Pennsylvania Station (1910–1963)

Pennsylvania Station | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Architectural style | Beaux-Arts | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other information | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Demolished (above ground) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | September 8, 1910 (LIRR) November 27, 1910 (PRR) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Key dates | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Construction | 1904–1910 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Demolition | 1963–1968 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reopened | 1968 (as Penn Station) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pennsylvania Station (often abbreviated to Penn Station) was a historic railroad station in

Designed by

Passenger traffic began to decline after World War II, and in the 1950s, the Pennsylvania Railroad sold the air rights to the property and shrank the railroad station. Starting in 1963, the above-ground head house and train shed were demolished, a loss that galvanized the modern historic preservation movement in the United States. Over the next six years, the below-ground concourses and waiting areas were heavily renovated, becoming the modern Penn Station, while Madison Square Garden and Pennsylvania Plaza were built above them. The sole remaining portions of the original station are the underground platforms and tracks, as well as scattered artifacts on the mezzanine level above it.

Design

Occupying two city blocks from Seventh Avenue to Eighth Avenue and from 31st to 33rd Streets, the original Pennsylvania Station building was designed by McKim, Mead & White.[3][4][5][6] The overall plan was created by Charles Follen McKim.[7] After McKim's health declined, William Symmes Richardson oversaw the completion of the design, while Teunis J. Van Der Bent oversaw the engineering.[8][7][9] Covering an area of about 8 acres (3.2 ha), it had frontages of 788 feet (240 m) along the side streets and 432 feet (132 m) long along the main avenues.[4][5][a] The land lot occupied about 800 feet (240 m) along 31st and 33rd Streets.[10]

Over 3,000,000 cubic yards (2,300,000 m3) of dirt had been excavated during construction.[7][11][12] The original structure was made of 490,000 cubic feet (14,000 m3) of pink granite, 60,000 cubic feet (1,700 m3) of interior stone, 27,000 short tons (24,107 long tons; 24,494 t) of steel, 48,000 short tons (42,857 long tons; 43,545 t) of brick, and 30,000 light bulbs.[11][12] The superstructure consisted of about 650 steel columns.[8] The building had an average height of 69 feet (21 m) above the street, though its maximum height was 153 feet (47 m).[13] Some 25 acres (10 ha)[6] or 28 acres (11 ha)[14] of track surrounded Penn Station.[14][6] At the time of Penn Station's completion, The New York Times called it "the largest building in the world ever built at one time".[15]

Exterior

The exterior of Penn Station was marked by

Entrances and colonnades

The building had entrances from all four sides.[4][10] The main entrance was at the intersection of Seventh Avenue and 32nd Street, at the center of the Seventh Avenue facade.[10] It was the most elaborate of Penn Station's entrances.[4] Above the center of the entrance, 61 feet (19 m) above the sidewalk, was a clock with 7-foot-diameter (2.1 m) faces.[10] Two plaques were placed above the arcade entrance. One plaque contained inscriptions of the names of individuals who had led the New York Tunnel Extension project, while the other included carvings of franchise dates and the names of contractors.[15][20]

Twin 63-foot-wide (19 m) carriageways at the northeast and southeast corners, modeled after Berlin's Brandenburg Gate, led to the two railroads served by the station.[21][15] One carriageway ran along the north side of the building, serving LIRR trains, while the other the south side served PRR trains.[15] The walls of each carriageway were flanked by pilasters for a distance of 279 feet (85 m).[21] Ramps spanned the carriageways and led into the waiting room and concourse.[21][22] The carriageways descended to the exit concourse at the middle of the station. From there, vehicles could travel to the baggage drop on the eastern end or return to Seventh Avenue. A separate passageway along the south side of the station carried baggage to the Eighth Avenue end of the station.[23]

An open colonnade was used along the north, east, and south facades.[24][21] The entirety of the east facade had a Doric-style colonnade.[10][25] The easternmost portions of the north and south facades, adjacent to the carriageways, also contained 230-foot-wide (70 m) colonnades.[15][21] Each column measured 35 feet (11 m) high by 4.5 feet (1.4 m) across.[10][4] The remainder of the facade contained pilasters rather than columns.[24][21][25] An approximately 45-foot-wide (14 m) section of the Eighth Avenue facade was divided into three large openings, which comprised a large rear entrance to the main concourse.[21]

The station contained four pairs of sculptures designed by Adolph Weinman, each of which consists of two female personifications, Day and Night. These sculptural pairs, whose figures were based on model Audrey Munson, flanked large clocks on the top of each side of the building.[26][27] Day was depicted with a garland of sunflowers in her hand, looking down at passengers, while Night was depicted with a serious expression and a cloak over her head.[28] The Day and Night sculptures were each accompanied by two small stone eagles.[29] There were also 14 larger, freestanding stone eagles placed on Penn Station's exterior.[30]

Interior

Penn Station was the largest indoor space in New York City and one of the largest public spaces in the world. The Baltimore Sun said in April 2007 that the station was "as grand a corporate statement in stone, glass and sculpture as one could imagine."[31] Historian Jill Jonnes called the original edifice a "great Doric temple to transportation".[32] The interior design was inspired by several sources, including French and German railway stations; St. Peter's Basilica; and the Bank of England.[17]

