Palladium

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Palladium | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /pəˈleɪdiəm/ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | silvery white | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Pd) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Palladium in the periodic table | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 358 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 25.98 J/(mol·K) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Discovery and first isolation | William Hyde Wollaston (1802) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Isotopes of palladium | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Palladium is a

More than half the supply of palladium and its congener platinum is used in catalytic converters, which convert as much as 90% of the harmful gases in automobile exhaust (hydrocarbons, carbon monoxide, and nitrogen dioxide) into nontoxic substances (nitrogen, carbon dioxide and water vapor). Palladium is also used in electronics, dentistry, medicine, hydrogen purification, chemical applications, groundwater treatment, and jewelry. Palladium is a key component of fuel cells, in which hydrogen and oxygen react to produce electricity, heat, and water.

Characteristics

Palladium belongs to

| Z | Element | No. of electrons/shell |

|---|---|---|

| 28 | nickel | 2, 8, 16, 2 (or 2, 8, 17, 1) |

| 46 | palladium | 2, 8, 18, 18, 0 |

| 78 | platinum | 2, 8, 18, 32, 17, 1 |

| 110 | darmstadtium | 2, 8, 18, 32, 32, 16, 2 (predicted) |

This 5s0 configuration, unique in period 5, makes palladium the heaviest element having only one incomplete electron shell, with all shells above it empty.

Palladium has the appearance of a soft silver-white metal that resembles platinum. It is the least dense and has the lowest

Palladium does not react with

Palladium films with defects produced by alpha particle bombardment at low temperature exhibit superconductivity having Tc = 3.2 K.[9]

Isotopes

Naturally occurring palladium is composed of seven

For isotopes with atomic mass unit values less than that of the most abundant stable isotope, 106Pd, the primary

Compounds

Palladium compounds exist primarily in the 0 and +2 oxidation state. Other less common states are also recognized. Generally the compounds of palladium are more similar to those of platinum than those of any other element.

-

Structure of α-PdCl2

-

Structure of β-PdCl2

Palladium(II)

Palladium(II) chloride is the principal starting material for other palladium compounds. It arises by the reaction of palladium with chlorine. It is used to prepare heterogeneous palladium catalysts such as palladium on barium sulfate, palladium on carbon, and palladium chloride on carbon.[15] Solutions of PdCl2 in nitric acid react with acetic acid to give palladium(II) acetate, also a versatile reagent. PdCl2 reacts with ligands (L) to give square planar complexes of the type PdCl2L2. One example of such complexes is the benzonitrile derivative PdCl2(PhCN)2.[16][17]

- PdCl2 + 2 L → PdCl2L2 (L = , etc)

The complex

Palladium(0)

Palladium forms a range of zerovalent complexes with the formula PdL4, PdL3 and PdL2. For example, reduction of a mixture of PdCl2(PPh3)2 and PPh3 gives tetrakis(triphenylphosphine)palladium(0):[19]

- 2 PdCl2(PPh3)2 + 4 PPh3 + 5 N2H4 → 2 Pd(PPh3)4 + N2 + 4 N2H5+Cl−

Another major palladium(0) complex, tris(dibenzylideneacetone)dipalladium(0) (Pd2(dba)3), is prepared by reducing sodium tetrachloropalladate in the presence of dibenzylideneacetone.[20]

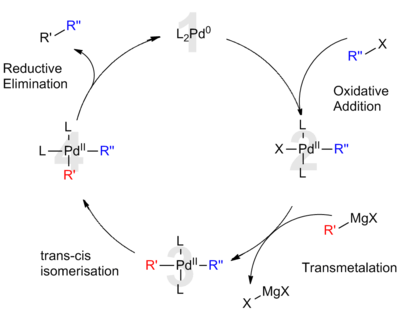

Palladium(0), as well as palladium(II), are catalysts in

Other oxidation states

Although Pd(IV) compounds are comparatively rare, one example is

Mixed valence palladium complexes exist, e.g. Pd4(CO)4(OAc)4Pd(acac)2 forms an infinite Pd chain structure, with alternatively interconnected Pd4(CO)4(OAc)4 and Pd(acac)2 units.[27]

When alloyed with a more

Occurrence

As overall mine production of palladium reached 210,000 kilograms in 2022, Russia was the top producer with 88,000 kilograms, followed by South Africa, Canada, the U.S., and Zimbabwe.[30] Russia's company Norilsk Nickel ranks first among the largest palladium producers globally, accounting for 39% of the world's production.[31]

