Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act

| |

| Nicknames | Pendleton Act |

|---|---|

| Enacted by | the 47th United States Congress |

| Citations | |

| Statutes at Large | ch. 27, 22 Stat. 403 |

| Legislative history | |

| |

The Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act is a

By the late 1820s, American politics operated on the

The Pendleton Civil Service Act provided for the selection of some government employees by competitive exams, rather than ties to politicians or political affiliation. It also made it illegal to fire or demote these government officials for political reasons and created the United States Civil Service Commission to enforce the merit system. The act initially only applied to about ten percent of federal employees, but it now covers most federal employees. As a result of the court case Luévano v. Campbell, most federal government employees are no longer hired by means of competitive examinations.

The namesake of the Pendleton Act is

Background

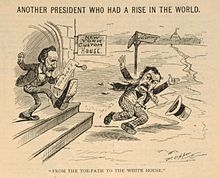

Since the presidency of Andrew Jackson, presidents had increasingly made political appointments on the basis of political support rather than on the basis of merit, in a practice known as the spoils system. In return for appointments, these appointees were charged with raising campaign funds and bolstering the popularity of the president and the party in their communities. The success of the spoils system helped ensure the dominance of both the Democratic Party in the period before the American Civil War and the Republican Party in the period after the Civil War. Patronage became a key issue in elections, as many partisans in both major parties were more concerned about control over political appointments than they were about policy issues.[3]

During the Civil War, Senator

According to historian Eric Foner, the advocacy of civil service reform was recognized by blacks as an effort that would stifle their economic mobility and prevent "the whole colored population" from holding public office.[8]

Provisions

The Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act provided for selection of some government employees by competitive exams rather than ties to politicians, and made it illegal to fire or demote some government officials for political reasons.[13] The act initially applied only to ten percent of federal jobs, but it allowed the president to expand the number of federal employees covered by the act.[14]

The law also created the United States Civil Service Commission to oversee civil service examinations and outlawed the use of "assessments," fees that political appointees were expected to pay to their respective political parties as the price for their appointments.[15] These assessments had made up a majority of political contributions in the era following Reconstruction.[16]

Legislative history

In 1880, Democratic Senator

Hayes did not seek a second term as president, and was succeeded by fellow Republican

Garfield's assassination by a deranged office seeker amplified the public demand for reform.

The party's disastrous performance in the 1882 elections helped convince many Republicans to support the civil service reform during the 1882

Aftermath

To the surprise of his critics, Arthur acted quickly to appoint the members of the newly created Civil Service Commission, naming reformers Dorman Bridgman Eaton, John Milton Gregory, and Leroy D. Thoman as commissioners.[14] The commission issued its first rules in May 1883; by 1884, half of all postal officials and three-quarters of the Customs Service jobs were to be awarded by merit.[29] During his first term, President Grover Cleveland expanded the number of federal positions subject to the merit system from 16,000 to 27,000. Partly due to Cleveland's efforts, between 1885 and 1897, the percentage of federal employees protected by the Pendleton Act would rise from twelve percent to approximately forty percent.[30] The act now covers about 90% of federal employees.[31]

Although state patronage systems and numerous federal positions were unaffected by the law, Karabell argues that the Pendleton Act was instrumental in the creation of a professional civil service and the rise of the modern bureaucratic state.[32] The law also caused major changes in campaign finance, as the parties were forced to look for new sources of campaign funds, such as wealthy donors.[33]

In January 1981, the Carter administration settled the court case Luévano v. Campbell, which alleged the Professional and Administrative Careers Examination (PACE) was racially discriminatory as a result of the lower average scores and pass rates achieved by Black and Hispanic test takers. As a result of this settlement agreement, PACE, the main entry-level test for candidates seeking positions in the federal government’s executive branch, was scrapped.[34] It has not been replaced by a similar general exam, although attempts at replacement exams have been made. The system which replaced the general PACE exam has been criticized as instituting a system of racial quotas, although changes to the settlement agreement under the Reagan administration removed explicit quotas, and these changes have "raised serious questions about the ability of the government to recruit a quality workforce while reducing adverse impact", according to Professor Carolyn Ban.[35][36]

In October 2020 President

See also

References

- ^ Searles, Harry; Mangus, Mike (April 9, 2012). George Hunt Pendleton (July 19, 1825 – November 24, 1889). Ohio Civil War Central. Retrieved January 27, 2022.

- ^ Matthews, Dylan (July 20, 2016). "Donald Trump and Chris Christie are reportedly planning to purge the civil service". Vox. Retrieved January 27, 2022.

