Paranthodon

| Paranthodon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reconstruction of the skull; grey material is unknown. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Clade: | †Thyreophora |

| Clade: | †Stegosauria |

| Family: | †Stegosauridae |

| Genus: | †Paranthodon Nopcsa, 1929[2]

|

| Species: | †P. africanus

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Paranthodon africanus | |

| Synonyms[4] | |

Paranthodon (

In identifying the remains as those of Palaeoscincus, Broom initially classified Paranthodon as an

History of discovery

In 1845, amateur geologists

In 1909,

Material

The holotype of Paranthodon, BMNH 47338, was found in a layer of the Kirkwood Formation that has been dated between the Berriasian and early Valanginian ages. It consists of the back of the snout, containing the maxilla with teeth, the posterior caudodorsal ramus of the premaxilla, part of the nasals, and some isolated teeth probably from the lower jaw. One additional specimen was assigned to it based on the dentition, BMNH (now NHMUK) R4992, including only isolated teeth sharing the same morphology as those from the holotype.[10] Some bones that were unidentified by Galton & Coombs (1981) were described as a fragment of a vertebra in 2018 by Raven & Maidment.[4] The teeth do not bear any autapomorphies of Paranthodon, and were referred to an indeterminate stegosaurid in 2008.[13] The teeth were identified in 2018 as also lacking any distinct stegosaurian features, and were thus designated as Thyreophora indeterminate.[4]

The Mugher Mudstone of Ethiopia was screened in the 1990s by the University of California Museum of Paleontology, and in it were discovered multiple dinosaur teeth, pertaining to many groups of taxa. The locality has been described as "the largest and most complete record of dinosaur fossils from a Late Jurassic African locality outside of Tendaguru". Two of the partial teeth discovered were referred to Paranthodon by Lee Hall and Mark Goodwin in 2011. The reasons for the referral to Paranthodon were not discussed.[14]

Description

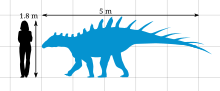

Paranthodon was a small relative of larger stegosaurids such as Stegosaurus.

The premaxilla of Paranthodon is incomplete, but the anterior process is sinuous and curves

Thirteen teeth are preserved in Paranthodon, but as they extend to the back of the maxilla there were possibly more in life. The teeth are symmetrical as in stegosaurs except Chungkingosaurus. Along the base of the

As only two fragments of a vertebra are known, few anatomical details can be observed. The right

Classification

Currently, Paranthodon is classified as a stegosaur related to Stegosaurus, Tuojiangosaurus, and Loricatosaurus. Initially, when Broom assigned the name Palaeoscincus africanus to the Paranthodon fossils, he classified them as an ankylosaurian. This classification was later changed by Nopcsa, who found that Paranthodon best resembled a stegosaurid (before the group was truly defined[18]). Coombs (1978) did not follow Nopcsa's classification, keeping Paranthodon as an ankylosaurian, like Broom, although he only classified it as Ankylosauria incertae sedis.[19] A subsequent review by Galton and Coombs in 1981 instead confirmed Nopcsa's interpretation, redescribing Paranthodon as a stegosaurid from the Lower Cretaceous.[10][16] Paranthodon was distinguished from other stegosaurs by a long, wide, posterior process of the premaxilla, teeth in the maxilla with a very large cingulum, and large ridges on the tooth crowns.[11] Not all of these features were considered valid in a 2008 review of Stegosauria, with the only autapomorphy found being the possession of a partial second bony palate on the maxilla.[13]