Palladium can be found as a free metal alloyed with gold and other platinum-group metals in placer deposits of the Ural Mountains, Australia, Ethiopia, North and South America. For the production of palladium, these deposits play only a minor role. The most important commercial sources are nickel-copper deposits found in the Sudbury Basin, Ontario, and the Norilsk–Talnakh deposits in Siberia. The other large deposit is the Merensky Reef platinum group metals deposit within the Bushveld Igneous Complex South Africa. The Stillwater igneous complex of Montana and the Roby zone ore body of the Lac des Îles igneous complex of Ontario are the two other sources of palladium in Canada and the United States.[32][33] Palladium is found in the rare minerals cooperite[34] and polarite.[35] Many more Pd minerals are known, but all of them are very rare.[36]

Palladium is also produced in

Pd, a slightly radioactive long-lived fission product. Depending on end use, the radioactivity contributed by the 107

Pd might make the recovered palladium unusable without a costly step of isotope separation

Applications

The largest use of palladium today is in catalytic converters.

Catalysis

When it is finely divided, as with

- Heck reaction

- Suzuki coupling

- Tsuji-Trost reactions

- Wacker process

- Negishi reaction

- Stille coupling

- Sonogashira coupling

When dispersed on conductive materials, palladium is an excellent electrocatalyst for oxidation of primary alcohols in alkaline media.[45] Palladium is also a versatile metal for homogeneous catalysis, used in combination with a broad variety of ligands for highly selective chemical transformations.

In 2010 the

Palladium catalysis is primarily employed in organic chemistry and industrial applications, although its use is growing as a tool for

Electronics

The primary application of palladium in electronics is in

Technology

Hydrogen easily diffuses through heated palladium,[8] and membrane reactors with Pd membranes are used in the production of high purity hydrogen.[52] Palladium is used in palladium-hydrogen electrodes in electrochemical studies. Palladium(II) chloride readily catalyzes carbon monoxide gas to carbon dioxide and is useful in carbon monoxide detectors.[53]

Hydrogen storage

Palladium readily

Palladium is used for purification of hydrogen on a laboratory[58]: 183–217 but not industrial scale.[59]

Dentistry

Palladium is used in small amounts (about 0.5%) in some alloys of

Jewelry

Palladium has been used as a precious metal in jewelry since 1939 as an alternative to platinum in the alloys called "white gold", where the naturally white color of palladium does not require rhodium plating. Palladium, being much less dense than platinum, is similar to gold in that it can be beaten into leaf as thin as 100 nm (1⁄250,000 in).[8] Unlike platinum, palladium may discolor at temperatures above 400 °C (752 °F)[62] due to oxidation, making it more brittle and thus less suitable for use in jewelry; to prevent this, palladium intended for jewelry is heated under controlled conditions.[63]

Prior to 2004, the principal use of palladium in jewelry was the manufacture of white gold. Palladium is one of the three most popular alloying metals in white gold (nickel and silver can also be used).[38] Palladium-gold is more expensive than nickel-gold, but seldom causes allergic reactions (though certain cross-allergies with nickel may occur).[64]

When platinum became a strategic resource during World War II, many jewelry bands were made out of palladium. Palladium was little used in jewelry because of the technical difficulty of

In January 2010, hallmarks for palladium were introduced by assay offices in the United Kingdom, and hallmarking became mandatory for all jewelry advertising pure or alloyed palladium. Articles can be marked as 500, 950, or 999 parts of palladium per thousand of the alloy.

Fountain pen nibs made from gold are sometimes plated with palladium when a silver (rather than gold) appearance is desired. Sheaffer has used palladium plating for decades, either as an accent on otherwise gold nibs or covering the gold completely.

Palladium is also used by the luxury brand Hermès as one of the metals plating the hardware on their handbags, most famous of which being Birkin.

Photography

In the

Effects on health

Toxicity

| Hazards | |

|---|---|

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Warning | |

| H317 | |

| P261, P273, P280, P302+P352, P321, P333+P313, P363, P501[71] | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

Palladium is a metal with low toxicity as conventionally measured (e.g.

