Paleo-Hebrew alphabet

| Paleo-Hebrew | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | |

Time period | c. 1000 BCE – 135 CE |

| Direction | Right-to-left script |

| Language | Biblical Hebrew |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

Child systems | |

Sister systems | |

| ISO 15924 | |

Unicode range | U+10900–U+1091F |

| History of the alphabet | ||

|---|---|---|

|

||

|

||

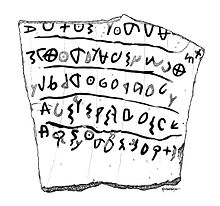

The Paleo-Hebrew script (Hebrew: הכתב העברי הקדום), also Palaeo-Hebrew, Proto-Hebrew or Old Hebrew, is the writing system found in inscriptions of Canaanite languages (incl. pre-Biblical and Biblical Hebrew) from the region of Southern Canaan, also known as biblical Israel and Judah. It is considered to be the script used to record the original texts of the Hebrew Bible due to its similarity to the Samaritan script, as the Talmud stated that the Hebrew ancient script was still used by the Samaritans.[1] The Talmud described it as the "Libona'a script" (Aramaic לִיבּוֹנָאָה Lībōnāʾā), translated by some as "Lebanon script".[1][2] Use of the term "Paleo-Hebrew alphabet" is due to a 1954 suggestion by Solomon Birnbaum, who argued that "[t]o apply the term Phoenician [from Northern Canaan, today's Lebanon] to the script of the Hebrews [from Southern Canaan, today's Israel-Palestine] is hardly suitable".[3] The Paleo-Hebrew and Phoenician alphabets are two slight regional variants of the same script.

The first Paleo-Hebrew inscription identified in modern times was the

Like the

By the 5th century BCE, among

History

Origins

The Paleo-Hebrew and Phoenician alphabets developed in the wake of the

The earliest known inscription in the Paleo-Hebrew script is the

The script on the Zayit Stone and Gezer Calendar are an earlier form than the classical Paleo-Hebrew of the 8th century and later; this early script is almost identical to the early Phoenician script on the 9th-century Ahiram sarcophagus inscription. By the 8th century, a number of regional characteristics begin to separate the script into a number of national alphabets, including the Israelite (Israel and Judah), Moabite (Moab and Ammon), Edomite, Phoenician and Old Aramaic scripts.

Linguistic features of the

The oldest inscriptions identifiable as Biblical Hebrew have long been limited to the 8th century BCE. In 2008, however, a potsherd (ostracon) bearing an inscription was excavated at Khirbet Qeiyafa which has since been interpreted as representing a recognizably Hebrew inscription dated to as early as the 10th century BCE. The argument identifying the text as Hebrew relies on the use of vocabulary.[14]

From the 8th century onward, Hebrew epigraphy becomes more common, showing the gradual spread of literacy among the people of the Kingdom of Israel and the Kingdom of Judah; the oldest portions of the Hebrew Bible, although transmitted via the recension of the Second Temple period, are also dated to the 8th century BCE.

Use in the Israelite kingdoms

The Paleo-Hebrew alphabet was in common use in the kingdoms of Israel and Judah throughout the 8th and 7th centuries BCE. During the 6th century BCE, the time of the

The Samaritans, who remained in the Land of Israel, continued to use their variant of the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet, called the Samaritan script.[16] After the fall of the Persian Empire, Jews used both scripts before settling on the Assyrian form.

The Paleo-Hebrew script evolved by developing numerous cursive features, the

Decline and late survival

After the Babylonian capture of Judea, when most of the nobles were taken into exile, the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet continued to be used by the people who remained. One example of such writings are the 6th-century BCE jar handles from Gibeon, on which the names of winegrowers are inscribed. Beginning from the 5th century BCE onward, the Aramaic language and script became an official means of communication. Paleo-Hebrew was still used by scribes and others.

