Planet

A planet is a large,

The word planet probably comes from the Greek

With the development of the

Further advances in astronomy led to the discovery of over five thousand planets outside the Solar System, termed

Formation

It is not known with certainty how planets are built. The prevailing theory is that they are formed during the collapse of a

When the protostar has grown such that it ignites to form a star, the surviving disk is removed from the inside outward by photoevaporation, the solar wind, Poynting–Robertson drag and other effects.[17][18] Thereafter there still may be many protoplanets orbiting the star or each other, but over time many will collide, either to form a larger, combined protoplanet or release material for other protoplanets to absorb.[19] Those objects that have become massive enough will capture most matter in their orbital neighbourhoods to become planets. Protoplanets that have avoided collisions may become natural satellites of planets through a process of gravitational capture, or remain in belts of other objects to become either dwarf planets or small bodies.[20][21]

The energetic impacts of the smaller planetesimals (as well as radioactive decay) will heat up the growing planet, causing it to at least partially melt. The interior of the planet begins to differentiate by density, with higher density materials sinking toward the core.[22] Smaller terrestrial planets lose most of their atmospheres because of this accretion, but the lost gases can be replaced by outgassing from the mantle and from the subsequent impact of comets.[23] (Smaller planets will lose any atmosphere they gain through various escape mechanisms.[24])

With the discovery and observation of

Planets in the Solar System

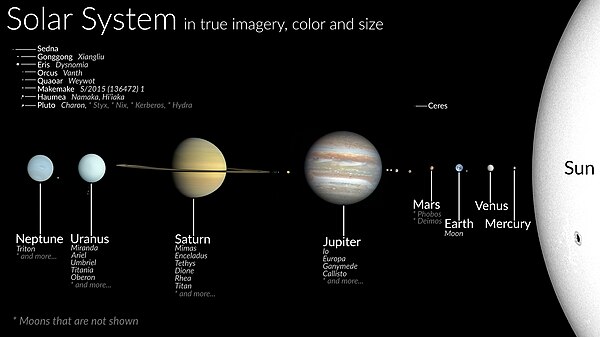

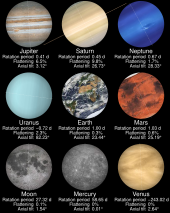

According to the IAU definition, there are eight planets in the Solar System, which are (in increasing distance from the Sun):[1] Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune. Jupiter is the largest, at 318 Earth masses, whereas Mercury is the smallest, at 0.055 Earth masses.[28]

The planets of the Solar System can be divided into categories based on their composition. Terrestrials are similar to Earth, with bodies largely composed of rock and metal: Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars. Earth is the largest terrestrial planet.[29] Giant planets are significantly more massive than the terrestrials: Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune.[29] They differ from the terrestrial planets in composition. The gas giants, Jupiter and Saturn, are primarily composed of hydrogen and helium and are the most massive planets in the Solar System. Saturn is one third as massive as Jupiter, at 95 Earth masses.[30] The ice giants, Uranus and Neptune, are primarily composed of low-boiling-point materials such as water, methane, and ammonia, with thick atmospheres of hydrogen and helium. They have a significantly lower mass than the gas giants (only 14 and 17 Earth masses).[30]

Dwarf planets are gravitationally rounded, but have not cleared their orbits of other bodies. In increasing order of average distance from the Sun, the ones generally agreed among astronomers are Ceres, Pluto, Haumea, Quaoar, Makemake, Gonggong, Eris, and Sedna.[31][32] Ceres is the largest object in the asteroid belt, located between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. The other seven all orbit beyond Neptune. Pluto, Haumea, Quaoar, and Makemake orbit in the Kuiper belt, which is a second belt of small Solar System bodies beyond the orbit of Neptune. Gonggong and Eris orbit in the scattered disc, which is somewhat further out and, unlike the Kuiper belt, is unstable towards interactions with Neptune. Sedna is the largest known detached object, a population that never comes close enough to the Sun to interact with any of the classical planets; the origins of their orbits are still being debated. All eight are similar to terrestrial planets in having a solid surface, but they are made of ice and rock rather than rock and metal. Moreover, all of them are smaller than Mercury, with Pluto being the largest known dwarf planet and Eris being the most massive known.[33][34]

There are at least nineteen planetary-mass moons or satellite planets—moons large enough to take on ellipsoidal shapes:[3]

- One satellite of Earth: the Moon

- Four satellites of Jupiter: Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto

- Seven satellites of Saturn:

- Five satellites of Uranus: Miranda, Ariel, Umbriel, Titania, and Oberon

- One satellite of Neptune: Triton

- One satellite of Pluto: Charon

The Moon, Io, and Europa have compositions similar to the terrestrial planets; the others are made of ice and rock like the dwarf planets, with Tethys being made of almost pure ice. (Europa is often considered an icy planet, though, because its surface ice layer makes it difficult to study its interior.[3][35]) Ganymede and Titan are larger than Mercury by radius, and Callisto almost equals it, but all three are much less massive. Mimas is the smallest object generally agreed to be a geophysical planet, at about six millionths of Earth's mass, though there are many larger bodies that may not be geophysical planets (e.g. Orcus and Salacia).[31]

