Paleolithic religion

| The Paleolithic |

|---|

| ↑ Pliocene (before Homo) |

| ↓ Mesolithic |

Paleolithic religions are a set of

Religious behavior is one of the hallmarks of

Lower Paleolithic

Religion prior to the Upper Paleolithic is speculative,[3] and the Lower Paleolithic in particular has no clear evidence of religious practice.[4] Not even the loosest evidence for ritual exists prior to 500,000 years before the present, though archaeologist Gregory J. Wightman notes the limits of the archaeological record means their practice cannot be thoroughly ruled out.[5] The early hominins of the Lower Paleolithic—an era well before the emergence of H. s. sapiens—slowly gained, as they began to collaborate and work in groups, the ability to control and mediate their emotional responses. Their rudimentary sense of collaborative identity laid the groundwork for the later social aspects of religion.[6]

Australopithecus, the first hominins,

A number of skulls found in archaeological excavations of Lower Paleolithic sites across diverse regions have had significant proportions of the brain cases broken away. Writers such as Hayden speculate that this marks cannibalistic tendencies of religious significance; Hayden, deeming cannibalism "the most parsimonious explanation", compares the behavior to hunter-gatherer tribes described in written records to whom brain-eating bore spiritual significance. By extension, he reads the skull's damage as evidence of Lower Paleolithic ritual practice.[12] For the opposite position, Wunn finds the cannibalism hypothesis bereft of factual backing; she interprets the patterns of skull damage as a matter of what skeletal parts are more or less preserved over the course of thousands or millions of years. Even within the cannibalism framework, she argues that the practice would be more comparable to brain-eating in chimpanzees than in hunter-gatherers.[3] In the 2010s, the study of Paleolithic cannibalism grew more complex due to new methods of archaeological interpretation, which led to the conclusion much Paleolithic cannibalism was for nutritional rather than ritual reasons.[13]

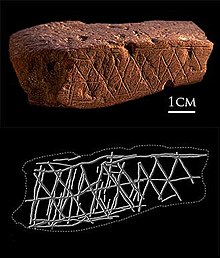

In the Upper Paleolithic, religion is associated with symbolism and sculpture. One Upper Paleolithic remnant that draws cultural attention are the

The tail end of the Lower Paleolithic saw a cognitive and cultural shift. The emergence of revolutionary technologies such as fire, coupled with the course of human evolution extending development to include a true childhood and improved bonding between mother and infant, perhaps broke new ground in cultural terms. It is in the last few hundred thousand years of the period that the archaeological record begins to demonstrate hominins as creatures that influence their environment as much as they are influenced by it. Later Lower Paleolithic hominins built wind shelters to protect themselves from the elements; they collected unusual natural objects; they began the use of pigments such as

Middle Paleolithic

Pigment use

According to

Burials

Graves are the clearest signs of spiritual behavior, as it shows delineation between the world of the living and the world of the dead. Most often, archaeologists will seek to find some form of grave goods, pigment use, or other forms of symbolic behavior to differentiate from burials motivated by other reasons, such as hygiene.[23] Examples of such burials are La Chapelle-aux-Saints 1,[24] Le Regourdou,[25] Shanidar 4,[26] and Teshik-Tash 1,[27] among others.

Ritual cannibalism

Eating the flesh of deceased in order to inherit their qualities or honor them is a practice that has been noted in numerous modern societies, such as the Wariʼ people,[28] and evidence of it may be found in middle Paleolithic as well.

Ritual cannibalism has been suggested for the Krapina Neanderthals, based on three factors: mixing of animals and human skeletal remains, breaking of long bones (in order to access the

Ritual cannibalism has been noted among the early modern humans of the Klasies River Caves, who consumed other anatomically modern humans. Evidence of it has been found at the Les Rois site as well, where early modern humans consumed the flesh of neanderthals.[34]

Skull cult

The idea of a skull cult among the prehistoric people was popular throughout the 20th century, however, subsequent research and re-analysis disproved most of such theories.[35]

The frontal bone of the Krapina 3 cranium has 35 incisions, which cannot be explained through cannibalism, but may be the result of natural processes.