Precautions

Like other

Some palladium is emitted with the exhaust gases of cars with

The

History

William Hyde Wollaston noted the

It was named by Wollaston in 1802 after the asteroid

Most palladium is used for

World demand for palladium increased from 100 tons in 1990 to nearly 300 tons in 2000. The global production of palladium from mines was 222 tonnes in 2006 according to the United States Geological Survey.[32] Many were concerned about a steady supply of palladium in the wake of Russia's annexation of Crimea, partly as sanctions could hamper Russian palladium exports; any restrictions on Russian palladium exports could have exacerbated what was already expected to be a large palladium deficit in 2014.[87] Those concerns pushed palladium prices to their highest level since 2001.[88] In September 2014 they soared above the $900 per ounce mark. In 2016 however palladium cost around $614 per ounce as Russia managed to maintain stable supplies.[89] In January 2019 palladium futures climbed past $1,344 per ounce for the first time on record, mainly due to the strong demand from the automotive industry.[90] Palladium reached $2,024.64 per troy ounce ($65.094/g) on 6 January 2020, passing $2,000 per troy ounce the first time.[91] The price rose above $3,000 per troy ounce in May 2021 and March 2022.[92]

Palladium as investment

Global palladium sales were 8.84 million troy ounces (275 t) in 2017,[93] of which 86% was used in the manufacturing of automotive catalytic converters, followed by industrial, jewelry, and investment usages.[94] More than 75% of global platinum and 40% of palladium are mined in South Africa. Russia's mining company, Norilsk Nickel, produces another 44% of palladium, with US and Canada-based mines producing most of the rest.

The price for palladium reached an all-time high of $2,981.40 per ounce on May 3, 2021,

During the Russo-Ukrainian War in March 2022, prices for palladium increased 13%, since the first of March. Russia is the primary supplier to Europe and the country supplies 37% of the global production.[97]

Palladium producers

Exchange-traded products

WisdomTree Physical Palladium (LSE: PHPD) is backed by allocated palladium bullion and was the world's first palladium ETF. It is listed on the London Stock Exchange as PHPD,[98] Xetra Trading System, Euronext and Milan. ETFS Physical Palladium Shares (NYSE: PALL) is an ETF traded on the New York Stock Exchange.

Bullion coins and bars

A traditional way of investing in palladium is buying bullion coins and bars made of palladium. Available palladium coins include the

See also

- 2000s commodities boom

- 2020s commodities boom

- Bullion

- Bullion coin

- Inflation hedge

- Pseudo palladium

- Rare materials as an investment:

References

- ^ "Standard Atomic Weights: Palladium". CIAAW. 1979.

- ISSN 1365-3075.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-62708-155-9.

- PMID 17470819.

- ISBN 0-8493-0486-5.

- ISBN 0-8493-0464-4.

- .

- ^ ISBN 978-0-8493-0485-9.

- ^ B. Strizker, Phys. Rev. Lett., 42, 1769 (1979).

- ^ "Atomic Weights and Isotopic Compositions for Palladium (NIST)". NIST. 23 August 2009. Retrieved 12 November 2009.

- ^

- S2CID 120355895.

- ^ "Mexico's Meteorites" (PDF). mexicogemstones.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 May 2006.

- .

- ^ Mozingo, Ralph (1955). "Palladium Catalysts". Organic Syntheses; Collected Volumes, vol. 3, p. 685.

- ISBN 978-0-470-13259-3.

- S2CID 95529734.

- ^ Miyaura, Norio & Suzuki, Akira (1993). "Palladium-catalyzed reaction of 1-alkenylboronates with vinylic halides: (1Z,3E)-1-Phenyl-1,3-octadiene". Organic Syntheses; Collected Volumes, vol. 8, p. 532.

- )

- .

- ISBN 978-0-470-25762-3.

- PMID 21461129.

- S2CID 45249108.

- S2CID 94579227.

- PMID 19750645.

- PMID 19750644.

- PMID 25319757.

- PMID 33628119.

- S2CID 98580013.

- doi:10.3133/mcs2023.

- ^ ""Norilsk Nickel" Group announces preliminary consolidated production results for 4 th quarter and full 2016, and production outl". Nornickel. Archived from the original on 29 June 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- ^ a b "Platinum-Group Metals" (PDF). Mineral Commodity Summaries. United States Geological Survey. January 2007.

- ^ "Platinum-Group Metals" (PDF). Mineral Yearbook 2007. United States Geological Survey. January 2007.

- S2CID 53128786.

- .

- ^ "Mindat.org - Mines, Minerals and More". www.mindat.org.

- ^ Kolarik, Zdenek; Renard, Edouard V. (2003). "Recovery of Value Fission Platinoids from Spent Nuclear Fuel. Part I PART I: General Considerations and Basic Chemistry" (PDF). Platinum Metals Review. 47 (2): 74–87.

- ^ a b c d "Palladium". United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. Archived from the original on 6 December 2006. Retrieved 5 February 2007.