The Paleo-Hebrew script was retained for some time as an archaizing or conservative mode of writing. It is found in certain texts of the

Legacy

Samaritan alphabet

The paleo-Hebrew alphabet continued to be used by the

Talmud

The

A third opinion

Contemporary use

Use of Proto-Hebrew in modern Israel is negligible, but it is found occasionally in nostalgic or pseudo-archaic examples, e.g. on the

be blessed with children").Archaeology

In 2019, the

Table of letters

Phoenician or Paleo-Hebrew characters were never standardised and are found in numerous variant shapes. A general tendency of more cursive writing can be observed over the period of c. 800 BCE to 600 BCE. After 500 BCE, it is common to distinguish the script variants by names such as "Samaritan", "Aramaic", etc.

There is no difference in "Paleo-Hebrew" vs. "Phoenician" letter shapes. The names are applied depending on the language of the inscription, or if that cannot be determined, of the coastal (Phoenician) vs. highland (Hebrew) association (c.f. the Zayit Stone abecedary).

| Letter | Name[35] | Meaning | Phoneme | Origin | Corresponding letter in | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image | Text | Samaritan

|

Square | |||||||||||

| 𐤀 | ʾālep | head of cattle (אלף) | ʾ [ʔ] | 𓃾 | ࠀ | א | ||||||||

| 𐤁 | bēt | house (בית) | b [b] | 𓉐 | ࠁ | ב | ||||||||

| 𐤂 | gīmel | camel (גמל) | g [ɡ] | 𓌙 | ࠂ | ג | ||||||||

| 𐤃 | dālet | door (דלת) | d [ d ]

|

𓇯 | ࠃ | ד | ||||||||

| 𐤄 | hē | jubilation/window[36] | h [h] | 𓀠? | ࠄ | ה | ||||||||

| 𐤅 | wāw | hook (וו) | w [w] | 𓏲 | ࠅ | ו | ||||||||

| 𐤆 | zayin | weapon (זין) | z [z] | 𓏭 | ࠆ | ז | ||||||||

| 𐤇 | ḥēt(?) | courtyard/thread[36] | ḥ [ħ] | 𓉗/𓈈? | ࠇ | ח | ||||||||

| 𐤈 | ṭēt | wheel (?)[37] | ṭ [tˤ] | ? | ࠈ | ט | ||||||||

| 𐤉 | yōd | arm, hand (יד) | y [j] | 𓂝 | ࠉ | י | ||||||||

| 𐤊 | kāp | palm of a hand (כף) | k [k] | 𓂧 | ࠊ | כ, ך | ||||||||

| 𐤋 | lāmed | goad (למד)[38] | l [ l ]

|

𓌅 | ࠋ | ל | ||||||||

| 𐤌 | mēm | water (מים) | m [m] | 𓈖 | ࠌ | מ, ם | ||||||||

| 𐤍 | nūn | fish (נון)[39] | n [ n ]

|

𓆓 | ࠍ | נ, ן | ||||||||

| 𐤎 | sāmek | pillar, support (סמך)[40] | s [s] | 𓊽 | ࠎ | ס | ||||||||

| 𐤏 | ʿayin | eye (עין) | ʿ [ʕ] | 𓁹 | ࠏ | ע | ||||||||

| 𐤐 | pē | mouth (פה) | p [p] | 𓂋 | ࠐ | פ, ף | ||||||||

| 𐤑 | ṣādē | ?[41] | ṣ [sˤ] | ? | ࠑ | צ, ץ | ||||||||

| 𐤒 | qōp | ?[42] | q [q] | ? | ࠒ | ק | ||||||||

| 𐤓 | rēš | head (ראש) | r [ r ]

|

𓁶 | ࠓ | ר | ||||||||

| 𐤔 | šīn | tooth (שין) | š [ʃ] | 𓌓 | ࠔ | ש | ||||||||

| 𐤕 | tāw | mark, sign (תו) | t [ t ]

|

𓏴 | ࠕ | ת | ||||||||

Unicode

The Unicode block Phoenician (U+10900–U+1091F) is intended for the representation of, apart from the Phoenician alphabet, text in Palaeo-Hebrew, Archaic Phoenician, Early Aramaic, Late Phoenician cursive, Phoenician papyri, Siloam Hebrew, Hebrew seals, Ammonite, Moabite, and Punic.

