Penrith, Cumbria

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2007) |

| Penrith | |

|---|---|

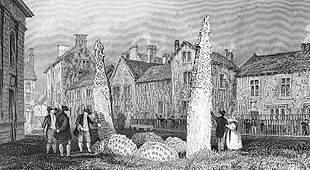

The Market Square | |

Flag | |

Location within Cumbria | |

| Population | 16,984 (2021 census)[1] |

| Demonym | Penrithian |

| OS grid reference | NY515305 |

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | PENRITH |

| Postcode district | CA10, CA11 |

| Dialling code | 01768 |

| Police | Cumbria |

| Fire | Cumbria |

| Ambulance | North West |

| UK Parliament | |

Penrith (/ˈpɛnrɪθ/, /pɛnˈrɪθ/ PEN-rith, pen-RITH) is a market town and civil parish in the Westmorland and Furness district of Cumbria, England. It is less than 3 miles (5 km) outside the Lake District National Park and about 17 miles (27 km) south of Carlisle. It is between the Rivers Petteril and Eamont and just north of the River Lowther. The town had a population of 15,181 at the 2011 census.[2] It is part of historic Cumberland.

From 1974 to 2015, it was an unparished area with no local council. A civil parish was reintroduced on 1 April 2015 with the first election for Penrith Town Council on 7 May 2015. The town was previously part of the 1974-created Eden District until 2023.

Toponymy

The etymology of "Penrith" has been debated. Several writers argue for the Cumbric or Welsh pen "head, chief, end" (both noun and adjective) with the Cumbric rid, Welsh rhyd "ford", to mean "chief ford", "hill ford", "ford end", or Whaley's suggestion: "the head of the ford" or "headland by the ford".[3][4][5]

The centre of Penrith, however, lies about 1 mile (1.6 km) from the nearest crossing of the River Eamont at Eamont Bridge. An alternative has been suggested consisting of the same pen element meaning "head, end, top" + the equivalent of Welsh rhudd "crimson".[6][7] Research on the medieval spelling variants of Penrith also suggests this alternative etymology.[8] The name "red hill" may refer to Beacon Hill, to the north-east of today's town. There is also a place called Redhills to the south-west, near the M6 motorway, and a place called Penruddock, about 6 miles (9.7 km) west of Penrith. These names all reflect the local geology, as red sandstone is abundant in the area and was used for many buildings in Penrith.

Prehistory

The origins of Penrith go far back in time. There is archaeological evidence of "early, concentrated and continuous settlement" in the area.[M 1] The Neolithic (c. 4500–2350 BCE) or early-Bronze Age (c. 2500–1000 BCE) sites at nearby Mayburgh Henge, King Arthur's Round Table, Little Round Table, Long Meg and Her Daughters, and Little Meg, and the stone circles at Leacet Hill and Oddendale are some of the visible traces of "one of the most important groups of prehistoric ritual sites in the region." In addition there have been various finds (stone axes, hammers, knives) and carvings found in the Penrith area.[M 2]

For the

Roman period

Penrith itself was not established by the Romans, but they recognised the strategic importance of the place, especially near the confluence of the rivers Eamont and Lowther, where the Roman road crossing the Pennines (the present A66) came through. In doing so, they built the fort at

The

The

The two forts close to where Penrith is today would have had a vicus, an ad-hoc civilian settlement nearby, where farmers supplying food to the forts, and traders and others supplying goods and services lived and died. There is evidence of continuous settlement throughout the Roman period and into the post-Roman era.[M 5]

History

Penrith's history has been defined primarily by its strategic position on vital north–south and east–west communications routes. This was especially important in its early history, when Anglo-Scottish relations were fraught. Furthermore, Penrith was a Crown possession in its early phase, though often granted to favoured noble families. It did not become a chartered borough or a municipal corporation and had no representation in Parliament. It also gained growth from its proximity to the Inglewood Forest and to the fertile Eden valley, and largely depended upon agriculture, especially cattle rearing and droving.

Early medieval period

After the departure of the Romans (c. 450 CE), the north became a patchwork of warring Celtic tribes (Hen Ogledd). One of these may have been Rheged, perhaps with a centre in the Eden valley and covering the area formerly held by the Carvetti. However, this has been disputed by historians. The Rheged Centre, just outside Penrith, commemorates the name.

During the 7th century, the region was invaded by the

From about 870, the area became subject to Viking settlement by Norse from Dublin and the Hebrides, along with Danes from Yorkshire. Settlements with names ending in "-by" ("village") and "-thorpe" ("hamlet") were largely on higher ground – the Vikings were pastoralists, the Angles arable farmers. Examples are Melkinthorpe, Langwathby, Lazonby, and Ousby. Little and Great Dockray (not to be confused with the nearby village Dockray) in Penrith itself are Norse names.[M 7]

The Penrith Hoard of Viking silver brooches was found in the Eden valley at Flusco Pike, Penrith, as were 253 pieces of silver at Lupton.[14]

Two cross-shafts and four

On 12 July 927,

Penrith may have been founded before the arrival of the Normans. A ditched oval enclosure surrounding the area now occupied by St Andrew's Church (a burh - hence "Burrowgate") has been excavated. A church on the site may date back to the time of Bishop Wilfrid, (c. 670s) whose patron saint was Saint Andrew.[M 10]

