Phytoremediation

| Part of a series on |

| Pollution |

|---|

|

Phytoremediation technologies use living

Phytoremediation is proposed as a cost-effective plant-based approach of

Background

Soil remediation is an expensive and complicated process. Traditional methods involve removal of the contaminated soil followed by treatment and return of the treated soil.[citation needed]

Phytoremediation could in principle be a more cost effective solution.

Phytoremediation has been used successfully include the restoration of abandoned metal mine workings, and sites where

Not all plants are able to accumulate heavy metals or organics pollutants due to differences in the physiology of the plant.[9] Even cultivars within the same species have varying abilities to accumulate pollutants.[9]

Advantages and limitations

This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2020) |

- Advantages:

- the cost of the phytoremediation is lower than that of traditional processes[which?] both in situ and ex situ

- the possibility of the recovery and re-use of valuable metals (by companies specializing in "phyto mining")

- it preserves the topsoil, maintaining the fertility of the soil[10]

- Increase soil health, yield, and plant phytochemicals[11]

- the use of plants also reduces erosion and metal leaching in the soil[10]

- the cost of the phytoremediation is lower than that of traditional processes[

- Limitations:

- phytoremediation is limited to the surface area and depth occupied by the roots.

- with plant-based systems of remediation, it is not possible to completely prevent the leaching of contaminants into the groundwater (without the complete removal of the contaminated ground, which in itself does not resolve the problem of contamination)

- the survival of the plants is affected by the toxicity of the contaminated land and the general condition of the soil

- bio-accumulation of contaminants, especially metals, into the plants can affect consumer products like food and cosmetics, and requires the safe disposal of the affected plant material

- when taking up heavy metals, sometimes the metal is bound to the soil organic matter, which makes it unavailable for the plant to extract[citation needed]

Processes

A range of processes mediated by plants or algae are tested in treating environmental problems.:[citation needed]

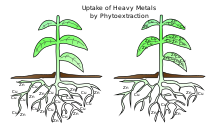

Phytoextraction

Phytoextraction (or phytoaccumulation or phytosequestration) exploits the ability of plants or algae to remove contaminants from soil or water into harvestable plant biomass. It is also used for the mining of metals such as copper(II) compounds. The roots take up substances from the soil or water and concentrate them above ground in the plant biomass

Of course many pollutants kill plants, so phytoremediation is not a panacea. For example, chromium is toxic to most higher plants at concentrations above 100 μM·kg−1 dry weight.[16]

Mining of these extracted metals through

Examples of plants that are known to accumulate the following contaminants:

- Cadmium, using willow (Salix viminalis): In 1999, one research experiment performed by Maria Greger and Tommy Landberg suggested willow has a significant potential as a phytoextractor of cadmium (Cd), zinc (Zn), and copper (Cu), as willow has some specific characteristics like high transport capacity of heavy metals from root to shoot and huge amount of biomass production; can be used also for production of bio energy in the biomass energy power plant.[21]

- On the other hand, the presence of copper seems to impair its growth (see table for reference).

- Solanum lycopersicum) show some promise.[23]

- poplar trees, which sequester lead in their biomass.

- Salt-tolerant (moderately sea water.

- Chernobyl accident.[24]

Phytostabilization

Phytostabilization reduces the mobility of substances in the environment, for example, by limiting the

Phytodegradation

Phytodegradation (also called phytotransformation) uses plants or microorganisms to degrade organic pollutants in the soil or within the body of the plant. The organic compounds are broken down by enzymes that the plant roots secrete and these molecules are then taken up by the plant and released through transpiration.[30] This process works best with organic contaminants like herbicides, trichloroethylene, and methyl tert-butyl ether.[15]

Phytotransformation results in the chemical modification of environmental substances as a direct result of plant

This is known as Phase I metabolism, similar to the way that the human liver increases the polarity of drugs and foreign compounds (drug metabolism). Whereas in the human liver enzymes such as cytochrome P450s are responsible for the initial reactions, in plants enzymes such as peroxidases, phenoloxidases, esterases and nitroreductases carry out the same role.[31]

In the second stage of phytotransformation, known as Phase II metabolism, plant biomolecules such as glucose and amino acids are added to the polarized xenobiotic to further increase the polarity (known as conjugation). This is again similar to the processes occurring in the human liver where

Phase I and II reactions serve to increase the polarity and reduce the toxicity of the compounds, although many exceptions to the rule are seen. The increased polarity also allows for easy transport of the xenobiotic along aqueous channels.[citation needed]

In the final stage of phytotransformation (Phase III metabolism), a sequestration of the xenobiotic occurs within the plant. The xenobiotics polymerize in a lignin-like manner and develop a complex structure that is sequestered in the plant. This ensures that the xenobiotic is safely stored, and does not affect the functioning of the plant. However, preliminary studies have shown that these plants can be toxic to small animals (such as snails), and, hence, plants involved in phytotransformation may need to be maintained in a closed enclosure.[citation needed]

Hence, the plants reduce toxicity (with exceptions) and sequester the xenobiotics in phytotransformation.

