Philip Zimbardo

Philip Zimbardo | |

|---|---|

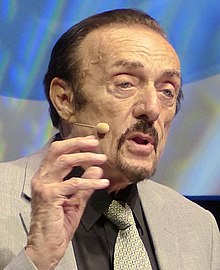

Zimbardo in 2017 | |

| Born | Philip George Zimbardo March 23, 1933 New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Brooklyn College (BA) Yale University (MS, PhD) |

| Known for | Stanford prison experiment The Time paradox The Lucifer Effect Abu Ghraib prison analysis time perspective therapy social intensity syndrome |

| Spouses |

|

| Signature | |

Philip George Zimbardo (

Early life

Zimbardo was born in New York City on March 23, 1933, to a family of Italian immigrants from Cammarata in Sicily. Early in life he experienced discrimination and prejudice, growing up poor on welfare in the South Bronx,[3] and being Italian. He was often mistaken for other races and ethnicities such as Jewish, Puerto Rican or black. Zimbardo has said these experiences early in life triggered his curiosity about people's behavior, and later influenced his research in school.[4]

He completed his B.A. with a triple major in

He taught at Yale from 1959 to 1960. From 1960 to 1967, he was a professor of psychology at New York University College of Arts & Science. From 1967 to 1968, he taught at Columbia University. He joined the faculty at Stanford University in 1968.[8]

Stanford prison study

Background

In 1971, Zimbardo accepted a tenured position as professor of psychology at Stanford University. With a government grant from the

Zimbardo's primary reason for conducting the experiment was to focus on the power of roles, rules, symbols, group identity and situational validation of behavior that generally would repulse ordinary individuals. "I had been conducting research for some years on deindividuation, vandalism and dehumanization that illustrated the ease with which ordinary people could be led to engage in anti-social acts by putting them in situations where they felt anonymous, or they could perceive of others in ways that made them less than human, as enemies or objects," Zimbardo told the Toronto symposium in the summer of 1996.[11]

Experiment

Zimbardo himself took part in the study, playing the role of "prison superintendent" who could mediate disputes between guards and prisoners. He instructed guards to find ways to dominate the prisoners, not with physical violence, but with other tactics, verging on torture, such as sleep deprivation and punishment with solitary confinement. Later in the experiment, as some guards became more aggressive, taking away prisoners' cots (so that they had to sleep on the floor), and forcing them to use buckets kept in their cells as toilets, and then refusing permission to empty the buckets, neither the other guards nor Zimbardo himself intervened. Knowing that their actions were observed but not rebuked, guards considered that they had implicit approval for such actions.[12]

In later interviews, several guards told interviewers that they knew what Zimbardo wanted to have happen, and they did their best to make that happen.[13] Less than two full days into the study, one inmate pretended to suffer from depression, uncontrolled rage and other mental dysfunctions. The prisoner was eventually released after screaming and acting in an unstable manner in front of the other inmates. He later revealed that he faked this "breakdown" to get out of the study early to focus on school. This prisoner was replaced with one of the alternates.[9]

Results

By the end of the study, the guards had won complete control over all of their prisoners and were using their authority to its greatest extent. One prisoner had even gone as far as to go on a hunger strike. When he refused to eat, the guards put him into solitary confinement for three hours (even though their own rules stated the limit that a prisoner could be in solitary confinement was only one hour). Instead of the other prisoners looking at this inmate as a hero and following along in his strike, they chanted together that he was a bad prisoner and a troublemaker. Prisoners and guards had rapidly adapted to their roles, stepping beyond the boundaries of what had been predicted and leading to dangerous and psychologically damaging situations. Zimbardo himself started to give in to the roles of the situation. He had to be shown the reality of the study by Christina Maslach, his girlfriend and future wife, who had just received her doctorate in psychology.[14] Zimbardo reflects that the message from the study is that "situations can have a more powerful influence over our behaviour than most people appreciate, and few people recognize [that]."[15]

At the end of the study, after all the prisoners had been released and the guards let go, everyone was brought back into the same room for evaluation and to be able to get their feelings out in the open towards one another. Ethical concerns surrounding the study often draw comparisons to the Milgram experiment, which was conducted in 1961 at Yale University by Stanley Milgram, Zimbardo's former high school friend.[16] Zimbardo and Maslach married in 1972, a year after the study.[17]