Later medieval period: Normans and Plantagenets

The Norman conquest of north Cumbria took place in 1092 under

Membership of the group fluctuated over time. In 1187 a sub-set including Penrith, Langwathby, Great Salkeld, Gamblesby, Glassonby and Scotby was referred to as the Honour of Penrith.[M 13] From 1242 to 1295, the Honour of Penrith (created "the liberty of Penrith" by the Treaty of York in 1237) was in the hands of the King of Scots, in return for renouncing his claims to Northumberland, Cumberland and Westmorland. King Henry III had been reluctant to cede Penrith to the Scots, as it was a good source of Crown income: the right to hold a market and fair was granted in 1223 by Henry, and arable farming produced good yields and taxes.[M 14] Tensions between the English Crown's agents in Cumberland and the Scottish agents attempting to defend the rights of the Scottish king and his tenants in the liberty of Penrith, may have influenced the mindset of the Scots leading up to the outbreak of the Wars of Scottish Independence.[16]

With the Wars of Scottish Independence, Penrith suffered destruction by Scottish forces in 1296 (William Wallace), 1314, 1315–1316 and 1322 (Robert the Bruce). Meanwhile climatic change caused poor harvests. Penrith went from incipient economic growth in the early 14th century to poverty by the third decade.[M 17] Recovery in the 1330s was again reversed by the devastating Scottish raid of 1345 (David II of Scotland) and the Black Death of 1348–1349 and subsequent years. However, Penrith, Castle Sowerby and the other manors were valuable as a source of royal income, paying debts the Crown owed to those leading the fight against the Scots, such as Roger de Leybourne, Anthony de Lucy and Andrew Harclay, 1st Earl of Carlisle.[M 18]

There is evidence of a protective wall built round the town after the Scottish raid of 1345. This was strengthened in 1391 by the townspeople and Penrith's patron, William Strickland, Bishop of Carlisle, after another Scottish raid by the 1st Earl of Douglas in 1380, and others in 1383 and 1388, when Brougham Castle was probably destroyed as well.[M 19] It is thought that Strickland built and strengthened the "pele tower" in Benson Row, behind Hutton Hall. He also endowed a chantry (1395) in St Andrew's Church, (where the chantry priest may have taught music and grammar), and created Thacka Beck, diverting clean water from the River Petteril, which was notably valuable for the tanning and related industries.[M 20]

Strickland shared power in Penrith with the

Early modern period (1485–1714)

Tudor period

The Tudor period saw the centralising tendencies of the Yorkist government continued. The English Reformation, economic and social progress, educational change, the rise of the non-noble landed gentry and the depredations of the plague all affected Tudor England, and Penrith was no exception.[M 22]

The eclipse of the Nevilles and Percies by the end of the

Penrith people were involved in a rebellion of 1536/1537 known as the Pilgrimage of Grace. Eight town residents were executed as a result. The motives seem to have been partly religious, partly to do with a desire for more English government protection against Scottish raids.[M 24]

The reformation went on apace afterwards – the Augustinian Priory was dissolved and the two chantry bequests closed later. The Strickland bequest partly funded the

Penrith was not involved in the

However, there may have been a substantial underclass as well, as shown by possible poverty and poor nutrition causing a high death rate in 1587, when there may have been a typhus epidemic. The Bubonic plague may have caused some 615 deaths in 1597–1598, according to the vicar's register (2,260 according to a brass plaque inside St Andrew's Church).[M 26]

Stuart period

Penrith in Stuart times was affected by political and religious upheavals that saw the English Civil War, the Commonwealth and the Glorious Revolution, but was spared any fighting. It also escaped the witch-craze phenomenon that afflicted other parts of England. The Union of the Crowns and suppression of the reiver clans such as the Grahams, gave Penrith relief from Scottish raiding and a boost to Penrith's commercial prosperity. James VI and I and his entourage of 800 visited Brougham Castle in 1617, which boosted commerce. However, Penrith's crossroads position on the north–south and east–west routes made it vulnerable to starving vagrants bringing disease. This plus a national food shortage may have led to a typhus epidemic in 1623.[M 27]

During the Civil War, Penrith's gentry were mostly Royalist, but Penrithians seem to have been neither for nor against the King. During the first war (1642–1646), General Leslie took over Brougham Castle for the Covenanters and Penrith became a supply centre for Parliament. In the second civil war starting in 1648, Brougham and Penrith castles were strategic assets. Major-General Lambert, the Parliamentary commander, took over Penrith in June 1648 until forced out by Scottish royalists aided by Sir Philip Musgrave of Edenhall. The Covenanters supported the future Charles II after 1648. He stayed at Carleton Hall in 1651 on his way south to defeat at the Battle of Worcester.[M 28]

Because Penrith lacked borough or corporation status, governance fell on the local nobility, gentry and clergy, (such as Hugh Todd). During the Commonwealth, Presbyterian "Godly rule" was administered at St Andrew's Church by the local Justice of the peace, Thomas Langhorne, who had bought Lowther's Newhall/Two Lions house.[M 29] Meanwhile, Penrith benefited from work on restoration of Brougham and other castles, and by charitable donations undertaken by Lady Anne Clifford.[M 30] The gradual rise in religious toleration eventually saw in 1699 the establishment, by the Quakers, of Penrith's second place of worship, the Friends' Meeting House in Meeting House Lane.[M 31]

