Peloneustes

| Peloneustes | |

|---|---|

| |

| Skeletal mount, Museum of Paleontology, Tuebingen | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Superorder: | †Sauropterygia |

| Order: | †Plesiosauria |

| Family: | †Pliosauridae |

| Genus: | †Peloneustes Lydekker, 1889 |

| Species: | †P. philarchus

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Peloneustes philarchus Seeley , 1869 | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Peloneustes (meaning 'mud swimmer') is a

With a total length of 3.5–4 metres (11–13 ft), Peloneustes is not a large pliosaurid. It had a large, triangular skull, which occupied about a fifth of its body length. The front of the skull is elongated into a narrow rostrum (snout). The mandibular symphysis, where the front ends of each side of the mandible (lower jaw) fuse, is elongated in Peloneustes, and helped strengthen the jaw. An elevated ridge is located between the tooth rows on the mandibular symphysis. The teeth of Peloneustes are conical and have circular cross-sections, bearing vertical ridges on all sides. The front teeth are larger than the back teeth. With only 19 to 21 cervical (neck) vertebrae, Peloneustes had a short neck for a plesiosaur. The limbs of Peloneustes were modified into flippers, with the back pair larger than the front.

Peloneustes has been interpreted as both a close relative of

History of research

The

Naturalist

The Leeds Collection contained multiple Peloneustes specimens.[10]: 63–70 In 1895, palaeontologist Charles William Andrews described the anatomy of the skull of Peloneustes based on four partial skulls in the Leeds Collection.[11] In 1907, geologist Frédéric Jaccard published a description of two Peloneustes specimens from the Oxford Clay near Peterborough, housed in the Musée Paléontologique de Lausanne, Switzerland. The more complete of the two specimens includes a complete skull preserving both jaws; multiple isolated teeth; 13 cervical (neck), 5 pectoral (shoulder), and 7 caudal (tail) vertebrae; ribs; both scapulae, a coracoid; a partial interclavicale; a complete pelvis save for an ischium; and all four limbs, which were nearly complete. The other specimen preserved 33 vertebrae and some associated ribs. Since the specimen Lydekker described was in some need of restoration, and missing information was filled in with data from other specimens in his publication, Jaccard found it pertinent to publish a description containing photographs of the more complete specimen in Lausanne to better illustrate the anatomy of Peloneustes.[12]

In 1913, naturalist Hermann Linder described multiple specimens of Peloneustes philarchus housed in the Institut für Geowissenschaften,

Andrews later described the

In 1960, palaeontologist

Other assigned species

Many further species have been assigned to Peloneustes throughout its

Another of the species described by Seeley in 1869 was Pliosaurus evansi, based on specimens in the Woodwardian Museum.

Palaeontologist E. Koken described another species of Peloneustes, P. kanzleri, in 1905, from the

In 1998, palaeontologist Frank Robin O'Keefe proposed that a pliosaurid specimen from the Lower Jurassic

Description

Peloneustes is a small-[10]: 34 to medium-sized member of Pliosauridae.[23]: 12 NHMUK R3318, the mounted skeleton in the Natural History Museum in London, is 3.5 metres (11.5 ft) long,[14] while the mounted skeleton in the Institut für Geowissenschaften, University of Tübingen measures 4.05 metres (13.3 ft) in length.[13] Plesiosaurs typically can be described as being of the small-headed, long-necked "plesiosauromorph" morphotype or the large-headed, short-necked "pliosauromorph" morphotype.[24] Peloneustes is of the latter morphotype,[24] with its skull making up a little less than a fifth of the animal's total length.[23]: 13 Peloneustes, like all plesiosaurs, had a short tail, massive torso, and all of its limbs modified into large flippers.[23]: 3

Skull

While the holotype of Peloneustes lacks the rear portion of its cranium, many additional well-preserved specimens, including one that has not been crushed from top to bottom, have been assigned to this genus. These crania vary in size, measuring 60–78.5 centimetres (1.97–2.58 ft) in length. The cranium of Peloneustes is elongated, and slopes upwards towards its back end.

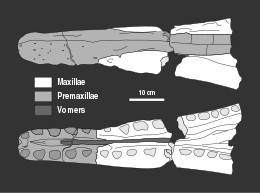

Characteristically, the

Peloneustes is known from many mandibles, some of which are well-preserved. The longest of these measures 87.7 centimetres (2.88 ft). The mandibular symphysis is elongated, making up about a third of the total mandibular length. Behind the symphysis, the two sides of the mandible diverge before gently curving back inwards near the hind end. Each

The teeth of Peloneustes have circular cross sections, as seen in other pliosaurids of its age.