Entrance arcade

The main entrance on Seventh Avenue led to a shopping arcade that led westward into the station.[15][33] The arcade measured 45 feet (14 m) wide by 225 feet (69 m) long, with a similar width to 32nd Street.[4][34] Cassatt modeled the arcade after those in Milan and Naples, filling it with high-end boutiques and shops.[21][33] The stores were included because Cassatt wanted to give passengers a cultural experience upon their arrival in New York.[33] At the western end of the arcade, a statue of Alexander Johnston Cassatt stood in a niche on the northern wall where 40-foot-wide (12 m) stairs descended to a waiting room where passengers could wait for their trains.[4][33] There was also a statue of PRR president Samuel Rea directly across from Cassatt's statue, on the southern wall, which was installed in 1930.[35][36]

Main waiting room

The expansive waiting room, which spanned Penn Station's entire length from 31st to 33rd Streets, contained traveler amenities such as long benches, men's and women's smoking lounges, newspaper stands, telephone and telegraph booths, and baggage windows.[33] The main waiting room was inspired by Roman structures such as the baths of Caracalla, Diocletan, and Titus.[21][37] The room measured 314 feet 4 inches (95.81 m) long, 108 feet 8 inches (33.12 m) wide, and 150 feet (46 m) tall.[21][4][b] Additional waiting rooms for men and women, each measuring 100 by 58 feet (30 by 18 m), were on either side of the main waiting room.[21]

The room approximated the scale of St. Peter's Basilica in Rome. The lower walls were of travertine, while the upper walls were expressed in a steel framework clad in plaster, decorated to resemble the lower walls.[4][2][25] The travertine was sourced from Campagna in Italy.[38][40] This made Penn Station the first major American building to use travertine.[8] The north and south walls each contained small colonnades of six Ionic columns, which flanked the staircases on those walls.[39] There were also larger Corinthian columns on pedestals, measuring about 60 feet (18 m) tall from the tops of the pedestals to the tops of the capitals.[28][38] There were eight lunette windows on top of the waiting room's walls: one each above the north and south walls and three each above the west and east walls.[39] The lunettes had a radius of 38 feet 4 inches (11.68 m).[21][15]

The artist Jules Guérin was commissioned to create six murals for Penn Station's waiting room.[39][41][25] Each of his works were over 100 feet (30 m) high, placed above the tops of the Corinthian columns.[41][25] The murals themselves measured 25 feet (7.6 m) tall and 70 feet (21 m) across.[41] They contained maps depicting the extent of the PRR system.[39]

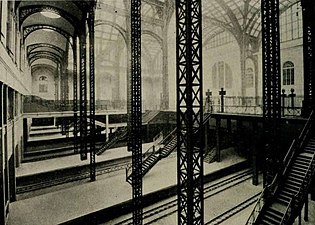

Concourses

Penn Station was one of the first rail stations to separate arriving and departing passengers on two concourses.[5] Directly adjoining the waiting room was the main concourse area for departing passengers, with stairs directly to each platform. The floor area of the main concourse was variously cited as having floor measurements of 314.33 by 200 feet (95.81 by 60.96 m)[4][33] or 208 by 315 feet (63 by 96 m).[25][38] This concourse was covered by glass vaults that were held up by a plain steel framework.[13][38][42][43] The glass roof measured 210 by 340 feet (64 by 104 m).[13] McKim wanted to give "an appropriate transition" between the decorated nature of the waiting room and the utilitarian design of the tracks below.[24] After the general shape of the vaults was determined, Purdy and Henderson designed the steelwork.[24][43] The steel frame was less heavy at the top.[24]

LIRR commuters could also use an entrance on the northern side, along 34th Street.[33] The LIRR commuter concourse was 18 feet (5.5 m) above the tracks.[3] There was an additional mezzanine level below the main concourse and waiting room for arriving passengers; it contained two smaller concourses, one for each railroad. The smaller northern mezzanine, used by the LIRR, connected to the LIRR platforms via short stairs and to the 34th Street entrance via escalators. The smaller southern mezzanine, used by the PRR, contained stairs and elevators between the PRR platforms and the level of the main concourse and waiting room.[33]

Running from north to south was a separate exit concourse, measuring 60 feet (18 m) wide. This concourse led to both 31st and 33rd Streets and was subsequently connected to the subway stations on Seventh and Eighth Avenues.[3][13] Two stairways and one elevator led to the exit concourse from each platform.[13]

Platforms and tracks

The tracks were variously cited as being 36 feet (11 m)

East of the station, tracks 5–21 merged into two three-track tunnels, which then merged into the East River Tunnels' four tracks. West of the station, at approximately Ninth Avenue, all 21 tracks merged into the North River Tunnels' two tracks. Tracks 1–4, the station's southernmost tracks, terminated at bumper blocks at the east end of the station, so they could only be used by trains from New Jersey.

History

Planning

Before 1910, there was no direct rail link from points west of the Hudson River into Manhattan.

Early proposals

Many proposals for a cross-Hudson connection were advanced in the late 19th century, but financial panics in the 1870s and 1890s scared off potential investors. In any event, none of the proposals advanced during this time were considered feasible.[51] The PRR considered building a rail bridge across the Hudson, but the state of New York insisted that a cross-Hudson bridge had to be a joint project with other New Jersey railroads, which were not interested.[52][53] The alternative was to tunnel under the river, but steam locomotives could not use such a tunnel due to the accumulation of pollution in a closed space, and the New York State Legislature prohibited steam locomotives in Manhattan after July 1, 1908.[54][55]

The idea of a Midtown Manhattan railroad hub was first formulated in 1901, when the Pennsylvania Railroad took interest in a new railroad approach recently completed in Paris. In the Parisian railroad scheme, electric locomotives were substituted for steam locomotives prior to the final approach into the city.[56][57] Cassatt adapted this method for the New York City area in the form of the New York Tunnel Extension project. He created and led the overall planning effort for it. The PRR, which had been working with the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) on the Tunnel Extension plans, made plans to acquire majority control of the LIRR so one new terminal could be built in Manhattan, rather than two.[57] The project was to include New York Penn Station; the North River Tunnels, crossing the Hudson River to the west; and the East River Tunnels, crossing the East River to the east.[57] Cassatt's vision for the terminal itself was inspired by the Gare d'Orsay, a Beaux-Arts style station in Paris.[56][1][58]