Leading gentry of Cumberland and Westmorland gathered at the George Inn on 4 January 1688 at the behest of Lord Preston, the Lord Lieutenant of Cumberland and Westmorland. He was attempting to gauge the views of leading figures in the counties (deputy-lieutenants, and J.P.s) on the intention of King James II to introduce greater religious toleration. Partly due to efforts by John Lowther, 1st Viscount Lonsdale, the attendees were persuaded to give a non-committal reply. The Whig Lowther went on to contribute to securing the two counties for King William in the Glorious Revolution and advancing his career, unlike his local (Tory) rival Christopher Musgrave of Edenhall who had been more dilatory in his support for William. This exemplified local politics feeding into national politics.[M 32][18]

The economy of Penrith "continued to rely on cattle rearing, slaughtering and the processing of cattle products" (leather goods, tanning, shoemaking).[M 33]

Local government before 1974

| Penrith Urban District | |

|---|---|

| History | |

| • Created | 1894 |

| • Abolished | 1974 |

| • Succeeded by | Eden District |

| Status | Urban district |

| • HQ | Penrith Town Hall |

Penrith was an

In the 1920s

Governance

UK Parliament

Penrith is in the

Local government

Since 2023, Penrith has had two levels of local government – Westmorland and Furness unitary authority (see below) and Penrith parish (town).

Until 2023, for county purposes, it was governed by Cumbria County Council, whose social services and education departments used to have area offices in the town. It was the seat of administration for Eden District Council, one of the largest districts by area in England and the most sparsely populated. It was based at offices in Penrith Town Hall and at the building now known as Mansion House, formerly Bishop Yards House.

A civil parish of Penrith was first formed in 1866. Between 1894 and 1974 the Urban District council acted as the parish council, but on its abolition, its successor authority, Eden District Council, decided that Penrith would become an unparished area under the district council's direct control. In 2014 a referendum was held open to all registered voters in the unparished area of Penrith to see if they wanted a parish council for Penrith, and the result was in favour. The first elections to this were held on 7 May 2015. Initially the town council was based in offices in St Andrews Place, but since 2017 it has taken the former county council offices in Friargate.

Former local government divisions

For electing

- Penrith West: Castletown and parts of the town centre and Townhead

- Penrith North: part of the town centre, the New Streets, most of Townhead and the outlying settlements of Roundthorn, Bowscar and Plumpton Head

- Penrith South: Wetheriggs, Castle Hill, a small part of the town centre, part of Eamont Bridge and part of the Bridge Lane/Victoria Road area

- Penrith East: part of the town centre, Scaws, Carleton Parklands and Barco

- Penrith Carleton (formerly part of Penrith East): Carleton Village, High Carleton, Carleton Heights, Carleton Hall Gardens

- Penrith Pategill (formerly part of Penrith East): Pategill, Carleton Drive/Place, Tynefield Drive/Court and part of Eamont Bridge

Penrith West and South wards made up the Penrith West Electoral Division of Cumbria County Council, while East, Carleton and Pategill wards combine as Penrith East division. Penrith North, along with the rural Lazonby ward, made up Penrith North division.

2023 changes to Local Government

In 2023 Cumbria County Council and the 6 District councils within the county were abolished and replaced by two new unitary authorities. Eden along with South Lakeland and the Borough of Barrow-in-Furness became the new unitary District of Westmorland and Furness. The first elections to the new authority took place in May 2022. Penrith was divided into two new wards for the new council – Penrith North (the former Eden council wards of Penrith North and East) and Penrith South (the former West, South, Carleton and Pategill wards).

A nascent campaign has arisen, demanding that Penrith be included within

Geography

Watercourses

Divisions and suburbs

Castletown

Castletown, west of the

There was until March 2010 a pub in the suburb, The Castle Inn, and in previous years a sub-post office, a

The suburb has a

Townhead

Townhead is the town's northern area, including the Fair Hill district and the Voreda Park or Anchor

New Streets

New Streets marks an area between Townhead and Scaws on the side of the Beacon Hill or Fell, with steep streets of some terraced housing, but mainly detached and semi-detached houses of the late 19th century. These streets from north to south are Graham, Wordsworth, Lowther and Arthur Street. The term sometimes includes Fell Lane, which is actually the ancient east road from Penrith town centre to Langwathby), and Croft Avenue and Croft Terrace (from about 1930), which were not developed till later. At the foot is Drovers Lane, once Back Lane, subdivided into Drovers Terrace, Wordsworth Terrace, Lowther Terrace, Bath Terrace, Arthur Terrace, Lonsdale Terrace, and finally Meeting House Lane. Along the top is Beacon Edge, with extensive views over the town and towards the Lake District. Until the turn of the 20th century, Beacon Edge was known as Beacon Road. Apart from the streets up the fellside there are some that link smaller housing developments between them.

The fellside is known to have been used as a burial ground for victims of bubonic plague, which struck Penrith down the centuries. There are also areas that still have farming names, such as a wooded enclosure in Fell Lane known as the Pinfold (or Pinny) – once a pound for stray animals until owners paid to reclaim them. One lane off Beacon Edge is still

Scaws

The Scaws Estate was built by Penrith Urban District Council after World War II on land hitherto known as the Flatt Field and Scaws Farm, as part of the Lowther Estates. Scaws Farm is now Coldsprings Farm, the name being changed after a murder there. Later some private housing was built on higher parts of the estate.

Beaconside Primary School stands in the centre of the estate, where there were once three corner shops and a launderette. Adjoining Scaws are the private Barcohill and Meadow Croft housing estates.

