Placoderm

| Placoderm | |

|---|---|

| |

| Fossil of pectoral fins

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Subphylum: | Vertebrata |

| Infraphylum: | Gnathostomata |

| Class: | †Placodermi McCoy, 1848 |

| Orders | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Placoderms (from Greek πλάξ (plax, plakos) '

Placoderms are thought to be

Placoderms were also the first fish

The first identifiable placoderms appear in the

Characteristics

Many placoderms, particularly the

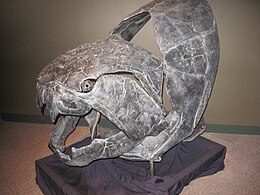

One of the largest known arthrodires, Dunkleosteus terrelli, was 3.5–4.1 metres (11–13 ft) long,[9] and is presumed to have had a large distribution, as its remains have been found in Europe, North America and possibly Morocco. Some paleontologists regard it as the world's first vertebrate "superpredator", preying upon other predators. Other, smaller arthrodires, such as Fallacosteus and Rolfosteus, both of the Gogo Formation of Western Australia, had streamlined, bullet-shaped head armor, and Amazichthys, with morphology like that of other fast-swimming pelagic organisms,[10] strongly supporting the idea that many, if not most, arthrodires were active swimmers, rather than passive ambush-hunters whose armor practically anchored them to the sea floor. Some placoderms were herbivorous, such as the Middle to Late Devonian arthrodire Holonema, and some were planktivores, such as the gigantic arthrodire Titanichthys, various members of Homostiidae, and Heterosteus.

Extraordinary evidence of internal fertilization in a placoderm was afforded by the discovery in the Gogo Formation, near

The placoderm claspers are not homologous with the claspers in cartilaginous fishes. The similarities between the structures has been revealed to be an example of convergent evolution. While the claspers in cartilaginous fishes are specialized parts of their paired pelvic fins that have been modified for copulation due to changes in the hox genes hoxd13, the origin of the mating organs in placoderms most likely relied on different sets of hox genes and were structures that developed further down the body as an extra and independent pair of appendages, but which during development turned into body parts used for reproduction only. Because they were not attached to the pelvic fins, as are the claspers in fish like sharks, they were much more flexible and could probably be rotated forward.[15]

Evolution and extinction

It was thought for a time that placoderms became extinct due to competition from the first bony fish and early sharks, given a combination of the supposed inherent superiority of bony fish and the presumed sluggishness of placoderms. With more accurate summaries of prehistoric organisms, it is now thought that they systematically died out as marine and freshwater ecologies suffered from the environmental catastrophes of the Late Devonian and end-Devonian extinctions.

Fossil record

The earliest identifiable placoderm fossils are of Chinese origin and date to the early Silurian. At that time, they were already differentiated into antiarchs and arthrodires, as well as other, more primitive, groups. Earlier fossils of basal Placodermi have not yet been discovered.

The Silurian fossil record of the placoderms is both literally and figuratively fragmented. Until the discovery of Silurolepis (and then, the discoveries of Entelognathus and Qilinyu), Silurian-aged placoderm specimens consisted of fragments. Some of them have been tentatively identified as antiarch or arthrodire due to histological similarities; and many of them have not yet been formally described or even named. The most commonly cited example of a Silurian placoderm, Wangolepis of Silurian China and possibly Vietnam, is known only from a few fragments that currently defy attempts to place them in any of the recognized placoderm orders. So far, only three officially described Silurian placoderms are known from more than scraps:

- the basal antiarch Ludlow epoch of Yunnan, China, known from an almost complete thoracic armor

- bony fish and tetrapods.

- Qilinyu, a close relative of Entelognathus that further links Entelognathus as a transitional form between placoderms and other stem-gnathostomes and crown-group gnathostomes.

The first officially described Silurian placoderm is an antiarch,

Paleontologists and placoderm specialists suspect that the scarcity of placoderms in the Silurian fossil record is due to placoderms' living in environments unconducive to fossil preservation, rather than a genuine scarcity. This hypothesis helps to explain the placoderms' seemingly instantaneous appearance and diversity at the very beginning of the Devonian.

During the Devonian, placoderms went on to inhabit and dominate almost all known aquatic ecosystems, both

History of study

The earliest studies of placoderms were published by

In the late 1920s, Dr. Erik Stensiö, at the Swedish Museum of Natural History in Stockholm, established the details of placoderm anatomy and identified them as true jawed fishes related to sharks. He took fossil specimens with well-preserved skulls and ground them away, one tenth of a millimeter at a time. After each layer had been removed, he made an imprint of the next surface in wax. Once the specimens had been completely ground away (and so destroyed), he made enlarged, three-dimensional models of the skulls to examine the anatomical details more thoroughly. Many other placoderm specialists thought that Stensiö was trying to shoehorn placoderms into a relationship with sharks; however, as more fossils were found, placoderms were accepted as a sister group of chondrichthyans.

Much later, the exquisitely preserved placoderm fossils from Gogo reef changed the picture again. They showed that placoderms shared anatomical features not only with chondrichthyans but with other

Placoderms also share certain anatomical features only with the jawless

Taxonomy and phylogeny

Currently, Placodermi are divided into eight recognized

Placoderm orders

Arthrodira

Antiarchi

Brindabellaspida

Phyllolepida

Phyllolepida ("leaf scales") were flattened placoderms found throughout the world. Like other flattened placoderms they were bottom-dwelling predators that ambushed prey. Unlike other flattened placoderms, they were freshwater fish. Their armour was made of whole plates, rather than the numerous tubercles and scales of Petalichthyida. The eyes were on the sides of the head, unlike visual bottom-dwelling predators, such as stargazers or flatfish, which have eyes on the top of their head. The orbits for the eyes were extremely small, suggesting the eyes were vestigial and that the phyllolepids may have been blind.