Bear cult

Numerous cave bear skulls were found alongside evidence of human habitation in Middle Paleolithic caves, which lead scientists to assume the existence of a bear cult. The bones were most often of cave bears and more rarely of brown bears.[38] The skulls were placed in a cave niche or other prominent places, presumably for worship. Aside from human activity, the position can also be explained through animal activity or natural processes.[39]

Upper Paleolithic

Upper Paleolithic began about 40 000 BP in Europe, and slightly earlier in Africa and the Levant. Use of pigment and the practice of burial extends into this period, with the addition of

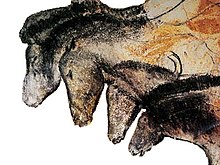

Cave art

According to Richard Klein, the art and burial of the upper paleolithic is the first clear and undeniable proof of an ideological system. The art can be divided into two types: the cave art such as paintings, engravings and reliefs on stone walls, and portable art.[35]

Although first evidence of it was discovered in Europe, the earliest cave art was created in

The idea of

Andre Leroi-Gourhan saw these depictions as a reflection of the natural and supernatural ordering of the world through sexual symbolism. Certain animals (i.e. the bison) were connected to female values and other to male values (i.e. the horse). These interpretations are based on subjective interpretations of modern humans, which don't necessarily reflect the worldviews of the prehistoric peoples.[47]

Shamanism is another popular explanation. The caves would as such represent entrances to the spiritual realm in which one can communicate with spiritual beings. Many of the animals depicted in cave art aren't depicted as hunted, as part of hunting magic. Their depictions would serve to give the shaman their strength and traits to help him during his hallucination, when he would communicate with the supernatural powers. The half-animal, half-man depictions, as for example the Trois-Frères sorcerer, would represent the Lord of Animals.[46] Depictions of women in cave art suggests their participation in these rituals,[48] perhaps through dance accompanied by music.[49]

Portable art

Kozlowski saw animal carvings as connected to hunting magic, aimed at increasing success.

They could have represented fertility goddesses, connected to giving and protecting life, as well as with death and rebirth.[50] Other explanations see these figurines as pornography,[51] auto-portraits[52] or depictions of important women in the tribe. They may have symbolized the hope for prosperous and well-nourished communities.[53]

The

Burials and pigment use

Based on the grave goods found beside the deceased, upper paleolithic burials are undoubtedly evidence of spirituality and religiousness. Pigments of various kinds are found in great amounts in various sites across Europe. The graves best illustrating this are described below:

- stone tools. The man in the middle was lying on a "pillow" of bison bones.[55]

- gracile man with abnormalities.[56]

- Brno II – a rich male burial. An ivory sculpture was found, as well as over 600 ornaments made of tertiary shell, stone and ivory. Two large pierced silicon discs suggest the man buried here was a shaman.[55]

- Sungir – five burials, with two child burials, a boy and a girl. The boy was buried with 4903 ornaments, which were likely attached to his clothes, 250 fox canines, a male femur covered in red ochre, and two small animal statues. The girl was buried with 5274 ornaments. It would have taken over 7000 working hours to produce all these grave goods. A male burial with nearly the same amount of grave goods was found as well, with 2000 working hours being required for the production of his grave goods.[57]

See also

- Anthropology of religion

- Behavioral modernity

- Evolutionary psychology of religion

- Grave field

- Mother Goddess

- Prehistoric religion

Notes

- ^ Predating even Australopithecus was Ardipithecus, which is conceptualized as a hominin by some authors, but whose place in the lineage is a matter of dispute.[7][8]

- ^ The precise timeframe of the Venus of Berekhat Ram is unclear. It was between 230,000 and 780,000 years ago,[15] as determined by the age of the layers of volcanic ash it was found embedded in.[16]

References

- cave artborn 30,000 years before our era ... would appear to have developed simultaneously with the first explicit manifestations of concern with the supernatural." (p. 6)

- S2CID 1904963. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ .

- ISBN 9781588341686.

- ISBN 9781442242890.

- ISBN 9781442242890.

- PMID 20508113.

- .

- hdl:10150/628192.

- ISBN 9780199232444.

- ISBN 9780761858454.

- ^ ISBN 9781588341686.

- PMID 28383521.

- ^ Liew, Jessica (10 July 2017). "Venus Figurine". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ISBN 9780199232444.

- ^ Patowary, Kaushik (13 October 2016). "Venus of Berekhat Ram: The World's Oldest Piece of Art That Predates Humans". Amusing Planet. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- ISBN 9780199232444.

- PMID 19900185.

- ^ ISBN 9781442242890.

- ISBN 978-953-0-61495-6.