Exoplanets

An exoplanet (exoplanet) is a planet outside the Solar System. As of 1 April 2024, there are 5,653 confirmed exoplanets in 4,161 planetary systems, with 896 systems having more than one planet.[37] Known exoplanets range in size from gas giants about twice as large as Jupiter down to just over the size of the Moon. Analysis of gravitational microlensing data suggests a minimum average of 1.6 bound planets for every star in the Milky Way.[38]

In early 1992, radio astronomers

The first confirmed discovery of an exoplanet orbiting an ordinary main-sequence star occurred on 6 October 1995, when

In 2011, the

There are types of planets that do not exist in the Solar System: super-Earths and mini-Neptunes, which have masses between that of Earth and Neptune. Objects less than about twice the mass of Earth are expected to be rocky like Earth; beyond that, they become a mixture of volatiles and gas like Neptune.[53] The planet Gliese 581c, with mass 5.5–10.4 times the mass of Earth,[54] attracted attention upon its discovery for potentially being in the habitable zone,[55] though later studies concluded that it is actually too close to its star to be habitable.[56] Planets more massive than Jupiter are also known, extending seamlessly into the realm of brown dwarfs.[57]

Exoplanets have been found that are much closer to their parent star than any planet in the Solar System is to the Sun. Mercury, the closest planet to the Sun at 0.4 AU, takes 88 days for an orbit, but ultra-short period planets can orbit in less than a day. The Kepler-11 system has five of its planets in shorter orbits than Mercury's, all of them much more massive than Mercury. There are hot Jupiters, such as 51 Pegasi b,[41] that orbit very close to their star and may evaporate to become chthonian planets, which are the leftover cores. There are also exoplanets that are much farther from their star. Neptune is 30 AU from the Sun and takes 165 years to orbit, but there are exoplanets that are thousands of AU from their star and take more than a million years to orbit. e.g. COCONUTS-2b.[58]

Attributes

Although each planet has unique physical characteristics, a number of broad commonalities do exist among them. Some of these characteristics, such as rings or natural satellites, have only as yet been observed in planets in the Solar System, whereas others are commonly observed in exoplanets.[59]

Dynamic characteristics

Orbit

In the Solar System, all the planets orbit the Sun in the same direction as the Sun rotates:

No planet's orbit is perfectly circular, and hence the distance of each from the host star varies over the course of its year. The closest approach to its star is called its

Each planet's orbit is delineated by a set of elements:

- The eccentricity of an orbit describes the elongation of a planet's elliptical (oval) orbit. Planets with low eccentricities have more circular orbits, whereas planets with high eccentricities have more elliptical orbits. The planets and large moons in the Solar System have relatively low eccentricities, and thus nearly circular orbits.[61] The comets and many Kuiper belt objects, as well as several exoplanets, have very high eccentricities, and thus exceedingly elliptical orbits.[63][64]

- The semi-major axis gives the size of the orbit. It is the distance from the midpoint to the longest diameter of its elliptical orbit. This distance is not the same as its apastron, because no planet's orbit has its star at its exact centre.[61]

- The inclination of a planet tells how far above or below an established reference plane its orbit is tilted. In the Solar System, the reference plane is the plane of Earth's orbit, called the ecliptic. For exoplanets, the plane, known as the sky plane or plane of the sky, is the plane perpendicular to the observer's line of sight from Earth.[65] The orbits of the eight major planets of the Solar System all lie very close to the ecliptic; however, some smaller objects like Pallas, Pluto, and Eris orbit at far more extreme angles to it, as do comets.[66] The large moons are generally not very inclined to their parent planets' equators, but Earth's Moon, Saturn's Iapetus, and Neptune's Triton are exceptions. Triton is unique among the large moons in that it orbits retrograde, i.e. in the direction opposite to its parent planet's rotation.[67]

- The points at which a planet crosses above and below its reference plane are called its descending nodes.[61] The longitude of the ascending node is the angle between the reference plane's 0 longitude and the planet's ascending node. The argument of periapsis (or perihelion in the Solar System) is the angle between a planet's ascending node and its closest approach to its star.[61]

Axial tilt

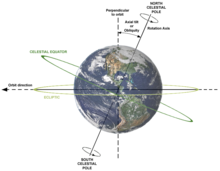

Planets have varying degrees of axial tilt; they spin at an angle to the

Rotation

The planets rotate around invisible axes through their centres. A planet's

The rotation of a planet can be induced by several factors during formation. A net angular momentum can be induced by the individual angular momentum contributions of accreted objects. The accretion of gas by the giant planets contributes to the angular momentum. Finally, during the last stages of planet building, a stochastic process of protoplanetary accretion can randomly alter the spin axis of the planet.[80] There is great variation in the length of day between the planets, with Venus taking 243 days to rotate, and the giant planets only a few hours.[81] The rotational periods of exoplanets are not known, but for hot Jupiters, their proximity to their stars means that they are tidally locked (that is, their orbits are in sync with their rotations). This means, they always show one face to their stars, with one side in perpetual day, the other in perpetual night.[82] Mercury and Venus, the closest planets to the Sun, similarly exhibit very slow rotation: Mercury is tidally locked into a 3:2 spin–orbit resonance (rotating three times for every two revolutions around the Sun),[83] and Venus' rotation may be in equilibrium between tidal forces slowing it down and atmospheric tides created by solar heating speeding it up.[84][85]

All the large moons are tidally locked to their parent planets;

