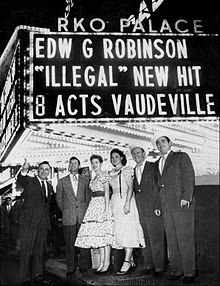

The RKO Palace was closed for a $60,000 renovation in early 1949.[152][162] It received new seats and carpets; upgraded acoustic features and stage; and a new ticket booth in the lobby.[89][163] Beginning in May 1949, under RKO vice president Sol Schwartz, the RKO Palace tried to revive vaudeville with a slate of eight acts before a feature film.[152][164] Within two months of vaudeville being reintroduced, Schwartz said patronage was "very encouraging".[165] The Palace was closed for a two-week renovation in October 1951.[152][166] After the Palace reopened, Judy Garland staged a 19-week comeback at the venue,[86][167] supported by acts such as Max Bygraves.[168] This was the first occurrence of two-a-day vaudeville at the Palace in nearly 18 years.[166] The Palace also attracted acts including Lauritz Melchior,[168][169] José Greco,[168][170] Betty Hutton,[171][172] Danny Kaye,[173][174] Dick Shawn,[175] and Phil Spitalny.[175][176] Garland returned for a successful run in 1956, this time with Alan King.[177]

While the shows were successful, they did not lead to a revival of the vaudeville format.[168] According to theatrical historian Ken Bloom, the Palace "limped along into the fifties with an occasional good week", but the popularity of television had restricted the profitability of the Palace's vaudeville.[152] Performances by Jerry Lewis and Liberace, in 1957, failed to attract enough audience members.[178] As a result, the Palace dropped its vaudeville policy in July 1957.[179] Its film screenings began with James Cagney's Man of a Thousand Faces on August 13, 1957.[178][180] The films included The Diary of Anne Frank, which premiered in 1959.[181][182] The Palace hosted one more vaudeville performance by Harry Belafonte[183] in December 1959.[184][185]

Broadway theater

Nederlander conversion

The RKO Palace was no longer profitable as a cinema by March 1965, and RKO considered selling it to

The Nederlanders spent $500,000 to renovate the venue into a legitimate theater.[89][189] Many of the decorations that were added after the theater's opening were removed, revealing the original design.[89][189][193] Among the decorations uncovered were ironwork, marble balustrades, and the molded ceiling of the lobby.[194] In the basement, workers found a gold vault that was filled with paint cans, as well as crystal chandeliers. The auditorium was outfitted with red decorations and gold-and-cream walls, while the basement was renovated to include a dressing room for the primary performer.[189] Two bars were installed: one in the lobby and one in the basement.[195] The renovations made the Palace the only Broadway theater that was actually on Broadway,[190] and, with 1,732 seats, the largest Broadway house.[193] Ralph Alswang oversaw the restoration of the Palace.[153][189] The Stage magazine printed the Palace Theatre's programs, competing with Playbill magazine, the traditional publisher of stage programs.[196]

On January 29, 1966, the Palace opened as a Broadway venue with the original production of the musical

During the 1970s, the Palace hosted live performances from

1980s renovation to 2010s

Developer Larry Silverstein had planned to build a skyscraper on the Palace Theater's site since the mid-1980s. Such a development was contingent on his ability to acquire a Bowery Savings Bank branch at the corner of 47th Street and Seventh Avenue, surrounded by the original Palace Theatre building.[21] Even after acquiring that site, he had to wait until after the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) reviewed the theater for city-landmark status in 1987. If the landmark status was approved, Silverstein would have to build around the theater.[230][231] This was part of the LPC's wide-ranging effort in 1987 to grant landmark status to Broadway theaters.[47] Ultimately, only the interior was designated as a landmark; a similar status for the exterior was denied.[47][48] In late 1987, the theater closed after the last performance of La Cage aux Folles.[5]

The New York City Board of Estimate ratified the landmark designation in March 1988.[232] The Nederlanders, the Shuberts, and Jujamcyn collectively sued the LPC in June 1988 to overturn the landmark designations of 22 theaters, including the Palace, on the merit that the designations severely limited the extent to which the theaters could be modified.[233] The lawsuit was escalated to the New York Supreme Court and the Supreme Court of the United States, but these designations were ultimately upheld in 1992.[234] Meanwhile, the office wing was demolished (except for the lobby[24]), as were two stories above the auditorium and two ancillary structures.[5][6] Silverstein developed a 43-story Embassy Suites hotel on the site.[21][23][24] The theater received a $1.5 million renovation[31] as part of the $150 million hotel project.[23] The hotel was completed in September 1990.[24]

