Phoenician alphabet

| Phoenician script | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | |

Time period | c. 1050–150 BC Proto-Sinaitic

|

Child systems |

|

Sister systems | |

| ISO 15924 | |

Unicode range | U+10900–U+1091F |

| History of the alphabet | ||

|---|---|---|

|

||

|

||

The Phoenician alphabet

The Phoenician alphabet was used to write

The Phoenician alphabet proper uses 22

History

Origin

The earliest known alphabetic (or "proto-alphabetic") inscriptions are the so-called

The Phoenician alphabet is a direct continuation of the "Proto-Canaanite" script of the

Spread and adaptations

Beginning in the 9th century BC, adaptations of the Phoenician alphabet thrived, including

Another reason for its success was the

The alphabet had long-term effects on the social structures of the civilizations that came in contact with it. Its simplicity not only allowed its easy adaptation to multiple languages, but it also allowed the common people to learn how to write. This upset the long-standing status of literacy as an exclusive achievement of royal and religious elites,

According to Herodotus,[15] the Phoenician prince Cadmus was accredited with the introduction of the Phoenician alphabet—phoinikeia grammata, "Phoenician letters"—to the Greeks, who adapted it to form their Greek alphabet. Herodotus claims that the Greeks did not know of the Phoenician alphabet before Cadmus. He estimates that Cadmus lived sixteen hundred years before his time (while the historical adoption of the alphabet by the Greeks was barely 350 years before Herodotus).[16]

The Phoenician alphabet was known to the Jewish sages of the Second Temple era, who called it the "Old Hebrew" (Paleo-Hebrew) script.[17][clarification needed]

Notable inscriptions

The conventional date of 1050 BC for the emergence of the Phoenician script was chosen because there is a gap in the epigraphic record; there are not actually any Phoenician inscriptions securely dated to the 11th century.[18] The oldest inscriptions are dated to the 10th century.

- KAI 1: Ahiram sarcophagus, Byblos, c. 1000 BC.

- KAI 14: Sarcophagus of Eshmunazar II, 5th century BC.

- KAI 15–16: Bodashtart inscriptions, 4th century BC.

- KAI 24: Kilamuwa Stela, 9th century BC.

- KAI 46: Nora Stone, c. 800 BC.

- KAI 47: Cippi of Melqart inscription, 2nd century BC.

- KAI 26: Karatepe bilingual, 8th century BC

- KAI 277: Pyrgi Tablets, Phoenician-Etruscan bilingual, c. 500 BC.

- Çineköy inscription, Phoenician-Luwian bilingual, 8th century BC.

(Note: KAI = Kanaanäische und Aramäische Inschriften)

Modern rediscovery

The Phoenician alphabet was deciphered in 1758 by

However, scholars could not find any link between the two writing systems, nor to hieratic or cuneiform. The theories of independent creation ranged from the idea of a single individual conceiving it, to the Hyksos people forming it from corrupt Egyptian.[20] [clarification needed] It was eventually discovered[clarification needed] that the Proto-Sinaitic alphabet was inspired by the model of hieroglyphs.

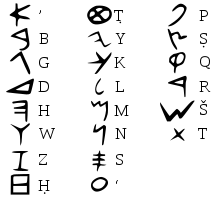

Table of letters

The chart shows the graphical evolution of Phoenician letter forms into other alphabets. The sound values also changed significantly, both at the initial creation of new alphabets and from gradual pronunciation changes which did not immediately lead to spelling changes.[21] The Phoenician letter forms shown are idealized: actual Phoenician writing is less uniform, with significant variations by era and region.

When alphabetic writing began, with the

The

| Origin | Letter | Name[22] | Meaning | Phoneme | Transliteration | Corresponding letter in | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Egyptian hieroglyphs | Proto-Sinaitic

|

Proto-Canaanite

|

Image | Text | Libyco-Berber | Samaritan

|

Aramaic | Hebrew | Syriac | Parthian | Arabic | South Arabian

|

Ge'ez

|

Greek | Latin | Cyrillic | Brahmi | Devanagari | Mongolian | ||||

| 𓃾 | 𐤀 | ʾālep | ox, head of cattle | ʾ [ʔ] | ʾ | ࠀ | 𐡀 | א | ܐ | 𐭀 | ﺍ, ء | 𐩱 | አ | Αα | Aa | А а

