Palinuro Seamount

| Palinuro | |

|---|---|

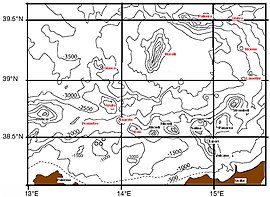

Aeolian arc, including coastline and depth contour lines for every 500 meters. | |

| Summit depth | 70 m (230 ft) |

| Location | |

| Location | Tyrrhenian Sea |

| Coordinates | 39°29′04″N 14°49′44″E / 39.48444°N 14.82889°E[1] |

Palinuro Seamount is a seamount in the Tyrrhenian Sea. It is an elongated 50–70 km (31–43 mi) long complex of volcanoes north of the Aeolian Islands with multiple potential calderas. The shallowest point lies at 80–70 m (260–230 ft) depth and formed an island during past episodes of low sea level. Palinuro was active during the last 800,000 years and is likely the source for a 10,000 years old tephra layer in Italy. Ongoing seismicity occurs at the seamount, which may be a tsunami hazard. The volcanic activity may somehow relate to the subduction of the Ionian Sea farther east.

Diffuse

Geography and geomorphology

Palinuro lies north of the

The seamount is about 3 km (1.9 mi) high.

At least eight separate volcanoes make up Palinuro.

Geology

The

The seamount may be located at the margin between the oceanic Marsili basin to the south, and the

Composition

Dredging has yielded

Biology

Dense and large stands of

Small hydrothermal deposits with the shape of chimneys are covered by

Eruption history

Palinuro was active between 800,000 and 300,000 years ago.

The PL-1

Recent activity and hazards

Palinuro or its southeastern sector may still be active, as volcanic seismicity has been detected between Palinuro and the Calabrian coast.[50] Seismicity at low depths, perhaps linked to hydrothermal activity, has also been recorded.[51] Microearthquakes between 10–16 km (6.2–9.9 mi) depth may mark a melt storage zone.[52]

Volcanic edifices are often unstable and prone to

Hydrothermal activity and deposits

Diffuse

Hydrothermal activity is responsible for

References

- ^ a b Würtz 2015, p. 113.

- ^ a b c d e GVP 2022, General Information.

- ^ a b Ligi et al. 2014, p. 8.

- ^ Passaro et al. 2010, p. 135.

- ^ Würtz 2015, p. 143.

- ^ Milano, Passaro & Sprovieri 2012, p. 404.

- ^ a b c d Passaro et al. 2010, p. 131.

- ^ Innangi et al. 2016, p. 736.

- ^ a b c d Caratori Tontini, Cocchi & Carmisciano 2009, p. 11.

- ^ a b Passaro et al. 2010, p. 133.

- ^ Passaro et al. 2010, p. 139.

- ^ Marani & Gamberi 2004, p. 115.

- ^ a b Caratori Tontini, Cocchi & Carmisciano 2009, p. 12.

- ^ a b Passaro et al. 2010, p. 132.

- ^ Ligi et al. 2014, p. 14.

- ^ a b c Milano, Passaro & Sprovieri 2012, p. 412.

- ^ Innangi et al. 2016, p. 738.

- ^ a b Milano, Passaro & Sprovieri 2012, p. 406.

- ^ a b Ligi et al. 2014, p. 15.

- ^ Milano, Passaro & Sprovieri 2012, p. 408.

- ^ Caratori Tontini, Cocchi & Carmisciano 2009, p. 14.

- ^ Passaro et al. 2011, p. 231.

- ^ a b Petersen & Monecke 2009, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d Passaro et al. 2010, p. 130.

- ^ a b Ligi et al. 2014, p. 5.

- ^ Milano, Passaro & Sprovieri 2012, p. 403.

- ^ Cocchi et al. 2017, p. 9.

- ^ Gallotti et al. 2020, p. 3.

- ^ Cocchi et al. 2017, p. 2.