2010s and 2020s renovation

In 2015, the Nederlander Organization and Maefield Development announced another renovation in conjunction with the TSX Broadway development. The project would include a new lobby and entrance on 47th Street as well as dressing rooms and other patron amenities. The landmark interior would be raised 30 feet (9.1 m) to accommodate ground-floor retail spaces.[38][39][263] The LPC approved the plan in November 2015, even as many preservationists expressed concern over the idea.[42][264][265] The New York City Council approved the plan in June 2018,[266][267] allowing the redevelopment to progress.[268] The musical SpongeBob SquarePants was the last show to play at the theater prior to the renovation, running from December 2017[269][270] to September 2018.[271] Demolition of the existing structure began in late 2019.[7][8]

The reconstruction was originally estimated to keep the Palace closed until 2021.[272] The renovation was delayed during 2019 because the contractors needed to inspect an adjacent building, but the property's owners did not grant permission for the inspection for over a year.[273] The old 1568 Broadway building was being demolished by early 2020.[274] Work was only interrupted for three weeks during the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City, as the TSX Broadway project had hotel rooms and was thus classified as an "essential jobsite".[275] Construction of TSX Broadway's superstructure began the next year.[276][277] The theater also underwent a $50 million renovation, which involved restoring the plasterwork and original chandelier, adding sound insulation, and erecting a new box office and new restrooms.[46]

The auditorium was raised starting in January 2022.[37][278][279] During the lift, the bottom of the auditorium was cushioned by a 5-foot-thick (1.5 m) layer of concrete,[37][279] installed by foundation engineer Urban Foundation Engineering.[36] The lift was conducted using 34 hydraulic posts,[46][279][275] which were sunk 30 feet (9.1 m) into the ground.[33] The posts consisted of telescoping beams,[33] which moved the auditorium by 0.25 inches (6.4 mm) an hour.[279] After the theater had been raised 16 or 17 feet (4.9 or 5.2 m), in March 2022, the lifting process was temporarily paused while the new structural frame was installed.[33][44] The lifting process was completed on April 5, 2022,[33] though the formal celebration was held the next month.[280][281] Afterward, the permanent supports under the auditorium were installed. At the time, TSX Broadway was planned to be completed in 2023,[46] though this was then delayed to the first quarter of 2024.[282] In March 2024, the Nederlander Organization announced that the theater would reopen on May 28, 2024, with a three-week concert residency by Ben Platt.[283][284] This will be followed by the musical Tammy Faye, which is scheduled to open in November 2024.[285]

Alleged haunting

The ghost of acrobat Louis Bossalina allegedly haunts the theater. Observers have said that the ghost is a white-clothed figure swinging in the air before emitting a "blood-curdling scream" and falling.[286][287] Bossalina, who was a member of the acrobatic act the Four Casting Pearls, was injured when he fell 18 feet (5.5 m) during a performance on August 28, 1935, before 800 theatergoers.[286][287] Bossalina's act was not a trapeze but rather fixed towers in which the acrobats were "cast from one to the other".[288] Comedian Pat Henning started his act in front of a curtain that was pulled right after the accident.[288] Bossalina died in 1963.[286][287] According to television channel NY1, sightings of Bossalina only occurred through the 1980s,[286] though another source cited a sighting in the 1990s during a showing of Beauty and the Beast.[287]

Notable productions

Productions are listed by the year of their first performance. This list only includes Broadway shows; it does not include vaudeville shows or films.[52][49]

- 1966: Sweet Charity[289][200]

- 1967: Henry, Sweet Henry[199][205]

- 1968: George M![289][207]

- 1970: Applause[289][216]

- 1973: Cyrano[175][290]

- 1974: Lorelei[289][219]

- 1975: Goodtime Charley[291]

- 1976: Home Sweet Homer[292]

- 1976: Shirley MacLaine Live at the Palace[293]

- 1976: An Evening with Diana Ross[294]

- 1977: Man of La Mancha[221]

- 1979: The Grand Tour[22][295]

- 1979: Beatlemania[296]

- 1979: Oklahoma![223]

- 1981: Woman of the Year[22][226]

- 1983: La Cage aux Folles[22][297]

- 1991: The Will Rogers Follies[22][236]

- 1994: Beauty and the Beast[22][239]

- 1999: Minnelli on Minnelli: Live at the Palace[298]

- 2000: Aida[22][242]

- 2005: All Shook Up[22][299]

- 2006: Lestat[22][300]

- 2007: Legally Blonde[243][244]

- 2008: Liza's at The Palace....[301]

- 2009:

- 2011:

- 2012: Annie[249][250]

- 2014: Holler If Ya Hear Me[255][256]

- 2014: The Temptations and the Four Tops on Broadway[302]

- 2015: An American in Paris[257][258]

- 2016: The Illusionists: Turn of the Century[259][260]

- 2017: Sunset Boulevard[261][262]

- 2017: SpongeBob SquarePants[269][270]

- 2024: Ben Platt[283]

- 2024: Tammy Faye[285]

See also

- List of Broadway theaters

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan from 14th to 59th Streets

References

Notes

- ^ a b c This capacity is approximate and may vary depending on the show.[49] Playbill gives a different figure of 1,610 seats.[52]

- ^ One source cited the hotel as being 44 stories tall.[25]

- ^ Some sources cite the theater as being raised by 29 feet (8.8 m).[38][39]

- ^ According to Slide 2012, p. 385, Keith and Albee only had 51 percent ownership.

- ^ Bloom 2007, pp. 203–204, says the Palace was three-a-day by 1929,[143] but a 1932 New York Daily News article cites the Palace as the "only all-vaudeville two-a-day theatre in the country".[142]

Citations

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 1.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- ^ a b c d e "Palace Theatre in New York, NY". Cinema Treasures. March 24, 1913. Archived from the original on September 12, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

- ISBN 978-1-5381-0786-7. Archivedfrom the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

- ^ from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ ProQuest 962873540.

- ^ a b "Demolition for $2.5B Times Square hotel begins". Crain's New York Business. November 26, 2019. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

- ^ a b Morris, Sebastian (November 27, 2019). "Demolition Kicks Off at 1568 Broadway in Times Square, Future Home of TSX Broadway". New York YIMBY. Archived from the original on March 5, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

- ^ ProQuest 128413440.

- ^ from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

- ^ from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

- ^ ProQuest 555860548.

- ^ a b "Leases". The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 88, no. 2284. December 23, 1911. p. 954. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ ProQuest 128345831.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 14.

- ^ from the original on October 18, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- ^ ProQuest 575069440.

- ^ PBDW Architects 2015, p. 9.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, pp. 13–14.

- ^ a b Harriman 1991, p. 107.

- ^ from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Bloom 2007, p. 206.

- ^ ProQuest 398094707.

- ^ OL 22741487M.

- ^ a b Harriman 1991, p. 109.

- ^ from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on December 19, 2017. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Harriman 1991, p. 108.

- ^ a b PBDW Architects 2015, p. 13.

- ^ from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Times Square Hotel Owner, LLC (2018). 1568 Broadway Text Amendment and Rehabilitation Special Permit; Environmental Assessment Statement (PDF) (Report). New York City Department of City Planning. p. B3 (PDF p. 46).

- ^ from the original on September 23, 2022. Retrieved May 29, 2022.

- ^ Gannon, Devin (January 2, 2020). "Times Square's Palace Theatre overhaul includes outdoor stage and 'ball drop' suites". 6sqft. Archived from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ a b Herzenberg, Michael (March 29, 2019). "Jacked Up: B'Way's Famed Palace Theatre Will Rise Again". Spectrum News NY1 | New York City. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Bousquin, Joe (May 6, 2021). "$2.5B TSX Broadway project rising over Times Square". Construction Dive. Archived from the original on May 7, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Cubarrubia, Eydie (November 3, 2021). "Palace Theatre Begins 30-ft Climb Into TSX Broadway". Engineering News-Record. Archived from the original on January 16, 2023. Retrieved January 31, 2022.

- ^ a b Viagas, Robert (November 25, 2015). "Broadway's Palace Theatre Will Be Lifted by 4 Floors to Make Room for Retail Space". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

- ^ a b c Schulz, Dana (November 20, 2015). "Historic Palace Theater to Get Raised 29 Feet to Accommodate New Retail Space". 6sqft. Archived from the original on March 5, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- ^ PBDW Architects 2015, p. 30.

- ^ a b "Palace Theater". PBDW Architects. October 9, 2018. Archived from the original on May 27, 2020. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- ^ from the original on February 20, 2017. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ^ "Palace Theatre Raising the Roof – And Everything Else – 29 Feet for Commercial Space". amNewYork. December 17, 2015. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- ^ a b Stabile, Tom (March 15, 2022). "TSX Broadway Joins Old to New in Times Square". Engineering News-Record. Archived from the original on January 16, 2023. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ^ PBDW Architects 2015, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d Baird-Remba, Rebecca (May 9, 2022). "How the Palace Theatre Ended Up 30 Feet Above Manhattan". Commercial Observer. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- ^ from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4384-3769-9.