The original proposal for the station, which was published in June 1901, called for the construction of a bridge across the Hudson River between 45th and 50th Streets in Manhattan, as well as two closely spaced terminals for the LIRR and PRR. This would allow passengers to travel between Long Island and New Jersey without having to switch trains.[59] In December 1901, the plans were modified so that the PRR would construct the North River Tunnels under the Hudson River, instead of a bridge over it.[60] The PRR cited costs and land value as a reason for constructing a tunnel rather than a bridge, since the cost of a tunnel would be one-third that of a bridge.[61] The New York Tunnel Extension was quickly opposed by the New York City Board of Rapid Transit Commissioners who objected that they would not have jurisdiction over the new tunnels, as well as from the Interborough Rapid Transit Company, which saw the New York Tunnel Extension as a potential competitor to its as-yet-incomplete rapid transit service.[62] The city had initially declined to give the PRR a franchise because city officials believed that the PRR needed to grant thirteen concessions to protect city interests; the PRR ultimately conceded to nine of the city's requests.[63] The project was approved by the New York City Board of Aldermen in December 1902 by a 41–36 vote.[63]

Approved plans

In April 1902, Cassatt sent a telegram to Charles McKim of the New York architectural firm McKim, Mead & White.[7][64][49] According to one account, when McKim received the telegram, he said: "I suppose President Cassatt wants a new stoop for his house".[7][65] After McKim talked with Cassatt, the architect learned that he had received the commission for the new Pennsylvania Station.[65] McKim was pleased to receive the commission, writing to his friend Daniel Burnham, who had congratulated him.[7] The historian Mosette Broderick wrote that McKim faced an "internal conflict" because Burnham and Cassatt had collaborated on the development of Chicago Union Station, which indicated that Cassatt had some type of "loyalty" to Burnham.[65] McKim may have received the commission for New York Penn Station because of his friendship with Daniel Smith Newhall, the PRR's purchasing agent, who had praised McKim's work.[50]

The plans approved in December 1902 called for an "immense passenger station" on the east side of Eighth Avenue between 31st and 33rd Streets in Manhattan. The project was expected to cost over $100 million.

As part of the station's construction, the PRR proposed that the United States Postal Service construct a post office across from the station on the west side of Eighth Avenue. In February 1903, the U.S. government accepted the PRR's proposal and made plans to construct what would later become the Farley Post Office, which was also designed by McKim, Mead & White.[68] The PRR would also build a train storage yard in Queens east of Penn Station, to be used by both PRR trains from the west and LIRR trains from the east. The yard was to store passenger-train cars at the beginning or end of their trips, as well as to reverse the direction of the locomotives that pulled these train cars.[69]

Construction

Land acquisition

Land purchases for the station started in late 1901 or early 1902. The PRR purchased a site bounded by Seventh and Ninth Avenues between 31st and 33rd Streets. This site was chosen over other sites farther east, such as Herald Square, because these parts of Manhattan were already congested. Penn Station proper would be located along the eastern part of the site between Seventh and Eighth Avenue. The northwestern block, bounded by Eighth Avenue, Ninth Avenue, 32nd Street, and 33rd Street, was not part of the original plan.[70]

The condemnation of 17 city-owned buildings on the station's future site, an area of four blocks, began in June 1903.[71] All 304 parcels within the four-block area, which were collectively owned by between 225 and 250 entities, had been purchased by November 1903.[70] The PRR purchased land west of Ninth Avenue in April 1904, such that it owned all the land between Seventh and Tenth Avenues from 31st to 33rd Street. This land would allow the PRR to build extra railroad switches for the tracks around Penn Station.[72] The PRR also purchased land along the north side of the future station between 33rd and 34th Streets, so the company could create a pedestrian walkway leading directly to 34th Street, a major crosstown thoroughfare.[73] The properties between 33rd and 34th Street that the PRR had purchased were transferred to PRR ownership in 1908.[74] Clearing the site entailed "displacing thousands of residents from the largely African-American community in what was once known as the Tenderloin district in Manhattan."[75]

Early work

The details of the track layout were finalized by 1904.[7] A $5 million contract to excavate the site was awarded that June, marking the start of the construction.[76] Overall, some 500 buildings had to be demolished to make way for the station.[36] By early 1905, contractors were installing granite in the station's lower levels, and an adjacent power station on 31st Street was finished.[7] During this time, McKim's health began to decline as he experienced stress in his personal and professional life.[8] McKim withdrew from the project in 1906 as his health worsened, and Richardson replaced him as lead architect.[7][9][77]

Even as excavation proceeded, the federal government was still deciding whether to build a post office next to the PRR station. The PRR planned to turn over the

Completion and opening

The North River and East River Tunnels ran almost in a straight line between Queens and New Jersey, interrupted only by the proposed Pennsylvania Railroad station.[36] The technology for the tunnels connecting to Penn Station was so innovative that the PRR shipped an actual 23-foot (7.0 m) diameter section of the new East River Tunnels to the Jamestown Exposition in Norfolk, Virginia, in 1907, to celebrate the 300th anniversary of the nearby founding of the colony at Jamestown.[81] The same tube, with an inscription indicating that it had been displayed at the Exposition, was later installed under water and remains in use. Construction was completed on the Hudson River tunnels on October 9, 1906,[82] and on the East River tunnels on March 18, 1908.[83] Construction also progressed on Penn Station during this time.[7][45] Workers began laying the stonework for the station in June 1908; they had completed it thirteen months later.[84][45]

New York Penn Station was officially declared complete on August 29, 1910.