| Phoenician[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1090x | 𐤀 | 𐤁 | 𐤂 | 𐤃 | 𐤄 | 𐤅 | 𐤆 | 𐤇 | 𐤈 | 𐤉 | 𐤊 | 𐤋 | 𐤌 | 𐤍 | 𐤎 | 𐤏 |

| U+1091x | 𐤐 | 𐤑 | 𐤒 | 𐤓 | 𐤔 | 𐤕 | 𐤖 | 𐤗 | 𐤘 | 𐤙 | 𐤚 | 𐤛 | 𐤟 | |||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

See also

- Ancient Hebrew writings

- Ancient North Arabian

- Biblical Hebrew orthography

- History of the Hebrew alphabet

- Proto-Canaanite alphabet

- Proto-Sinaitic script

References

- ^ a b c d Sanhedrin (tractate) 21b: "אמר מר זוטרא ואיתימא מר עוקבא בתחלה ניתנה תורה לישראל בכתב עברי ולשון הקודש חזרה וניתנה להם בימי עזרא בכתב אשורית ולשון ארמי ביררו להן לישראל כתב אשורית ולשון הקודש והניחו להדיוטות כתב עברית ולשון ארמי. מאן הדיוטות אמר רב חסדא כותאי מאי כתב עברית אמר רב חסדא כתב ליבונאה" (translated: "Mar Zutra says, and some say that it is Mar Ukva who says: Initially, the Torah was given to the Jewish people in Ivrit script, and the sacred tongue, Hebrew. It was given to them again in the days of Ezra in Ashurit script and the Aramaic tongue. The Jewish people selected Ashurit script and the sacred tongue for the Torah scroll and left Ivrit script and the Aramaic tongue for the commoners. Who are these commoners? Rav Chisda said: The Samaritans [Kutim]. What is Ivrit script? Rav Chisda says: Lebanon script.")

- ^ This name is most likely derived from Lubban, i.e. the script is called "Libanian" (of Lebanon), although it has also been suggested that the name is a corrupted form of "Neapolitan", i.e. of Nablus. James A. Montgomery, The Samaritans, the earliest Jewish sect (1907), p. 283.

- ^ The Hebrew scripts, Volume 2, Salomo A. Birnbaum, Palaeographia, 1954, "To apply the term Phoenician to the script of the Hebrews is hardly suitable. I have therefore coined the term Palaeo-Hebrew."

- ^ Avigad, N. (1953). The Epitaph of a Royal Steward from Siloam Village. Israel Exploration Journal, 3(3), 137–152: "The inscription discussed here is, in the words of its discoverer, the first 'authentic specimen of Hebrew monumental epigraphy of the period of the Kings of Judah', for it was discovered ten years before the Siloam tunnel inscription. Now, after its decipherment, we may add that it is (after the Moabite Stone and the Siloam tunnel inscription) the third longest monumental inscription in Hebrew and the first known text of a Hebrew sepulchral inscription from the pre-Exilic period."

- ^ Clermont-Ganneau, 1899, Archaeological Researches In Palestine 1873–1874, Vol 1, p. 305: "The most important of these discoveries is certainly that which I had the good fortune to make of two large ancient Hebrew inscriptions in Phoenician letters... I may observe, by the way, that the discovery of these two texts was made long before that of the inscription in the tunnel, and therefore, though people in general do not seem to recognise this fact, it was the first which enabled us to behold an authentic specimen of Hebrew monumental epigraphy of the period of the Kings of Judah."

