Palestinian nationalism

| Part of a series on |

| Palestinians |

|---|

|

| Demographics |

| Politics |

|

| Religion / religious sites |

|

Culture |

|

| List of Palestinians |

Palestinian nationalism is the

In the broader context of the

Origins and starting points

Zachary J. Foster argued in a 2015 Foreign Affairs article that "based on hundreds of manuscripts, Islamic court records, books, magazines, and newspapers from the Ottoman period (1516–1918), it seems that the first Arab to use the term "Palestinian" was Farid Georges Kassab, a Beirut-based Orthodox Christian." He explained further that Kassab’s 1909 book Palestine, Hellenism, and Clericalism noted in passing that "the Orthodox Palestinian Ottomans call themselves Arabs, and are in fact Arabs", despite describing the Arabic speakers of Palestine as Palestinians throughout the rest of the book."[4] The Palestinian Arab Christian Falastin newspaper had addressed its readers as Palestinians since its inception in 1911 during the Ottoman period.[5][6]

Foster later revised his view in a 2016 piece published in Palestine Square, arguing that already in 1898

In his 1997 book, Palestinian Identity: The Construction of Modern National Consciousness, historian

Israeli historian

In his book The Israel–Palestine Conflict: One Hundred Years of War, James L. Gelvin states that "Palestinian nationalism emerged during the interwar period in response to Zionist immigration and settlement."[16] However, this does not make Palestinian identity any less legitimate: "The fact that Palestinian nationalism developed later than Zionism and indeed in response to it does not in any way diminish the legitimacy of Palestinian nationalism or make it less valid than Zionism. All nationalisms arise in opposition to some "other." Why else would there be the need to specify who you are? And all nationalisms are defined by what they oppose."[16]

Bernard Lewis argues it was not as a Palestinian nation that the Palestinian Arabs of the Ottoman Empire objected to Zionists, since the very concept of such a nation was unknown to the Arabs of the area at the time and did not come into being until later. Even the concept of Arab nationalism in the Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire "had not reached significant proportions before the outbreak of World War I."[17]

Late Ottoman context

The collapse of the

Under the Ottomans, Palestine's Arab population mostly saw themselves as Ottoman subjects. In the 1830s however, Palestine was occupied by the Egyptian vassal of the Ottomans,

While Arab nationalism, at least in an early form, and Syrian nationalism were the dominant tendencies along with continuing loyalty to the Ottoman state, Palestinian politics were marked by a reaction to foreign predominance and the growth of foreign immigration, particularly Zionist.[20]

The Egyptian occupation of Palestine in the 1830s resulted in the destruction of

In 1887 the

Michelle Compos records that "Later, after the founding of Tel Aviv in 1909, conflicts over land grew in the direction of explicit national rivalry."[23] Zionist ambitions were increasingly identified as a threat by Palestinian leaders, while cases of purchase of lands by Zionist settlers and the subsequent eviction of Palestinian peasants aggravated the issue.

The programmes of four Palestinian nationalist societies jamyyat al-Ikha’ wal-‘Afaf (Brotherhood and Purity), al-jam’iyya al-Khayriyya al-Islamiyya (Islamic Charitable Society), Shirkat al-Iqtissad al-Falastini al-Arabi (lit. Arab Palestinian Economic Association) and Shirkat al-Tijara al-Wataniyya al-Iqtisadiyya (lit. National Economic Trade Association) were reported in the newspaper

British Mandate period

Nationalist groups built around notables

Palestinian Arab A’ayan ("Notables") were a group of urban elites at the apex of the Palestinian socio-economic pyramid where the combination of economic and political power dominated Palestinian Arab politics throughout the British Mandate period. The dominance of the A’ayan had been encouraged and utilised during the Ottoman period and later, by the British during the Mandate period, to act as intermediaries between the authority and the people to administer the local affairs of Palestine.