Orbital clearing

The defining dynamic characteristic of a planet, according to the IAU definition, is that it has cleared its neighborhood. A planet that has cleared its neighborhood has accumulated enough mass to gather up or sweep away all the

Physical characteristics

Size and shape

Gravity causes planets to be pulled into a roughly spherical shape, so a planet's size can be expressed roughly by an average radius (for example,

Mass

A planet's defining physical characteristic is that it is massive enough for the force of its own gravity to dominate over the

Mass is the prime attribute by which planets are distinguished from stars. No objects between the masses of the Sun and Jupiter exist in the Solar System; but there are exoplanets of this size. The lower

The smallest known exoplanet with an accurately known mass is

Internal differentiation

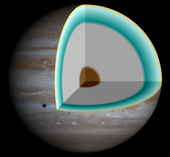

Every planet began its existence in an entirely fluid state; in early formation, the denser, heavier materials sank to the centre, leaving the lighter materials near the surface. Each therefore has a

Atmosphere

All of the Solar System planets except Mercury[116] have substantial atmospheres because their gravity is strong enough to keep gases close to the surface. Saturn's largest moon Titan also has a substantial atmosphere thicker than that of Earth;[117] Neptune's largest moon Triton[118] and the dwarf planet Pluto have more tenuous atmospheres.[119] The larger giant planets are massive enough to keep large amounts of the light gases hydrogen and helium, whereas the smaller planets lose these gases into space.[120] Analysis of exoplanets suggests that the threshold for being able to hold on to these light gases occurs at about 2.0+0.7

−0.6 ME, so that Earth and Venus are near the maximum size for rocky planets.[53]

The composition of Earth's atmosphere is different from the other planets because the various life processes that have transpired on the planet have introduced free molecular oxygen.[121] The atmospheres of Mars and Venus are both dominated by carbon dioxide, but differ drastically in density: the average surface pressure of Mars' atmosphere is less than 1% that of Earth's (too low to allow liquid water to exist),[122] while the average surface pressure of Venus' atmosphere is about 92 times that of Earth's.[123] It is likely that Venus' atmosphere was the result of a runaway greenhouse effect in its history, which today makes it the hottest planet by surface temperature, hotter even than Mercury.[124] Despite hostile surface conditions, temperature, and pressure at about 50–55 km altitude in Venus' atmosphere are close to Earthlike conditions (the only place in the Solar System beyond Earth where this is so), and this region has been suggested as a plausible base for future human exploration.[125] Titan has the only nitrogen-rich planetary atmosphere in the Solar System other than Earth's. Just as Earth's conditions are close to the triple point of water, allowing it to exist in all three states on the planet's surface, so Titan's are to the triple point of methane.[126]

Planetary atmospheres are affected by the varying

Hot Jupiters, due to their extreme proximities to their host stars, have been shown to be losing their atmospheres into space due to stellar radiation, much like the tails of comets.[131][132] These planets may have vast differences in temperature between their day and night sides that produce supersonic winds,[133] although multiple factors are involved and the details of the atmospheric dynamics that affect the day-night temperature difference are complex.[134][135]

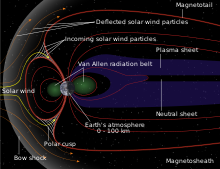

Magnetosphere

One important characteristic of the planets is their intrinsic

Of the eight planets in the Solar System, only Venus and Mars lack such a magnetic field.

In 2003, a team of astronomers in Hawaii observing the star HD 179949 detected a bright spot on its surface, apparently created by the magnetosphere of an orbiting hot Jupiter.[138][139]

Secondary characteristics

Several planets or dwarf planets in the Solar System (such as Neptune and Pluto) have orbital periods that are in resonance with each other or with smaller bodies. This is common in satellite systems (e.g. the resonance between Io, Europa, and Ganymede around Jupiter, or between Enceladus and Dione around Saturn). All except Mercury and Venus have natural satellites, often called "moons". Earth has one, Mars has two, and the giant planets have numerous moons in complex planetary-type systems. Except for Ceres and Sedna, all the consensus dwarf planets are known to have at least one moon as well. Many moons of the giant planets have features similar to those on the terrestrial planets and dwarf planets, and some have been studied as possible abodes of life (especially Europa and Enceladus).[140][141][142][143][144]

The four giant planets are orbited by

No secondary characteristics have been observed around exoplanets. The

History and etymology

The idea of planets has evolved over its history, from the divine lights of antiquity to the earthly objects of the scientific age. The concept has expanded to include worlds not only in the Solar System, but in multitudes of other extrasolar systems. The consensus as to what counts as a planet, as opposed to other objects, has changed several times. It previously encompassed asteroids, moons, and dwarf planets like Pluto,[151][152][153] and there continues to be some disagreement today.[153]

Ancient civilizations and classical planets

The five

Babylon

The first civilization known to have a functional theory of the planets were the

Greco-Roman astronomy

The

By the 1st century BC, during the Hellenistic period, the Greeks had begun to develop their own mathematical schemes for predicting the positions of the planets. These schemes, which were based on geometry rather than the arithmetic of the Babylonians, would eventually eclipse the Babylonians' theories in complexity and comprehensiveness and account for most of the astronomical movements observed from Earth with the naked eye. These theories would reach their fullest expression in the Almagest written by Ptolemy in the 2nd century CE. So complete was the domination of Ptolemy's model that it superseded all previous works on astronomy and remained the definitive astronomical text in the Western world for 13 centuries.[163][173] To the Greeks and Romans, there were seven known planets, each presumed to be circling Earth according to the complex laws laid out by Ptolemy. They were, in increasing order from Earth (in Ptolemy's order and using modern names): the Moon, Mercury, Venus, the Sun, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn.[158][173][174]