Postcranial skeleton

In 1913, Andrews reported that Peloneustes had 21 to 22 cervical, 2 to 3 pectoral, and around 20

The pectoral vertebrae bear articulations for their respective ribs partially on both their centra and neural arches. Following these vertebrae are the dorsal vertebrae, which are more elongated than the cervical vertebrae and have shorter neural spines. The sacral and caudal vertebrae both have less elongated centra that are wider than tall. Many of the ribs from the hip and the base of the tail bear enlarged outer ends that seem to articulate with each other. Andrews hypothesised in 1913 that this configuration would have stiffened the tail, possibly to support the large hind limbs. The terminal (last) caudal vertebrae sharply decrease in size and would have supported proportionately larger

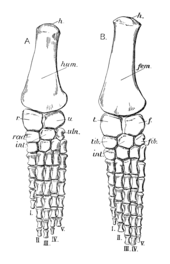

The shoulder girdle of Peloneustes was large, although not as heavily built as in some other plesiosaurs. The coracoids are the largest bones in the shoulder girdle, and are plate-like in form. The shoulder joint is formed by both the

The hind limbs of Peloneustes are longer than its forelimbs, with the femur being longer than the humerus, although the humerus is the more robust of the two elements.

Classification

Seeley initially described Peloneustes as a species of Plesiosaurus, a rather common practice (at the time, the scope of genera was similar to what is currently used for

Within Pliosauridae, the exact phylogenetic position of Peloneustes is uncertain.

The following cladogram follows Ketchum and Benson, 2022.[37]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Palaeobiology

Plesiosaurs were well-adapted to marine life.

Plesiosaurs such as Peloneustes employed a method of swimming known as

Feeding mechanics

In a 2001 dissertation, Noè noted many adaptations in pliosaurid skulls for predation. To avoid damage while feeding, the skulls of pliosaurids like Peloneustes are highly akinetic, where the bones of the cranium and mandible were largely locked in place to prevent movement. The snout contains elongated bones that helped to prevent bending and bears a reinforced junction with the facial region to better resist the stresses of feeding. When viewed from the side, little tapering is visible in the mandible, strengthening it. The mandibular symphysis would have helped deliver an even bite and prevent the mandibles from moving independently. The enlarged coronoid eminence provides a large, strong region for the anchorage of the jaw muscles, although this structure is not as large in Peloneustes as it is in other contemporary pliosaurids. The regions where the jaw muscles were anchored are located further back on the skull to avoid interference with feeding. The kidney-shaped mandibular glenoid would have made the jaw joint steadier and stopped the mandible from dislocating. Pliosaurid teeth are firmly rooted and interlocking, which strengthens the edges of the jaws. This configuration also works well with the simple rotational movements that pliosaurid jaws were limited to and strengthens the teeth against the struggles of prey. The larger front teeth would have been used to impale prey while the smaller rear teeth crushed and guided the prey backwards toward the throat. With their wide gapes, pliosaurids would not have processed their food very much before swallowing.[42]: 193, 236–240

The numerous teeth of Peloneustes rarely are broken, but often show signs of wear at their tips. Their sharp points, slightly curved, gracile shape, and prominent spacing indicate that they were built for piercing. The slender, elongated snout is similar in shape to that of a dolphin. Both the snout and tooth morphologies led Noè to suggest that Peloneustes was a

Palaeoenvironment

Peloneustes is known from the Peterborough Member (formerly known as the Lower Oxford Clay) of the Oxford Clay Formation.

The Peterborough Member represents an

The surrounding land would have had a

Contemporaneous biota

There are many kinds of invertebrates preserved in the Peterborough Member. Among these are

A wide variety of fish are known from the Peterborough Member. These include the

Plesiosaurs are common in the Peterborough Member, and besides pliosaurids, are represented by

More pliosaurid species are known from the Peterborough Member than any other assemblage.

See also

References

- ^ a b c Cohen, K.M.; Finney, S.; Gibbard, P.L. (2015). "International Chronostratigraphic Chart" (PDF). International Commission on Stratigraphy.

- ^ S2CID 85851352.

- ^ a b c d e f Seeley, H. G. (1869). Index to the fossil remains of Aves, Ornithosauria, and Reptilia, from the secondary system of strata arranged in the Woodwardian Museum of the University of Cambridge. Cambridge, Deighton, Bell, and co. pp. 139–140.

- ^ a b Creisler, B. (2012). "Ben Creisler's Plesiosaur Pronunciation Guide". Oceans of Kansas. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- S2CID 131513080.

- ^ a b c d e Andrews, C. W. (1910). A descriptive catalogue of the marine reptiles of the Oxford clay. Based on the Leeds Collection in the British Museum (Natural History), London. Vol. 1. London: British Museum.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Tarlo, L. B. (1960). "A review of the Upper Jurassic pliosaurs". Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History). 4 (5): 145–189.

- ^ S2CID 128586645.

