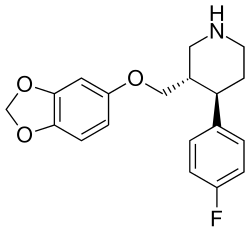

Paroxetine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Paxil, Seroxat, Loxamine |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a698032 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | Oral (By mouth) |

| Drug class | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Identifiers | |

| |

JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Paroxetine, sold under the brand names Paxil and Seroxat among others, is an

Common side effects include drowsiness, dry mouth, loss of appetite, sweating,

Paroxetine was approved for medical use in the United States in 1992 and initially sold by

Medical uses

Paroxetine is primarily used to treat

Depression

A variety of meta-analyses have been conducted to evaluate the efficacy of paroxetine in depression. They have variously concluded that paroxetine is superior or equivalent to placebo and that it is equivalent to other antidepressants.[26][27][28] Despite this, there was no clear evidence that paroxetine was better or worse compared with other antidepressants at increasing response to treatment at any point in time.[29]

Anxiety disorders

Paroxetine was the first antidepressant approved in the United States for the treatment of panic disorder.[30][page needed] Several studies have concluded that paroxetine is superior to placebo in the treatment of panic disorder.[28][31]

Paroxetine has demonstrated efficacy for the treatment of social anxiety disorder in adults and children.

Paroxetine is used in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder.[36] Comparative efficacy of paroxetine is equivalent to that of clomipramine and venlafaxine.[37][38] Paroxetine is also effective for children with obsessive-compulsive disorder.[39]

Paroxetine is approved for treatment of PTSD in the United States, Japan, and Europe.[40][41][42] In the United States, it is approved for short-term use.[41]

Paroxetine is also FDA-approved for generalized anxiety disorder.[43]

Menopausal hot flashes

In 2013, low-dose paroxetine was approved in the US for the treatment of moderate-to-severe

Fibromyalgia

Studies have also shown paroxetine "appears to be well-tolerated and improve the overall symptomatology in patients with fibromyalgia", but is less robust in helping with the pain involved.[45][46]

Adverse effects

Common side effects include drowsiness, dry mouth, loss of appetite, sweating, insomnia, and sexual dysfunction.[7] Serious side effects may include suicide in those under the age of 25, serotonin syndrome, and mania.[7] While the rate of side effects appears similar compared to other SSRIs and SNRIs, antidepressant discontinuation syndromes may occur more often.[9][10] Use in pregnancy is not recommended, while use during breastfeeding is relatively safe.[11]

Paroxetine shares many of the common adverse effects of SSRIs, including (with the corresponding rates seen in people treated with placebo in parentheses):

- nausea 26% (9%)

- diarrhea 12% (8%)

- constipation 14% (9%)

- dry mouth 18% (12%)

- somnolence 23% (9%)

- insomnia 13% (6%)

- headache 18% (17%)

- hypomania 1% (0.3%)

- blurred vision 4% (1%)

- loss of appetite 6% (2%)

- nervousness 5% (3%)

- paraesthesia4% (2%)

- dizziness 13% (6%)

- asthenia (weakness; 15% (6%))

- tremor 8% (2%)

- sweating 11% (2%)

- sexual dysfunction (≥10% incidence).[6]

Most of these adverse effects are transient and go away with continued treatment. Central and peripheral 5-HT3 receptor stimulation is believed to result in the gastrointestinal effects observed with SSRI treatment.[47] Compared to other SSRIs, it has a lower incidence of diarrhea, but a higher incidence of anticholinergic effects (e.g., dry mouth, constipation, blurred vision, etc.), sedation/somnolence/drowsiness, sexual side effects, and weight gain.[48]

Due to reports of adverse withdrawal reactions upon terminating treatment, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use at the European Medicines Agency recommends gradually reducing over several weeks or months if the decision to withdraw is made.[49] See also Discontinuation syndrome (withdrawal).