Medieval astronomy

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, astronomy developed further in India and the medieval Islamic world. In 499 CE, the Indian astronomer Aryabhata propounded a planetary model that explicitly incorporated Earth's rotation about its axis, which he explains as the cause of what appears to be an apparent westward motion of the stars. He also theorised that the orbits of planets were elliptical.[175] Aryabhata's followers were particularly strong in South India, where his principles of the diurnal rotation of Earth, among others, were followed and a number of secondary works were based on them.[176]

The astronomy of the

Scientific Revolution and discovery of outer planets

With the advent of the

When four satellites of Jupiter (the Galilean moons) and five of Saturn were discovered in the 17th century, they were thought of as "satellite planets" or "secondary planets" orbiting the primary planets, though in the following decades they would come to be called simply "satellites" for short. Scientists generally considered planetary satellites to also be planets until about the 1920s, although this usage was not common among non-scientists.[153]

In the first decade of the 19th century, four new 'planets' were discovered: Ceres (in 1801), Pallas (in 1802), Juno (in 1804), and Vesta (in 1807). It soon became apparent that they were rather different from previously known planets: they shared the same general region of space, between Mars and Jupiter (the asteroid belt), with sometimes overlapping orbits. This was an area where only one planet had been expected, and they were much much smaller than all other planets; indeed, it was suspected that they might be shards of a larger planet that had broken up. Herschel called them asteroids (from the Greek for "starlike") because even in the largest telescopes they resembled stars, without a resolvable disk.[152][182]

The situation was stable for four decades, but in the 1840s several additional asteroids were discovered (

Neptune was discovered in 1846, its position having been predicted thanks to its gravitational influence upon Uranus. Because the orbit of Mercury appeared to be affected in a similar way, it was believed in the late 19th century that there might be another planet even closer to the Sun. However, the discrepancy between Mercury's orbit and the predictions of Newtonian gravity was instead explained by an improved theory of gravity, Einstein's general relativity.[184][185]

In the 1950s, Gerard Kuiper published papers on the origin of the asteroids. He recognised that asteroids were typically not spherical, as had previously been thought, and that the asteroid families were remnants of collisions. Thus he differentiated between the largest asteroids as "true planets" versus the smaller ones as collisional fragments. From the 1960s onwards, the term "minor planet" was mostly displaced by the term "asteroid", and references to the asteroids as planets in the literature became scarce, except for the geologically evolved largest three: Ceres, and less often Pallas and Vesta.[183]

The beginning of Solar System exploration by space probes in the 1960s spurred a renewed interest in planetary science. A split in definitions regarding satellites occurred around then: planetary scientists began to reconsider the large moons as also being planets, but astronomers who were not planetary scientists generally did not.[153] (This is not exactly the same as the definition used in the previous century, which classed all satellites as secondary planets, even non-round ones like Saturn's Hyperion or Mars' Phobos and Deimos.)[192][193]

Redefining the term planet

A growing number of astronomers argued for Pluto to be declassified as a planet, because many similar objects approaching its size had been found in the same region of the Solar System (the

The announcement of Eris in 2005, an object 27% more massive than Pluto, created the impetus for an official definition of a planet,[194] as considering Pluto a planet would logically have demanded that Eris be considered a planet as well. Since different procedures were in place for naming planets versus non-planets, this created an urgent situation because under the rules Eris could not be named without defining what a planet was.[153] At the time, it was also thought that the size required for a trans-Neptunian object to become round was about the same as that required for the moons of the giant planets (about 400 km diameter), a figure that would have suggested about 200 round objects in the Kuiper belt and thousands more beyond.[196][197] Many astronomers argued that the public would not accept a definition creating a large number of planets.[153]

- Object is in

cleared the neighbourhoodaround its orbitSource: "IAU 2006 General Assembly: Resolutions 5 and 6" (PDF). IAU. 24 August 2006. Retrieved 23 June 2009.

To acknowledge the problem, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) set about creating the definition of planet and produced one in August 2006. Under this definition, the Solar System is considered to have eight planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune). Bodies that fulfill the first two conditions but not the third are classified as dwarf planets, provided they are not natural satellites of other planets. Originally an IAU committee had proposed a definition that would have included a larger number of planets as it did not include (c) as a criterion.[198] After much discussion, it was decided via a vote that those bodies should instead be classified as dwarf planets.[191][199]

Criticisms and alternatives to IAU definition

The IAU definition has not been universally used or accepted. In planetary geology, celestial objects have been assessed and defined as planets by geophysical characteristics. Planetary scientists are more interested in planetary geology than dynamics, so they classify planets based on their geological properties. A celestial body may acquire a dynamic (planetary) geology at approximately the mass required for its mantle to become plastic under its own weight. This leads to a state of hydrostatic equilibrium where the body acquires a stable, round shape, which is adopted as the hallmark of planethood by geophysical definitions. For example:[200]

a substellar-mass body that has never undergone nuclear fusion and has enough gravitation to be round due to hydrostatic equilibrium, regardless of its orbital parameters.[201]