- ^ Cocchi et al. 2017, p. 3.

- ^ Passaro et al. 2011, p. 236.

- ^ Milano, Passaro & Sprovieri 2012, p. 413.

- ^ Innangi et al. 2016, p. 737.

- ^ Colantoni et al. 1981, p. M6.

- ^ Fanelli et al. 2017, p. 966.

- ^ a b Würtz 2015, pp. 156–157.

- ^ Rosli et al. 2018, p. 20.

- ^ Eckhardt et al. 1997, p. 184.

- ^ Kidd & Ármannson 1979, p. 72.

- ^ Hilpold et al. 2011, p. 535.

- ^ Würtz 2015, p. 14.

- ^ a b c Ligi et al. 2014, p. 19.

- ^ a b c Petersen et al. 2007.

- ^ Würtz 2015, p. 157.

- ^ Angiolillo et al. 2021, p. 17.

- ^ Passaro et al. 2010, p. 137.

- ^ Caratori Tontini, Cocchi & Carmisciano 2009, p. 15.

- ^ GVP 2022, Eruption History.

- ^ Siani et al. 2004, p. 2496.

- ^ Passaro et al. 2010, pp. 130–131.

- ^ a b Gallotti et al. 2020, p. 2.

- ^ Cocchi et al. 2017, p. 8.

- ^ Gallotti et al. 2020, p. 1.

- ^ Gallotti et al. 2020, p. 5.

- ^ Gallotti et al. 2020, p. 11.

- ^ Gallotti et al. 2020, p. 8.

- ^ a b Safipour et al. 2017, p. 4.

- ^ a b Würtz 2015, p. 156.

- ^ Petersen & Monecke 2009, p. 6.

- ^ Milano, Passaro & Sprovieri 2012, p. 409.

- ^ Ligi et al. 2014, p. 20.

- ^ Ligi et al. 2014, p. 21.

- ^ a b Milano, Passaro & Sprovieri 2012, p. 410.

- ^ Petersen & Monecke 2009, p. 26.

- ^ Eckhardt et al. 1997, p. 181.

- ^ Tufar 1991, p. 267.

- ^ Tufar 1991, p. 282.

- ^ Tufar 1991, p. 290.

- ^ Safipour et al. 2017, p. 2.

- ^ Iyer et al. 2012, p. 301.

- ^ Fuchs, Hannington & Petersen 2019, p. 796.

- ^ Ladenberger et al. 2015, p. 63.

- ^ Eckhardt et al. 1997, p. 195.

- ^ Eckhardt et al. 1997, pp. 179, 181.

- ^ Eckhardt et al. 1997, p. 186.

Sources

- Angiolillo, Michela; La Mesa, Gabriele; Giusti, Michela; Salvati, Eva; Di Lorenzo, Bianca; Rossi, Lorenzo; Canese, Simonepietro; Tunesi, Leonardo (1 September 2021). "New records of scleractinian cold-water coral (CWC) assemblages in the southern Tyrrhenian Sea (western Mediterranean Sea): Human impacts and conservation prospects". Progress in Oceanography. 197: 102656. ISSN 0079-6611.

- Caratori Tontini, F.; Cocchi, L.; Carmisciano, C. (13 February 2009). "Rapid 3-D forward model of potential fields with application to the Palinuro Seamount magnetic anomaly (southern Tyrrhenian Sea, Italy)". Journal of Geophysical Research. 114 (B2): B02103. ISSN 0148-0227.

- Cocchi, Luca; Passaro, Salvatore; Tontini, Fabio Caratori; Ventura, Guido (13 November 2017). "Volcanism in slab tear faults is larger than in island-arcs and back-arcs". Nature Communications. 8 (1): 1451. PMID 29129913.

- Colantoni, P.; Lucchini, F.; Rossi, P. L.; Sartori, R.; Savelli, C. (1 January 1981). "The Palinuro volcano and magmatism of the southeastern Tyrrhenian Sea (Mediterranean)". Marine Geology. 39 (1): M1–M12. ISSN 0025-3227.