At the station's completion, the total project cost to the Pennsylvania Railroad for the station and associated tunnels was $114 million (equivalent to $2.7 billion in 2023[92]), according to an Interstate Commerce Commission report.[93][94] The railroad paid tribute to Cassatt, who died in 1906, with a statue designed by Adolph Alexander Weinman in the station's grand arcade,[95] subsequently moved to the Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania after the station's demolition.[96][97] An inscription below it read:[40][98]

Alexander Johnston Cassatt · President, Pennsylvania Railroad Company · 1899–1906 · Whose foresight, courage and ability achieved · the extension of the Pennsylvania Railroad System · into New York City

Operation

Early years

When Penn Station opened, it had a capacity of 144 trains per hour on its 21 tracks and 11 platforms. At the start of operations, there were 1,000 trains scheduled every weekday: of these, 600 were LIRR trains, while the other 400 were PRR trains.

The station put the Pennsylvania Railroad at a comparative advantage to its competitors offering service to the west and south. The Baltimore & Ohio (B&O), Central of New Jersey (CNJ), Erie, and the Lackawanna railroads began their routes at terminals in New Jersey, requiring travelers bound for New York City to use ferries or the interstate Hudson Tubes to traverse the Hudson River.[c] During World War I and the early 1920s, the rival B&O passenger trains to Washington, D.C., Chicago, and St. Louis also used Penn Station, initially by order of the United States Railroad Administration, until the Pennsylvania Railroad terminated the B&O's access in 1926.[104] Atypically for a public building, Penn Station was well maintained during its heyday. Such was the station's status that whenever the President of the United States arrived in New York by rail, he would arrive and depart on tracks 11 and 12.[105] Royalty and leaders of other countries also traveled via Penn Station.[36]

Over the next few decades, alterations were made to Penn Station to increase its capacity. The LIRR concourse, waiting room, amenities and platforms were expanded. Connections were provided to the

A Greyhound Lines bus terminal was built to the north of Penn Station, facing 34th Street, in 1935. However, within a decade, the bus terminal had gone into decline, and was frequented by low-level criminals and the homeless. The Greyhound bus terminal soon saw competition from the Port Authority Bus Terminal, located seven blocks north of Penn Station. Opened in 1950, it was intended to consolidate bus service. Greyhound resisted for almost a decade afterward, but by 1962 it had closed the Penn Station bus terminal and moved to the Port Authority Bus Terminal.[107]

Decline

The station was busiest during World War II: in 1945, more than 100 million passengers traveled through Penn Station.[1] The station's decline came soon afterward with the beginning of the Jet Age and the construction of the Interstate Highway System.[28][108] The PRR recorded its first-ever annual operating losses in 1947,[109] and intercity rail passenger volumes continued to decline dramatically over the next decade.[108] By the 1950s, its ornate pink granite exterior had become coated with grime.[75][110][111] During the decade, the PRR relied increasingly on real estate to keep it profitable.[112]

A renovation in the late 1950s covered some of the grand columns with plastic and blocked off the spacious central hallway with the "Clamshell", a new ticket office designed by Lester C. Tichy.[108][113] Architectural critic Lewis Mumford wrote in The New Yorker in 1958 that "nothing further that could be done to the station could damage it".[108][114] Advertisements surrounded the station's Seventh Avenue concourse, while stores and restaurants were crammed around the Eighth Avenue side's mezzanine. A layer of dirt covered the interior and exterior of the structure, and the pink granite was stained with gray.[108] Another architectural critic, Ada Louise Huxtable, wrote in The New York Times in 1963: "The tragedy is that our own times not only could not produce such a building, but cannot even maintain it."[115]

Demolition

The Pennsylvania Railroad optioned the air rights of New York Penn Station to real estate developer William Zeckendorf in 1954. He had previously suggested that the two-block site of the main building could be used for a "world trade center".[116][117][118] The option allowed for the demolition of the main building and train shed, which could be replaced by an office and sports complex. The station's underground platforms and tracks would not be modified, but the station's mezzanines would be reconfigured.[116][2] A blueprint for a "Palace of Progress" was released in 1955[119] but was not acted upon.[120]

Plans for the new

The architectural community in general was surprised by the announcement of the head house's demolition.

Under the leadership of PRR president

The first girders for Madison Square Garden were placed in late 1965,[129] and, by mid-1966, much of the station had been demolished except for the Seventh Avenue entrance.[130] By late 1966, much of the new station had been built. There were three new entrances: one from 31st Street and Eighth Avenue, another from 33rd Street and Eighth Avenue, and a third from a driveway running mid-block between Seventh and Eighth Avenues from 31st to 33rd Streets. Permanent electronic signs were being erected, shops were being renovated, new escalators were being installed, and platforms that were temporarily closed during renovations had been reopened.[131] A 1968 advertisement depicted architect Charles Luckman's model of the final plan for the Madison Square Garden Center complex.[132]

Impact

Although the demolition of the head house was justified as progressive at a time of declining rail passenger service, it also created international outrage.