|

𑀅 /a/ | अ /a/ | (a / e / o / u / ö / ü) | ||||

| 𓉐 | 𐤁 | bēt | house | b [b] | b | ࠁ | 𐡁 | ב | ܒ | 𐭁 | ﺏ | 𐩨 | በ | Β β

|

Bb | В в

|

𑀩 /b/ | ब /b/ | (ē / w) | ||||

| 𓌙 | 𐤂 | gīml | throwing stick (or camel[23]) | g [ɡ] | g | ࠂ | 𐡂 | ג | ܓ | 𐭂 | ﺝ | 𐩴 | ገ | Γ γ

|

Cc, Gg | Ґ ґ

|

𑀕 /g/ | ग /g/ | (q / γ) | ||||

| 𓉿 | 𐤃 | dālet | door (or fish[23]) | d [ d ]

|

d | ࠃ | 𐡃 | ד | ܕ | 𐭃 | د, ذ | 𐩵 | ደ | Δ δ

|

Dd | Д д

|

𑀥 /dʰ/ | ध /dʰ/ | — | ||||

| 𓀠? | 𐤄 | he | window (or jubilation[23]) | h [h] | h | ࠄ | 𐡄 | ה | ܗ | 𐭄 | ه | 𐩠 | ሀ | Ε ε

|

Ee | Э э

|

𑀳 /ɦ/ | ह /ɦ/ | — | ||||

| 𓏲 | 𐤅 | wāw | hook | w [w] | w | ࠅ | 𐡅 | ו | ܘ | 𐭅 | ﻭ | 𐩥 | ወ | ( Υ υ

|

Ff, Uu, Vv, Ww, Yy | Ў ў

|

𑀯 /v/ | व /v/ | (o / u / ö / ü / w) | ||||

| 𓏭 | 𐤆 | zayin | weapon (or manacle[23]) | z [z] | z | ࠆ | 𐡆 | ז | ܙ | 𐭆 | ﺯ | 𐩸 | Ζ ζ

|

Zz | З з

|

𑀚 /ɟ/ | ज /dʒ/ | (s) | |||||

| 𓉗/𓈈? | 𐤇 | ḥēt | courtyard/wall[24] (?) | ḥ [ħ] | ḥ | ࠇ | 𐡇 | ח | ܚ | 𐭇 | ح, خ | 𐩢 | ሐ | Η η

|

Hh | Й й

|

𑀖 /gʰ/ | घ /gʰ/ | (q / γ) | ||||

| 𓄤? | 𐤈 | ṭēt | wheel[25] | ṭ [tˤ] | ṭ | ࠈ | 𐡈 | ט | ܛ | 𐭈 | ط, ظ | 𐩷 | ጠ | Θ θ

|

Ѳ ѳ

|

𑀣 /tʰ/ | थ /tʰ/ | — | |||||

| 𓂝 | 𐤉 | yod | arm, hand | y [j] | j | ࠉ | 𐡉 | י | ܝ | 𐭉 | ي | 𐩺 | የ | Ι ι

|

Ιi, Jj

|

Ј ј

|

𑀬 /j/ | य /j/ | (i / ǰ / y) | ||||

| 𓂧 | 𐤊 | kāp | palm of a hand | k [k] | k | ࠊ | 𐡊 | כך | ܟ | 𐭊 | ﻙ | 𐩫 | ከ | Κ κ

|

Kk | К к

|

𑀓 /k/ | क /k/ | (k / g) | ||||

| 𓌅 | 𐤋 | lāmed | goad[26] | l [ l ]

|

l | ࠋ | 𐡋 | ל | ܠ | 𐭋 | ﻝ | 𐩡 | ለ | Λ λ

|

Ll | Л л

|

𑀮 /l/ | ल /l/ | (t / d) | ||||

| 𓈖 | 𐤌 | mēm | water | m [m] | m | ࠌ | 𐡌 | מם | ܡ | 𐭌 | ﻡ | 𐩣 | መ | Μ μ

|

Mm | М м

|

𑀫 /m/ | म /m/ | (m) | ||||

| 𓆓 | 𐤍 | nūn | serpent (or fish[23][27]) | n [ n ]

|

n | ࠍ | 𐡍 | נן | ܢ | 𐭍 | ﻥ | 𐩬 | ነ | Ν ν

|

Nn | Н н

|

𑀦 /n/ | न /n/ | (n) | ||||

| 𓊽 | 𐤎 | śāmek | pillar(?) | ś [s] | s |

|

ࠎ | 𐡎 | ס | ܣ | 𐭎 | 𐩯 | Ξ ξ

|

Ѯ ѯ

|

𑀱 /ʂ/ | ष /ʂ/ | (s / š) | ||||||

| 𓁹 | 𐤏 | ʿayin | eye | ʿ [ʕ] | ʿ | ࠏ | 𐡏 | ע | ܥ | 𐭏 | غ

|

𐩲 | ዐ | Ω ω

|

Oo | Ѡ ѡ

|

𑀏 /e/ | ए /e/ | — | ||||

| 𓂋 | 𐤐 | pē | mouth (or corner[23]) | p [p] | p | ࠐ | 𐡐 | פף | ܦ | 𐭐 | ف | 𐩰 | ፈ | Ππ | Pp | П п