In the Solar System, this mass is generally less than the mass required for a body to clear its orbit; thus, some objects that are considered "planets" under geophysical definitions are not considered as such under the IAU definition, such as Ceres and Pluto.[3] (In practice, the requirement for hydrostatic equilibrium is universally relaxed to a requirement for rounding and compaction under self-gravity; Mercury is not actually in hydrostatic equilibrium,[202] but is universally included as a planet regardless.)[203] Proponents of such definitions often argue that location should not matter and that planethood should be defined by the intrinsic properties of an object.[3] Dwarf planets had been proposed as a category of small planet (as opposed to planetoids as sub-planetary objects) and planetary geologists continue to treat them as planets despite the IAU definition.[31]

The number of dwarf planets even among known objects is not certain. In 2019, Grundy et al. argued based on the low densities of some mid-sized trans-Neptunian objects that the limiting size required for a trans-Neptunian object to reach equilibrium was in fact much larger than it is for the icy moons of the giant planets, being about 900–1000 km diameter.[31] There is general consensus on Ceres in the asteroid belt[204] and on the seven trans-Neptunians that probably cross this threshold – Quaoar, Sedna, Pluto, Haumea, Eris, Makemake, and Gonggong.[205][32]

Planetary geologists may include the nineteen known

Astronomer Jean-Luc Margot proposed a mathematical criterion that determines whether an object can clear its orbit during the lifetime of its host star, based on the mass of the planet, its semimajor axis, and the mass of its host star.[209] The formula produces a value called π that is greater than 1 for planets.[b] The eight known planets and all known exoplanets have π values above 100, while Ceres, Pluto, and Eris have π values of 0.1, or less. Objects with π values of 1 or more are expected to be approximately spherical, so that objects that fulfill the orbital-zone clearance requirement around Sun-like stars will also fulfill the roundness requirement.[210]

Exoplanets

Even before the discovery of exoplanets, there were particular disagreements over whether an object should be considered a planet if it was part of a distinct population such as a

In 1992, astronomers Aleksander Wolszczan and Dale Frail announced the discovery of planets around a pulsar, PSR B1257+12.[39] This discovery is generally considered to be the first definitive detection of a planetary system around another star. Then, on 6 October 1995, Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz of the Geneva Observatory announced the first definitive detection of an exoplanet orbiting an ordinary main-sequence star (51 Pegasi).[212]

The discovery of exoplanets led to another ambiguity in defining a planet: the point at which a planet becomes a star. Many known exoplanets are many times the mass of Jupiter, approaching that of stellar objects known as brown dwarfs. Brown dwarfs are generally considered stars due to their theoretical ability to fuse deuterium, a heavier isotope of hydrogen. Although objects more massive than 75 times that of Jupiter fuse simple hydrogen, objects of 13 Jupiter masses can fuse deuterium. Deuterium is quite rare, constituting less than 0.0026% of the hydrogen in the galaxy, and most brown dwarfs would have ceased fusing deuterium long before their discovery, making them effectively indistinguishable from supermassive planets.[213]

IAU working definition of exoplanets

The 2006 IAU definition presents some challenges for exoplanets because the language is specific to the Solar System and the criteria of roundness and orbital zone clearance are not presently observable for exoplanets.[214] In 2018, this definition was reassessed and updated as knowledge of exoplanets increased.[215] The current official working definition of an exoplanet is as follows:[98]

- Objects with true masses below the limiting mass for thermonuclear fusion of deuterium (currently calculated to be 13 Jupiter masses for objects of solar metallicity) that orbit stars, brown dwarfs, or stellar remnants and that have a mass ratio with the central object below the L4/L5 instability (M/Mcentral < 2/(25+√621) are "planets" (no matter how they formed). The minimum mass/size required for an extrasolar object to be considered a planet should be the same as that used in our Solar System.

- Substellar objects with true masses above the limiting mass for thermonuclear fusion of deuterium are "brown dwarfs", no matter how they formed nor where they are located.

- Free-floating objects in young star clusters with masses below the limiting mass for thermonuclear fusion of deuterium are not "planets", but are "sub-brown dwarfs" (or whatever name is most appropriate).[98]

The IAU noted that this definition could be expected to evolve as knowledge improves.[98] A 2022 review article discussing the history and rationale of this definition suggested that the words "in young star clusters" should be deleted in clause 3, as such objects have now been found elsewhere, and that the term "sub-brown dwarfs" should be replaced by the more current "free-floating planetary mass objects". The term "planetary mass object" has also been used to refer to ambiguous situations concerning exoplanets, such as objects with mass typical for a planet that are free-floating or orbit a brown dwarf instead of a star.[215]

The limit of 13 Jupiter masses is not universally accepted. Objects below this mass limit can sometimes burn deuterium, and the amount of deuterium that is burned depends on an object's composition.[216][217] Furthermore, deuterium is quite scarce, so the stage of deuterium burning does not actually last very long; unlike hydrogen burning in a star, deuterium burning does not significantly affect the future evolution of an object.[57] The relationship between mass and radius (or density) show no special feature at this limit, according to which brown dwarfs have the same physics and internal structure as lighter Jovian planets, and would more naturally be considered planets.[57][53]

Thus, many catalogues of exoplanets include objects heavier than 13 Jupiter masses, sometimes going up to 60 Jupiter masses.[218][99][100][219] (The limit for hydrogen burning and becoming a red dwarf star is about 80 Jupiter masses.)[57] The situation of main-sequence stars has been used to argue for such an inclusive definition of "planet" as well, as they also differ greatly along the two orders of magnitude that they cover, in their structure, atmospheres, temperature, spectral features, and probably formation mechanisms; yet they are all considered as one class, being all hydrostatic-equilibrium objects undergoing nuclear burning.[57]

Mythology and naming

The naming of planets differs between planets of the Solar System and exoplanets (planets of other planetary systems). exoplanets are commonly named after their parent star and their order of discovery within its planetary system, such as Proxima Centauri b.