Al-Husseini

The

The Husaynis later led resistance and propaganda movements against the

Nashashibi

The

Tuqan

The

Abd al-Hadi

Khalidiy, al-Dajjani, al-Shanti

Other A’ayan were the Khalidi family, al-Dajjani family, and the al-Shanti family. The views of the A’ayan and their allies largely shaped the divergent political stances of Palestinian Arabs at the time. In 1918, as the Palestinian Arab national movements gained strength in Jerusalem,

1918–1920 nationalist activity

Following the arrival of the British a number of Muslim-Christian Associations were established in all the major towns. In 1919 they joined together to hold the first Palestine Arab Congress in Jerusalem. Its main platforms were a call for representative government and opposition to the Balfour Declaration.

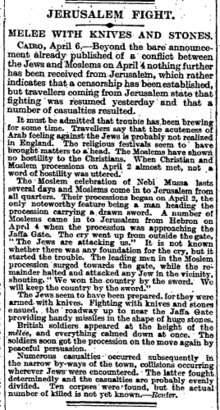

The

After the April riots an event took place that turned the traditional rivalry between the Husayni and Nashashibi clans into a serious rift,

Supreme Muslim Council under Hajj Amin (1921–1937)

The High Commissioner of Palestine, Herbert Samuel, as a counterbalance the Nashashibis gaining the position of Mayor of Jerusalem, pardoned Hajj Amīn and Aref al-Aref and established a Supreme Muslim Council (SMC), or Supreme Muslim Sharia Council, on 20 December 1921.[36] The SMC was to have authority over all the Muslim Waqfs (religious endowments) and Sharia (religious law) Courts in Palestine. The members of the Council were to be elected by an electoral college and appointed Hajj Amīn as president of the Council with the powers of employment over all Muslim officials throughout Palestine.[37] The Anglo American committee termed it a powerful political machine.[38]

The Hajj Amin rarely delegated authority, consequently most of the council's executive work was carried out by Hajj Amīn.[38] Nepotism and favoritism played a central part to Hajj Amīn's tenure as president of the SMC, Amīn al-Tamīmī was appointed as acting president when the Hajj Amīn was abroad, The secretaries appointed were ‘Abdallah Shafĩq and Muhammad al’Afĩfĩ and from 1928 to 1930 the secretary was Hajj Amīn's relative Jamāl al-Husaynī, Sa’d al Dīn al-Khaţīb and later another of the Hajj Amīn's relatives ‘Alī al-Husaynī and ‘Ajaj Nuwayhid, a Druze was an adviser.[38]

Politicisation of the Wailing Wall

It was during the British mandate period that politicisation of the Wailing Wall occurred.[39] The disturbances at the Wailing wall in 1928 were repeated in 1929, however the violence in the riots that followed, that left 116 Palestinian Arabs, 133 Jews dead and 339 wounded, were surprising in their intensity.[40]

Black Hand gang

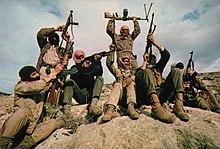

1936–1939 Arab revolt

The Great revolt 1936–1939 was an uprising by Palestinian Arabs in the British Mandate of Palestine in protest against mass Jewish immigration.

Muhammad Nimr al-Hawari, who had started his career as a devoted follower of Hajj Amin, broke with the influential Husayni family in the early 1940s.[46] The British estimated the strength of the al-Najjada paramilitary scout movement, led by Al-Hawari, at 8,000 prior to 1947.[47]

1937 Peel Report and its aftermath

The Nashashibis broke with the

The split in the ranks of the

Results

The revolt of 1936–1939 led to an imbalance of power between the Jewish community and the Palestinian Arab community, as the latter had been substantially disarmed.[48]

1947–1948 war

Al-Qadir moved to

1948–1964

In September 1948, the

The All-Palestine Government however lacked any significant authority and was in fact seated in Cairo. In 1959 it was officially merged into the

The

PLO until the First Intifada (1964–1988)

The

Defeat suffered by the Arab states in the June 1967 Six-Day War, brought the West Bank, East Jerusalem and the Gaza Strip under Israeli military control.