- ^ Millard, A. (1993), Reviewed Work: Ancient Hebrew Inscriptions. Corpus and Concordance by G. I. Davies, M. N. A. Bockmuehl, D. R. de Lacey, A. J. Poulter, The Journal of Theological Studies, 44(1), new series, 216–219: "...every identifiable Hebrew inscription dated before 200 BC... First ostraca, graffiti, and marks are grouped by provenance. This section contains more than five hundred items, over half of them ink-written ostraca, individual letters, receipts, memoranda, and writing exercises. The other inscriptions are names scratched on pots, scribbles of various sorts, which include couplets on the walls of tombs near Hebron, and letters serving as fitters' marks on ivories from Samaria.... The seals and seal impressions are set in the numerical sequence of Diringer and Vattioni (100.001–100.438). The pace of discovery since F. Vattioni issued his last valuable list (Ί sigilli ebraici III', AnnaliAnnali dell'Istituto Universitario Orientate di Napoli 38 (1978), 227—54) means the last seal entered by Davies is 100.900. The actual number of Hebrew seals and impressions is less than 900 because of the omission of those identified as non-Hebrew which previous lists counted. A further reduction follows when duplicate seal impressions from different sites are combined, as cross references in the entries suggest... The Corpus ends with 'Royal Stamps' (105.001-025, the Imlk stamps), '"Judah" and "Jerusalem" Stamps and Coins' (106.001-052), 'Other Official Stamps' (107.001), 'Inscribed Weights' (108.001-056) and 'Inscribed Measures' (109.001,002).... most seals have no known provenance (they probably come from burials)... Even if the 900 seals are reduced by as much as one third, 600 seals is still a very high total for the small states of Israel and Judah, and most come from Judah. It is about double the number of seals known inscribed in Aramaic, a language written over a far wider area by officials of great empires as well as by private persons.

- ISBN 978-0-521-82999-1.

This sequel to my Ancient Hebrew Inscriptions includes mainly inscriptions (about 750 of them) which have been published in the past ten years. The aim has been to cover all publications to the end of 2000. A relatively small number of the texts included here were published earlier but were missed in the preparation of AHI. The large number of new texts is not due, for the most part, to fresh discoveries (or, regrettably, to the publication of a number of inscriptions that were found in excavations before 1990), but to the publication of items held in private collections and museums.

- ^ Feldman (2010)

- ^ Shanks (2010)

- ISBN 978-0-8147-3654-8. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

By 1000 B.C.E., however, we see Phoenician writings [..]

- ^ Israel Finkelstein & Benjamin Sass, The West Semitic Alphabetic Inscriptions, Late Bronze II to Iron IIA: Archeological Context, Distribution and Chronology, HeBAI 2 (2013), pp. 149–220, see p. 189: "From the available evidence Hebrew appears to be the first regional variant to arise in the West Semitic alphabet – in late Iron IIA1; the scripts of the neighbouring peoples remain undifferentiated. It is only up to a century later, in early Iron IIB, that the distinct characteristics in the alphabets of Philistia, Phoenicia, Aram, Ammon and Moab develop."

- ^ Naveh, Joseph (1987), "Proto-Canaanite, Archaic Greek, and the Script of the Aramaic Text on the Tell Fakhariyah Statue", in Miller; et al. (eds.), Ancient Israelite Religion.

- ISBN 978-0-19-104448-9.

[...] scribes wrote in Paleo-Hebrew, a local variant of the Phoenician alphabetic script [...]

- ^ On January 10, 2010, the University of Haifa issued a press release stating that the text "uses verbs that were characteristic of Hebrew, such as ‘śh (עשה) ("did") and ‘bd (עבד) ("worked"), which were rarely used in other regional languages. Particular words that appear in the text, such as almanah ("widow") are specific to Hebrew and are written differently in other Canaanite languages. "Most ancient Hebrew biblical inscription deciphered". University of Haifa. January 10, 2010. Archived from the original on October 5, 2011. Retrieved November 5, 2011. See also: "Qeiyafa Ostracon Chronicle". Khirbet Qeiyafa Archaeological Project. Archived from the original on October 2, 2011. Retrieved November 5, 2011., "The keys to the kingdom". Haaretz.com. 6 May 2011. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ISBN 0-19-815402-X)

- ISBN 0-521-55634-1.