Carleton

Carleton was once a separate settlement of houses along one side of the A686 road following the boundary of the built-up area. Carleton Hall holds the headquarters of the Cumbria Constabulary.[23] The area is the home of Carelton Banks FC, colloquially the Pinks.[24]

Pategill

Adjoining Carleton is the Pategill Housing Estate. It began as a council estate on land once part of the Carleton Hall estate and is still mostly owned by

Wetheriggs

The Wetheriggs, Skirsgill and Castle Hill or Tyne Close areas were developed in the 1920s by Penrith Urban District Council on land formerly known as Scumscaw. The first private housing was developed in Holme Riggs Avenue and Skirsgill Gardens just before World War II. Further development did not start until the 1960s and 1970s, on land between Wetheriggs Lane and Ullswater Road. Not until the late 1980s were the two roads connected by the Clifford Road extension, which saw the Skirsgill area developed. There are three schools: Ullswater Community College. North Lakes Junior and Queen Elizabeth Grammar School (QEGS). The Crescent in Clifford Road holds sheltered accommodation for the elderly. There was once a shop at the junction of Huntley Avenue and Clifford Road and another at the foot of Holme Riggs Avenue. The large North Lakes Hotel and Spa stands at the junction of Clifford and Ullswater Roads, overlooking the Skirsgill Junction 40 Interchange of the M6 motorway, A66 and A592 roads.

Penrith New Squares

Plans to expand Penrith town centre south into the Southend Road area began by expanding the swimming pool area into a leisure centre, to replace a previous car park and sports fields, including ones used by Penrith and Penrith United football clubs. Plans for the rest of the scheme were drawn up by a property firm and included a supermarket[25] and shopping streets, car parking and housing. Penrith New Squares refers to shops to be centred round two squares for parking and public entertainment.[26]

Work here was suspended in October 2008 due to the financial crisis,[27] but a new deal was agreed with Sainsbury's and it resumed in 2011. The update includes less new housing, with parts deferred for up to five years.[28] Sainsburys opened in December 2011. In June 2013, the first shop in the squares opened, along with a walk through from Sainsburys to the town centre.

Landmarks

The main church is St Andrew's, built in 1720–1722 in an imposing

Ruins of Penrith Castle (14th–16th centuries) can be seen from the adjacent railway station. It is run by English Heritage. To the south-east of the town are more substantial ruins of Brougham Castle, also held by English Heritage, as are the ancient henge sites known as Mayburgh Henge and King Arthur's Round Table to the south.

The town centre has a Clock Tower erected in 1861 to mark Philip Musgrave of Edenhall. Hutton Hall in Friargate has a 14th-century pele tower at the rear, attached to an 18th-century building. Dockray Hall (once the Gloucester Arms) dates from about 1470 and may include remains of another pele tower.[30] Richard, Duke of Gloucester resided there before becoming King Richard III and carried out extensive work at Penrith Castle about 1471.

Penrith has many

.Just north of the town is a wooded signal-beacon hill named Beacon Hill, originally Penrith Fell. Its last use was probably in 1804 in the war against Napoleon. Traditionally, Beacon Pike warned of danger from Scotland. Though ringed by commercial woodland owned by Lowther Estates, it still has natural woodlands visited by locals and tourists. On a clear day most of Eden Valley, local fells, Pennines and parts of the North Lakes can be seen. Beacon Hill possibly gave Penrith its Celtic name of "red hill".

A fibreglass 550 cm (18 ft)-tall statue of King Kong once stood in the Skirsgill Auction Mart.[31]

Transport

Railway

- Avanti West Coast operates inter-city services between London Euston, Glasgow Central and Edinburgh Waverley, with trains calling at Birmingham, Carlisle, Crewe, Lancaster and Preston.[33]

- Manchester Airport and Glasgow Central.[34]

Buses and coaches

Local bus services are operated mostly by

Roads

Penrith is close to junction 40 of the

The town has several

Cycling

The National Cycle Network's major National Route 7 runs through the town and National Route 71 stops just short of its southern edge.

Public services

Health

Penrith Hospital and Health Centre lies along Bridge Lane at the southern entrance to the town, close to the Kemplay Bank roundabout, where the

There are several private and National Health Service dental practices in the town.

Police and fire

Penrith falls comes under Cumbria Constabulary, with headquarters at Carleton Hall on the outskirts of the town. The town's own police station was in Hunter Lane, but has since been replaced by a smaller one close to Carleton Hall. Carleton Hall also houses Penrith's fire station and the headquarters of Cumbria Fire and Rescue Service.

Ambulance

The

Notable people

In order of birth:

- Plantagenetkings.

- The John Loudon Macadam(1756–1836), inventor of macadamized roads, lived for a while at Cockell House in Townhead. Close by are streets named Macadam Way and Macadam Gardens.

- John Littlejohn (1756-1836), an American Methodist preacher and circuit-rider, was born in Penrith.

- Penrith was the home town of the mother of the poet William Wordsworth (1770–1850). He spent some of his childhood there, attending school with Mary Hutchinson, his later wife.

- Douay Bible, served as Catholic priest here from 1839 until his death in 1849.

- The Frances Trollope (1779–1863), Anthony Trollope's mother, lived for a while at a house called Carleton Hill (not Carleton Hall) outside the town on the Alston road.

- MPand social reformer, spent some of his childhood at Page Hall in Foster Street. The houses at Townhead called Plimsoll Close are named after him.