More recently, Thibault Le Texier of the University of Nice has examined the archives of the experiment, including videos, recordings, and Zimbardo's handwritten notes, and argued that "The guards knew what results the experiment was supposed to produce ... Far from reacting spontaneously to this pathogenic social environment, the guards were given clear instructions for how to create it ... The experimenters intervened directly in the experiment, either to give precise instructions, to recall the purposes of the experiment, or to set a general direction ...In order to get their full participation, Zimbardo intended to make the guards believe that they were his research assistants.".[18] Since his original publication in French,[19] Le Texier's accusations have been taken up by science communicators in the United States.[20] In his book Humankind - a hopeful history (2020)[21][22] historian Rutger Bregman points out the charge that the whole experiment was faked and fraudulent; Bregman argued this experiment is often used as an example to show people easily succumb to evil behavior, but Zimbardo has been less than candid about the fact that he told the guards to act the way they did. More recently, an APA psychology article reviewed this work in detail [23] and concluded that Zimbardo encouraged the guards to act the way they did, so rather than this behavior appearing on its own, it was generated by Zimbardo.

Prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib Prison

Zimbardo reflects on the dramatic visual similarities between the behavior of the participants in the Stanford prison experiment, and the prisoner abuse at Abu Ghraib. He did not accept the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Myers', claim that the events were due to a few rogue soldiers and that it did not reflect on the military. Instead he looked at the situation the soldiers were in and considered the possibility that this situation might have induced the behavior that they displayed. He began with the assumption that the abusers were not "bad apples" and were in a situation like that of the Stanford prison study, where physically and psychologically healthy people were behaving sadistically and brutalizing prisoners.[15] Zimbardo became absorbed in trying to understand who these people were, asking the question "are they inexplicable, can we not understand them". This led him to write the book The Lucifer Effect.[15]

The Lucifer Effect

The Lucifer Effect was written in response to his findings in the Stanford Prison Experiment. Zimbardo believes that personality characteristics could play a role in how violent or submissive actions are manifested. In the book, Zimbardo says that humans cannot be defined as good or evil because we have the ability to act as both especially at the hand of the situation. Examples include the events that occurred at the

- Mindlessly taking the first small step

- Dehumanization of others

- De-individuation of self (anonymity)

- Diffusion of personal responsibility

- Blind obedience to authority

- Uncritical conformity to group norms

- Passive tolerance of evil through inaction or indifference

Time

In 2008, Zimbardo published his work with John Boyd about the Time Perspective Theory and the Zimbardo Time Perspective Inventory (ZTPI) in The Time Paradox: The New Psychology of Time That Will Change Your Life. In 2009, he met Richard Sword and started collaborating to turn the Time Perspective Theory into a clinical therapy, beginning a four-year long pilot study and establishing time perspective therapy.[27] In 2009, Zimbardo did his Ted Talk "The Psychology of Time" about the Time Perspective Theory. According to this Ted Talk, there are six kinds of different Time Perspectives which are Past Positive TP (Time Perspective), Past Negative TP, Present Hedonism TP, Present Fatalism TP, Future Life Goal-Oriented TP and Future Transcendental TP.[28] In 2012, Zimbardo, Richard Sword, and his wife Rosemary authored a book called The Time Cure.[29] Time Perspective therapy bears similarities to Pause Button Therapy, developed by psychotherapist Martin Shirran, whom Zimbardo corresponded with and met at the first International Time Perspective Conference at the University of Coimbra, Portugal. Zimbardo wrote the foreword to the second edition of Shirran's book on the subject.[30]

Heroic Imagination Project

As of 2014 Zimbardo is heading a movement for everyday heroism as the founder and director of the Heroic Imagination Project (HIP), a non-profit organization dedicated to promoting heroism in everyday life.[1] The project is currently collecting data from former American gang members and individuals with former ties to terrorism for comparison, in an attempt to better understand how individuals change violent behavior. This research portion of the project is co-headed by Rony Berger, Yotam Heineburg, and Leonard Beckum.[31] He published an article contrasting heroism and altruism in 2011 with Zeno Franco and Kathy Blau in the Review of General Psychology.[32]

Social intensity syndrome (SIS)