- ^ An illustration of the Siloam script is available at this link.

- ^ An illustration of a tomb inscription said to be scratched onto an ossuary to identify the decedent is available here. An article describing the ossuaries Zvi Greenhut excavated from a burial cave in the south of Jerusalem can be found in Jerusalem Perspective (July 1, 1991), with links to other articles.

- ^ Another tomb inscription is believed to be from the tomb of Shebna, an official of King Hezekiah. An illustration of the inscription may be viewed, but it is too large to be placed inline.

- ^ An illustration of the Lachish script is available at this link.

- ^ See Worker's appeal to governor.

- ^ The conduct complained about is contrary to Exodus 22, which provides:"If you take your neighbor's garment in pledge, you must return it to him before the sun sets; it is his only clothing, the sole covering for his skin. In what else shall he sleep?"

- ^ Dead Sea Scrolls Digital Library.

- ^ e.g. File:Psalms Scroll.jpg

- ^ a b c Sanhedrin 22a

- ^ a b c Jerusalem Talmud, Megillah 1:8.

- ^ Zevachim 62a

- ^ Megillah 3a

- ^ Shabbat 104a

- ^ Exodus 27, 10

- ^ Rabbeinu Chananel on Sanhedrin 22a

- ^ Maimonides. "Mishne Torah Hilchos Stam 1:19".

- ^ This is in imitation of the "Yehud coinage" minted in the Persian period. Yigal Ronen, "The Weight Standards of the Judean Coinage in the Late Persian and Early Ptolemaic Period", Near Eastern Archaeology 61, No. 2 (Jun., 1998), 122–126.

- ^ What's in a Name... - Israel Antiquities Authority (1 April 2019)

- ^ after Fischer, Steven R. (2001). A History of Writing. London: Reaction Books. p. 126.

- ^ a b The letters he and ḥēt continue three Proto-Sinaitic letters, ḥasir "courtyard", hillul "jubilation" and ḫayt "thread". The shape of ḥēt continues ḥasir "courtyard", but the name continues ḫayt "thread". The shape of he continues hillul "jubilation" but the name means "window".[citation needed] see: He (letter)#Origins.

- ^ The glyph was taken to represent a wheel, but it possibly derives from the hieroglyph nefer hieroglyph 𓄤 and would originally have been called tab טוב "good".

- ^ The root l-m-d mainly means "to teach", from an original meaning "to goad". H3925 in Strong's Exhaustive Concordance to the Bible, 1979.

- ^ the letter name nūn is a word for "fish", but the glyph is presumably from the depiction of a snake, which would point to an original name נחש "snake".

- ^ H5564 in Strong's Exhaustive Concordance to the Bible, 1979.

- ^ the letter name may be from צד "to hunt".

- ^ "The old explanation, which has again been revived by Halévy, is that it denotes an 'ape,' the character Q being taken to represent an ape with its tail hanging down. It may also be referred to a Talmudic root which would signify an 'aperture' of some kind, as the 'eye of a needle,' [...] Lenormant adopts the more usual explanation that the word means a 'knot'." Isaac Taylor, History of the Alphabet: Semitic Alphabets, Part 1, 2003.

Further reading

- "Alphabet, Hebrew". ISBN 965-07-0665-8

- Feldman, Rachel (2010). "Most ancient Hebrew biblical inscription deciphered". Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- Shanks, Hershel (2010). "Oldest Hebrew Inscription Discovered in Israelite Fort on Philistine Border". Biblical Archaeology Review. 36 (2): 51–56. Archived from the original on 2012-02-29. Retrieved 2020-06-20.