- Percy Toplis (1896–1920), the "monocled mutineer", was shot and killed on the run by police at Plumpton, near Penrith. He is buried in Penrith's Beacon Edge Cemetery in an unmarked grave. His monocle is on display in Penrith and Eden Museum.

- Mary (1916–2018), wife of Prime Minister Harold Wilson, lived in Penrith whilst her father was minister at the Congregational Churchin Duke Street.

- Stuart Lancaster (born 1969) became head coach of the England national rugby union.

- England cricketinternational, was born in Carlisle, but grew up in the Penrith area. Nixon retired from professional sport in 2011.

- Angela Lonsdale (born 1970 in Penrith), actress, is perhaps best known as policewoman Emma Taylor in Coronation Street and currently stars as DI Eva Moore in the BBC soap Doctors.

- Charlie Hunnam (born 1980), the actor, attended Queen Elizabeth Grammar School, Penrith (QEGS) and lived locally in his teenage years. He claimed it is "just about the worst place you could hope to live".[36]

- Lewis Brett Guy (born 1985), former professional footballer.

- 2012 Scottish Cup final against Hibernian.

- Oliver Turvey (born 1987), racing driver, attended Queen Elizabeth Grammar School and lives locally.

- Stephen Hindmarch (born 1989), a professional footballer, was born here.

Night life

Like other rural towns of its size, Penrith relies on

The Lonsdale (formerly the Alhambra) in Middlegate is a cinema with three screens built in 1910 by William Forrester. There was until the 1980s another cinema called the Regent on Old London Road.

Amateur dramatics and musicals are staged at the Penrith Players Theatre, Ullswater Community College and Queen Elizabeth Grammar School.

Penrith dialect

The Penrith dialect known as Penrithian, spoken around the Penrith and Eden district area, is a variant of the Cumbrian dialect.

Media

The local newspaper, the

The Free, monthly circulated Eden Local community magazine http://www.cumbrianlocal.co.uk/ has been posted through doors since 2010 in Penrith and in areas surrounding it in the Eden Valley. It was set up to launch https://www.edenfm.co.uk/ It reaches its 200th publication in 2023

Penrith lies with the

Penrith was used as a setting in the 1940 book Cue for Treason by Geoffrey Trease. It was also a setting for Bruce Robinson's 1987 film Withnail and I, although the Penrith scenes were actually filmed in Stony Stratford, Buckinghamshire.[37]

Education

Uniformed youth organisations

Penrith hosts two Community Cadet Forces units: 1247 Squadron of the Air Training Corps and Penrith Detachment of Cumbria Army Cadet Force.

Primary schools

- Brunswick School (formerly County Infants), Brunswick Road

- Beaconside Primary, Eden Mount/Brent Road. Until 2008 there were separate Beaconside Infant and Junior schools.

- North Lakes School (formerly Wetheriggs Junior; was at first a girls-only school), Huntley Avenue – North Lakes was one of the first schools in England to be awarded a Sing Up Gold Award (in December 2008) and their highest accolade, a Sing Up Platinum Award (likewise in December 2008).

- St Catherines Roman Catholic Primary, Drovers Lane

- Hunter Hall (preparatory school), Frenchfield

Secondary schools

- Ullswater Community College (formerly Ullswater High School, and before that, two single sex secondary modern schools on the same site called Tynefield (girls) and Ullswater (boys)), Wetheriggs Lane

- Queen Elizabeth Grammar School (QEGS) (selective), Ullswater Road

Further education

- The former UCLAN and subsequently the University of Cumbria. Since the closure some facilities remain available for public and educational use,[38] for example the Equestrian Centre re-opened in February 2022[39]

- Ullswater Community College had a large further or adult education centre.

Former schools in the town include:

- Girls National School (building now housing school replaced by Beaconside Juniors), Drovers Lane

- Boys National School or St Andrews School for Boys (building now demolished school replaced by Beaconside Juniors), Benson Row

- National Infants School (now Penrith Playgroup Nursery School), Meeting House Lane

- Robinsons School – this was a girls-only school founded with 29 pupils, which later became a mixed (infant) school founded in 1670 by William Robinson, a local merchant who made good in London. It now houses the town's museum and tourist information centre, Middlegate, and has the following inscription above the door: "Ex sumptibus DN Wil Robinson civis Lond anno 1670 DN"

- County Girls School (building now part of Brunswick Infants, the school was replaced by Wetheriggs), Brunswick Road

- County Boys School (the building now QEGS Sixth Form Centre, also for a while an annexe to Wetheriggs). The school merged with Wetheriggs Girls to form Wetheriggs Junior, Ullswater Road

- Tynefield co-educationalbut later girls only), Wetheriggs Lane

- Ullswater Secondary Modern (boys only), Wetheriggs Lane. Ullswater and Tynefield schools and buildings merged to create Ullswater High in 1980.

Places of worship

Church of England

- Parish, sited in the centre of Penrith. It is the largest of four parishes making up the Penrith Team Ministry.

- Christ Church, Drovers Lane/Stricklandgate, opened in 1850 as a separate parish, but from 1968 to 2008 was part of the United Parish of Penrith. It is now again a separate parish church for the northern part of the town, remaining within the Penrith Team Ministry.