In 2008, Zimbardo began working with Sarah Brunskill and Anthony Ferreras on a new theory called the social intensity syndrome (SIS). SIS is a new term coined to describe and normalize the effects military culture has on the socialization of both active soldiers and veterans. Zimbardo and Brunskill presented the new theory and a preliminary factor analysis of it accompanying survey at the Western Psychological Association in 2013.[33] Brunskill finished the data collection in December 2013. Through an exploratory component factor analysis, confirmatory factor analysis, internal consistency and validity tests demonstrated that SIS was a reliable and valid construct of measuring military socialization.[34]

Other endeavors

After the prison experiment, Zimbardo decided to look for ways he could use psychology to help people; this led to the founding of

Zimbardo is the co-author of an introductory Psychology textbook entitled Psychology and Life, which is used in many American undergraduate psychology courses. He also hosted a PBS TV series titled Discovering Psychology which is used in many college telecourses.[36]

In 2004, Zimbardo testified for the defense in the

Zimbardo's writing appeared in Greater Good Magazine, published by the Greater Good Science Center of the University of California, Berkeley. Zimbardo's contributions include the interpretation of scientific research into the roots of compassion, altruism, and peaceful human relationships. His most recent article with Greater Good magazine is entitled: "The Banality of Heroism",[38] which examines how ordinary people can become everyday heroes. In February 2010, Zimbardo was a guest presenter at the Science of a Meaningful Life seminar: Goodness, Evil, and Everyday Heroism, along with Greater Good Science Center Executive Director Dacher Keltner.

Zimbardo, who officially retired in 2003, gave his final "Exploring Human Nature" lecture on March 7, 2007, on the

Zimbardo has made appearances on American TV, such as

Zimbardo serves as advisor to the anti-bullying organization Bystander Revolution and appears in the organization's videos to explain the bystander effect[43] and discuss the evil of inaction.[44]

Since 2003, Zimbardo has been active in charitable and economic work in rural Sicily through the Zimbardo-Luczo Fund with

In 2015, Zimbardo co-authored a book "Man (Dis)connected: How Technology Has Sabotaged What It Means To Be Male", which collected research to support a thesis that males are increasingly disconnected from society.[46] He argues that a lack of two-parent households and female-oriented schooling have made it more attractive to live virtually, risking video game addiction or pornography addiction.

Recognition

In 2012, Zimbardo received the

Works

- Influencing attitude and changing behavior: A basic introduction to relevant methodology, theory, and applications (Topics in social psychology), Addison Wesley, 1969

- The Cognitive Control of Motivation. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman, 1969

- Stanford prison experiment: A simulation study of the psychology of imprisonment, Philip G. Zimbardo, Inc., 1972

- Influencing Attitudes and Changing Behavior. Reading, MA: Addison Wesley Publishing Co., 1969, ISBN 0-07-554809-7

- Canvassing for Peace: A Manual for Volunteers. Ann Arbor, MI: Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues, 1970, ISBN

- Influencing Attitudes and Changing Behavior (2nd ed.). Reading, MA: Addison Wesley., 1977, ISBN

- Psychology and You, with David Dempsey (1978).

- Shyness: What It Is, What to Do About It, Addison Wesley, 1990, ISBN 0-201-55018-0

- The Psychology of Attitude Change and Social Influence. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1991, ISBN 0-87722-852-3

- Psychology (3rd Edition), Reading, MA: Addison Wesley Publishing Co., 1999, ISBN 0-321-03432-5

- The Shy Child : Overcoming and Preventing Shyness from Infancy to Adulthood, Malor Books, 1999, ISBN 1-883536-21-9

- Violence Workers: Police Torturers and Murderers Reconstruct Brazilian Atrocities. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2002, ISBN 0-520-23447-2

- Psychology - Core Concepts, 5/e, Allyn & Bacon Publishing, 2005, ISBN 0-205-47445-4

- Psychology And Life, 17/e, Allyn & Bacon Publishing, 2005, ISBN 0-205-41799-X

- The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil, ISBN 1-4000-6411-2

- The Time Paradox: The New Psychology of Time That Will Change Your Life, ISBN 1-4165-4198-5

- The Journey from the Bronx to Stanford to Abu Ghraib, pp. 85–104 in "Journeys in Social Psychology: Looking Back to Inspire the Future", edited by Robert Levine, et al., CRC Press, 2008. ISBN 0-8058-6134-3

- Salvatore Cianciabella (prefazione di Philip Zimbardo, nota introduttiva di Liliana De Curtis). Siamo uomini e caporali. Psicologia della dis-obbedienza. Franco Angeli, 2014.