The controversy over the original head house's demolition is cited as a catalyst for the architectural preservation movement in the United States,[113][134] particularly in New York City.[135][136] In 1965, two years after Penn Station's demolition commenced, the city passed a landmarks preservation act, thereby creating the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC).[137][138] New York City's other major railroad station, Grand Central Terminal, was also proposed for demolition in 1968 by its owner, Penn Central. Grand Central Terminal was ultimately preserved by the LPC, despite an unsuccessful challenge from Penn Central in 1978.[139][140][117]

Present day

The replacement Penn Station was built underneath Madison Square Garden at 33rd Street and Two Penn Plaza. The station spans three levels, with the concourses on the upper two levels and the train platforms on the lowest level. The two levels of concourses, while original to the 1910 station, were renovated extensively during the construction of Madison Square Garden and expanded in subsequent decades.

General reception of the replacement station has been largely negative. Comparing the new and old stations, Yale architectural historian

Times transit reporter Michael M. Grynbaum wrote that Penn Station was "the ugly stepchild of the city's two great rail terminals."[110] Along similar lines, Michael Kimmelman wrote in 2019 that while downsizing Penn Station and moving it underground may have made a modicum of sense at the time, in hindsight it was a sign that New York was "disdainful of its gloried architectural past." He also claimed that the remodeled station is not commensurate with its status as the main rail gateway to New York.[75]

The General Post Office, directly west of the station, remained largely intact through the 20th century;[135][136] the LPC had designated the post office as one of the city's earliest landmarks in 1966.[145] In the early 1990s, U.S. Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan began promoting a plan to build a replica of the historic Penn Station, since he had shined shoes in the original station during the Great Depression.[146] He proposed erecting it in the nearby Farley Post Office building.[147] The project, later renamed "Moynihan Train Hall", was split into two phases. The West End Concourse, opened in the eastern part of the former post office in June 2017.[148] The second phase, an expansion of Penn Station's facilities into parts of the post office building,[149] opened in January 2021.[150][151]

Surviving elements

Following the demolition of the original Penn Station, many of its architectural elements were lost or buried in the New Jersey Meadowlands. Some elements were salvaged and relocated. Additional architectural elements remain in the present-day station: some were covered over, while others remain visible throughout the current station.[29]

Ornaments and art

Eagles

Of the 22 eagle sculptures around the station exterior, the locations of all 14 larger, freestanding eagles are known.[30] Three remain in New York City: two at Penn Plaza along Seventh Avenue flanking the main entrance, and one at Cooper Union, Adolph Weinman's alma mater. Cooper Union's eagle had been located in the courtyard of the Albert Nerken School of Engineering at 51 Astor Place,[152] but was relocated in the summer of 2009, along with the engineering school, to a new academic building at 41 Cooper Square. This eagle is no longer visible from the street, as it is located on the building's eighth-floor green roof.[153]

Three eagles are on Long Island: two at the

Of the eight smaller eagles, which surrounded the four Day and Night sculptures,

Day and Night sculptures

Three pairs of the Day and Night sculptures have been located.[160] One of the four Day and Night sculptures still survives fully intact at Kansas City's Eagle Scout Memorial Fountain.[30][160] A Night sculpture was moved to the sculpture garden at the Brooklyn Museum.[30] The other pairs of Day and Night sculptures were discarded in the Meadowlands.[161] One of these pairs, recovered by Robert A. Roe, was stored at Ringwood State Park in Passaic County, New Jersey.[26][160]

In the late 1990s, NJ Transit wanted to install the sculptures at Newark Broad Street station.[26] However, this did not happen, and a writer for the website Untapped Cities found the sculpture pair in a Newark parking lot in mid-2017.[161] Another Day sculpture was found in 1998 at the Con-Agg Recycling Corporation plant in the Bronx;[29][160] the damaged sculpture had been stored at the recycling plant since at least the mid-1990s.[29]

Other artifacts

The Brooklyn Museum also owns part of one of the station's Iconic columns as well as some plaques from the station. The largest piece of the station that is known to had been salvaged, a 35-foot (11 m) Doric column, was transported upstate to

The statue of Samuel Rea still exists and is located outside the modern Penn Station entrance on Seventh Avenue.[164][165] Six bronze torchères from the waiting room were reinstalled in front of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine when the station building was demolished. By the 1990s, these lampposts had been moved to the cathedral's crypt due to deterioration.[166]

Layout features

Other small architectural details remain in the station. Some of the original staircases to platform level, with brass and iron handrails, still exist, though others have been replaced with escalators.

Penn Station Services Building

The Penn Station Services Building, located just south of the station at 242 West 31st Street between Seventh and Eighth avenues, was constructed in 1908 to provide electricity and heat for the station. The building measures 160 feet (49 m) long by 86 feet (26 m) tall, with a pink granite facade in the

The structure survived the demolition of the main station building, but was downgraded so that it only provided compressed air for the switches in the

In media

The original Pennsylvania Station has been featured in several works of media. For instance,

After Pennsylvania Station was demolished, it was recreated for a scene in the 2019 film

Gallery

-

The main waiting room

-

The concourse

-

The concourse and steps down to the tracks

-

The former Greyhound Bus terminal beside the station

References

Notes

- ^ Architectural historian Leland M. Roth gives a slightly different measurement of 780 by 430 feet (240 by 130 m).[3] A 1929 report gives a measurement of 788.75 by 430.50 feet (240.41 by 131.22 m).[10]

- ^ * Leland Roth gives a floor measurement of 102 by 278 feet (31 by 85 m) and a height of 147 feet (45 m) for the waiting room.[38]

- ^ The B&O and CNJ terminated at the Central Railroad of New Jersey Terminal in Jersey City.[101] The Erie and the Lackawanna terminated at Hoboken Terminal in Hoboken.[102] The Erie also used the Pavonia Terminal in Jersey City at one point.[103]

Citations

- ^ a b c d e McLowery, Randall (February 18, 2014). "The Rise and Fall of Penn Station – American Experience". PBS. Archived from the original on December 5, 2018. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- ^ from the original on May 24, 2018. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Roth 1983, p. 319.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Scientific American 1910b, p. 200.