- Eckhardt, J.-D.; Glasby, G. P.; Puchelt, H.; Berner, Z. (April 1997). "Hydrothermal manganese crusts from Enarete and Palinuro seamounts in the Tyrrhenian Sea". Marine Georesources & Geotechnology. 15 (2): 175–208. ISSN 1064-119X.

- Fanelli, Emanuela; Delbono, Ivana; Ivaldi, Roberta; Pratellesi, Marta; Cocito, Silvia; Peirano, Andrea (October 2017). "Cold-water coral Madrepora oculata in the eastern Ligurian Sea (NW Mediterranean): Historical and recent findings". Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems. 27 (5): 965–975. doi:10.1002/aqc.2751.

- Fuchs, Sebastian; Hannington, Mark D.; Petersen, Sven (1 August 2019). "Divining gold in seafloor polymetallic massive sulfide systems". Mineralium Deposita. 54 (6): 789–820. S2CID 198420762.

- Gallotti, G.; Passaro, S.; Armigliato, A.; Zaniboni, F.; Pagnoni, G.; Wang, L.; Sacchi, M.; Tinti, S.; Ligi, M.; Ventura, G. (15 October 2020). "Potential mass movements on the Palinuro volcanic chain (southern Tyrrhenian Sea, Italy) and consequent tsunami generation". Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research. 404: 107025. S2CID 225373895.

- "Palinuro". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- Hilpold, Andreas; Schönswetter, Peter; Susanna, Alfonso; Garcia-Jacas, Núria; Vilatersana, Roser (April 2011). "Evolution of the central Mediterranean Centaurea cineraria group (Asteraceae): Evidence for relatively recent, allopatric diversification following transoceanic seed dispersal". Taxon. 60 (2): 528–538. hdl:10261/50084.

- Innangi, Sara; Passaro, Salvatore; Tonielli, Renato; Milano, Girolamo; Ventura, Guido; Tamburrino, Stella (19 October 2016). "Seafloor mapping using high-resolution multibeam backscatter: The Palinuro Seamount (Eastern Tyrrhenian Sea)". Journal of Maps. 12 (5): 736–746. S2CID 131436997.

- Iyer, S. D.; Mehta, C. M.; Das, P.; Kalangutkar, N. G. (2012). "Seamounts-characteristics, formation, mineral deposits and biodiversity". Geologica Acta. 10 (3): 295–309. .

- Kidd, R. B.; Ármannson, H. (1 February 1979). "Manganese and iron micronodules from a volcanic seamount in the Tyrrhenian Sea". Journal of the Geological Society. 136 (1): 71–76. S2CID 128762375.

- Ladenberger, Anna; Demetriades, Alecos; Reimann, Clemens; Birke, Manfred; Sadeghi, Martiya; Uhlbäck, Jo; Andersson, Madelen; Jonsson, Erik (1 July 2015). "GEMAS: Indium in agricultural and grazing land soil of Europe — Its source and geochemical distribution patterns". Journal of Geochemical Exploration. 154: 61–80. ISSN 0375-6742.

- Ligi, Marco; Cocchi, Luca; Bortoluzzi, Giovanni; D’Oriano, Filippo; Muccini, Filippo; Caratori Tontini, Fabio; de Ronde, Cornel E. J.; Carmisciano, Cosmo (1 December 2014). "Mapping of Seafloor Hydrothermally Altered Rocks Using Geophysical Methods: Marsili and Palinuro Seamounts, Southern Tyrrhenian Sea". Economic Geology. 109 (8): 2103–2117. ISSN 0361-0128.

- Marani, MP; Gamberi, F (2004). "Distribuzione e natura della morfologia del vulcanismo sottomarino nel Mar Tirreno: l'arco e retro-arco". From Seafloor to Deep Mantle: Architecture of the Tyrrhenian Backarc Basin (PDF). Vol. 64. ISSN 0536-0242.