- Maschi in difficoltà, Zimbardo, Philip, Coulombe, Nikita D., Cianciabella, Salvatore (a cura di), FrancoAngeli Editore, 2017.

- Man (Dis)connected, Zimbardo, Philip, Coulombe, Nikita D., Rider/ ISBN 978-1846044847

- Man Interrupted: Why Young Men are Struggling & What We Can Do About It. Philip Zimbardo, Nikita Coulombe; Conari Press, 2016.[51]

See also

- Human experimentation in the United States

- List of social psychologists

- Banality of evil

References

- ^ a b Tugend, Alina (January 10, 2014). "In Life and Business, Learning to Be Ethical". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 20, 2014. Retrieved January 21, 2014.

- ^ "Phil Zimbardo, Ph.D." Heroic Imagination Project. Archived from the original on February 21, 2014.

- ^ Slavich, George M. (2009). "On 50 years of giving psychology away: An interview with Philip Zimbardo". American Psychological Association. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ^ "Emperor of the Edge". Psychology Today. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ^ "Phil Zimbardo Remembers". Neal Miller. April 15, 1954. Archived from the original on October 8, 2011. Retrieved November 7, 2011.

- ^ Reginald, Robert (2009) [1974]. Contemporary Science Fiction Authors. Wildside Press. p. 297.

- ^ "Mrs. Zimbardo Has Son". The New York Times. November 14, 1962. p. 46.

- ^ "Philip G. Zimbardo". Stanford Prison Experiment – Spotlight at Stanford. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- ^ a b "The Stanford Prison Experiment". Archived from the original on October 7, 2014. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

- ^ "Slideshow on official site". Prisonexp.org. p. Slide 4. Archived from the original on May 12, 2000.

- ^ "The Stanford Prison Experiment: Still powerful after all these years (1/97)". News.stanford.edu. August 12, 1996. Archived from the original on November 18, 2011. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

In the prison-conscious autumn of 1971, when George Jackson was killed at San Quentin and Attica erupted in even more deadly rebellion and retribution, the Stanford Prison Experiment made news in a big way. It offered the world a videotaped demonstration of how ordinary people, middle-class college students, can do things they would have never believed they were capable of doing. It seemed to say, as Hannah Arendt said of Adolf Eichmann, that normal people can take ghastly actions.

- ^ Konnikova, Konnikova (June 12, 2015). "The Real Lesson of the Stanford Prison Experiment". New Yorker. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

Occasionally, disputes between prisoner and guards got out of hand, violating an explicit injunction against physical force that both prisoners and guards had read prior to enrolling in the study. When the "superintendent" and "warden" overlooked these incidents, the message to the guards was clear: all is well; keep going as you are. The participants knew that an audience was watching, and so a lack of feedback could be read as tacit approval. And the sense of being watched may also have encouraged them to perform.

- ^ Ratnasar, Romesh (2011). "The Menace Within". Stanford Alumni Magazine. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

I felt that throughout the experiment, he knew what he wanted and then tried to shape the experiment—by how it was constructed, and how it played out—to fit the conclusion that he had already worked out. He wanted to be able to say that college students, people from middle-class backgrounds—people will turn on each other just because they're given a role and given power.

- ^ "The Stanford Prison Experiment: Still powerful after all these years (1/97)". News.stanford.edu. August 12, 1996. Archived from the original on August 2, 2011. Retrieved November 7, 2011.

- ^ Skeptic Magazine. Archivedfrom the original on April 22, 2012.

- ^ "Emperor of the Edge". Psychology Today. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- ^ Ratnesar, Romesh. "The Menace Within". Stanford Magazine. No. July/August 2011. Stanford, California: Stanford University. Archived from the original on November 10, 2018.

- ^ Thibault Le Texier, "Debunking the Stanford Prison Experiment." American Psychologist, Vol 74(7), Oct 2019, 823-839dx.doi.org/10.1037/amp0000401

- ^ Le Texier, T. (2018). Histoire d’un mensonge: Enquête sur l’expérience de Stanford [History of a Lie: An Inquiry Into the Stanford Prison Experiment]. Paris, France: La Découverte

- ^ Blum, Ben (September 6, 2019). "The Lifespan of a Lie". GEN. Retrieved January 20, 2023.