The names for the planets of the

In ancient Greece, the two great luminaries, the Sun and the Moon, were called

- Helios and Selene were the names of both planets and gods, both of them Titans (later supplanted by Olympians Apollo and Artemis);

- Phainon was sacred to Cronus, the Titan who fathered the Olympians;

- Phaethon was sacred to Zeus, Cronus's son who deposed him as king;

- Pyroeis was given to Ares, son of Zeus and god of war;

- Phosphoros was ruled by Aphrodite, the goddess of love; and

- Stilbon with its speedy motion, was ruled over by Hermes, messenger of the gods and god of learning and wit.[163]

Although modern Greeks still use their ancient names for the planets, other European languages, because of the influence of the

Earth's name in English is not derived from Greco-Roman mythology. Because it was only generally accepted as a planet in the 17th century,

Non-European cultures use other planetary-naming systems.

The native Persian names of most of the planets are based on identifications of the Mesopotamian gods with Iranian gods, analogous to the Greek and Latin names. Mercury is Tir (Persian: تیر) for the western Iranian god Tīriya (patron of scribes), analogous to Nabu; Venus is Nāhid (ناهید) for Anahita; Mars is Bahrām (بهرام) for Verethragna; and Jupiter is Hormoz (هرمز) for Ahura Mazda. The Persian name for Saturn, Keyvān (کیوان), is a borrowing from Akkadian kajamānu, meaning "the permanent, steady".[232]

China and the countries of eastern Asia historically subject to

In traditional Hebrew astronomy, the seven traditional planets have (for the most part) descriptive names – the Sun is חמה Ḥammah or "the hot one", the Moon is לבנה Levanah or "the white one", Venus is כוכב נוגה Kokhav Nogah or "the bright planet", Mercury is כוכב Kokhav or "the planet" (given its lack of distinguishing features), Mars is מאדים Ma'adim or "the red one", and Saturn is שבתאי Shabbatai or "the resting one" (in reference to its slow movement compared to the other visible planets).[237] The odd one out is Jupiter, called צדק Tzedeq or "justice".[237] Hebrew names were chosen for Uranus (אורון Oron, "small light") and Neptune (רהב Rahab, a Biblical sea monster) in 2009;[238] prior to that the names "Uranus" and "Neptune" had simply been borrowed.[239] The etymologies for the Arabic names of the planets are less well understood. Mostly agreed among scholars are Venus (Arabic: الزهرة, az-Zuhara, "the bright one"[240]), Earth (الأرض, al-ʾArḍ, from the same root as eretz), and Saturn (زُحَل, Zuḥal, "withdrawer"[241]). Multiple suggested etymologies exist for Mercury (عُطَارِد, ʿUṭārid), Mars (اَلْمِرِّيخ, al-Mirrīkh), and Jupiter (المشتري, al-Muštarī), but there is no agreement among scholars.[242][243][244][245]

When subsequent planets were discovered in the 18th and 19th centuries, Uranus was named for a

The moons (including the planetary-mass ones) are generally given names with some association with their parent planet. The planetary-mass moons of Jupiter are named after four of Zeus' lovers (or other sexual partners); those of Saturn are named after Cronus' brothers and sisters, the Titans; those of Uranus are named after characters from Shakespeare and Pope (originally specifically from fairy mythology,[249] but that ended with the naming of Miranda). Neptune's planetary-mass moon Triton is named after the god's son; Pluto's planetary-mass moon Charon is named after the ferryman of the dead, who carries the souls of the newly deceased to the underworld (Pluto's domain).[250]

Symbols

| Sun |

Mercury |

Venus |

Earth |

Moon |

Mars |

Jupiter |

Saturn |

Uranus |

Neptune |

The written symbols for Mercury, Venus, Jupiter, Saturn, and possibly Mars have been traced to forms found in late Greek papyrus texts.[251] The symbols for Jupiter and Saturn are identified as monograms of the corresponding Greek names, and the symbol for Mercury is a stylized caduceus.[251]

According to

When further planets were discovered orbiting the Sun, symbols were invented for them. The most common astronomical symbol for Uranus, ⛢,

| Earth |

Vesta |

Juno |

Ceres |

Pallas |

Hygiea |

Orcus |

Pluto |

Haumea |

Quaoar |

Makemake |

Gonggong |

Eris |

Sedna |

The IAU discourages the use of planetary symbols in modern journal articles in favour of one-letter or (to disambiguate Mercury and Mars) two-letter abbreviations for the major planets. The symbols for the Sun and Earth are nonetheless common, as solar mass, Earth mass, and similar units are common in astronomy.[261] Other planetary symbols today are mostly encountered in astrology. Astrologers have resurrected the old astronomical symbols for the first few asteroids and continue to invent symbols for other objects.[260] Unicode includes some relatively standard astrological symbols for minor planets, including dwarf planets discovered in the 21st century, though astronomical use of any of them is rare. In particular, the Eris symbol is a traditional one from Discordianism, a religion worshipping the goddess Eris. The other dwarf-planet symbols are mostly initialisms (except Haumea) in the native scripts of the cultures they come from; they also represent something associated with the corresponding deity or culture, e.g. Makemake's face or Gonggong's snake-tail.[260][262]