- ^ a b c Droege 1916, p. 151.

- ^ a b c d Wilson 1983, p. 214.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Roth 1983, p. 318.

- ^ a b c d Broderick 2010, p. 464.

- ^ a b Wilson 1983, pp. 214, 216.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Clary & Williams 1929, p. 121.

- ^ a b Scientific American 1910a, pp. 398–399.

- ^ a b Cudahy 2002, pp. 74, 76.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Clary & Williams 1929, p. 125.

- ^ a b Macaulay-Lewis 2021, p. 25.

- ^ from the original on May 27, 2018. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- ^ Curbed NY. Archivedfrom the original on May 27, 2018. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- ^ a b Broderick 2010, p. 465.

- ^ Roth 1983, p. 324.

- ^ Churchill, James E. (March 23, 2021). "Historic Monel: the alloy that time forgot". Nickel Institute. Archived from the original on June 3, 2021. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- Brooklyn Daily Eagle. September 8, 1910. pp. 2–3. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 7, 2021. Retrieved May 24, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Clary & Williams 1929, p. 123.

- ^ Roth 1983, pp. 322, 323.

- ^ Roth 1983, p. 320.

- ^ a b c d e Roth 1983, p. 322.

- ^ a b c d e f g Wilson 1983, p. 216.

- ^ from the original on May 24, 2018. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- ^ a b c Cudahy 2002, p. 76.

- ^ a b c Macaulay-Lewis 2021, p. 27.

- ^ from the original on February 28, 2018. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Lee, Jennifer 8. (September 11, 2009). "New Aerie for a Penn Station Eagle". City Room. The New York Times Company. Archived from the original on September 13, 2010. Retrieved December 20, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Rasmussen, Frederick N. (April 21, 2007). "From the Gilded Age, a monument to transit". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 20, 2013.

- ISBN 978-0-670-03158-0.

- ^ from the original on May 23, 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ Clary & Williams 1929, pp. 121, 123.

- from the original on May 27, 2018. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Long Island Trains Inaugurated Service From Pennsylvania Station 25 Years Ago" (PDF). Jamaica Daily Press. September 8, 1935. p. 5. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 8, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ^ Cudahy 2002, p. 74.

- ^ a b c d e Roth 1983, p. 321.

- ^ a b c d e Macaulay-Lewis 2021, p. 26.

- ^ a b Clary & Williams 1929, p. 124.

- ^ from the original on May 23, 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ Cudahy 2002, p. 77.

- ^ a b Broderick 2010, pp. 464–465.

- ^ a b c d Scientific American 1910b, p. 201.

- ^ a b c Cudahy 2002, p. 75.

- ^ Scientific American 1910a, p. 399.

- ^ Mills, William Wirt (1908). Pennsylvania Railroad tunnels and terminals in New York City. Moses King. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- ^ a b c Cudahy 2002, p. 28.

- ^ a b c Macaulay-Lewis 2021, p. 24.

- ^ a b c Broderick 2010, p. 460.

- ^ "New York – Penn Station, NY (NYP)". the Great American Stations. Amtrak. 2016. Archived from the original on July 27, 2019. Retrieved May 19, 2019.

- ^ Kalmbach Publishing.

- The World's Work: A History of Our Time. XX: 13187–13204. Archivedfrom the original on June 27, 2014. Retrieved July 10, 2009.

- OCLC 11532538.

- ISBN 978-0-253-02799-3. Archivedfrom the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- ^ a b Broderick 2010, p. 461.

- ^ a b c Couper, William. (1912). History of the Engineering Construction and Equipment of the Pennsylvania Railroad Company's New York Terminal and Approaches. New York: Isaac H. Blanchard Co. pp. 7–16.

- ^ Brooklyn Daily Eagle. p. 456. Archivedfrom the original on December 28, 2019. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- from the original on May 22, 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- from the original on May 22, 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- from the original on May 22, 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- from the original on May 22, 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ from the original on May 22, 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ a b c Wilson 1983, p. 211.

- ^ a b c Broderick 2010, p. 459.

- ^ a b c Broderick 2010, p. 463.

- ^ Broderick 2010, pp. 461–462.

- from the original on May 22, 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- from the original on May 23, 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ from the original on May 23, 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- from the original on May 22, 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- from the original on May 23, 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- from the original on May 23, 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- from the original on May 23, 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ from the original on April 24, 2019. Retrieved April 25, 2019.

- from the original on May 23, 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ Macaulay-Lewis 2021, pp. 24–25.

- ^ from the original on May 23, 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- from the original on May 23, 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- from the original on May 23, 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ Industrial Magazine. Geo. S. Mackintosh. 1907. p. 79. Archived from the original on December 27, 2019. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- from the original on May 24, 2018. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- from the original on May 24, 2018. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- ^ Clary & Williams 1929, p. 127.

- from the original on May 23, 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- from the original on April 11, 2018. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- ^ "Big Tubes To-day Connect Brooklyn With Entire Country". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. October 27, 1910. p. 27. Archived from the original on December 9, 2021. Retrieved January 1, 2021 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Pennsylvania Station In New York's Busiest Spot" (PDF). Los Angeles Herald. November 22, 1910. p. 5 (col. 5). Archived (PDF) from the original on December 3, 2021. Retrieved December 3, 2021.