- ISBN 9780316418539.

- ^ Jennifer Bort Yacovissi (July 16, 2020). "Humankind: A Hopeful History". Washington Independent Review of Books. Retrieved January 5, 2021.

- S2CID 199436917.

- ^ "Panel blames Bush officials for detainee abuse". msnbc.com. December 11, 2008. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- ^ "The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil". The Journal of the American Medical Association. 298 (11): 1338–1340. September 19, 2007.

- ^ The psychology of evil | "Philip Zimbardo: The psychology of evil - YouTube". YouTube. Archived from the original on November 15, 2015. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- S2CID 54843165.

- ^ Zimbardo, Philip (June 22, 2009). "The psychology of time". www.ted.com. Archived from the original on May 4, 2016. Retrieved April 21, 2016.

- ISBN 978-1118205679.

- ISBN 978-1781800485.

- ^ "Heroic Imagination Project - Creating a Society of Heroes in Waiting". Heroicimagination.ning.com. Archived from the original on April 25, 2012. Retrieved December 3, 2011.

- ^ Franco, Z., Blau, K. & Zimbardo, P. (2011). Heroism: A conceptual analysis and differentiation between heroic action and altruism. Review of General Psychology, 5(2), 99-113.

- ^ Brunskill, Sarah; Zimbardo, Philip (April 2013). "Social intensity syndrome phenomenon theory: Looking at the military as a sub culture". Western Psychological Association, Reno, NV. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015.

- .

- ^ What messages are behind today's cults? Archived May 2, 1998, at the Wayback Machine, APA Monitor, May 1997

- ^ "Resource: Discovering Psychology: Updated Edition". Learner.org. Archived from the original on January 11, 2012. Retrieved November 7, 2011.

- ^ James Bone Rome. "The Times | UK News, World News and Opinion". Entertainment.timesonline.co.uk. Archived from the original on August 9, 2011. Retrieved November 7, 2011.

- ^ Franco, Z. & Zimbardo, P. (2006-2007) The banality of heroism Archived June 18, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Greater Good, 3 (2), 30-35

- ^ "Peninsula news | The Mercury News and Palo Alto Daily News". Archived from the original on May 10, 2007.

- ^ "Philip Zimbardo - The Daily Show with Jon Stewart - Video Clip | Comedy Central". Thedailyshow.com. March 29, 2007. Archived from the original on August 11, 2011. Retrieved November 7, 2011.

- ^ "Philip Zimbardo on the Colbert Report". Thesituationist.wordpress.com. February 12, 2008. Archived from the original on September 30, 2011. Retrieved November 7, 2011.

- ^ "Shows - When Good People Do Bad Things". Dr. Phil.com. December 22, 2010. Archived from the original on October 29, 2011. Retrieved November 7, 2011.

- ^ "Bystander Revolution". www.bystanderrevolution.org. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved May 5, 2018.

- ^ "Bystander Revolution". www.bystanderrevolution.org. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved May 5, 2018.

- ^ "Zimbardo's foundation gives hope to Sicilian students". July 24, 2009. Archived from the original on June 11, 2016. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- TheGuardian.com. May 9, 2015. Retrieved October 29, 2018.

- ^ "Award: Phil Zimbardo to receive the APA's Gold Medal Award". Stanford University Psychology Department. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved July 27, 2012.

- ^ Strefa Psyche Uniwersytetu SWPS (June 10, 2011), Tytuł Doktora Honoris Causa dla prof. Zimbardo w SWPS Warszawa, archived from the original on May 5, 2018, retrieved March 2, 2018

- ^ Abrahams, Marc (April 20, 2005). "A simple choice". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Limited. Archived from the original on September 18, 2014. Retrieved October 24, 2014.

- S2CID 45115966.

- ISBN 978-1-57324-689-7.

External links

- Zimbardo's official website

- The Heroic Imagination Project

- Philip G. Zimbardo Papers (Stanford University Archives)

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Philip Zimbardo at TED

- Philip Zimbardo at IMDb

- Philip Zimbardo on the Lucifer Effect, in two parts

- "Critical Situations: The Evolution of a Situational Psychologist - A Conversation with Philip Zimbardo" Archived June 3, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Ideas Roadshow, 2016