See also

- Double planet – A binary system where two planetary-mass objects share an orbital axis external to both

- List of landings on extraterrestrial bodies

- Lists of planets – A list of lists of planets sorted by diverse attributes

- Mesoplanet – Planetary objects that have a mass smaller than Mercury but larger than Ceres

- Planetary habitability – Known extent to which a planet is suitable for life

- Planetary mnemonic – Phrase used to remember the planets of the Solar System

- Theoretical planetology – Scientific modeling of planets

Notes

- ^ Margot's parameter[210] is not to be confused with the famous mathematical constant π≈3.14159265 ... .

- ^ In Korean, these names are more often written in Hangul rather than Chinese characters, e.g. 명왕성 for Pluto. In Vietnamese, calques are more common than directly reading these names as Sino-Vietnamese, e.g. sao Thuỷ rather than Thuỷ tinh for Mercury. Pluto is not sao Minh Vương but sao Diêm Vương "Yama star".[235]

References

- ^ a b c "IAU 2006 General Assembly: Result of the IAU Resolution votes". International Astronomical Union. 2006. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- ^ "Working Group on Extrasolar Planets (WGESP) of the International Astronomical Union". IAU. 2001. Archived from the original on 16 September 2006. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lakdawalla, Emily (21 April 2020). "What Is A Planet?". The Planetary Society. Archived from the original on 22 January 2022. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- ^ Grossman, Lisa (24 August 2021). "The definition of planet is still a sore point – especially among Pluto fans". Science News. Archived from the original on 10 July 2022. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- .

- S2CID 118522228.

- .

- S2CID 118572605.

- S2CID 18964068.

- Bibcode:2010exop.book..319D. Archivedfrom the original on 30 June 2015. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- Bibcode:2010exop.book..297C. Archivedfrom the original on 30 June 2015. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ISBN 978-0-8165-2844-8.

- S2CID 119216797.

- S2CID 4420518. Archived from the original(PDF) on 14 October 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- ^ Taylor, G. Jeffrey (31 December 1998). "Origin of the Earth and Moon". Planetary Science Research Discoveries. Hawai'i Institute of Geophysics and Planetology. Archived from the original on 10 June 2010. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- ^

Stern, S.A.; Bagenal, F.; Ennico, K.; Gladstone, G.R.; et al. (16 October 2015). "The Pluto system: Initial results from its exploration by New Horizons". Science. 350 (6258): aad1815. S2CID 1220226.

- Bibcode:1995PhDT..........D. Archived from the originalon 25 November 2007. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- S2CID 16301955.

- S2CID 15261426.

- ISSN 1745-3925.

- ISSN 0066-4146. Archived from the originalon 13 May 2022. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- .

- S2CID 21134564.

- ^ Chuang, F. (6 June 2012). "FAQ – Atmosphere". Planetary Science Institute. Archived from the original on 23 March 2022. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- doi:10.1086/428383.

- S2CID 118415186.

- ISBN 978-0-521-66148-5. Archivedfrom the original on 14 December 2023. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ "Planetary Physical Parameters". Solar System Dynamics. Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Archived from the original on 4 October 2022. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-12-446744-6.

- ^ a b Marley, Mark (2 April 2019). "Not a Heart of Ice". planetary.org. The Planetary Society. Archived from the original on 12 August 2019. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

- ^ S2CID 126574999. Archived from the originalon 7 April 2019.

- ^ arXiv:2309.15230 [astro-ph.EP].

- S2CID 21468196. Archived from the original(PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- ^ "How Big Is Pluto? New Horizons Settles Decades-Long Debate". NASA. 7 August 2017. Archived from the original on 9 November 2019. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

- ISBN 978-0-12-446744-6.

- ^ "Pre-generated Exoplanet Plots". exoplanetarchive.ipac.caltech.edu. NASA Exoplanet Archive. Archived from the original on 30 April 2012. Retrieved 24 June 2022.

- The Extrasolar Planets Encyclopedia. Retrieved 1 April 2024.

- S2CID 2614136.

- ^ S2CID 4260368.

- Bibcode:2008ASPC..398....3W. Archivedfrom the original on 13 May 2022. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ a b "What worlds are out there?". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 25 August 2016. Archived from the original on 25 August 2016. Retrieved 5 June 2017.

- ^ Chen, Rick (23 October 2018). "Top Science Results from the Kepler Mission". NASA. Archived from the original on 11 July 2022. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

The most common size of planet Kepler found doesn't exist in our solar system—a world between the size of Earth and Neptune—and we have much to learn about these planets.

- ^ from the original on 19 October 2022. Retrieved 11 July 2022.

- ^ Johnson, Michele (20 December 2011). "NASA Discovers First Earth-size Planets Beyond Our Solar System". NASA. Archived from the original on 16 May 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- S2CID 122575277.