Beginning November 27, 1910, New York Trains Over Pennsylvania Lines Arrive at and Depart from Pennsylvania Station

- from the original on May 25, 2018. Retrieved May 24, 2018.

- Encyclopedia Britannica. March 1, 1976. Archivedfrom the original on April 5, 2019. Retrieved May 19, 2019.

- ^ Roth 1983, p. 325.

- Gross Domestic Product deflatorfigures follow the MeasuringWorth series.

- ^ Droege 1916, pp. 156–157.

- ^ a b Cudahy 2002, p. 29.

- ^ Staff (July 27, 1910). "Cassatt Statue in Station. The Only One to Stand in the New Pennsylvania Terminal Here". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 27, 2014. Retrieved February 11, 2017.

- ISBN 978-0-253-03934-7. Archivedfrom the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved February 15, 2021.

- ISBN 978-0-8117-2622-1. Archivedfrom the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ "In Memory of Great Railroad Presidents". Philadelphia and Reading Railway Men. 11. Young Men's Christian Association, Reading Railway Department: 341. 1910. Archived from the original on September 15, 2021. Retrieved September 15, 2021.

- ^ Cudahy 2002, p. 30.

- ^ Wilson 1983, pp. 211, 214.

- ^ "Jersey City Central Railroad Terminal" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. July 24, 1973. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 6, 2021. Retrieved May 19, 2018.

- ^ "Erie-Lackawanna Railroad Terminal at Hoboken" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. July 24, 1973. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 8, 2021. Retrieved May 19, 2018.

- (PDF) from the original on July 20, 2021. Retrieved February 15, 2018.

- ISBN 0-89778-155-4.

- ^ Cudahy 2002, p. 78.

- ^ Schotter, H. W. (1927). The Growth and Development of The Pennsylvania Railroad Company 1846–1926. p. 74.

- from the original on January 6, 2012. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- ^ from the original on May 23, 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- from the original on May 23, 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ a b c Grynbaum, Michael M. (October 18, 2010). "The Joys and Woes of Penn Station at 100". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 15, 2013. Retrieved February 3, 2013.

- ^ a b Roth 1983, p. 326.

- ^ Broderick 2010, pp. 465–466.

- ^ from the original on September 6, 2018. Retrieved September 6, 2018.

- ^ Mumford, Lewis (June 7, 1958). "The Disappearance of Pennsylvania Station". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on May 23, 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ from the original on July 7, 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ from the original on May 29, 2018. Retrieved May 29, 2018.

- ^ a b c Mooney, Richard E. (August 14, 2017). "End of a landmark: The demolition of Old Penn Station". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on May 24, 2018. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- ^ Associated Press (November 28, 1954). "Realty Firm Options Penn Station Air Rights" (PDF). Knickerbocker News. p. 10A. Retrieved May 28, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- from the original on September 5, 2018. Retrieved September 4, 2018.

- from the original on May 23, 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ from the original on May 8, 2022. Retrieved July 13, 2010.

- from the original on January 20, 2012. Retrieved January 16, 2010.

- ^ Plosky, Eric J. (1999). "The Fall and Rise of Pennsylvania Station -Changing Attitudes Toward Historic Preservation in New York City" (PDF). Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 6, 2015. Retrieved February 22, 2015.

- ^ Roth 1983, pp. 326–327.

- from the original on May 23, 2018. Retrieved May 22, 2018.

- ^ Cudahy 2002, p. 73.

- ^ a b "New York – Penn Station, NY (NYP)". greatamericanstations.com. Archived from the original on October 7, 2013. Retrieved October 5, 2013.

- from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- from the original on May 22, 2020. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- ^ "Madison Square Garden Center – a new international landmark". nyc-architecture.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2013. Retrieved January 29, 2020.

- ^ Roth 1983, p. 327.

- ^ "Laying the Preservation Framework: 1960–1980". Cultural Landscapes (U.S. National Park Service). April 24, 1962. Archived from the original on September 6, 2018. Retrieved September 6, 2018.

- ^ a b Macaulay-Lewis 2021, p. 28.

- ^ a b Broderick 2010, p. 466.

- ^ Bryant, Nick (May 28, 2015). "New York City's ugly saviour". BBC News. Archived from the original on September 6, 2018. Retrieved September 6, 2018.

- from the original on November 16, 2018. Retrieved September 6, 2018.

- ^ Serratore, Angela (June 26, 2018). "The Preservation Battle of Grand Central". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on September 6, 2018. Retrieved September 6, 2018.

- ^ Weinstein, Jon (January 29, 2013). "Grand Central Terminal At 100: Legal Battle Nearly Led To Station's Demolition". NY1. Archived from the original on June 17, 2013.

- from the original on May 28, 2015. Retrieved March 6, 2010.

- from the original on December 27, 2009. Retrieved February 7, 2010.

- ^ "Station Directory – Penn Station, NY" (PDF). NJ Transit. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 30, 2018. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- from the original on April 25, 2009. Retrieved November 26, 2007.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 27, 2022.

- ^ Michaelson, Juliette (July 1, 2006). "A narrative history of Penn Station and Moynihan Station". Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 26, 2013.

- ^ Laura Kusisto; Eliot Brown (March 2, 2014). "New York State Pushes for Penn Station Plan". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on March 7, 2014. Retrieved December 28, 2018.

- Curbed NY. Archivedfrom the original on June 15, 2017. Retrieved June 23, 2017.

- from the original on September 30, 2016. Retrieved September 28, 2016.

- ^ "Governor Cuomo Announces New Main Entrance to Penn Station and Expansion of LIRR Concourse". Metropolitan Transportation Authority. September 6, 2018. Archived from the original on September 6, 2018. Retrieved September 7, 2018.