Ptyctodontida

Rhenanida

Acanthothoraci

Acanthothoraci ("spine chests") were a group of chimaera-like placoderms closely related to the rhenanid placoderms. Superficially, acanthoracids resembled scaly chimaeras or small, scaly arthrodires with blunt rostrums. They were distinguished from chimaeras by a pair of large spines that emanate from their chests, the presence of large scales and plates, tooth-like beak plates, and the typical bone-enhanced placoderm eyeball. They were distinguished from other placoderms due to differences in the anatomy of their skulls, and due to patterns on the skull plates and thoracic plates that are unique to this order. From what can be inferred from the mouthplates of fossil specimens, acanthothoracids were shellfish hunters ecologically similar to modern-day chimaeras. Competition with their relatives, the ptyctodont placoderms, may have been one of the main reasons for the acanthothoracids' extinction prior to the mid-Devonian extinction event.

Petalichthyida

Pseudopetalichthyida

Stensioellida

Cladogram

The following cladogram shows the interrelationships of placoderms according to Carr et al. (2009):[26]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

However, the cladogram had changed significantly over the years, and the placoderms are now thought to be

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

- Acanthodii

- List of placoderms

- Ostracoderm

- Chondrichthyes

- Entelognathus

Notes

- paraphyletic in relation to the rest of Gnathostomata, then modern jawed vertebrates represent extant forms.

References

Citations

- ^ Colbert, Edwin H. (Edwin Harris); Knight, Charles Robert (1951). The dinosaur book: the ruling reptiles and their relatives. New York: McGraw-Hill. p. 153.

- S2CID 235477130.

- PMID 27920231.

- ^ S2CID 4302415.

- ^ a b "Fossil reveals oldest live birth". BBC. May 28, 2008. Retrieved May 30, 2008.

- ^ .

- PMID 20479258.

- ^ Long 1983.

- ISSN 1424-2818.

- ISSN 2296-701X.

- ^ Long & Trinajstic 2010.

- ^ Long et al. 2008.

- ^ Long, Trinajstic & Johanson 2009.

- ^ Long 1984.

- ^ "The first vertebrate sexual organs evolved as an extra pair of legs". 8 June 2014. Archived from the original on 2016-12-20. Retrieved 2014-06-27.

- ^ Benton, M. J. (2005) Vertebrate Palaeontology, Blackwell, 3rd edition, Figure 3.25 on page 73.

- ISSN 1866-3508.

- ^ Wang Junqing (1991). "The Antiarchi from Early Silurian Hunan" (PDF). Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 21 (3): 240–244. INIST 19733953. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-12.

- S2CID 252569910.

- ^ Waggoner, Ben. "Introduction to the Placodermi". UCMP. Retrieved 18 July 2011.

- ^ Young, G.C.; Goujet, D.; Lelievre, H. (2001). "Extraocular muscles and cranial segmentation in primitive gnathostomes – fossil evidence". Journal of Morphology. 248: 304.

- ISBN 3-89937-052-X.

- Science Daily. June 6, 2008.

- ^ Carr, Robert K.; et al. (2010). "The ancestral morphotype for the gnathostome pectoral fin revisited and the placoderm condition". Academia.

- ^ "Philippe Janvier Tree of Life Contributor Profile".

- S2CID 45258255.

- PMID 25581798.

- S2CID 45922669.

Other references

- Ahlberg, P.E.; Trinajstic, K.; Johanson, Z.; Long, J.A. (2009). "Pelvic claspers confirm chondrichthyan-like internal fertilization in arthrodires". Nature. 460 (7257): 888–889. S2CID 205217467.

- Janvier, P. Early Vertebrates Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-19-854047-7

- Long, J. A. (May 1983). "New bothriolepid fish from the Late Devonian of Victoria, Australia | The Palaeontological Association". Palaeontology. 26 (2): 295–320.

- Long, J.A. (1984). "New phyllolepids from Victoria and the relationships of the group". Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales. 107: 263–308.

- Long, J.A. The Rise of Fishes: 500 Million Years of Evolution Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-8018-5438-5

- Long, J.A.; Trinajstic, K. (2010). "The Late Devonian Gogo Formation Lagerstatte – Exceptional preservation and Diversity in early Vertebrates". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 38: 255–279. .

- Long, J.A.; Trinajstic, K.; Young, G.C.; Senden, T. (2008). "Live birth in the Devonian". Nature. 453 (7195): 650–652. S2CID 205213348.

- Long, J.A.; Trinajstic, K.; Johanson, Z. (2009). "Devonian arthrodire embryos and the origin of internal fertilization in vertebrates". Nature. 457 (7233): 1124–1127. S2CID 205215898.

- Zhu, Min; Yu, Xiaobo; Choo, Brian; Wang, Junqing; Jia, Liantao (23 June 2012). "An antiarch placoderm shows that pelvic girdles arose at the root of jawed vertebrates". Biology Letters. 8 (3): 453–456. PMID 22219394.