- ^ a b c "Palace Theatre – New York, NY". Internet Broadway Database. January 29, 1966. Archived from the original on March 6, 2020. Retrieved February 18, 2022.

- ^ "Palace Theatre on Broadway in NYC". NYTIX. July 26, 2018. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- ^ "Palace Theatre – Theaters". Broadway.com. Archived from the original on February 27, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- ^ a b "Palace Theatre (1913)". Playbill. Archived from the original on February 18, 2022. Retrieved February 18, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 19.

- ^ a b c d Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, pp. 19–20.

- ^ a b c d Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 20.

- ^ a b c d Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 21.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 22.

- ^ PBDW Architects 2015, p. 34.

- ^ a b PBDW Architects 2015, p. 35.

- ^ "Palace Theatre". New York City Chapter of the American Guild of Organists. March 24, 1913. Archived from the original on June 8, 2009. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 10.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8061-3315-7. Archivedfrom the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

- OCLC 61115601.

- ^ a b c d e Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 11.

- ProQuest 97301107.

- ^ a b c d e Bloom 2007, p. 203.

- ^ Bloom 2007, p. 203; Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 65.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-19-972305-8. Archivedfrom the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ^ a b c Slide 2012, p. 386.

- ^ ProQuest 1475834322.

- ^ a b "Palace Theatre Bid for: Werba & Luescher Obtain Option From Martin Beck in New Deal". New-York Tribune. May 31, 1912. p. 7. Archived from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ProQuest 1031442853.

- ProQuest 1529180082.

- ProQuest 1529147725.

- from the original on August 8, 2020. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- ^ ProQuest 575065576.

- ^ a b c d Slide 2012, p. 385.

- ^ a b Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 65.

- ^ Bloom 2007, p. 203; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 16.

- ^ ProQuest 1529327941.

- ^ Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 65; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 16.

- ^ a b Bloom 2007, p. 203; Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 65; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 16; Slide 2012, p. 385.

- ^ from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ^ a b c Slide 2012, pp. 385–386.

- ^ ProQuest 1528979624.

- ^ from the original on April 21, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ Trav S.D. 2006, p. 160.

- from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 15.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-415-93853-2. Archivedfrom the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ISBN 0-674-62734-2. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

bayes.

- ISBN 978-0-415-91936-4. Archivedfrom the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-8061-3704-9. Archivedfrom the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-55553-317-5. Archivedfrom the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-89950-968-6. Archivedfrom the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ^ Slide 2012, p. 163.

- ^ Slide 2012, p. 81.

- ^ Slide 2012, p. 170.

- ^ Trav S.D. 2006, p. 169.

- ISBN 978-0-465-01811-6. Archivedfrom the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-8131-4572-3. Archivedfrom the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-7864-6916-1. Archivedfrom the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-313-28027-6. Archivedfrom the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

- ^ "Palace Theatre newspaper advertisement — January 24, 1921". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-253-20762-3. Archivedfrom the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ^ Slide 2012, p. 392.

- ^ Slide 2012, p. 323.

- ^ Slide 2012, p. 199.

- ISBN 978-1-57958-389-7. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ISBN 978-1-138-87023-9. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ^ Slide 2012, p. 420.

- ISBN 978-0-415-93853-2. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ^ Santos, Glenn A. (November 26, 2014). "Hamilton Sisters Jerry and Her Baby Grands".

- OCLC 162210.

- ^ "Vaudeville Charts on Past Performance". Zit's Theatrical Newspaper. July 30, 1927.

- ^ "Vaudeville Charts on Past Performance". Zit's Theatrical Newspaper. March 16, 1929.

- ISBN 978-0-06-124173-4. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

Heat Wave: The Life and Career of Ethel Waters.

- ISBN 978-0-87000-492-6. Archivedfrom the original on February 22, 2024. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-8108-3534-4. Archivedfrom the original on February 22, 2024. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- from the original on October 18, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- ^ Bakish 1994, p. 39.

- ^ Folkart, Burt A. (May 20, 1986). "John Bubbles, Tap-Dance Great, Gershwin Performer, Dies at 84". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-7864-3691-0. Archivedfrom the original on February 22, 2024. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-472-06858-6. Archivedfrom the original on February 22, 2024. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ^ Slide 2012, p. 21.

- ^ Gardner, Chappie (February 22, 1930). "White Press Acclaims Adelaide Hall As Packed House Gives Her Great Ovation". Pittsburgh Courier. p. 16. Retrieved June 12, 2013.