- S2CID 4338669. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- S2CID 31169551. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ Milićević Bradač, Marina (2002). "The living, the dead, and the graves". Histria Antiqua. 8: 53–62.

- ISBN 978-0500278079.

- ]

- ^ Arlette Leroi-Gourhan, Shanidar et ses fleurs, Paléorient, vol. 24, pp. 79–88, 1998

- ]

- ^ Robben, A.C.G.M. "Death and Anthropology: An Introduction". In Robben, A.C.G.M. (ed.). Death, Mourning and Burial: A Cross-cultural Reader. Hoboken, New Jersey: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. pp. 1–16.

- ^ Karavanić, Ivor (1993). "Kanibalizam ili mogućnost religijske svijesti u krapinskih neandertalaca". Obnovljeni Život: časopis za filozofiju i religijske znanosti. 48 (1): 100–102. Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ^ Karavanić, Ivor; Patou-Mathis, Marylène (2009). "Middle/Upper Paleolithic interface in Vindija Cave (Croatia): New Results and interpretations". In Camps, M.; Chauhan, P.R. (eds.). Sourcebook of Paleolithic Transitions: Methods, theories and interpretations. New York: Springer.

- PMID 10506562. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ Garralda, Maria Dolores; Giacobini, Giacomo (January 2005). "Cutmarks on the Combe-Grenal and Marillac Neandertals. A SEM analysis". L'Anthropologie. 43. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ de Lumley, H.; de Lumley, M.A.; Brandi, R.; Guerrier, E.; Pillard, F.; Pillard, B. (1972). "Haltes et campements de chasseurs néandertaliens dans la grotte l'Hortus (Valflaunes, Herault)". In de Lumley, H. (ed.). Etudes Quaternaires. Marseille: Laboratoire de Paléontologie Humaine et de Préhistoire. pp. 527–623.

- ^ McKie, Robin (16 May 2009). "How Neanderthals met a grisly fate: devoured by humans". theguardian.com. Retrieved 23 January 2021.

- ^ ISBN 978-0226439655.

- ^ Frayer, David W.; Orschiedt, Jörg; Cook, Jill; Russell, Mary Doria; Radovčić, Jakov (2006). "Krapina 3: Cut Marks and Ritual Behavior?" (PDF). Periodicum Biologorum. 108. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ Malez, Mirko (1985). "Spilja Vindija kao kultno mjesto neandertalaca". Godišnjak Gradskog muzeja Varaždin. 7 (7). Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ISBN 9780705401227.

- ^ Binford, Lewis (1981). Bones: Ancient Men and Modern Myths. Orlando: Academic Press Inc.

- ISBN 978-953-0-61495-6.

- S2CID 86322294. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- PMID 33523879.

- OCLC 6890108.

- S2CID 147269806. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ISBN 978-953-0-61495-6.

- ^ a b Lewis-Williams, David; Clottes, Jean (1998). The Shamans of Prehistory: Trance and magic in painted caves. New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

- . Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ^ a b Kozlowski, Janusz (2004). "Religiozni osjećaj tijekom prapovijesti: gornji paleolitik". In Vandermeersch, Bernard; Kozlowski, Janusz; Gumbutas, Marija; Facchini, Fiorenzo (eds.). Religioznost u prapovijesti. Zagreb: Kršćanska sadašnjost.

- . Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ^ Burkert, Walter (1979). Structure and History in Greek Mythology and Ritual. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 88–89.

- JSTOR 3248385. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- S2CID 144914396. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- . Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ^ , Martin Bailey Ice Age Lion Man is the world’s earliest figurative sculpture The Art Newspaper, 31 January 2013, accessed 1 February 2013.[1] Archived 2015-02-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Aldhouse-Green, Miranda; Aldhouse-Green, Stephen (13 June 2005). The Quest for the Shaman: Shape-Shifters, Sorcerers and Spirit-healers of Ancient Europe. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd.

- ^ Svoboda, Jiří (2006). "The Burials: Ritual and Taphonomy". In Svoboda, Jiří; Trinkaus, Erik (eds.). Early Modern Human Evolution in Central Europe: The people of Dolni Vestonice and Pavlov. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ^ White, Randall (2006). "Technological and social dimensions of "Aurignacian-age" body ornaments across Europe". In Knecht, Heidi; Piketay, Anne; White, Randall (eds.). Before Lascaux: The Complex Record of the Early Upper Paleolithic. Boca Raton: CRC Pres. pp. 277–299.