- ^ "Midtown block could permanently close for Penn project". AM New York Metro. September 6, 2018. Archived from the original on September 7, 2018. Retrieved September 7, 2018.

- ^ a b c d von Meistersinger, Toby (September 4, 2007). "Keep an Eagle Eye Out for Penn Station Eagles". Gothamist. Archived from the original on January 10, 2010. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- ^ "News Briefs: Cooper Union Eagle Takes Flight" (PDF). At Cooper Union (Summer 2009): 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 19, 2011. Retrieved July 29, 2012.

- NBC New York. Archivedfrom the original on May 24, 2018. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- ^ a b c Dunlap, David W. (May 6, 2011). "Bird Week – A Penn Station Eagle in Poughkeepsie". City Room. The New York Times Company. Archived from the original on October 1, 2019. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- ^ a b Dunlap, David W. (July 5, 2011). "After Half a Century, a Penn Station Eagle Returns". City Room. The New York Times Company. Archived from the original on April 16, 2019. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- ^ "Penn Station eagles come to roost in the Highlands". Hidden NJ. October 14, 2011. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- ^ "Eagle Scout Memorial Fountain". KC Parks and Rec. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ "Gillham fountain helped launch architecture preservation movement". Midtown KC Post. March 11, 2013. Archived from the original on January 7, 2021. Retrieved January 6, 2021.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-393-73078-4. Archivedfrom the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved February 29, 2020.

- ^ a b Rivers, Justin (July 12, 2017). "New Original Penn Station Eagle Remnants Found in Newark, NJ Parking Lot". Untapped Cities. Archived from the original on May 24, 2018. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 12, 2018.

- ^ a b c Ruttle, Craig (August 1, 2017). "Penn Station's history is hidden in plain sight". AM New York Metro. Archived from the original on May 27, 2018. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- ^ from the original on November 12, 2017. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- ^ Tauranac, John (February 12, 1999). "Lost New York, Found in Architecture's Crannies". The New York Times. Retrieved January 3, 2024.

- ^ from the original on June 26, 2020. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ^ staff/jen-carlson (July 27, 2015). "A Piece Of The Original Penn Station Is Still Standing On 31st Street". Gothamist. Archived from the original on June 30, 2020. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ^ Siff, Andrew (January 6, 2020). "Cuomo: 8 New Tracks to Be Added to NY Penn Station". NBC New York. Archived from the original on January 6, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ Higgs, Larry (January 6, 2020). "Penn Station expansion will make getting to NYC easier, Cuomo says". NJ.com. Archived from the original on January 6, 2020. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7679-1634-9. Archivedfrom the original on June 17, 2021. Retrieved June 6, 2021.

- ^ "The Clock MGM Production No. 1331". Archived from the original on June 26, 2020. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ISBN 978-1-62356-421-6. Archivedfrom the original on June 6, 2021. Retrieved June 6, 2021.

- ISBN 978-0-300-25561-4. Archivedfrom the original on June 18, 2021. Retrieved June 6, 2021.

- ISBN 978-0-8242-0763-2. Archivedfrom the original on May 9, 2016. Retrieved June 6, 2021.

- ^ Young, Michelle (October 3, 2019). "How the Lost Penn Station Was Recreated for the Movie Motherless Brooklyn". Untapped New York. Archived from the original on October 5, 2019. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- ^ Mitchell, Alex (March 10, 2020). "How the CGI experts from 'Motherless Brooklyn' brought back the old, iconic Penn Station on film". AM New York. Archived from the original on June 30, 2020. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

Sources

- Broderick, Mosette (2010). Triumvirate: McKim, Mead & White: Art, Architecture, Scandal, and Class in America's Gilded Age. Alfred A. Knopf. OCLC 698447571.

- Clary, Martin; Williams, Arthur (1929). Mid-Manhattan: That Section of the Greater City of New York Between Washington Square and Central Park and the East and North Rivers in the Borough of Manhattan. Forty-Second Street Property Owners and Merchants Association. pp. 120–127.

- "Completion of the Pennsylvania Tunnels and Terminal Station". Scientific American. Library of American civilization (v. 102). Munn & Company. May 14, 1910.

- Cudahy, Brian J. (2002), Rails Under the Mighty Hudson (2nd ed.), New York: OCLC 911046235

- Droege, John A. (1916). Passenger Terminals and Trains. McGraw-Hill. p. 156.

droege Passenger Terminals and Trains.

- Macaulay-Lewis, Elizabeth (2021). Antiquity in Gotham: The Ancient Architecture of New York City. Fordham University Press. OCLC 1176326519.

- "Opening of the Pennsylvania Terminal Station in New York". Scientific American. Library of American civilization (v. 103). Munn & Company. September 10, 1910.

- Roth, Leland (1983). McKim, Mead & White, Architects. Harper & Row. pp. 314–327. OCLC 9325269.

- Stern, Robert A. M.; Gilmartin, Gregory; Massengale, John Montague (1983). New York 1900: Metropolitan Architecture and Urbanism, 1890–1915. New York: Rizzoli. OCLC 9829395.

- Wilson, Richard Guy (1983). McKim, Mead & White, architects. New York: Rizzoli. OCLC 9413129.

External links

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. NY-5471, "Pennsylvania Station", 22 photos, 7 data pages

- Pennsylvania Railroad Company (1910). Pennsylvania station in New York City.

- "Pennsylvania Station". SkyscraperPage.

- Pennsylvania Station at Structurae

- The Rise and Fall of Penn Station, American Experience, PBS (February 2014)

- Architectural drawings and photographs of the station (plates 300–310)