- ISBN 978-0-8264-5893-3. Archived from the original on February 22, 2024. Retrieved October 3, 2020.; June 1933

August 1930: Adelaide headlines with Bill 'Bojangles' Robinson; February, April, July & November 1931: Adelaide appears four times during her 1931/32 world tour with Noble Sissle

- ISBN 978-0-8108-8350-5. Archivedfrom the original on February 22, 2024. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ^ from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ProQuest 1114153268.

- ^ from the original on October 29, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ProQuest 575170857.

- ProQuest 576406924.

- ^ from the original on October 29, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ProQuest 1112650462.

- ProQuest 1114174753.

- ^ from the original on October 29, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- from the original on October 29, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ^ Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 67; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 11.

- ^ a b c Bloom 2007, p. 204; Slide 2012, p. 386.

- ^ from the original on October 28, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Bloom 2007, pp. 203–204.

- ProQuest 1529005624.

- ProQuest 1114515620.

- ^ ProQuest 1114523398.

- from the original on October 29, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ^ Bloom 2007, p. 203; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 17.; Slide 2012, p. 386.

- ^ a b Bloom 2007, p. 204; Slide 2012, pp. 386–387.

- ISBN 978-0-517-54346-7. Archivedfrom the original on February 22, 2024. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- from the original on October 18, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bloom 2007, p. 204.

- ^ a b c Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 67.

- ProQuest 1221640244.

- ProQuest 100651471.

- ProQuest 558730672.

- from the original on October 18, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- ProQuest 1505733492.

- ^ from the original on March 10, 2018. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- ^ ProQuest 1627488067.

- ^ ProQuest 1319968617.

- ProQuest 1565320485.

- from the original on March 29, 2018. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- from the original on October 29, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ^ ProQuest 1313652447.

- ^ Bloom 2007, pp. 204–205; Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 67.

- ^ a b c d Slide 2012, p. 387.

- from the original on October 18, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- from the original on October 18, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- ^ Bloom 2007, p. 204; Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 67; Slide 2012, p. 387.

- from the original on October 18, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- ^ Bloom 2007, pp. 204–205; Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 67; Slide 2012, p. 387.

- from the original on October 18, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Bloom 2007, p. 205.

- from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- ^ a b Bloom 2007, pp. 204–205.

- ^ a b Bloom 2007, p. 205; Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 67; Slide 2012, p. 387.

- from the original on October 18, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- from the original on November 6, 2020. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- from the original on June 23, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ^ Bloom 2007, p. 205; Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 67.

- ^ Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 67; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 18.

- from the original on October 18, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- from the original on October 29, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ^ from the original on February 24, 2020. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

- ^ from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ from the original on October 29, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ^ ProQuest 1014835726.

- ^ ProQuest 963003262.

- ^ ProQuest 1032426965.

- ^ ProQuest 1014840320.

- ^ Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 67; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 15.

- from the original on October 29, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- from the original on July 12, 2022. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- ^ Bloom 2007, p. 205; Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 67; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 18.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 69.

- ^ a b "Sweet Charity Broadway @ Palace Theatre". Playbill. April 27, 1986. Archived from the original on September 22, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

"Sweet Charity – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. January 29, 1966. Archived from the original on September 25, 2017. Retrieved November 12, 2021. - from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ^ Botto & Mitchell 2002, pp. 67–69.

- from the original on November 21, 2021. Retrieved November 21, 2021.

- ^ a b "Henry, Sweet Henry Broadway @ Palace Theatre". Playbill. December 31, 1967. Archived from the original on July 12, 2020. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

"Henry, Sweet Henry – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. October 23, 1967. Archived from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021. - ^ Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 69; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 29.

- ^ a b "George M! Broadway @ Palace Theatre". Playbill. April 26, 1969. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

"George M! – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. April 10, 1968. Archived from the original on November 11, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021. - from the original on February 12, 2018. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on June 24, 2020. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- from the original on January 28, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ^ "The 25th Annual Tony Awards – 1971 Broadway @ Palace Theatre". Playbill. March 28, 1971. Archived from the original on March 16, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ^ a b Bloom 2007, p. 205; Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 69; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 18.

- from the original on July 12, 2022. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- from the original on April 22, 2022. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- ^ a b "Applause Broadway @ Palace Theatre". Playbill. July 27, 1972. Archived from the original on June 13, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

"Applause – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. March 30, 1970. Archived from the original on October 3, 2016. Retrieved November 12, 2021. - from the original on July 12, 2022. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- from the original on July 12, 2022. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- ^ a b "Lorelei Broadway @ Palace Theatre". Playbill. November 3, 1974. Archived from the original on March 16, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

"Lorelei – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. January 27, 1974. Archived from the original on December 3, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021. - ^ a b Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 69; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 18.