- ^ Rushforth, Roy (2004). "Palladium in Restorative Dentistry: Superior Physical Properties make Palladium an Ideal Dental Metal". Platinum Metals Review. 48 (1). Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ISBN 978-0-313-33507-5.

- ISBN 978-0-19-510502-5.

- ISBN 978-0-471-73203-7.

- .

- ISBN 978-0-495-38857-9.

- ISBN 978-0-470-85032-9.

- .

- PMID 28699627.

- ^ Zogbi, Dennis (3 February 2003). "Shifting Supply and Demand for Palladium in MLCCs". TTI, Inc.

- ISBN 978-0-07-041401-3.

- ISBN 978-0-07-026698-8.

- ^ Jollie, David (2007). "Platinum 2007" (PDF). Johnson Matthey. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2008.

- .

- PMID 13252031.

- S2CID 95343702.

- ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- PMID 15008624.

- ISBN 0-486-60456-X. p. 200

- )

- ISBN 978-3-527-30385-4.

- PMID 12628436.

- ISBN 978-0-323-47821-2, retrieved 11 February 2023

- ISBN 978-0-8031-0459-4.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link - ^ Mann, Mark B. (2007). "950 Palladium: Manufacturing Methods".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - S2CID 20927683.

- ^ Battaini, Paolo (2006). "The Working Properties for Jewelry Fabrication Using New Hard 950 Palladium Alloys". SANTA FE SYMPOSIUM PAPERS.

- ^ Holmes, E. (13 February 2007). "Palladium, Platinum's Cheaper Sister, Makes a Bid for Love". The Wall Street Journal (Eastern edition). pp. B.1.

- ^ "Platinum-Group Metals" (PDF). Mineral Yearbook 2009. United States Geological Survey. January 2007.

- ^ "Platinum-Group Metals" (PDF). Mineral Yearbook 2006. United States Geological Survey. January 2007.

- ^ "Johnson Matthey Base Prices". 2019. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- .

- ^ Sigma-Aldrich Co., SDS Palladium.

- ISBN 978-0-19-960563-7.

- ^ PMID 12455264.

- ISBN 978-3-540-29219-7.

- PMID 8736443.

- S2CID 43020912.

- S2CID 41325428.

- ^ .

- ^ a b Griffith, W. P. (2003). "Rhodium and Palladium – Events Surrounding Its Discovery". Platinum Metals Review. 47 (4): 175–183. Archived from the original on 19 April 2013. Retrieved 24 March 2005.

- .

- .

- S2CID 94929244.

- ^ Williamson, Alan. "Russian PGM Stocks" (PDF). The LBMA Precious Metals Conference 2003. The London Bullion Market Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- ^ "Historical Palladium Prices and Price Chart". InvestmentMine. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- ^ "Ford fears first loss in a decade". BBC News. 16 January 2002. Retrieved 19 September 2008.

- ^ Nat Rudarakanchana (27 March 2014). "Palladium Fund Launches in South Africa, As Russian Supply Fears Warm Prices". International Business Times.

- ^ Rosenfeld, Everett (20 August 2014). "The other commodity that's leaping on Ukraine war". CNBC. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- ^ "Palladium Rally Is About More Than Just Autos". Bloomberg.com. 30 August 2017. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- ^ "Don't Expect Palladium Prices To Plunge | OilPrice.com". OilPrice.com. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- ^ "Gold soars as Middle East tensions brew perfect storm | Reuters". Reuters. 6 January 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2020.

- ^ Patel, Brijesh (4 March 2022). "Palladium tops $3,000/oz as supply fears grow, gold jumps over 1%". Reuters.

- ^ "Total palladium supply worldwide 2017 | Statistic". Statista. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- ^ "Global palladium demand distribution by application 2016 | Statistic". Statista. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- ^ "Historical Palladium Charts and Data - London Fix".

- ^ "CPI Inflation Calculator". data.bls.gov. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- ^ Staff, Writer (OilPrice.com) (10 March 2022). "Palladium Prices Are Soaring As Russian Sanctions Sting". Yahoo! Finance. OilPrice.com. Retrieved 13 March 2022.

- ^ "ETFS METAL PAL ETP price (PHPD)". London Stock Exchange.

- ^ "Size of the Palladium Market | Sunshine Profits". www.sunshineprofits.com. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

External links

- Palladium at The Periodic Table of Videos(University of Nottingham)

- Current and Historical Palladium Price

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 20 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 636–637.