Phytostimulation

Phytostimulation (or rhizodegradation) is the enhancement of

Phytovolatilization

Phytovolatilization is the removal of substances from soil or water with release into the air, sometimes as a result of phytotransformation to more volatile and/or less polluting substances. In this process, contaminants are taken up by the plant and through transpiration, evaporate into the atmosphere.[30] This is the most studied form of phytovolatilization, where volatilization occurs at the stem and leaves of the plant, however indirect phytovolatilization occurs when contaminants are volatilized from the root zone.[38] Selenium (Se) and Mercury (Hg) are often removed from soil through phytovolatilization.[9] Poplar trees are one of the most successful plants for removing VOCs through this process due to its high transpiration rate.[15]

Rhizofiltration

Biological hydraulic containment

Biological hydraulic containment occurs when some plants, like poplars, draw water upwards through the soil into the roots and out through the plant, which decreases the movement of soluble contaminants downwards, deeper into the site and into the groundwater.[40]

Phytodesalination

Phytodesalination uses halophytes (plants adapted to saline soil) to extract salt from the soil to improve its fertility.[10]

Role of genetics

Breeding programs and

Hyperaccumulators and biotic interactions

A plant is said to be a hyperaccumulator if it can concentrate the pollutants in a minimum percentage which varies according to the pollutant involved (for example: more than 1000 mg/kg of dry weight for nickel, copper, cobalt, chromium or lead; or more than 10,000 mg/kg for zinc or manganese).[42] This capacity for accumulation is due to hypertolerance, or phytotolerance: the result of adaptative evolution from the plants to hostile environments through many generations. A number of interactions may be affected by metal hyperaccumulation, including protection, interferences with neighbour plants of different species, mutualism (including mycorrhizae, pollen and seed dispersal), commensalism, and biofilm.[43][44][45]

Tables of hyperaccumulators

- Hyperaccumulators table – 1 : Al, Ag, As, Be, Cr, Cu, Mn, Hg, Mo, Naphthalene, Pb, Pd, Pt, Se, Zn[citation needed]

- Hyperaccumulators table – 2 : Nickel[citation needed]

- Hyperaccumulators table – 3 : Radionuclides (Cd, Cs, Co, Pu, Ra, Sr, U), Hydrocarbons, Organic Solvents.[citation needed]

Phytoscreening

As plants are able to translocate and accumulate particular types of contaminants, plants can be used as biosensors of subsurface contamination, thereby allowing investigators to quickly delineate contaminant plumes.[46][47] Chlorinated solvents, such as trichloroethylene, have been observed in tree trunks at concentrations related to groundwater concentrations.[48] To ease field implementation of phytoscreening, standard methods have been developed to extract a section of the tree trunk for later laboratory analysis, often by using an increment borer.[49] Phytoscreening may lead to more optimized site investigations and reduce contaminated site cleanup costs.[citation needed]

See also

- Bioaugmentation

- Biodegradation

- Bioremediation

- Constructed wetland

- Mycorrhizal bioremediation

- Mycoremediation

- Phytotreatment

- De Ceuvel

References

- PMID 18698569.

- .

- ISSN 0269-7491.

- S2CID 241195507.

- PMID 23466085.

- ISSN 1582-9596.

- .

- ^ Phytoremediation of soils using Ralstonia eutropha, Pseudomonas tolaasi, Burkholderia fungorum reported by Sofie Thijs Archived 2012-03-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ PMID 18357623.

- ^ PMID 23466085.

- S2CID 91041080.

- ISSN 2073-4395.

- S2CID 207387747.

- ^ Guidi Nissim W., Palm E., Mancuso S., Azzarello E. (2018) "Trace element phytoextraction from contaminated soil: a case study under Mediterranean climate". Environmental Science and Pollution Research https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-018-1197-x

- ^ PMID 15862088.

- ^ PMID 15878200.

