Palaeoloxodon falconeri

| Palaeoloxodon falconeri | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted skeleton, Nebraska State Museum of Natural History

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Proboscidea |

| Family: | Elephantidae |

| Genus: | †Palaeoloxodon |

| Species: | †P. falconeri

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Palaeoloxodon falconeri (Busk, 1867)

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Palaeoloxodon falconeri is an extinct species of

Chronology

Palaeoloxodon falconeri derives from the 4 metre tall

Taxonomy

In 1867, George Busk had proposed the species Elephas falconeri for many of the smallest molars selected from the material originally ascribed by Hugh Falconer to Palaeoloxodon melitensis for the Maltese dwarf elephant, a possible subspecies of P. falconeri.[4][5] The species Elephas/Palaeoloxodon melitensis, formerly considered a distinct species, is now considered a synonym of P. falconeri.[6]

Description

This island-bound elephant is considered to be an example of insular dwarfism, with adult individuals around the size of modern elephant calves. In a 2015 study of specimens from Spinagallo Cave, a composite adult male specimen MPUR/V n1 was estimated to measure 96.5 cm (3 ft 2.0 in) in shoulder height about 305 kg (672 lb) in weight, a composite adult female specimen MPUR/V n2 80 cm (2 ft 7.5 in) in shoulder height and about 168 kg (370 lb) in weight, and a composite newborn male specimen MPUR/V n3 33 cm (1 ft 1.0 in) in shoulder height and about 6.7 kg (15 lb) in weight.[7] A later 2019 volumetric study revised the weight estimates for the adult male and adult female to about 250 kg (551 lb) and 150.5 kg (332 lb) respectively. The newborn male of the species was estimated in the same study to weigh 7.8 kg (17 lb).[6]

The morphology of the skull demonstrates neotenic traits similar to those present in juvenile elephants, including the loss of the fronto-parietal crest present in other Palaeoloxodon species. The brain was around the size of a human's, and proportionally much larger relative to skull and body size than P. antiquus. In comparison to adult P. antiquus individuals, the neck was elongated, the torso was proportionally wider and longer, and the forelimbs were shorter while the hindlimbs were longer, resulting in a concave back. The limbs were proportionally more slender than P. antiquus, presumably because they needed to bear less weight.[7] The feet were more digitigrade than modern elephants due to being proportionally narrower and higher.[6] The morphology of the limbs and feet suggest that P. falconeri may have been more nimble than living elephants, and better able to move on steep and uneven terrain. Female members of the species were tuskless. Due to the much smaller body size resulting in increased heat loss, it is possible that the species was covered by a more dense coat of hair than present in living elephants in order to maintain a stable body temperature, though if it was present it was still likely sparse, due to elephants lacking sweat glands. The ears were also likely proportionally much smaller than living elephants for similar thermodynamic reasons.[7] Histology analysis of their bones demonstrates that despite their small size, individuals of P. falconeri grew very slowly, reaching maturity at around 15 years of age (older than living elephants), with some individuals reaching a lifespan of at least 68 years, comparable to full-sized elephants.[8] Dental microwear suggests that P. falconeri was a mixed feeder (both browsing and grazing).[9]

Paleoenvironment

Sicily and Malta during the time of P. falconeri exhibited a depauperate fauna, with the only other terrestrial mammal species on the islands being the cat-sized giant dormouse Leithia (the largest dormouse ever) as well as the giant dormouse Maltamys, the otter Nesolutra, and the shrew Crocidura esuae which is possibly the ancestor of the living Sicilian shrew, C. sicula[10] though this is disputed[11] (the presence of a fox of the genus Vulpes has been suggested but is unconfirmed).[12][13] Sicily was also inhabited by a variety of bird species,[14] as well as frogs (Discoglossus, Bufotes, Hyla), lizards (Lacerta), snakes (Hierophis, Natrix), pond turtles, tortoises (including Solitudo[15] and Hermann's tortoise), and bats.[12]

Gallery

-

Reconstruction

-

Skeletons in Milan Natural History Museum

-

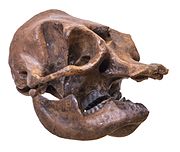

Skull atMUSE - Science Museum in Trento

References

- ^ ISSN 2571-550X.

- ^ Bonfiglio, L., Marra, A. C., Masini, F., Pavia, M., & Petruso, D. (2002). Pleistocene faunas of Sicily: a review. In W. H. Waldren, & J. A. Ensenyat (Eds.), World islands in prehistory: international insular investigations. British Archaeological Reports, International Series, 1095, 428–436.

- S2CID 235477150.

- ^ Busk, G. (1867). Description of the remains of three extinct species of elephant, collected by Capt. Spratt, C.B.R.N., in the ossiferous cavern of Zebbug, in the island of Malta. Transactions of the Zoological Society of London, 6: 227–306.

- ^ Palombo, M.R. (2001). Endemic elephants of the Mediterranean Islands: knowledge, problems and perspectives. The World of Elephants, Proceedings of the 1st International Congress (October 16–20, 2001, Rome): 486–491.

- ^ S2CID 181855906.

- ^ .

- PMID 34819557.

- S2CID 31931880.

- ISSN 1594-7629.)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - .

- ^ a b Bonfiglio, L., Marra, A. C., Masini, F., Pavia, M., & Petruso, D. (2002). Pleistocene faunas of Sicily: a review. In W. H. Waldren, & J. A. Ensenyat (Eds.), World islands in prehistory: international insular investigations. British Archaeological Reports, International Series, 1095, 428–436.

- .

- (PDF) from the original on 2023-07-16.

- ISSN 0024-4082.