Yasser Arafat, claimed the

In 1974 the PLO called for an independent state in the territory of

In 1988, the PLO officially endorsed a two-state solution, with Israel and Palestine living side by side contingent on specific terms such as making East Jerusalem capital of the Palestinian state and giving Palestinians the right of return to land occupied by Palestinians prior to the 1948 and 1967 wars with Israel.[66]

First Intifada (1987–1993)

Local leadership vs. the PLO

The First Intifada (1987–1993) would prove another watershed in Palestinian nationalism, as it brought the Palestinians of the West Bank and Gaza to the forefront of the struggle. The Unified National Leadership of the Uprising (UNLU; Arabic al-Qiyada al Muwhhada) mobilised grassroots support for the uprising.[67]

In 1987 The Intifada caught the (PLO) by surprise, the leadership abroad could only indirectly influence the events.,[67] A new local leadership, the UNLU, emerged, comprising many leading Palestinian factions. The disturbances initially spontaneous soon came under local leadership from groups and organizations loyal to the PLO that operated within the Occupied Territories; Fatah, the Popular Front, the Democratic Front and the Palestine Communist Party.[68] The UNLU was the focus of the social cohesion that sustained the persistent disturbances.[69]

After

Emergence of Hamas

During the intifada Hamas breached the monopoly of the PLO as sole political representative of the Palestinian people.[72]

Peace process

Some Israelis had become tired of the constant violence of the First Intifada, and many were willing to take risks for peace.[73] Some wanted to realize the economic benefits in the new global economy. The Gulf War (1990–1991) did much to persuade Israelis that the defensive value of territory had been overstated, and that the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait psychologically reduced their sense of security.[74]

A renewal of the Israeli–Palestinian quest for peace began at the end of the Cold War as the United States took the lead in international affairs. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Western observers were optimistic, as Francis Fukuyama wrote in an article, titled "The End of History". The hope was that the end of the Cold War heralded the beginning of a new international order. President George H. W. Bush, in a speech on 11 September 1990, spoke of a "rare opportunity" to move toward a "New world order" in which "the nations of the world, east and west, north and south, can prosper and live in harmony," adding that "today the new world is struggling to be born".[75]

1993 Oslo Agreement

The demands of the local Palestinian and Israeli populations were somewhat differing from those of the Palestinian diaspora, which had constituted the main base of the PLO until then, in that they were primarily interested in

Palestinian National Authority (1993)

In 1993, with the transfer of increased control of Muslim holy sites in Jerusalem from Israel to the Palestinians, PLO chairman Yasser Arafat appointed Sulaiman Ja'abari as Grand Mufti. When he died in 1994, Arafat appointed Ekrima Sa'id Sabri. Sabri was removed in 2006 by Palestinian National Authority president Mahmoud Abbas, who was concerned that Sabri was involved too heavily in political matters. Abbas appointed Muhammad Ahmad Hussein, who was perceived as a political moderate.

Goals

Palestinian statehood

Proposals for a Palestinian state refer to the proposed establishment of an independent state for the Palestinian people in Palestine on land that was occupied by Israel since the Six-Day War of 1967 and prior to that year by Egypt (Gaza) and by Jordan (West Bank). The proposals include the Gaza Strip, which is controlled by the Hamas faction of the Palestinian National Authority, the West Bank, which is administered by the Fatah faction of the Palestinian National Authority, and East Jerusalem which is controlled by Israel under a claim of sovereignty.[76]

From the river to the sea

"From the river to the sea" is, and forms part of, a popular Palestinian political slogan. It references the land which lies between the

"Palestine from the river to the sea" was claimed as

Competing national, political, and religious loyalties

Pan-Arabism

Some groups within the PLO hold a more

Pan-Islamism

In a later repetition of these developments, the

By early Islamic thinkers, nationalism had been viewed as an ungodly ideology, substituting "the

See also

- Concepts and events:

- 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine

- 1948 Palestinian expulsion and flight

- Grand Mufti of Jerusalem – position created by the British military government in 1918

- Greater Palestine

- History of Palestine

- History of Palestinian nationality

- Israeli–Palestinian conflict

- Palestinian Declaration of Independence

- Palestinian government

- Palestinian political violence

- State of Palestine

- Timeline of the name "Palestine"