Mania or hypomania may occur in 1% of patients with depression and up to 12% of patients with bipolar disorder.[50] This side effect can occur in individuals with no history of mania, but it may be more likely to occur in those with bipolar disorder or with a family history of mania.[51]

Suicide

Like other antidepressants, paroxetine may increase the risk of suicidal thinking and behaviour in people under the age of 25.[52][53] The FDA conducted a statistical analysis of paroxetine clinical trials in children and adolescents in 2004 and found an increase in suicidality and ideation as compared to placebo, which was observed in trials for both depression and anxiety disorders.[54] In 2015 a paper published in The BMJ that reanalysed the original case notes argued that in Study 329,[55] assessing paroxetine and imipramine against placebo in adolescents with depression, the incidence of suicidal behavior had been under-reported and the efficacy exaggerated for paroxetine.[56][57][58][59][60]

Sexual dysfunction

Sexual dysfunction, including loss of libido, anorgasmia, lack of vaginal lubrication, and erectile dysfunction, is one of the most commonly encountered adverse effects of treatment with paroxetine and other SSRIs. While early clinical trials suggested a relatively low rate of sexual dysfunction, more recent studies in which the investigator actively inquires about sexual problems suggest that the incidence is higher than 70%.[61] Symptoms of sexual dysfunction have been reported to persist after discontinuing SSRIs, although this is thought to be occasional.[62][63][64]

Pregnancy

Antidepressant exposure (including paroxetine) is associated with shorter duration of pregnancy (by three days), increased risk of preterm delivery (by 55%), lower birth weight (by 75 g or 2.6 oz), and lower

Babies born to women who used paroxetine during the first trimester have an increased risk of cardiovascular malformations, primarily ventricular and atrial septal defects. Unless the benefits of paroxetine justify continuing treatment, consideration should be given to stopping or switching to another antidepressant.[69] Paroxetine use during pregnancy is associated with about 1.5– to 1.7-fold increase in congenital birth defects, in particular, heart defects, cleft lip and palate, clubbed feet, or any birth defects.[70][71][72][73][74]

Discontinuation syndrome

Many psychoactive medications can cause withdrawal symptoms upon discontinuation from administration. Paroxetine has among the highest incidence rates and severity of withdrawal syndrome of any medication of its class.[75] Common withdrawal symptoms for paroxetine include nausea, dizziness, lightheadedness and vertigo; insomnia, nightmares and vivid dreams; feelings of electricity in the body, as well as rebound depression and anxiety. Liquid formulation of paroxetine is available and allows a very gradual decrease of the dose, which may prevent discontinuation syndrome. Another recommendation is to temporarily switch to fluoxetine, which has a longer half-life and thus decreases the severity of discontinuation syndrome.[76][77][78]

In 2002, the U.S. FDA published a warning regarding "severe" discontinuation symptoms among those terminating paroxetine treatment, including paraesthesia, nightmares, and dizziness. The agency also warned of case reports describing agitation, sweating, and nausea. In connection with a Glaxo spokesperson's statement that withdrawal reactions occur only in 0.2% of patients and are "mild and short-lived", the

Paroxetine prescribing information posted at GlaxoSmithKline has been updated related to the occurrence of a discontinuation syndrome, including serious discontinuation symptoms.[69]

Overdose

Acute overdosage is often manifested by

Interactions

Interactions with other drugs acting on the serotonin system or impairing the metabolism of serotonin may increase the risk of serotonin syndrome or neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS)-like reaction. Such reactions have been observed with SNRIs and SSRIs alone, but particularly with concurrent use of triptans, MAO inhibitors, antipsychotics, or other dopamine antagonists.

The prescribing information states that paroxetine should "not be used in combination with an MAOI (including linezolid, an antibiotic which is a reversible non-selective MAOI), or within 14 days of discontinuing treatment with an MAOI", and should not be used in combination with pimozide, thioridazine, tryptophan, or warfarin.[69]

Paroxetine interacts with the following cytochrome P450 enzymes:[48][83]

- CYP2B6 (strong) inhibitor.

- CYP3A4 (weak) inhibitor.

- CYP1A2 (weak) inhibitor.

- CYP2C9 (weak) inhibitor.

- CYP2C19 (weak) inhibitor.

Paroxetine has been shown to be an inhibitor of G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 (GRK2).[84][85]

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Paroxetine is the most potent and one of the most specific selective serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).[87] It also binds to the allosteric site of the serotonin transporter, similarly to escitalopram, though less potently so.[88] Paroxetine also inhibits the reuptake of norepinephrine to a lesser extent (<50 nmol/L).[89] Based on evidence from four weeks of administration in rats, the equivalent of 20 mg paroxetine taken once daily occupies approximately 88% of serotonin transporters in the prefrontal cortex.[83]

| Receptor | Ki (nM) |

|---|---|

| SERT | 0.07 – 0.2 |

| NET | 40 – 85 |

| DAT | 490 |

| D2 | 7,700 |

| 5-HT1A | 21,200 |

| 5-HT2A | 6,300 |

| 5-HT2C | 9,000 |

| α1 | 1,000 – 2,700 |

| α2 | 3,900 |

| M1 | 72 |

| H1 | 13,700 – 23,700 |

Pharmacokinetics

Paroxetine is well-absorbed following oral administration.[83] It has an absolute bioavailability of about 50%, with evidence of a saturable first pass effect.[93] When taken orally, it achieves maximum concentration in about 6–10 hours[83] and reaches steady-state in 7–14 days.[93] Paroxetine exhibits significant interindividual variations in volume of distribution and clearance.[93] Less than 2% of an oral dose is excreted in urine unchanged.[93]