Multiple phylogenetic analyses have placed Paranthodon in Stegosauria, and often in Stegosauridae. A 2010 analysis including nearly all species of stegosaurians found that Paranthodon was outside Stegosauridae, and in a polytomy with Tuojiangosaurus, Huayangosaurus, Chungkingosaurus, Jiangjunosaurus, and Gigantspinosaurus. When the latter two genera were removed, Paranthodon grouped with Tuojiangosaurus just outside Stegosauridae, and Huayangosaurus grouped with Chungkingosaurus in Huayangosauridae.[20] An elaboration upon this analysis was published in 2017 by Susannah Maidment and Thomas Raven, and it resolved relationships within Stegosauria much more. All taxa were remained included, and Paranthodon grouped with Tuojiangosaurus, Huayangosaurus and Chunkingosaurus as the most basal true stegosaurians. The position of Alcovasaurus was uncertain, and further work could change the result. Below is the analysis.[21]

| Thyreophora |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Other analyses have found Paranthodon closely related to Tuojiangosaurus, Loricatosaurus, and Kentrosaurus within

Paleoecology

The Kirkwood Formation is in South Africa, and many fossils of different

If the referral of teeth from Ethiopia to Paranthodon is correct, then the taxon's geographic range is extended significantly. The Mugher locality is approximately 151 million years old, about 14 million older than has previously been suggested for Paranthodon, as well as across both southern and eastern Africa. The fauna in the Mugher locality differ from elsewhere of the same time and place in Africa. While the Tendaguru has abundant stegosaurs, sauropods,

References

![]() This article was submitted to WikiJournal of Science for external academic peer review in 2018 (reviewer reports). The updated content was reintegrated into the Wikipedia page under a CC-BY-SA-3.0 license (2019). The version of record as reviewed is:

Iain Reid; et al. (2020). "Paranthodon" (PDF). WikiJournal of Science. 3 (1): 1.

This article was submitted to WikiJournal of Science for external academic peer review in 2018 (reviewer reports). The updated content was reintegrated into the Wikipedia page under a CC-BY-SA-3.0 license (2019). The version of record as reviewed is:

Iain Reid; et al. (2020). "Paranthodon" (PDF). WikiJournal of Science. 3 (1): 1. {{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link

- ^ .

- ^ a b c d Nopsca, F. (1929). "Dinosaurierreste aus Siebenburgen V. Geologica Hungarica. Series Palaeontologica". Fasciculus. 4 (1): 13.

- ^ a b c Owen, R. (1876). "Descriptive and illustrated catalogue of the fossil Reptilia of South Africa in the collection of the British Museum". Order of the Trustees: 14–15.

- ^ PMID 29576986.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-375-92419-4.

- ^ a b Atherstone, W.G. (1857). "Geology of Uitenhage". The Eastern Province Monthly Magazine. 1 (10): 518–532.

- ^ from the original on 31 January 2019. Retrieved 31 January 2019.

- .

- ^ Atherstone, W.G. (1871). "From Graham's Town to the Gouph". Selected articles from the Cape Monthly Magazine (New Series 1870–76). Cape Town: Van Riebeeck Society.

- ^ .

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7864-7222-2.

- ^ Olshevsky, G. (1978). "The Archosaurian Taxa (excluding the Crocodylia)". Mesozoic Meanderings (1): 1–50.

- ^ S2CID 85673680.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 14 December 2017. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- ^ Holtz, T.R. Jr. (2014). "Supplementary Information to Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages". University of Maryland. Archived from the original on 2 November 2014. Retrieved 5 September 2014.

- ^ ISSN 0077-7749.

- ISBN 978-0-253-33964-5.

- ^ Sereno, P.C. (2005). "Stegosauridae". TaxonSearch: Database for Suprageneric Taxa & Phylogenetic Definitions. Archived from the original on 1 July 2015. Retrieved 2 October 2014.

- ^ Coombs, W.P. Jr. (1978). "The Families of the Ornithischian Dinosaur Order Ankylosauria" (PDF). Palaeontology. 21 (1): 143–170. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2015. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- ^ S2CID 84415016.

- (PDF) from the original on 19 August 2018. Retrieved 6 August 2018.

- ISBN 978-0-253-00849-7.

- ^ S2CID 131280290.

- ISSN 0213-6937.

- ^ hdl:10044/1/27470.

- S2CID 129160518.

- ISBN 978-0-12-226810-6.

See also