- Views of Palestinian statehood

- Individuals:

- Abd al-Qadir al-Husayni (1907–1948), military leader

- Khalil al-Sakakini(1878–1953), Christian teacher, scholar, poet, and Arab nationalist

- Musa al-Husayni (1853–1934), mayor of Jerusalem

- Yousef al-Khalidi (1829–1906), Ottoman politician and mayor of Jerusalem

- Zuheir Mohsen (1936–1979), pro-Syria PLO leader

References

- Palestinian National Charter of 1968. The Avalon Project has a copy here [1]

- ^ Joffe, Alex. "Palestinians and Internationalization: Means and Ends." Begin–Sadat Center for Strategic Studies. 26 November 2017. 28 November 2017.

- ^ "No UN Vote Can Deny the Palestinian People Their Right to Self Determination". The Huffington Post UK. 2 January 2015.

- ^ Foster, Zachary J. (6 October 2015). "What's a Palestinian?". Foreign Affairs – via www.foreignaffairs.com.

- ^ a b Harold M. Cubert (3 June 2014). The PFLP's Changing Role in the Middle East. Routledge. p. 36. Retrieved 31 December 2023.

That year, Al-Karmil was founded in Haifa 'with the purpose of opposing Zionist colonization...' and in 1911, Falastin began publication, referring to its readers, for the first time, as 'Palestinians'.

- ^ a b Neville J. Mandel (1976). The Arabs and Zionism Before World War I. University of California Press. p. 128. Retrieved 31 December 2023.

As befitted its name, Falastin regularly discussed questions to do with Palestine as if it were a distinct entity and, in writing against the Zionists, addressed its readers as "Palestinians".

- ^ a b Zachary Foster, "Who Was The First Palestinian in Modern History" Archived 29 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine The Palestine Square 18 February 2016

- ^ Khalidi, 1997, p. 18.

- ^ Khalidi, 1997, p. 149.

- ^ a b c Khalidi, 1997, p. 19–21.

- ISBN 0-292-70680-4p. 158

- ISBN 0-231-10515-0p. 32

- S2CID 162982234.

- ^ ISBN 0-674-01131-7pp. 6–11

- ^ Benny Morris, Righteous Victims, pp. 40–42 in the French edition.

- ^ a b Gelvin, 2005, pp. 92–93.

- ISBN 978-0-393-31839-5.

- ^ "The Year the Arabs Discovered Palestine", by Daniel Pipes, Jerusalem Post, 13 September 2000 [2]

- ISBN 0-691-11897-3p 123

- ^ Foreign predominance and the rise of Palestinian nationalism

- Google Book Search. 5 February 2009.

- Palestine: a study of Jewish, Arab, and British policies By Esco Foundation for Palestine, inc

- ^ Doumani, 1995, Chapter: Egyptian rule, 1831-1840.

- ISBN 0-7425-5842-8, p. 70

- ISBN 0-7425-4639-X, p. 48

- ISBN 0-85664-635-0p 33

- ^ a b Illan Pappe. "The Rise and Fall of the Husainis (Part 1)". jerusalemquarterly.org. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007.

- ^ Jerusalemites Archived 22 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine Families of Jerusalem and Palestine

- ISBN 0-275-94576-6p 290

- ISBN 0-521-55632-5p 103

- ISBN 0-520-20768-8p 119

- ISBN 0-7914-0708-Xp 79

- ^ "Rediscovering Palestine". escholarship.org.

- ^ Porath, chapter 2

- ^ Eliezer Tauber, The Formation of Modern Iraq and Syria, Routledge, London 1994 pp.105-109

- ^ Eliezer Tauber, The Formation of Modern Iraq and Syria, Routledge, London 1994 p.102

- ^ Palin Report, pp. 29-33. Cited Huneidi p.37.