Paroxetine is a mechanism-based inhibitor of CYP2D6.[86][94]

Society and culture

Paroxetine was approved for medical use in the United States in 1992 and initially sold by

GlaxoSmithKline has paid substantial fines, paid settlements in

Marketing

In early 2004, GSK agreed to settle charges of consumer fraud for $2.5 million.

The United States Department of Justice fined GlaxoSmithKline $3 billion in 2012, for withholding data, unlawfully promoting use in those under 18, and preparing an article that misleadingly reported the effects of paroxetine in adolescents with depression following its clinical trial study 329.[18][19][20]

In February 2016, the UK

GSK marketed paroxetine through television advertisements throughout the late 1990s and early 2000s. Commercials also aired for the CR version of the drug beginning in 2003.[104]

Economics

In 2007, paroxetine was ranked 94th on the

Brand names

Brand names include Aropax, Paretin, Brisdelle, Deroxat, Paxil,[108][109] Pexeva, Paxtine, Paxetin, Paroxat, Paraxyl,[110] Sereupin, Daparox and Seroxat.

Research

Several studies have suggested that paroxetine can be used in the treatment of premature ejaculation. In particular, intravaginal ejaculation latency time (IELT) was found to increase with 6- to 13-fold, which was somewhat longer than the delay achieved by the treatment with other SSRIs (fluvoxamine, fluoxetine, sertraline, and citalopram).[111][112][113] However, paroxetine taken acutely ("on demand") 3–10 hours before coitus resulted only in a "clinically irrelevant and sexually unsatisfactory" 1.5-fold delay of ejaculation and was inferior to clomipramine, which induced a fourfold delay.[113]

There is also evidence that paroxetine may be effective in the treatment of

Benefits of paroxetine prescription for diabetic neuropathy[116] or chronic tension headache[117] are uncertain.

Although the evidence is conflicting, paroxetine may be effective for the treatment of dysthymia, a chronic disorder involving depressive symptoms for most days of the year.[118]

There is evidence to support that paroxetine selectively binds to and inhibits G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 (GRK2) in mice with heart failure. Since GRK2 regulates the activity of the beta adrenergic receptor, which becomes desensitized in cases of heart failure, paroxetine (or a paroxetine derivative) could be used as a heart failure treatment in the future.[84][85][119]

Paroxetine has been identified as a potential disease-modifying osteoarthritis drug.[120]

Other organisms

Paroxetine is a common finding in waste water.[121] It is highly toxic to the alga Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata (syn. Raphidocelis subcapitata).[121]

It also is toxic to the soil nematode Caenorhabditis elegans.[122]

Alberca et al., 2016 finds paroxetine acts as a

Alberca et al., 2016 finds a

References

- FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ Anvisa (31 March 2023). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 4 April 2023). Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 3 August 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Sandoz Pty Ltd (18 January 2012). "Product Information Paroxetine Sandoz 20Mg Film-Coated Tablets" (PDF). Therapeutic Goods Administration. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Mylan Institutional Inc. (January 2012). "Paroxetine (paroxetine hydrochloride hemihydrate) tablet, film coated". DailyMed. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 23 October 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Sandoz Limited (21 March 2013). "Paroxetine 20 mg Tablets – Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC)". electronic Medicines Compendium. Datapharm Ltd. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ a b "Paxil, Paxil CR (paroxetine) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Archived from the original on 10 November 2015. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k "Paroxetine Hydrochloride Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ a b Fischer A (28 June 2013). "FDA approves the first non-hormonal treatment for hot flashes associated with menopause" (Press release). Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017.

- ^ PMID 21286371.

- ^ S2CID 34636522.

- ^ a b "Paroxetine Pregnancy and Breastfeeding Warnings". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 3 December 2018. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ISBN 9781934899816. Archivedfrom the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- hdl:10665/345533. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- ^ ISBN 9780857113382.