|

𑀧 /p/ | प /p/ | (b) | ||||

| 𓇑 ?[28] | — | 𐤑 | ṣādē | papyrus plant/fish hook? | ṣ [sˤ] | ṣ | ࠑ | 𐡑 | צץ | ܨ | 𐭑 | ص, ض | 𐩮 | ጸ | ( Ϻ ϻ)

|

𑀘 /c/ | च /tʃ/ | (č / ǰ) | |||||

| 𓃻? | 𐤒 | qōp | needle eye | q [q] | q | ࠒ | 𐡒 | ק | ܩ | 𐭒 | ﻕ | 𐩤 | ቀ | ( Φ φ

|

Ф ф

|

𑀔 /kʰ/ | ख /kʰ/ | — | |||||

| 𓁶 | 𐤓 | rēs, reš | head | r [ r ]

|

r | ࠓ | 𐡓 | ר | ܪ | 𐭓 | ﺭ | 𐩧 | ረ | Ρ ρ

|

Rr | Р р

|

𑀭 /r/ | र /r/ | (l),(r) | ||||

| 𓌓 | 𐤔 | šīn | tooth (or sun[23]) | š [ʃ] | š | ࠔ | 𐡔 | ש | ܫ | 𐭔 | س, ش | 𐩦 | ሠ | Σσς | Ss | Щ щ

|

𑀰 /ɕ/ | श /ɕ/ | (s / š) | ||||

| 𓏴 | 𐤕 | tāw | mark | t [ t ]

|

t | ࠕ | 𐡕 | ת | ܬ | 𐭕 | ت, ث | 𐩩 | ተ | Τ τ

|

Tt | Т т

|

𑀢 /t/ | त /t/ | (t / d) | ||||

Letter names

Phoenician used a system of acrophony to name letters: a word was chosen with each initial consonant sound, and became the name of the letter for that sound. These names were not arbitrary: each Phoenician letter was based on an Egyptian hieroglyph representing an Egyptian word; this word was translated into Phoenician (or a closely related Semitic language), then the initial sound of the translated word became the letter's Phoenician value.[29] For example, the second letter of the Phoenician alphabet was based on the Egyptian hieroglyph for "house" (a sketch of a house); the Semitic word for "house" was bet; hence the Phoenician letter was called bet and had the sound value b.

According to a 1904 theory by Theodor Nöldeke, some of the letter names were changed in Phoenician from the Proto-Canaanite script.[dubious ] This includes:

- gaml "throwing stick" to gimel "camel"

- digg "fish" to dalet "door"

- hll "jubilation" to he "window"

- ziqq "manacle" to zayin "weapon"

- naḥš "snake" to nun "fish"

- piʾt "corner" to pe "mouth"

- šimš "sun" to šin "tooth"

Yigael Yadin (1963) went to great lengths to prove that there was actual battle equipment similar to some of the original letter forms named for weapons (samek, zayin).[30]

Later, the Greeks kept (approximately) the Phoenician names, albeit they did not mean anything to them other than the letters themselves; on the other hand, the

Numerals

The Phoenician numeral system consisted of separate symbols for 1, 10, 20, and 100. The sign for 1 was a simple vertical stroke (𐤖). Other numerals up to 9 were formed by adding the appropriate number of such strokes, arranged in groups of three. The symbol for 10 was a horizontal line or tack (𐤗). The sign for 20 (𐤘) could come in different glyph variants, one of them being a combination of two 10-tacks, approximately Z-shaped. Larger multiples of ten were formed by grouping the appropriate number of 20s and 10s. There existed several glyph variants for 100 (𐤙). The 100 symbol could be multiplied by a preceding numeral, e.g. the combination of "4" and "100" yielded 400.

Derived alphabets

Phoenician is well prolific in terms of writing systems derived from it, as many of the writing systems in use today can ultimately trace their descent to it, and consequently Egyptian hieroglyphs. The Latin, Cyrillic, Armenian and Georgian scripts are derived from the Greek alphabet, which evolved from Phoenician; the Aramaic alphabet, also descended from Phoenician, evolved into the Arabic and Hebrew scripts. It has also been theorised that the Brahmi and subsequent Brahmic scripts of the Indian cultural sphere also descended from Aramaic, effectively uniting most of the world's writing systems under one family, although the theory is disputed.