- ISBN 978-0-8133-3489-9

- ^ UN Doc Archived 20 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ ISBN 90-04-07929-7pp 66-67

- ^ Jerusalemite Institute of Jerusalem Studies: Heritage, Nationalism and the Shifting Symbolism of the Wailing Wall by Simone Ricca

- ^ 1929 Palestine riots

- Sandra Marlene Sufian and Mark LeVine (2007) -Remembering Jewish-Arab Contact and Conflict by Michelle Compos p 54

- San Francisco Chronicle, 9 August 2005, "A Time of Change; Israelis, Palestinians and the Disengagement"

- NA 59/8/353/84/867n, 404 Wailing Wall/279 and 280, Archdale Diary and Palestinian Police records.

- ISBN 0-275-97902-4p 11

- ^ Sylvain Cypel (2006) p 340

- ^ Abdullah Franji (1983) p 87

- ^ Levenberg, 1993, p. 6.

- ISBN 0-85303-672-1p. 71

- ISBN 978-0-300-12696-9pp. 88–89.

- ^ Khalaf, 1991, p 143.

- ^ a b Ted Swedenburg. (1988)

- ^ Morris, Benny. The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited (Cambridge, 2004), p. 588. qtd. by Susser.

- . 7 March 1991. 17 March 2009.

- Haaretz "The real Nakba", Shlomo Avineri, 9 May 2008

- Shlaim, Avi (reprint 2004) The Politics of Partition: King Abdullah, the Zionists and Palestine 1921–1951, Oxford University Press ISBN 0-19-829459-Xp 104

- Morris, Benny, (second edition 2004 third printing 2006) The Birth Of The Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited, Cambridge University Press, .

- ^ al-Qadir dies at Qastal

- Morris, (2003), pp. 234–235.

- New York Times, "Arabs Win Kastel But Chief is Slain; Kader el-Husseini, a Cousin of Mufti, Falls as His Men Recapture Key Village", by Dana Adams Schmidt, 9 April 1948.

- Benveniśtî, (2002), p.111.

- ^ Gelber, Yoav (2001) pp 89–90

- ISBN 9781845190750– via Google Books.

- ISBN 9781851098422.

- ISBN 0-231-10515-0p 178

- ^ Khalidi (1998) p 180

- Danny Rubenstein, Haaretz; 6 June 2001

- ISBN 1-58234-049-8.

- ^ See articles 1, 2 and 3 in the Palestinian National Charter (1968) as published by The Avalon Project at Yale Law School

- ^ Helena Cobban,The Palestinian Liberation Organisation(Cambridge University Press, 1984) p.30

- ^ "Articles 2 and 23 of the Palestinian National Covenant".

- ^ Kurz (2006), p. 55

- ^ "1968: Karameh and the Palestinian revolt". Telegraph. 16 May 2002. Retrieved 3 September 2008.

- ^ Pollack (2002), p. 335

- ^ a b The PNC Program of 1974, 8 June 1974. On the site of MidEastWeb for Coexistence R.A. - Middle East Resources. Page includes commentary. Retrieved 5 December 2006.

- ^ Arab-Israeli Conflict Archived 28 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Encarta

- ISBN 0-8133-4048-9.

- ^ a b Yasser Arafat obituary Archived 11 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine, socialistworld.net (Committee for a Worker's International).

- ISBN 0-89608-363-2p 39

- ISBN 1-86064-098-2p 194

- ^ King Hussein, Address to the Nation, Amman, Jordan, 31 July 1988. The Royal Hashemit Court's tribute to King Hussein

- ISBN 0-253-33377-6p 48

- ISBN 0-231-11675-6p 1

- ^ The Israel-Palestine Conflict, James L. Gelvin

- ^ The Gulf Conflict 1990–1991: Diplomacy and War in the New World Order, Lawrence Freedman and Efraim Karsh

- ^ President Bush's speech to Congress Archived 31 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine al-bab.com

- ^ "Olmert: Israel must quit East Jerusalem and Golan". Haaretz. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- ISBN 978-0-307-43281-0.

Only two years ago he [Saddam Hussein] declared on Iraqi television: 'Palestine is Arab and must be liberated from the river to the sea and all the Zionists who emigrated to the land of Palestine must leave.'

- ISBN 978-0-7456-4243-7.