- ^ a b "The Top 300 of 2021". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 15 January 2024. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ a b "Paroxetine - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ Grohol JM (15 December 2019). "Top 25 Psychiatric Medications for 2018". psychcentral.com. Archived from the original on 25 October 2020. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- ^ a b c "GlaxoSmithKline to Plead Guilty and Pay $3 Billion to Resolve Fraud Allegations and Failure to Report Safety Data" (Press release). United States Department of Justice, Office of Public Affairs. 2 July 2012. Archived from the original on 9 September 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

The United States alleges that, among other things, GSK participated in preparing, publishing and distributing a misleading medical journal article that misreported that a clinical trial of Paxil demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of depression in patients under age 18, when the study failed to demonstrate efficacy.

- ^ a b c United States ex rel. Greg Thorpe, et al. v. GlaxoSmithKline PLC, and GlaxoSmithKline LLC, pp. 3–19 (D. Mass. 26 October 2011), Text, archived from the original on 19 October 2014.

- ^ a b Thomas K, Schmidt MS (2 July 2012). "Glaxo Agrees to Pay $3 Billion in Fraud Settlement". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 March 2017. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- S2CID 195692589.

- from the original on 14 February 2016. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- ^ "Paroxetine: an antidepressant". nhs.uk. 29 August 2018. Archived from the original on 14 May 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ "Paroxetine 20 mg Tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) - (emc)". medicines.org.uk. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ "Product and Consumer Medicine Information". Therapeutic Goods Administration. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- S2CID 35858125.

- PMID 9988054.

- ^ PMID 25162656.

- PMID 24696195.

- ISBN 978-0-19-516878-5.

- PMID 9433336.

- PMID 9728642.

- from the original on 27 August 2017. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- S2CID 23395959.

- PMID 22436306.

There were no significant differences between the three SSRIs that had been tested in placebo-controlled studies: paroxetine; sertraline; fluvoxamine.

- S2CID 205143838.

- S2CID 19698156.

- S2CID 23260081.

- PMID 19588367.

- PMID 22346334.

- ^ PMID 21798109.

- ^ "Search results detail| Kusurino-Shiori (Drug information Sheet)". rad-ar.or.jp. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- .

- PMID 24806158.

- PMID 17466657.

- .

- ^ ISBN 978-0-07-162442-8.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-60327-434-0.

- ^ "Press release, CHMP meeting on Paroxetine and other SSRIs" (PDF). European Medicines Agency. 9 December 2004. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 24 August 2007.

- ^ "Prescribing Information Paxil (paroxetine hydrochloride) Tablets and Oral Suspension" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 May 2014.

- S2CID 32168369.

- ^ "Medication Guide About Using Antidepressants in Children and Teenagers" (PDF). FDA. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 March 2016.

- ^ "FDA Launches a Multi-Pronged Strategy to Strengthen Safeguards for Children Treated With Antidepressant Medications". Food and Drug Administration. Archived from the original on 18 January 2017.

- ^ Hammad TA (16 August 2004). "Review and evaluation of clinical data: relationship between psychotropic drugs and pediatric suicidality" (PDF). Joint Meeting of the Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee and Pediatric Advisory Committee. 13–14 September 2004. Briefing Information. FDA. p. 30. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 June 2008. Retrieved 27 January 2009.

- S2CID 2125130.

- PMID 26376805.

- .

- S2CID 44921667.

- S2CID 41871189.

- ^ Boseley S (16 September 2015). "Seroxat study under-reported harmful effects on young people, say scientists". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 May 2016. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- PMID 24288712.

- PMID 18173768.

- (PDF) from the original on 5 February 2016. Retrieved 10 January 2016.

- ^ http://pi.lilly.com/us/prozac.pdf Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine Page 14.

- PMID 23446732.

- PMID 16015372.

- PMID 17138801.

- PMID 24313569.

- ^ GlaxoSmithKline. August 2007. Archived from the original(PDF) on 4 September 2011. Retrieved 14 August 2007.

- S2CID 28814479.

- S2CID 37923558.

- S2CID 21279773.

- S2CID 20167648.

- PMID 17697910.

- PMID 25721705.

- S2CID 26897797.

- .

- ^ Healy D. "Dependence on Antidepressants & Halting SSRIs". benzo.org.uk. Archived from the original on 10 May 2013. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- PMID 11823353.

- PMID 10855970.

- ^ R. Baselt,Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp. 1190–1193.

- PMID 19031375.

- ^ PMID 24424469.

- ^ PMID 22882301.

- ^ PMID 28323425.

- ^ .