Early Semitic scripts

The

Samaritan alphabet

The Phoenician alphabet continued to be used by the Samaritans and developed into the Samaritan alphabet, that is an immediate continuation of the Phoenician script without intermediate non-Israelite evolutionary stages. The Samaritans have continued to use the script for writing both Hebrew and Aramaic texts until the present day. A comparison of the earliest Samaritan inscriptions and the medieval and modern Samaritan manuscripts clearly indicates that the Samaritan script is a static script which was used mainly as a book hand.

Aramaic-derived

The Aramaic alphabet, used to write

By the 5th century BCE, among

The

The

Brahmic scripts

It has been proposed, notably by Georg Bühler (1898), that the

It is certain that the Aramaic-derived Kharosthi script was present in northern India by the 4th century BC, so that the Aramaic model of alphabetic writing would have been known in the region, but the link from Kharosthi to the slightly younger Brahmi is tenuous. Bühler's suggestion is still entertained in mainstream scholarship, but it has never been proven conclusively, and no definitive scholarly consensus exists.

Greek-derived

The

The

The

The

The

Paleohispanic scripts

These were an indigenous set of genetically related semisyllabaries, which suited the phonological characteristics of the Tartessian, Iberian and Celtiberian languages. They were deciphered in 1922 by Manuel Gómez-Moreno but their content is almost impossible to understand because they are not related to any living languages. While Gómez-Moreno first pointed to a joined Phoenician-Greek origin, following authors consider that their genesis has no relation to Greek.[39]

The most remote script of the group is the

Among the distinctive features of Paleohispanic scripts are:

- Semi-syllabism. Half of the signs represent syllables made of occlusive consonants (k g b d t) and the other half represent simple phonemes such as vowels (a e i o u) and continuant consonants (l n r ŕ s ś).

- Duality. Appears on the earliest Iberian and Celtiberian inscriptions and refers to how the signs can serve a double use by being modified with an extra stroke that transforms, for example ge with a stroke

becomes ke

becomes ke  . In later stages the scripts were simplified and duality vanishes from inscriptions.

. In later stages the scripts were simplified and duality vanishes from inscriptions. - Redundancy. A feature that appears only in the script of the Southwest, vowels are repeated after each syllabic signs.

Unicode

| Phoenician[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1090x | 𐤀 | 𐤁 | 𐤂 | 𐤃 | 𐤄 | 𐤅 | 𐤆 | 𐤇 | 𐤈 | 𐤉 | 𐤊 | 𐤋 | 𐤌 | 𐤍 | 𐤎 | 𐤏 |

| U+1091x | 𐤐 | 𐤑 | 𐤒 | 𐤓 | 𐤔 | 𐤕 | 𐤖 | 𐤗 | 𐤘 | 𐤙 | 𐤚 | 𐤛 | 𐤟 | |||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

See also

Notes

- destruction of Carthagein 149 BC.

- ^ Also called the Early Linear script in Semitic contexts, not to be conflated with Linear A, because it is an early development of the Proto-Sinaitic script

References

- ^ Himelfarb, Elizabeth J. (Jan–Feb 2000). "First Alphabet Found in Egypt". Archaeology. Vol. 53, no. 1.

- ISBN 978-1-861-89101-3.

- ^ S2CID 222445150.

- ^ Beyond Babel: A Handbook for Biblical Hebrew and Related Languages, article by Charles R. Krahmalkov (ed. John Kaltner, Steven L. McKenzie, 2002). "This alphabet was not, as often mistakenly asserted, invented by the Phoenicians but, rather, was an adaptation of the early West Semitic alphabet to the needs of their own language".

- ISBN 978-0-786-49033-2.

- ^ Beyond Babel: A Handbook for Biblical Hebrew and Related Languages, article by Charles R. Krahmalkov (ed. John Kaltner, Steven L. McKenzie, 2002). "This alphabet was not, as often mistakenly asserted, invented by the Phoenicians but, rather, was an adaptation of the early West Semitic alphabet to the needs of their own language".

- ^ Davidson, Lucy (18 March 2022). "How the Phoenician Alphabet Revolutionised Language". History Hit. United Kingdom. Retrieved 1 July 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-8032-9167-6. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- ^ Coulmas (1989) p. 141.

- ^ Markoe (2000) p. 111

- ^ Hock and Joseph (1996) p. 85.

- ^ Daniels (1996) p. 94-95.