Roman Catholic Church

- St Catherine's, Drovers Lane

Methodist Church of Great Britain

- Penrith Methodist Church, Wordsworth Street

Other churches

- Society of Friends, Quaker Meeting House, Meeting House Lane

- Gospel Hall Evangelical Church, Albert Street/Queen Street

- King's Church Eden - part of the Newfrontiers family of churches

- Oasis Evangelical Church, Brackenber Court, Musgrave Street

- Salvation Army, Hunter Lane

- Church in the Barn, Castietown Community Centre, Gilwilly

- Influence Church Assemblies of God, Burrowgate

- Jehovah's Witnesses, Skirsgill Lane, Eamont Bridge

Mosques

The town also has two places of worship for Islam. It has an Islamic centre called the "Quba Islamic Centre"[40] and a mosque called the "Al-Amin Mosque". Both are close to each other and on both Middlegate and Bluebell Lane.

Economy

As a market town relying heavily on the tourist trade, Penrith benefits from some high-street chain stores and local specialist shops alongside other businesses such as

Market days are traditionally Tuesday and Saturday. On Tuesdays there was a small outdoor market in Great Dockray and Cornmarket. This ceased in the early 21st century, since when a small farmers' market has been held in the Market Square once a month. On Saturdays, Cumbria's largest outdoor market takes place at the Auction Mart alongside the M6 motorway junction 40.

The main central shopping areas are Middlegate, Little Dockray, Devonshire Street/Market Square, Cornmarket, King Street, Angel Lane and the Devonshire Arcade and Angel Square precincts, with some shops in Burrowgate, Brunswick Road and Great Dockray.

Although the main industries are based around tourism and agriculture, some others are represented. For example, in 2011

Agriculture-based industries include

Penrith was known for its

Fylde Guitars is a manufacturer of hand-made fretted musical instruments, founded in Penrith in 1973 by luthier Roger Bucknall. Its instruments command high prices. All are hand-made using traditional techniques and have been developed in collaboration with professional players. Fylde Guitars is the only UK guitar maker to have been awarded the Acoustic Guitar Magazine "Gold Award", in 2000.

Sport

Penrith is home to

Penrith Netball Club has been active in the town since 2002.[41] They cater for junior players from the age of 11, as well as adults, playing at both secondary schools (QEGS and Ullswater Community College) in the town. Penrith Netball are currently playing in the Carlisle Netball League.

Penrith A.F.C. plays in the Northern Football League.

There is a skate park area by the Penrith Leisure Centre. The skate park opened in 2007.[42]

Penrith has a golf club and driving range. Penrith Castle Park houses the town's Bowling Club.

Penrith Swimming Club was founded in 1881 and was then based at Frenchfield in the River Eamont. Training sessions originally involved great variations of conditions that challenged the skills of any swimmer. Icy water, strong currents and obstacles like weed and the odd eel or two provided the ultimate test of stamina. It was all a far cry from conditions for today's training sessions, held at Penrith Leisure Centre.[43]

Penrith Canoe Club, founded in 2012, trains at the local leisure centre. Its main activity is canoe polo, in which the club was represented at the World Championships in Syracuse, Italy 2016 by its under-21 women's squad, which finished a respectable fourth.

Penrith Tennis Club is located in the grounds of Penrith Rugby Club at Carleton Village.

Twin town

Since 1989, Penrith has had a

Regular events

- Mayday Carnival

- On the first Monday in May, Penrith holds a Mayday Carnival run by Penrith Lions Club. It includes a parade, street dancers and fairground rides in the Great Dockray and Market Square car parks of the commercial area. The procession includes floats, vintage cars and tractors, a marching band, various local celebrities and members of the Penrith Lions Club. It starts in the yard of Ullswater Community College and ends in the bus station car park. Many roads in the centre are closed for the event.[45]

- Penrith Agricultural Show

- The first Penrith Show was held in 1834. From 2019 the event takes place on the 3rd Saturday in July.[46]

- The Winter Droving

- Held in late October/early November 'The Winter Droving Festival' celebrates all things rural, traditional and fun. The highlight is a torch-lit procession through the town, featuring fire, lanterns, masquerade and music and mayhem. The event is a celebration of Penrith and its age-old role as the market place for the local area, where for centuries livestock and produce has been brought for sale.[47]

- Kendal Calling

- Music Festival held in late July each year at Lowther Deer Park has had headline acts that included the Manic Street Preachers.[48]

- Potfest

- Ceramic festivals take place as Potfest in the Pens and Potfest in the Park at Skirsgill Auction Mart and Hutton in the Forest.[49]

- Lowther Show

- Held at nearby Prince Philip.[50]

Climate

Like most of the

| Climate data for Newton Rigg, elevation: 169 m (554 ft), 1981–2010 normals, extremes 1906–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 13.9 (57.0) |