- S2CID 6037759.

- PMID 16448580.

- PMID 12232544.

- S2CID 11247427.

- ^ Roth BL, Driscol J (12 January 2011). "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Archived from the original on 8 November 2013. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- PMID 24424469.

- ^ S2CID 23769424.

- ^ S2CID 1795852.

- ISBN 9781934899816. Archivedfrom the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- New York Review of Books. Vol. 56, no. 1.

- PMID 14993169.

- ^ "CMA fines pharma companies £45 million". Archived from the original on 13 July 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ^ "GlaxoSmithKline Summary" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 October 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ^ "Generics Summary" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 October 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ^ "Xellia Summary" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 October 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ^ "Merck Summary" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 October 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ^ "Actavis Summary" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 October 2016. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ^ "Paxil CR -- Nametag -- (2003) :30 (USA) | Adland". Archived from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 24 February 2020.

- ^ The paroxetine prescriptions were calculated as a total of prescriptions for Paxil CR and generic paroxetine using data from the charts for generic and brand-name drugs."Top 200 generic drugs by units in 2006. Top 200 brand-name drugs by units". Drug Topics, 5 March 2007. Archived from the original on 21 January 2013. Retrieved 8 April 2007.

- ^ The paroxetine prescriptions were calculated as a total of prescriptions for Paxil CR and generic paroxetine using data from the charts for generic and brand-name drugs."Top 200 generic drugs by units in 2007". Drug Topics. 18 February 2008. Archived from the original on 18 July 2009. Retrieved 23 October 2008.

- ^ "Top 200 brand drugs by units in 2007". Drug Topics, 18 February 2008. Archived from the original on 29 June 2009. Retrieved 23 October 2008.

- PMID 27738376.

- ^ Coleman A (2006). Dictionary of Psychology (Second ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 552.

- ^ Coleman A (2006). Dictionary of Psychology (Second ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 161.

- PMID 9690692.

- S2CID 36888042.

- ^ PMID 15363569.

- PMID 12088161.

- PMID 11997203.

- S2CID 42327989.

- S2CID 13715774.

- PMID 19017592.

- ^ "Common antidepressant may hold key to heart failure reversal". ScienceDaily. Archived from the original on 5 April 2019. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- S2CID 231875553.

- ^ a b

- • Chia MA, Lorenzi AS, Ameh I, Dauda S, Cordeiro-Araújo MK, Agee JT, et al. (May 2021). "Susceptibility of phytoplankton to the increasing presence of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) in the aquatic environment: A review". S2CID 6562531.

- • Chia MA, Lorenzi AS, Ameh I, Dauda S, Cordeiro-Araújo MK, Agee JT, et al. (May 2021). "Susceptibility of phytoplankton to the increasing presence of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) in the aquatic environment: A review".

- ^

- • Mangoni AA, Tuccinardi T, Collina S, Vanden Eynde JJ, Muñoz-Torrero D, Karaman R, et al. (June 2018). "Breakthroughs in Medicinal Chemistry: New Targets and Mechanisms, New Drugs, New Hopes-3". S2CID 205636792.

- • Mangoni AA, Tuccinardi T, Collina S, Vanden Eynde JJ, Muñoz-Torrero D, Karaman R, et al. (June 2018). "Breakthroughs in Medicinal Chemistry: New Targets and Mechanisms, New Drugs, New Hopes-3".

- ^

Ribeiro V, Dias N, Paiva T, Hagström-Bex L, Nitz N, Pratesi R, Hecht M (April 2020). "Current trends in the pharmacological management of Chagas disease". S2CID 209435439. This review cites this study. Alberca LN, Sbaraglini ML, Balcazar D, Fraccaroli L, Carrillo C, Medeiros A, et al. (April 2016). "Discovery of novel polyamine analogs with anti-protozoal activity by computer guided drug repositioning".S2CID 25677082.

- ^ a b c

Andrade-Neto VV, Cunha-Junior EF, Dos Santos Faioes V, Pereira TM, Silva RL, Leon LL, Torres-Santos EC (January 2018). "Leishmaniasis treatment: update of possibilities for drug repurposing". Frontiers in Bioscience. 23 (5). PMID 28930585. This review cites this research. Alberca LN, Sbaraglini ML, Balcazar D, Fraccaroli L, Carrillo C, Medeiros A, et al. (April 2016). "Discovery of novel polyamine analogs with anti-protozoal activity by computer guided drug repositioning". Journal of Computer-Aided Molecular Design. 30 (4).S2CID 25677082.