- ^ "Discovery of Egyptian Inscriptions Indicates an Earlier Date for Origin of the Alphabet". Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ^ Fischer (2003) p. 68-69.

- ^ Herodotus, Histories, Book V, 58.

- ^ Herodotus. Histories, Book II, 145

- Zevahim 62a; Sanhedrin22a

- ISBN 978-0-8147-3654-8. Retrieved 23 May 2017.

By 1000 B.C.E., however, we see Phoenician writings [..]

- ^ Jensen (1969), p. 256.

- ^ Jensen (1969), pp. 256–258.

- OCLC 237631007.

- ^ after Fischer, Steven R. (2001). A History of Writing. London: Reaction Books. p. 126.

- ^ a b c d e f g Theodor Nöldeke (1904)[page needed]

- ^ The letters he and ḥēt continue three Proto-Sinaitic letters, ḥasir "courtyard", hillul "jubilation" and ḫayt "thread". The shape of ḥēt continues ḥasir "courtyard", but the name continues ḫayt "thread". The shape of he continues hillul "jubilation" but the name means "window".[citation needed] see: He (letter)#Origins.

- ^ The glyph was taken to represent a wheel, but it possibly derives from the hieroglyph nefer hieroglyph 𓄤 and would originally have been called tab טוב "good".

- ^ The root l-m-d mainly means "to teach", from an original meaning "to goad". H3925 in Strong’s Exhaustive Concordance to the Bible, 1979.

- ^ the letter name nūn is a word for "fish", but the glyph is presumably from the depiction of a snake, which would point to an original name נחש "snake".

- ^ the letter name may be from צד "to hunt".

- ^ Jensen (1969) p. 262-263.

- ^ Yigael Yadin, The Art of Warfare in Biblical Lands. McGraw-Hill, 1963. The samek – a quick war ladder, later to become the '$' dollar sign drawing the three internal lines quickly. The Z-shaped zayin – an ancient boomerang used for hunting. The H-shaped ḥet – mammoth tusks.

- ^ "Phoenician numerals in Unicode" (PDF). Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ^ "Number Systems". Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ^ Richard Salomon, "Brahmi and Kharoshthi", in The World's Writing Systems

- ISBN 9781594777943.

- ^ The Korean language reform of 1446: the origin, background, and Early History of the Korean Alphabet, Gari Keith Ledyard. University of California, 1966, p. 367–368.

- ^ Peter T. Daniels and William Bright, The World's Writing Systems (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), pp. 219–220

- ^ ISBN 9780313327636. Retrieved 2009-10-18.

- ^ Spurkland, Terje (2005): Norwegian Runes and Runic Inscriptions, translated by Betsy van der Hoek, Boydell Press, Woodbridge, pp. 3–4

- ISBN 978-84-00-09260-3.

- ISBN 2-914266-04-9

- María Eugenia Aubet, The Phoenicians and the West Second Edition, Cambridge University Press, London, 2001.

- Daniels, Peter T., et al. eds. The World's Writing Systems Oxford. (1996).

- Jensen, Hans, Sign, Symbol, and Script, G.P. Putman's Sons, New York, 1969.

- Coulmas, Florian, Writing Systems of the World, Blackwell Publishers Ltd, Oxford, 1989.

- Hock, Hans H. and Joseph, Brian D., Language History, Language Change, and Language Relationship, Mouton de Gruyter, New York, 1996.

- Fischer, Steven R., A History of Writing, Reaktion Books, 1999.

- Markoe, Glenn E., Phoenicians. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22613-5(2000) (hardback)

- "Alphabet, Hebrew". ISBN 965-07-0665-8

- Feldman, Rachel (2010). "Most ancient Hebrew biblical inscription deciphered". Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 15 June 2011.

- Shanks, Hershel (2010). "Oldest Hebrew Inscription Discovered in Israelite Fort on Philistine Border". Biblical Archaeology Review. 36 (2): 51–6. Archived from the original on 2012-02-29. Retrieved 2020-07-18.

External links

- Ancient Scripts.com (Phoenician)

- Omniglot.com (Phoenician alphabet)

- official Unicode standards document for Phoenician (PDF file)

- [1] Free-Libre GPL2 Licensed Unicode Phoenician Font

- GNU FreeFont Unicode font family with Phoenician range in its serif face.

- [2] Phönizisch TTF-Font.

- Ancient Hebrew and Aramaic on Coins, reading and transliterating Proto-Hebrew, online edition. (Judaea Coin Archive)

- Paleo-Hebrew Abjad font—also allows writing in Phoenician (the current version of the font is 1.1.0)