One exception was Faysal al- Husayni, who stated in his 2001 Beirut speech: 'We may lose or win [tactically] but our eyes will continue to aspire to the strategic goal, namely, to Palestine from the river to the sea.'

- ISBN 978-0-230-10687-1.

Thus, the MAB slogan 'Palestine must be free, from the river to the sea' is now ubiquitous in anti-Israeli demonstrations in the UK ...

- ^ "From the river to the sea, Jews and Arabs must forge a shared future". The Guardian. 23 May 2021.

- ^ "The Real Meaning of "From the River to the Sea"". The Jewish Journal. 16 June 2021.

- ^ "United Nations Maintenance Page". unispal.un.org. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015.

- ^ "The Covenant of the Islamic Resistance Movement (Hamas)". MidEast Web. 18 August 1988.

- ^ Nassar, Maha (3 December 2018). "'From The River To The Sea' Doesn't Mean What You Think It Means". The Forward. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

Bibliography

- Antonius, George (1938) The Arab Awakening: The Story of the Arab National Movement. Hamish Hamilton. (1945 edition)

- Benvenisti, Meron (1998) City of Stone: The Hidden History of Jerusalem, University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-20768-8

- Cypel, Sylvain (2006) Walled: Israeli Society at an Impasse, Other Press, ISBN 1-59051-210-3

- ISBN 0-86232-195-6

- Hoveyda, Fereydoun of National Committee on American Foreign Policy (2002) The Broken Crescent: The "Threat" of Militant Islamic Fundamentalism, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0-275-97902-4

- Khalaf, Issa (1991) Politics in Palestine: Arab Factionalism and Social Disintegration, 1939–1948, SUNY Press ISBN 0-7914-0707-1

- Khalidi, Rashid (1997) Palestinian Identity: The Construction of Modern National Consciousness, Columbia University Press, ISBN 0-231-10515-0

- Kimmerling, Baruch and Migdal, Joel S, (2003) The Palestinian People: A History, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-01131-7

- Kupferschmidt, Uri M. (1987) The Supreme Muslim Council: Islam Under the British Mandate for Palestine ISBN 90-04-07929-7

- Kurz, Anat N. (2006-01-30). Fatah and the Politics of Violence: The Institutionalization of a Popular Struggle. Sussex Academic Press. p. 228. ISBN 1-84519-032-7

- Lassner, Jacob (2000) The Middle East Remembered: Forged Identities, Competing Narratives, Contested Spaces, University of Michigan Press, ISBN 0-472-11083-7

- Levenberg, Haim (1993). Military Preparations of the Arab Community in Palestine: 1945–1948. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-7146-3439-5

- Mishal, Shaul and Sela, Avraham (2000) The Palestinian Hamas: Vision, Violence, and Coexistence, Columbia University Press, ISBN 0-231-11675-6

- Morris, Benny (2008) 1948: A History of the First Arab–Israeli War. Yale University Press ISBN 978-0-300-12696-9

- Morris, Benny, (second edition 2004 third printing 2006) ISBN 0-521-00967-7

- Sufian, Sandra Marlene, and LeVine, Mark (2007) Reapproaching borders: new perspectives on the study of Israel-Palestine, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 0-7425-4639-X

- Swedenburg, Ted (1988) "The Role of the Palestinian Peasantry in the Great Revolt 1936–1939", in Islam, Politics, and Social Movements, edited by Edmund Burke III and Ira Lapidus. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-8021-3936-1pp 177–181

- Pappé Ilan (2004) A History of Modern Palestine: One Land, Two Peoples, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-55632-5

- Peretz, Don (1994) The Middle East Today, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0-275-94576-6

- Provence, Michael (2005) The Great Syrian Revolt and the Rise of Arab Nationalism, University of Texas Press, ISBN 0-292-70680-4

- Shlaim, Avi (reprint 2004) The Politics of Partition; King Abdullah, the Zionists and Palestine, 1921–1951, Oxford University Press ISBN 0-19-829459-X

- Winter, Dave (1999) Israel Handbook: With the Palestinian Authority Areas, Footprint Travel Guides, ISBN 1-900949-48-2