- ^ a b "Man of La Mancha Broadway @ Palace Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on March 17, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

"Man of La Mancha – Broadway Musical – 1977 Revival". Internet Broadway Database. September 15, 1977. Archived from the original on November 13, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021. - from the original on August 26, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ^ a b "Oklahoma! Broadway @ Palace Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on February 9, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

"Oklahoma! – Broadway Musical – 1979 Revival". Internet Broadway Database. December 13, 1979. Archived from the original on November 23, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021. - from the original on July 12, 2022. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- from the original on July 12, 2022. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- ^ a b "Woman of the Year Broadway @ Palace Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 1, 2020. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

"Woman of the Year – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. March 29, 1981. Archived from the original on March 31, 2015. Retrieved November 12, 2021. - ^ a b Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 70.

- from the original on July 12, 2022. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- ^ "La Cage aux Folles Broadway @ Palace Theatre". Playbill. November 15, 1987. Archived from the original on March 6, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved November 20, 2021.

- from the original on October 29, 2021. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- ^ a b Bloom 2007, p. 206; Botto & Mitchell 2002, p. 70.

- ^ a b c "The Will Rogers Follies Broadway @ Palace Theatre". Playbill. September 5, 1993. Archived from the original on February 28, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

"The Will Rogers Follies – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. April 1, 1991. Archived from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021. - from the original on September 29, 2016. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- from the original on October 17, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

- ^ a b "Beauty and the Beast Broadway @ Palace Theatre". Playbill. March 9, 1994. Archived from the original on October 5, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

"Beauty and the Beast – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. April 18, 1994. Archived from the original on December 6, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021. - from the original on September 11, 2020. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Aida Broadway @ Palace Theatre". Playbill. February 25, 2000. Archived from the original on July 5, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

"Aida – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. March 23, 2000. Archived from the original on November 19, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021. - ^ a b "Legally Blonde Broadway @ Palace Theatre". Playbill. April 3, 2007. Archived from the original on September 22, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

"Legally Blonde – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. April 29, 2007. Archived from the original on July 4, 2008. Retrieved November 12, 2021. - ^ from the original on January 5, 2018. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ^ a b "West Side Story Broadway @ Palace Theatre". Playbill. February 23, 2009. Archived from the original on September 23, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

"West Side Story – Broadway Musical – 2009 Revival". Internet Broadway Database. March 19, 2009. Archived from the original on November 15, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021. - ^ from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ^ a b "Priscilla Queen of the Desert Broadway @ Palace Theatre". Playbill. February 28, 2011. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

"Priscilla Queen of the Desert – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. March 20, 2011. Archived from the original on December 9, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021. - ^ a b Itzkoff, Dave (May 16, 2012). "Broadway Musical 'Priscilla Queen of the Desert' to Close". ArtsBeat. Archived from the original on June 27, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ^ a b "Annie Broadway @ Palace Theatre". Playbill. October 3, 2012. Archived from the original on November 12, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021.

"Annie – Broadway Musical – 2012 Revival". Internet Broadway Database. November 8, 2012. Archived from the original on December 7, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021. - ^ a b Healy, Patrick (September 5, 2013). "Broadway 'Annie' to Close in January". ArtsBeat. Archived from the original on October 2, 2019. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ^ "9 Broadway theaters to gain disabled accessibility". Times Union. Albany. January 29, 2014. Archived from the original on December 30, 2021. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- ^ "9 Broadway theaters to gain disabled accessibility". Yahoo! Finance. February 11, 2015. Archived from the original on December 30, 2021. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2021.

- ^ Gioia, Michael (April 23, 2014). "Broadway's Palace Theatre Given $200,000 Makeover for Holler If Ya Hear Me". Playbill. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ^ a b "Holler If Ya Hear Me Broadway @ Palace Theatre". Playbill. May 29, 2014. Archived from the original on March 3, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

"Holler If Ya Hear Me – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. June 19, 2014. Archived from the original on October 28, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021. - ^ a b Healy, Patrick (July 14, 2014). "'Holler if Ya Hear Me' to Close on Sunday". ArtsBeat. Archived from the original on December 19, 2021. Retrieved February 23, 2022.

- ^ a b "An American in Paris Broadway @ Palace Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on September 29, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

"An American in Paris – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021. - ^ from the original on February 23, 2022. Retrieved February 23, 2022.

- ^ a b "The Illusionists – Turn of the Century Broadway @ Palace Theatre". Playbill. November 25, 2016. Archived from the original on October 15, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

"The Illusionists – Turn of the Century – Broadway Special – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on December 1, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021. - ^ from the original on December 28, 2023. Retrieved December 28, 2023.

