Patera

In the

Although the two terms may be used interchangeably, particularly in the context of

Use

Libation was a central and vital aspect of

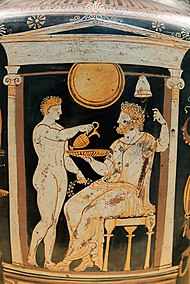

The form of libation called spondē is typically the ritualized pouring of wine from a jug or bowl held in the hand. The most common ritual was to pour the liquid from an oinochoē (wine jug) into a phiale.[8] Libation generally accompanied prayer.[9] The Greeks stood when they prayed, either with their arms uplifted, or in the act of libation with the right arm extended to hold the phiale.[10] After the wine offering was poured from the phiale, the remainder of the contents was drunk by the celebrant.[11]

In Roman art, the libation is shown performed at an altar, mensa (sacrificial meal table), or tripod. It was the simplest form of sacrifice, and could be a sufficient offering by itself.[12] The introductory rite (praefatio) to an animal sacrifice included an incense and wine libation onto a burning altar.[13] Both emperors and divinities are frequently depicted, especially on coins, pouring libations from a patera.[14] Scenes of libation and the patera itself commonly signify the quality of pietas, religious duty or reverence.[15]

-

kylix, c. 460 BC)

-

Etruscan priest with phiale (2nd century BC)

-

Silver patera fromRoman Spain), 2nd–1st century BC)

-

Patera with Marcus Aurelius (Georgia, 2nd century AD)

-

Roman priest,capite velato(2nd–3rd century AD)

Architecture

In architecture, oval features on plaster friezes on buildings may be called paterae (plural).[18][19]

See also

- Parabiago patera, which is actually a platter or plate

References

- ^ Simon Janashia Museum of Georgia 122.jpg

- ^ There is no meaningful distinction between the two terms: Nancy Thompson de Grummond and Erika Simon, The Religion of the Etruscans (University of Texas Press, 2006), p. 171; Gocha R. Tsetskhladze, North Pontic Archaeology: Recent Discoveries and Studies (Brill, 2001), p. 239; Rabun Taylor, The Moral Mirror of Roman Art (Cambridge University Press, 2008), p. 104, 269; Rebecca Miller Ammerma, The Sanctuary of Santa Venera at Paestum (University of Michigan Press, 2002), pp. 64, 66.

- ^ Patera is not to be confused with the Greek (Πατέρας) Patéras or Father.

- ^ Louise Bruit Zaidman and Pauline Schmitt Pantel, Religion in the Ancient Greek City, translated by Paul Cartledge (Cambridge University Press, 1992, 2002, originally published 1989 in French), p. 28.

- ^ Walter Burkert, Greek Religion (Harvard University Press, 1985, originally published 1977 in German), pp. 70, 73.

- ^ Hesiod, Works and Days 724–726; Zaidman and Pantel, Religion in the Ancient Greek City, p. 39.

- ^ Zaidman and Pantel, Religion in the Ancient Greek City, p. 40; Burkert, Greek Religion, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Zaidman and Pantel, Religion in the Ancient Greek City, p. 40.

- ^ Burkert, Greek Religion, pp. 70–71.

- ^ William D. Furley, "Prayers and Hymns," in A Companion to Greek Religion (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010), p. 127; Jan N. Bremmer, "Greek Normative Animal Sacrifice," p. 138 in the same volume.

- ^ Zaidman and Pantel, Religion in the Ancient Greek City, p. 40.

- ^ Katja Moede, "Reliefs, Public and Private," in A Companion to Roman Religion (Blackwell, 2007), pp. 165, 168.

- ^ Moede, "Reliefs, Public and Private," pp. 165, 168; Nicole Belayche, "Religious Actors in Daily Life: Practices and Related Beliefs," in A Companion to Roman Religion, p. 280.

- ^ Jonathan Williams, "Religion and Roman Coins," in A Companion to Roman Religion, pp. 153–154.

- ^ John Scheid, "Sacrifices for Gods and Ancestors," in A Companion to Roman Religion, p. 265.

- ^ "Gold phiale (libation bowl)," Metropolitan Museum of Art, accession no. 62.11.1

- ^ British Museum Collection)

- ^ "22, North Street, Ashford, Kent".

- ^ Calder Loth (2010-10-05). "Classical comments: the patera". Institute of Classical Architecture & Art. Archived from the original on 2011-08-10.

![Gold phiale with repoussé bees, acorns, and beechnuts and Greek and Punic inscription (4th–3rd century BC, Met)[16]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7a/Met%2C_greek%2C_gold_phiale%2C_4-3rd_cventury_BC_01.JPG/198px-Met%2C_greek%2C_gold_phiale%2C_4-3rd_cventury_BC_01.JPG)

![Silver patera from Syria with figures from the founding of Rome (2nd century AD, British Museum[17]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b7/Ancient_syro-romanian_silver_Patera.jpg/150px-Ancient_syro-romanian_silver_Patera.jpg)