14.4 (57.9) |

21.1 (70.0) |

24.6 (76.3) |

27.2 (81.0) |

29.7 (85.5) |

29.5 (85.1) |

31.1 (88.0) |

26.7 (80.1) |

24.4 (75.9) |

17.2 (63.0) |

17.2 (63.0) |

31.1 (88.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 6.1 (43.0) |

6.6 (43.9) |

8.8 (47.8) |

11.6 (52.9) |

15.1 (59.2) |

17.4 (63.3) |

19.5 (67.1) |

19.0 (66.2) |

16.3 (61.3) |

12.5 (54.5) |

8.8 (47.8) |

6.4 (43.5) |

12.4 (54.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 3.4 (38.1) |

3.6 (38.5) |

5.4 (41.7) |

7.4 (45.3) |

10.4 (50.7) |

13.0 (55.4) |

15.1 (59.2) |

14.6 (58.3) |

12.3 (54.1) |

9.1 (48.4) |

5.9 (42.6) |

3.4 (38.1) |

8.6 (47.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 0.6 (33.1) |

0.6 (33.1) |

2.0 (35.6) |

3.2 (37.8) |

5.7 (42.3) |

8.6 (47.5) |

10.7 (51.3) |

10.2 (50.4) |

8.2 (46.8) |

5.7 (42.3) |

2.9 (37.2) |

0.4 (32.7) |

4.9 (40.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −16.7 (1.9) |

−20.0 (−4.0) |

−13.9 (7.0) |

−15.0 (5.0) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

1.1 (34.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

−6.7 (19.9) |

−12.6 (9.3) |

−17.7 (0.1) |

−20.0 (−4.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 101.5 (4.00) |

74.3 (2.93) |

75.8 (2.98) |

52.2 (2.06) |

56.1 (2.21) |

58.6 (2.31) |

70.2 (2.76) |

70.1 (2.76) |

76.3 (3.00) |

106.9 (4.21) |

100.1 (3.94) |

105.0 (4.13) |

947.0 (37.28) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 15.1 | 11.2 | 13.1 | 10.8 | 10.6 | 10.4 | 11.1 | 11.5 | 11.6 | 15.3 | 15.3 | 14.4 | 150.4 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 38.8 | 59.0 | 97.0 | 135.4 | 166.9 | 161.7 | 160.1 | 145.5 | 114.6 | 79.4 | 41.7 | 37.2 | 1,237.3 |

| Source 1: Met Office[55] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: KNMI[56] Meteo Climat[57] | |||||||||||||

See also

- Listed buildings in Penrith, Cumbria

- Cockermouth, Keswick and Penrith Railway

- Penrith and The Border (UK Parliament constituency)

- Penrith Mountain Rescue Team

- Penrith Hoard

References

- ^ "Penrith". City population. Retrieved 25 October 2022.

- Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ Ekwall, E (1947). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place Names. Oxford, UK: OUP. p. 345.

- ISBN 0-19-852758-6.

- ISBN 0904889726.

- ^ Williamson, W. A. (1849). Local Etymology; or names of places in the British Isles, and in other parts of the world. p. 92.

- ISBN 0-905404-70-X.

- ^ Tino Oudesluijs (2020). "Revisiting some problematic British-Celtic place names in Northwest England". in "Kelten. Mededelingen van de Stichting A. G. van Hamel voor Keltische Studies".

- ^ Higham and Jones (1985), p. 10.

- ^ Higham and Jones (1985), p. 66.

- ^ Roman Britain. "Voreda". Archived 8 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Cumbria SMR no. 11055: Site of Roman road.

- ^ R. G. Collingwood and I. Richmond, The Archaeology of Roman Britain London, Methuen, 1969.

- ^ "Viking Archaeology: Treasure found in Cumbria". 13 September 2007. Archived from the original on 2 June 2008.

- ^ Newman (2014), p. 47.

- ^ Stringer (2019), pp. 73–84.

- ^ Gilpin, William (1786), Observations relative chiefly to Picturesque Beauty, Made in the year 1772.... Cumberland & Westmoreland. R. Blamire, London. Facing p. 85.

- ^ Colman (2003), pp. [237]–258.

- ^ "Penrith Town Council".

- Oxford Archaeology North.

- ^ Under the ALFA (Adaptive Land Use for Flood Alleviation) scheme: Eden Archived 22 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine, ALFA

- ^ "Thacka Beck". Archived from the original on 29 December 2013. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- ^ Historic England. "Carleton Hall (Cumbria Police Headquarters) (1312133)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ France, Ben; Jackson, Liam (18 September 2015). "Ambleside United Sink The Pinks". Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ "Council rejects Tesco's millions in Penrith supermarket deal". Cumberland and Westmorland Herald. 29 December 2001. Archived from the original on 12 November 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ "New Homes in Penrith - Living at Penrith New Squares". Archived from the original on 21 November 2008.

- ^ Cumberland News 10 October 2008 Archived 13 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Eden District Council Press Releases Archived 9 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "PENRITH, Cumberland-Church history". GENUK. Retrieved 9 December 2010.

- ^ Historic England. "Dockray Hall (12326)". Research records (formerly PastScape). Retrieved 4 June 2011.

- Cumberland News. 28 January 2011. Archived from the originalon 24 March 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- ^ Services calling at Penrith North Lakes on 3 January 2024 Realtime Trains

- ^ "Our latest timetables and ticket info". Avanti West Coast. May 2023. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

- ^ "Timetables". TransPennine Express. 21 May 2023. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

- ^ a b "Penrith Bus Services". Bus Times. 2023. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

- ^ "Actor claims Penrith is "just about worst place you could hope to live"". cwherald.com. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ Scovell, Adam (11 April 2017). "In search of the Withnail & I locations 30 years on". British Film Institute. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- ^ "Newton Rigg's new owners show their hand". Cumberland and Westmorland Herald. 10 November 2021.

- ^ "Re-opening of Newton Rigg's equestrian centre is pivotal moment for Cumbria". Newton Rigg Ltd. 2 February 2022. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ "Mosque Map". mosques.muslimsinbritain.org. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ^ "Penrith Netball Club". Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ^ "Penrith Skate Park". Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- ^ "Penrith Swimming Club". penrithswimmingclub.co.uk. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- ^ Sister city arrangements for Penrith Archived 12 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Photographs etc. Retrieved 26 August 2021.