- ^ a b "Sunset Boulevard Broadway @ Palace Theatre". Playbill. February 2, 2017. Archived from the original on March 3, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

"Sunset Boulevard – Broadway Musical – 2017 Revival". Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on October 8, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021. - ^ from the original on March 24, 2022. Retrieved February 23, 2022.

- ^ Bindelglass, Evan (November 25, 2015). "Palace Theater To Be Lifted 29 Feet For Expanded Facilities And Retail". New York YIMBY. Archived from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ Viagas, Robert (November 25, 2015). "Broadway's Palace Theatre Will Be Lifted by Four Floors to Make Room for Retail Space". Playbill. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ^ Bindelglass, Evan (November 25, 2015). "Palace Theater To Be Lifted 29 Feet For Expanded Facilities And Retail". New York Yimby. Archived from the original on April 26, 2018. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- ^ "City Council approves plans for TSX Broadway redevelopment". The Real Deal New York. June 28, 2018. Archived from the original on September 23, 2018. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ^ Warerkar, Tanay (June 29, 2018). "Times Square's Palace Theatre revamp gets City Council approval". Curbed NY. Archived from the original on September 24, 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ "Huge retail and hotel project moves forward in Times Square". Crain's New York Business. September 21, 2018. Archived from the original on January 3, 2019. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- ^ a b "SpongeBob SquarePants, The Broadway Musical Broadway @ Palace Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on February 14, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

"SpongeBob SquarePants – Broadway Musical – Original". IBDB. Archived from the original on November 2, 2019. Retrieved November 12, 2021. - ^ from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ "'SpongeBob Squarepants' musical taking its final bow on Broadway". Spectrum News. New York City. September 16, 2018. Archived from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ Warerkar, Tanay (June 29, 2018). "Times Square's Palace Theatre revamp gets City Council approval". Curbed. Archived from the original on September 23, 2018. Retrieved October 14, 2018.

- ^ Hershberg, Marc (January 13, 2019). "Palace Theatre Project Hits a Snag". Forbes. Archived from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ Young, Michael (April 30, 2020). "Demolition Steadily Progressing at 1568 Broadway, Future Home of TSX Broadway, in Times Square". New York YIMBY. Archived from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ a b Thibault, Matthew (February 18, 2022). "Stars align to hoist historic Times Square theater for mixed-use project". Construction Dive. Archived from the original on January 16, 2023. Retrieved March 3, 2022.

- ^ Baird-Remba, Rebecca (May 6, 2021). "New Times Square Megatower, TSX Broadway, Begins to Take Shape". Commercial Observer. Archived from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ "TSX Broadway's New Superstructure Begins Assembly at 1568 Broadway in Times Square, Manhattan". New York YIMBY. April 17, 2021. Archived from the original on October 16, 2021. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ^ Holmes, Helen (January 8, 2022). "Broadway's Palace Theatre Has Begun Its 8 Week, 30 Foot Ascent". Observer. Archived from the original on January 16, 2023. Retrieved January 8, 2022.

- ^ a b c d "Iconic Palace Theatre being lifted 30 feet above Times Square". ABC7 New York. January 7, 2022. Archived from the original on January 16, 2023. Retrieved January 8, 2022.

- ^ "Palace Theatre Completes 30-Foot Lift Within TSX Broadway, at 1568 Broadway in Times Square, Manhattan". New York YIMBY. May 4, 2022. Archived from the original on February 22, 2024. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- ^ Carlin, Dave (May 5, 2022). "Effort to lift Times Square's Palace Theatre 30 feet off the ground finally accomplished". CBS News. Archived from the original on February 22, 2024. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- ^ Young, Michael (June 27, 2023). "TSX Broadway's Tempo By Hilton Prepares For Late-Summer Opening At 1568 Broadway In Times Square, Manhattan". New York Yimby. Archived from the original on September 25, 2023. Retrieved September 26, 2023.

YIMBY was informed that the Tempo by Hilton Times Square is targeting an opening date for later this summer, while the entire TSX Broadway property will open in the first quarter of 2024.

- ^ a b Higgins, Molly (March 18, 2024). "Ben Platt Will Play Concert Residency at Broadway's Palace Theatre". Playbill. Retrieved March 18, 2024.

- ^ Evans, Greg (March 18, 2024). "Ben Platt Sets 18-Performance Residency At Broadway's Newly Refurbished Palace Theatre". Deadline. Retrieved March 18, 2024.