- ^ Theriault, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Theriault, pp. 54–55, 60.

- ^ Paul, p. 71.

- ^ Davison, p. 164–165.

- ^ a b Hoogenboom, pp. 322–325; Davison, pp. 164–165; Trefousse, pp. 95–96.

- ^ Foner, Eric (1988). Reconstruction: America's Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877, p. 507. New York: Harper & Row.

- ^ Hoogenboom, pp. 353–355; Trefousse, pp. 100–101.

- ^ Hoogenboom, pp. 370–371.

- ^ Hoogenboom, pp. 382–384; Barnard, p. 456.

- ^ Paul, pp. 73–74.

- ^ "Digital History". www.digitalhistory.uh.edu.

- ^ a b Reeves 1975, pp. 325–327; Doenecke, pp. 102–104.

- ^ Karabell, pp. 104–107.

- ^ Theriault, p. 52.

- ^ a b Reeves 1975, pp. 320–324; Doenecke, pp. 96–97; Theriault, pp. 52–53, 56.

- ^ a b Karabell, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Ackerman 2003, pp. 305–308.

- ^ Reeves 1975, pp. 244–248; Karabell, pp. 61–63.

- ^ Karabell, pp. 62–63.

- ^ Reeves 1975, pp. 320–324; Doenecke, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Theriault, p. 56.

- ^ Doenecke, pp. 99–100; Karabell.

- ^ Theriault, pp. 57–59.

- ^ a b Reeves 1975, p. 324; Doenecke, pp. 101–102.

- ^ Theriault, pp. 59–60.

- ^ TO PASS S. 133, A BILL REGULATING AND IMPROVING THE U. S. CIVIL SERVICE. (J.P. 163). GovTrack.us. Retrieved February 11, 2022.

- ^ Howe, pp. 209–210.

- ^ Welch, 59–61

- ^ Glass, Andrew (January 16, 2018). "Pendleton Act inaugurates U.S. civil service system, Jan. 16, 1883". Politico.

- ^ Karabell, pp. 108–111.

- ^ White 2017, pp. 467–468.

- ^ US set to replace a civil service exam

- ^ "Let Me Call You Quota, Sweetheart". May 1981.

- JSTOR 976250.

- ^ ‘Stunning’ Executive Order Would Politicize Civil Service

- ^ "Executive Order on Protecting the Federal Workforce". January 22, 2021.

Works cited

- Ackerman, Kenneth D. (2003). Dark Horse: The Surprise Election and Political Murder of James A. Garfield. New York, New York: Avalon Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7867-1396-7.

- Barnard, Harry (2005) [1954]. Rutherford Hayes and his America. Newtown, Connecticut: American Political Biography Press. ISBN 978-0-945707-05-9.

- Davison, Kenneth E. (1972). The Presidency of Rutherford B. Hayes. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-8371-6275-1.

- Doenecke, Justus D. (1981). The Presidencies of James A. Garfield and Chester A. Arthur. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0208-7.

- Harrison, Brigid C., et al. American Democracy Now. McGraw-Hill Education, 2019.

- ISBN 978-0-7006-0641-2.

- Howe, George F. (1966) [1935]. Chester A. Arthur, A Quarter-Century of Machine Politics. New York: F. Ungar Pub. Co. ASIN B00089DVIG.

- ISBN 978-0-8050-6951-8.

- Paul, Ezra (Winter 1998). "Congressional Relations and Public Relations in the Administration of Rutherford B. Hayes (1877–81)". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 28 (1): 68–87. JSTOR 27551831.

- ISBN 978-0-394-46095-6.

- ISBN 978-0-8050-6907-5.

- Theriault, Sean M. (February 2003). "Patronage, the Pendleton Act, and the Power of the People". The Journal of Politics. 65 (1): 50–68. S2CID 153890814.

- Welch, Richard E. Jr. The Presidencies of Grover Cleveland (1988) ISBN 0-7006-0355-7

- ISBN 9780190619060.

Further reading

- Foulke, William Dudley (1919). Fighting the Spoilsmen: Reminiscences of The Civil Service Reform Movement. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons.

- ISBN 0-313-22821-3.

- Shipley, Max L. “The Background and Legal Aspects of the Pendleton Plan.” Mississippi Valley Historical Review 24#3 1937, pp. 329–40. online

- ISBN 0-8371-8755-9.

- Women's Auxiliary to the Civil Service Reform Association (1907). Bibliography of Civil Service Reform and Related Subjects (2nd ed.). New York.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)