- ^ Morse, Ian (26 February 2020). "Down on the Farm That Harvests Metal From Plants". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- ^ PMID 18558420.

- PMID 17507235

- PMID 12428020

- .

- .

- S2CID 220073862.

- ^ Adler, Tina (July 20, 1996). "Botanical cleanup crews: using plants to tackle polluted water and soil". Science News. Archived from the original on July 15, 2011. Retrieved 2010-09-03.

- PMID 10712958.

- .

- PMID 18335091, archived from the originalon 2008-10-24.

- ^ ISBN 978-92-0-134110-5.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-319-41524-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Phytoremediation Processes". www.unep.or.jp. Archived from the original on 2019-01-02. Retrieved 2018-03-28.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-540-28996-8

- PMID 7894495.

- ]

- PMID 22493519.

- S2CID 28085176.

- ISSN 1097-4660.

- S2CID 97080119.

- PMID 27249664.

- S2CID 126742216.

- ISBN 9780470975152.

- S2CID 6965013.

- ^ Baker, A. J. M.; Brooks, R. R. (1989), "Terrestrial higher plants which hyperaccumulate metallic elements – A review of their distribution, ecology and phytochemistry", Biorecovery, 1 (2): 81–126.

- PMID 21557996. Retrieved 2021-12-09.

- S2CID 84954143.

- PMID 25709609.

- PMID 21749088.

- PMID 18284159.

- .

- ^ Vroblesky, D. (2008). "User's Guide to the Collection and Analysis of Tree Cores to Assess the Distribution of Subsurface Volatile Organic Compounds".

Bibliography

- "Phytoremediation Website" — Includes reviews, conference announcements, lists of companies doing phytoremediation, and bibliographies. Archived 2010-10-17 at the Wayback Machine

- "An Overview of Phytoremediation of Lead and Mercury" June 6 2000. The Hazardous Waste Clean-Up Information Web Site. Archived 2011-07-25 at the Wayback Machine

- "Enhanced phytoextraction of arsenic from contaminated soil using sunflower" September 22 2004. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

- "Phytoextraction", February 2000. Brookhaven National Laboratory 2000.

- "Phytoextraction of Metals from Contaminated Soil" April 18, 2001. M.M. Lasat

- July 2002. Donald Bren School of Environment Science & Management.

- "Phytoremediation" October 1997. Department of Civil Environmental Engineering. Archived 2006-06-22 at the Wayback Machine

- "Phytoremediation" June 2001, Todd Zynda.

- "Phytoremediation of Lead in Residential Soils in Dorchester, MA" May, 2002. Amy Donovan Palmer, Boston Public Health Commission.

- "Technology Profile: Phytoextraction" 1997. Environmental Business Association.

- Vassil AD, Kapulnik Y, Raskin I, Salt DE (June 1998), "The Role of EDTA in Lead Transport and Accumulation by Indian Mustard", Plant Physiol., 117 (2): 447–53, PMID 9625697.

- Salt, D. E.; Smith, R. D.; Raskin, I. (1998). "Phytoremediation". Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology. 49: 643–668. S2CID 241195507.

- Wang, X. J.; Li, F. Y.; Okazaki, M.; Sugisaki, M. (2003). "Phytoremediation of contaminated soil". Annual Report CESS. 3: 114–123.

- Ancona, V; Barra Caracciolo, A; Grenni, P; Di Lenola, M; Campanale, C; Calabrese, A; Uricchio, VF; Mascolo, G; Massacci, A (2017). "Plant-assisted bioremediation of a historically PCB and heavy metal-contaminated area in Southern Italy". New Biotechnology. 38 (Pt B): 65–73. PMID 27686395.

- "Ancona V, Barra Caracciolo A, Campanale C, De Caprariis B, Grenni P, Uricchio VF, Borello D, 2019. Gasification Treatment of Poplar Biomass Produced in a Contaminated Area Restored using Plant Assisted Bioremediation. Journal of Environmental Management"

External links

- Missouri Botanical Garden (host): Phytoremediation website Archived 2010-10-17 at the Wayback Machine — Review Articles, Conferences, Phytoremediation Links, Research Sponsors, Books and Journals, and Recent Research.

- International Journal of Phytoremediation — devoted to the publication of current laboratory and field research describing the use of plant systems to remediate contaminated environments.

- Using Plants To Clean Up Soils — from Agricultural Research magazine

- New Alchemy Institute — co-founded by John Todd (Canadian biologist)