- Milano, G.; Passaro, S.; Sprovieri, M. (December 2012). "Present-day knowledge on the Palinuro Seamount (south-eastern Tyrrhenian Sea)". Bollettino di Geofisica Teorica ed Applicata. 53 (4): 403–416. doi:10.4430/bgta0042.

- Passaro, Salvatore; Milano, Girolamo; D'Isanto, Claudio; Ruggieri, Stefano; Tonielli, Renato; Bruno, Pier Paolo; Sprovieri, Mario; Marsella, Ennio (15 February 2010). "DTM-based morphometry of the Palinuro seamount (Eastern Tyrrhenian Sea): Geomorphological and volcanological implications". Geomorphology. 115 (1): 129–140. ISSN 0169-555X.

- Passaro, Salvatore; Milano, Girolamo; Sprovieri, Mario; Ruggieri, Stefano; Marsella, Ennio (15 February 2011). "Quaternary still-stand landforms and relations with flank instability events of the Palinuro Bank (southeastern Tyrrhenian Sea)". Quaternary International. 232 (1): 228–237. ISSN 1040-6182.

- Petersen, S.; Augustin, N.; de Benedetti, A.; Esposito, A.; Gaertner, A.; Gemmell, B.; Gibson, H.; He, G.; Huegler, M.; Kleeberg, R.; Kuever, J.; Kummer, N. A.; Lackschewitz, K.; Lappe, F.; Monecke, T.; Perrin, K.; Peters, M.; Sharpe, R.; Simpson, K.; Smith, D.; Wan, B. (1 December 2007). Drilling of Submarine Shallow-water Hydrothermal Systems in Volcanic Arcs of the Tyrrhenian Sea, Italy. American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting 2007. AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts. Vol. 2007. pp. V34B–01. Bibcode:2007AGUFM.V34B..01P.

- Petersen, Sven; Monecke, Thomas, eds. (June 2009). FS METEOR Fahrtbericht / Cruise Report M73/2 Shallow drilling of hydrothermal sites in the Tyrrhenian Sea (PALINDRILL) (PDF) (Report). Berichte aus dem Leibniz-Institut für Meereswissenschaften an der Christian-Albrechts-Universität zu Kiel. Vol. 30. ISSN 1614-6298. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- Rosli, Norliana; Leduc, Daniel; Rowden, Ashley A.; Probert, P. Keith (1 March 2018). "Review of recent trends in ecological studies of deep-sea meiofauna, with focus on patterns and processes at small to regional spatial scales". Marine Biodiversity. 48 (1): 13–34. S2CID 4351098.

- Safipour, Roxana; Hölz, Sebastian; Halbach, Jesse; Jegen, Marion; Petersen, Sven; Swidinsky, Andrei (6 October 2017). "A self-potential investigation of submarine massive sulfides: Palinuro Seamount, Tyrrhenian Sea" (PDF). Geophysics. 82 (6): A51–A56. ISSN 0016-8033.

- Siani, Giuseppe; Sulpizio, Roberto; Paterne, Martine; Sbrana, Alessandro (1 December 2004). "Tephrostratigraphy study for the last 18,000 14C years in a deep-sea sediment sequence for the South Adriatic". Quaternary Science Reviews. 23 (23–24): 2485–2500. ISSN 0277-3791.

- Tufar, Werner (1991). "Paragenesis of complex massive sulfide ores from the Tyrrhenian Sea" (PDF). Mitteilungen der Österreichischen Geologischen Gesellschaft. 84: 265–300.

- Würtz, Maurizio (2015). Rovere, Marzia; Würtz, Maurizio (eds.). Atlas of the Mediterranean Seamounts and Seamount-like Structures. Gland. ISBN 978-2-8317-1750-0.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link