- ^ a b Higgins, Molly (March 22, 2024). "Katie Brayben and Andrew Rannells to Star in Tammy Faye on Broadway". Playbill. Retrieved March 18, 2024.

Quinn, Dave (March 22, 2024). "'Tammy Faye' Heads to Broadway! Elton John and Jake Shears' Divine Musical to Debut This Fall". People. Retrieved March 22, 2024. - ^ a b c d DiLella, Frank (October 27, 2017). "Touring Broadway's haunted past". Spectrum News. New York City. Archived from the original on October 18, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7385-9946-5. Archivedfrom the original on October 18, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- ^ from the original on September 12, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Bloom 2007, p. 205; Landmarks Preservation Commission 1987, p. 18.

- ^ "Cyrano Broadway @ Palace Theatre". Playbill. June 23, 1973. Archived from the original on September 21, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

"Cyrano – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. May 13, 1973. Archived from the original on October 20, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021. - ^ "Goodtime Charley Broadway @ Palace Theatre". Playbill. May 31, 1975. Archived from the original on April 26, 2020. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

"Goodtime Charley – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. March 3, 1975. Archived from the original on February 18, 2022. Retrieved November 12, 2021. - ^ "Home Sweet Homer Broadway @ Palace Theatre". Playbill. January 4, 1976. Archived from the original on February 21, 2020. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

"Home Sweet Homer – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. January 4, 1976. Archived from the original on November 25, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021. - ^ "Shirley MacLaine Broadway @ Palace Theatre". Playbill. July 9, 1976. Archived from the original on December 7, 2017. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

"Shirley MacLaine Broadway @ Palace Theatre". Playbill. April 19, 1976. Archived from the original on September 29, 2020. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

"Shirley MacLaine – Broadway Special – Original". Internet Broadway Database. April 19, 1976. Archived from the original on December 7, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021. - ^ "An Evening with Diana Ross Broadway @ Palace Theatre". Playbill. July 3, 1976. Archived from the original on May 28, 2019. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

"An Evening With Diana Ross – Broadway Special – Original". Internet Broadway Database. June 14, 1976. Archived from the original on October 26, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021. - ^ "The Grand Tour Broadway @ Palace Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on March 4, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

"The Grand Tour – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. January 11, 1979. Archived from the original on December 14, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021. - ^ "Beatlemania Broadway @ Winter Garden Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on December 15, 2020. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

"Beatlemania – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. May 31, 1977. Archived from the original on November 25, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021. - ^ "La Cage aux Folles Broadway @ Palace Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on March 6, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

"La Cage aux Folles – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. August 21, 1983. Archived from the original on December 7, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021. - ^ "Minnelli on Minnelli Broadway @ Palace Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on May 20, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

"Minnelli on Minnelli – Broadway Special – Original". Internet Broadway Database. December 8, 1999. Archived from the original on November 24, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021. - ^ "All Shook Up Broadway @ Palace Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

"All Shook Up – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. March 24, 2005. Archived from the original on November 11, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021. - ^ "Lestat Broadway @ Palace Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on July 13, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

"Lestat – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. April 25, 2006. Archived from the original on November 8, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021. - ^ "Liza's at the Palace.... Broadway @ Palace Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on July 17, 2020. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

"Liza's at the Palace.... – Broadway Special – Original". Internet Broadway Database. December 3, 2008. Archived from the original on November 12, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021. - ^ "The Temptations & The Four Tops On Broadway Broadway @ Palace Theatre". Playbill. Archived from the original on October 15, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2021.

"An American in Paris – Broadway Musical – Original". Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on October 19, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2021.

Sources

- Bloom, Ken (2007). The Routledge Guide to Broadway (1st ed.). New York: Routledge. pp. 203–206. ISBN 978-0-415-97380-9.

- Botto, Louis; Mitchell, Brian Stokes (2002). At This Theatre: 100 Years of Broadway Shows, Stories and Stars. New York; Milwaukee, WI: Applause Theatre & Cinema Books/Playbill. pp. 65–72. ISBN 978-1-55783-566-6.

- Harriman, Marc S. (November 1991). "Spanning History" (PDF). Architecture. pp. 107–109.

- "Palace Theater" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. July 14, 1987.

- PBDW Architects (November 24, 2015). "1564 Broadway" (PDF). Government of New York City. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 11, 2016.

- Slide, Anthony (March 12, 2012). Encyclopedia of Vaudeville. University of Mississippi Press. pp. 385–387. ISBN 978-1-61703-249-3.

- Trav S.D. (October 31, 2006). No Applause, Just Throw Money. Faber & Faber. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-86547-958-6.