- ^ "Downpours didn't dampen spirits at Penrith Show". News and Star. 22 July 2017.

- ^ Irving, Jonny (28 October 2017). "Winter Droving set to bring colourful end to Cumbria's summer". News and Star.

- ^ Binns, Simon (31 July 2017). "Kendal Calling 2017 in pictures – Stereophonics, Tinie Tempah, Editors, Manic Street Preachers and more". Manchester Evening News.

- ^ "Potfest in Penrith celebrates 25th anniversary". Great British Life. 20 June 2019.

- ^ "Lowther Show given royal seal of approval by Prince Philip". News and Star. 11 August 2014. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017.

- ^ "1900 record". Trevor Harley. April 2020.

- KNMI.

- UKMO.

- UKMO. Archived from the originalon 6 February 2012.

- ^ "Newton Rigg 1981–2010 averages". Met Office. Archived from the original on 31 October 2012. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- KNMI. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- KNMI. Retrieved 23 November 2020.

Mullett references

- ^ Mullett (2017a), p. 5.

- ^ Mullett (2017a), p. 5.

- ^ Mullett (2017a), pp. 7–12.

- ^ Mullett (2017a), p. 3.

- ^ Mullett (2017a), pp. 10–12.

- ^ Mullett (2017a), pp. 14–15.

- ^ Mullett (2017a), pp. 16–17.

- ^ Mullett (2017a), p. 32.

- ^ Mullett (2017a), pp. 29–31.

- ^ Mullett (2017a), pp. 33–34.

- ^ Mullett (2017a), p. 35.

- ^ Mullett (2017a), pp. 37–39.

- ^ Mullett (2017a), p. 40.

- ^ Mullett (2017a), pp. 44–55.

- ^ Mullett (2017a), pp. 56–63.

- ^ Mullett (2017a), pp. 64–65.

- ^ Mullett (2017a), pp. 66–76.

- ^ Mullett (2017a), pp. 66–88.

- ^ Mullett (2017a), pp. 90–97.

- ^ Mullett (2017a), pp. 93–105.

- ^ Mullett (2017a), pp. 106–126.

- ^ Mullett (2017b), pp. 7–11.

- ^ Mullett (2017b), pp. 15–21.

- ^ Mullett (2017b), pp. 26–35.

- ^ Mullett (2017b), pp. 41–98.

- ^ Mullett (2017b), pp. 99–125.

- ^ Mullett (2018), pp. 5–18.

- ^ Mullett (2018), pp. 25–31.

- ^ Mullett (2018), pp. 32–41.

- ^ Mullett (2018), pp. 67–76.

- ^ Mullett (2018), pp. 101–102.

- ^ Mullett (2018), pp. 83-96.

- ^ Mullett (2018), pp. 103–104.

Sources

- Colman, Clark Stuart (2003). "The Glorious Revolution of 1688 in Cumberland and Westmorland: "the merit of this action"". Northern History. 40 (2): [237]–258. S2CID 155007993.

- Ewanion (1993). History of Penrith : from the earliest record to the present time (Reprint of 1894 ed.). Carlisle: Bookcase. pp. vii, 376. ISBN 0-9519920-3-1..

- Higham, N.J.; Jones, G.D.B. (1985). The Carvetii. Peoples of Roman Britain. Stroud: Alan Sutton. pp. xiii, 1–158. ISBN 978-0862990886.

- Mullett, Michael A. (2017a). A New history of Penrith: book I: from pre-history to the close of the Middle Ages. Carlisle: Bookcase. pp. iv, 172 pp. ISBN 9781901414998.

- Mullett, Michael A. (2017b). A New history of Penrith: book II: Penrith under the Tudors. Carlisle: Bookcase. pp. 1–164. ISBN 9781912181049.

- Mullett, Michael A. (2018). A New history of Penrith: book III: Penrith in the Stuart century, 1603–1714. Carlisle: Bookcase. pp. 1–193. ISBN 9781912181100.

- Mullett, Michael A. (2019). A New history of Penrith: book IV: Penrith in the eighteenth century, 1715-1800. Carlisle: Bookcase. pp. 1–297. ISBN 9781912181209.

- Mullett, Michael A. (2020). A New history of Penrith: book V: Penrith in the nineteenth century, 1800-1901: chapters on the Victorian town. Carlisle: Bookcase. pp. 1–402. ISBN 9781912181346.

- Mullett, Michael A. (2022). A New history of Penrith: book VI: Penrith in the twentieth century, 1900-1974: essays on the public realm. Carlisle: Bookcase. pp. 1–346. ISBN 9781912181520.

- Newman, Rachel (2014). "Shedding light on the 'Dark Ages' in Cumbria : through a glass darkly". In Keith J. Stringer (ed.). North-West England from the Romans to the Tudors : essays in memory of John Macnair Todd. Extra Series. Vol. XLI. Carlisle: Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society. pp. xviii, 288, pp. [29]–60. ISBN 9781873124659.

- Stringer, Keith J. (2019). The Kings of Scots, the liberty of Penrith, and the making of Britain (1237-1296). Tract series no.28. Kendal: Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society. ISBN 9781873124802.

External links

- Cumbria County History Trust: Penrith (nb: provisional research only - see Talk page)

- Penrith Leisure Centre

- Area profile based on 2001 census Details