- ^ Bibcode:1892RSPS...51..119S.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Andrews, C. W. (1913). A descriptive catalogue of the marine reptiles of the Oxford clay. Based on the Leeds Collection in the British Museum (Natural History), London. Vol. 2. London: British Museum.

- ^ Andrews, C. W. (1895). "On the structure of the skull of Peloneustes philarchus, a pliosaur from the Oxford Clay". Annals and Magazine of Natural History; Zoology, Botany, and Geology. 16 (93): 242–256.

- ^ Jaccard, F. (1907). "Notes sur le Peloneustes philarchus Seeley du musée paléontologique de Lausanne". Bulletin de la Société Vaudoise des Sciences Naturelles (in French). 43 (160): 395–398.

- ^ a b c d Linder, H. (1913). "Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Plesiosaurier-Gattungen Peloneustes und Pliosaurus". Geologische und Palaeontologische Abhandlungen (in German). 11: 339–409.

- ^ S2CID 130045734.

- ^ a b Phillips, J. (1871). Geology of Oxford and the valley of the Thames. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ^ a b Lydekker, R. (1890). Catalogue of the fossil Reptilia and Amphibia in the British Museum (Natural History). Part IV. Containing the orders Anomodontia, Ecaudata, Caudata, Labyrinthodonta; and supplement. London: Trustees of the British Museum. p. 273.

- ^ a b Knutsen, E. M. (2012). "A taxonomic revision of the genus Pliosaurus (Owen, 1841a) Owen, 1841b" (PDF). Norwegian Journal of Geology. 92: 259–276.

- ^ Novozhilov, N. (1948). "Два новых плиозавра из нижнего волжского яруса Поволжья" [Two new pliosaurs from the Lower Volga beds Povolzhe (right bank of Volga)] (PDF). Doklady Akademii Nauk SSSR (in Russian). 60: 115–118.

- ^ a b Storrs, G. W.; Arkhangel'skii, M. S.; Efimov, V. M. (2000). "Mesozoic marine reptiles of Russia and other former Soviet republics". In Benton, M. J.; Shishkin, M. A.; Unwin, D. M.; Kurochkin, E. N. (eds.). The Age of Dinosaurs in Russia and Mongolia. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 187–209.

- ^ a b c O’Keefe, F. R. (2001). "A cladistic analysis and taxonomic revision of the Plesiosauria (Reptilia: Sauropterygia)". ActaZoologica Fennica. 213: 1–63.

- S2CID 55346096. Archived from the original(PDF) on 5 June 2020.

- S2CID 55353949.

- ^ S2CID 132852950.

- ^ S2CID 53642687.

- PMID 26715998.

- ^ a b Smith, A. S. (2013). "Morphology of the caudal vertebrae in Rhomaleosaurus zetlandicus and a review of the evidence for a tail fin in Plesiosauria" (PDF). Paludicola. 9 (3): 144–158.

- S2CID 128746688.

- ^ White, T. E. (1940). "Holotype of Plesiosaurus longirostris Blake and classification of the plesiosaurs". Journal of Paleontology. 14 (5): 451–467.

- ^ Perssons, P. O. (1963). "A revision of the classification of the Plesiosauria with a synopsis of the stratigraphical and geographical distribution of the group" (PDF). Lunds Universitets Arsskrift. 59 (1): 1–59.

- ^ S2CID 12528732.

- ^ Carpenter, K. (1997). "Comparative cranial anatomy of two North American Cretaceous plesiosaurs". In Callaway, I. M.; Nicholls, E. L. (eds.). Ancient Marine Reptiles. Academic Press. pp. 191–216.

- ^ PMID 22438869.

- ^ S2CID 19710180.

- PMID 23741520.

- PMID 27019740.

- S2CID 39217763.

- ^ S2CID 249034986.

- ^ S2CID 207053689.

- ^ PMID 31763069.

- ^ PMID 29892509.

- .

- ^ a b c d e f Noè, L. F. (2001). A taxonomic and functional study of the Callovian (Middle Jurassic) Pliosauroidea (Reptilia, Sauropterygia) (PhD). Chicago: University of Derby.

- ^ S2CID 129602868.

- ^ S2CID 85810360.

- PMID 35484197.

- S2CID 133806762.

- ^ a b c d Duff, K. L. "Palaeoecology of a bituminous shale – the Lower Oxford Clay of central England". Palaeontology. 18 (3): 443–482.

- ^ S2CID 129844404.

- ^ S2CID 130058981.

- ^ S2CID 131433536.

- doi:10.1130/G20356.1.

- ^ S2CID 131200898.

- ISBN 0901702463.

- PMID 33083104.

- .

- .

- ^ OCLC 2450768.

- S2CID 22915279. Archived from the original(PDF) on 9 June 2020.

- .

External links

Media related to Peloneustes at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Peloneustes at Wikimedia Commons