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (20 December 2011). "Two Earth-Size Planets Are Discovered". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 December 2011. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- S2CID 119103101.

- ^ Watson, Traci (10 May 2016). "NASA discovery doubles the number of known planets". USA Today. Archived from the original on 10 May 2016. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ^ "The Habitable Exoplanets Catalog". Planetary Habitability Laboratory. University of Puerto Rico at Arecibo. Archived from the original on 20 October 2011. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ Sanders, R. (4 November 2013). "Astronomers answer key question: How common are habitable planets?". newscenter.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 7 November 2014. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

- PMID 24191033.

- ^ Drake, Frank (29 September 2003). "The Drake Equation Revisited". Astrobiology Magazine. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ S2CID 119114880.

- S2CID 2983930. Archived from the original(PDF) on 21 May 2009.

- ^ "New 'super-Earth' found in space". BBC News. 25 April 2007. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 25 April 2007.

- S2CID 14475537.

- ^ S2CID 119111221.

- S2CID 236464073.

- ^ "Extrasolar Planets". lasp.colorado.edu. Archived from the original on 5 April 2019. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- S2CID 53628741.

- ^ a b c d e Young, Charles Augustus (1902). Manual of Astronomy: A Text Book. Ginn & company. pp. 324–327.

- ISBN 978-3-540-28208-2.

- S2CID 16457143.

- ^ "Planets – Kuiper Belt Objects". The Astrophysics Spectator. 15 December 2004. Archived from the original on 23 March 2021. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- ^ Tatum, J. B. (2007). "17. Visual binary stars". Celestial Mechanics. Personal web page. Archived from the original on 6 July 2007. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- S2CID 11519263.

- .

- ^ a b Harvey, Samantha (1 May 2006). "Weather, Weather, Everywhere?". NASA. Archived from the original on 31 August 2006. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- ^ Planetary Fact Sheets, NASA

- .

- S2CID 119194526.

- .

- S2CID 7051928.

- ^ Seidelmann, P. Kenneth, ed. (1992). Explanatory Supplement to the Astronomical Almanac. University Science Books. p. 384.

- ISBN 978-1139494175. Archived from the originalon 1 January 2016.

- from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- S2CID 21133097.

- ^ Bibcode:1984NASCP2330..327B.

- ^ Borgia, Michael P. (2006). The Outer Worlds; Uranus, Neptune, Pluto, and Beyond. Springer New York. pp. 195–206.

- .

- ^ "Planet Compare". Solar System Exploration. NASA. Archived from the original on 9 March 2018. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- S2CID 16842429.

- S2CID 45608770.

- (PDF) from the original on 27 September 2019. Retrieved 9 September 2006.

- (PDF) from the original on 2 May 2019. Retrieved 9 September 2006.

- ISBN 978-0521455060. Archivedfrom the original on 6 August 2023. Retrieved 24 April 2017.

- ^ Young, Leslie A. (1997). "The Once and Future Pluto". Southwest Research Institute, Boulder, Colorado. Archived from the original on 30 March 2004. Retrieved 26 March 2007.

- S2CID 253522934.

- ^ . 193.

- ^

Rabinowitz, D. L.; Barkume, Kristina; Brown, Michael E.; Roe, Henry; Schwartz, Michael; Tourtellotte, Suzanne; Trujillo, Chad (2006). "Photometric Observations Constraining the Size, Shape, and Albedo of 2003 EL61, a Rapidly Rotating, Pluto-Sized Object in the Kuiper Belt". S2CID 11484750.

- Bibcode:2014arXiv1405.1025S.

- from the original on 25 February 2021. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- S2CID 16610947.

- ^ Milbert, D. G.; Smith, D. A. "Converting GPS Height into NAVD88 Elevation with the GEOID96 Geoid Height Model". National Geodetic Survey, NOAA. Archived from the original on 20 August 2011. Retrieved 7 March 2007.

- ^ Sandwell, D. T.; Smith, Walter H. F. (7 July 2006). "Exploring the Ocean Basins with Satellite Altimeter Data". NOAA/NGDC. Archived from the original on 15 July 2014. Retrieved 21 April 2007.

- ISBN 978-0-444-53803-1, archivedfrom the original on 13 May 2022, retrieved 13 May 2022

- ^ Brown, Michael E. (2006). "The Dwarf Planets". California Institute of Technology. Archived from the original on 16 January 2011. Retrieved 1 February 2008.

- ^ a b c d "Official Working Definition of an Exoplanet". IAU position statement. Archived from the original on 3 July 2022. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- ^ S2CID 118434022.

- ^ S2CID 51769219.

- S2CID 18649212.

- ISBN 978-0-19-064792-6. Archivedfrom the original on 6 June 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ S2CID 252992162.

- doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2010.01.025. Archived from the original(PDF) on 23 December 2018. Retrieved 7 May 2023.

- ^ Jia-Rui C. Cook and Dwayne Brown (26 April 2012). "Cassini Finds Saturn Moon Has Planet-Like Qualities". JPL/NASA. Archived from the original on 27 April 2012.

- .

- ^ Hardersen, Paul S.; Gaffey, Michael J. & Abell, Paul A. (2005). "Near-IR spectral evidence for the presence of iron-poor orthopyroxenes on the surfaces of six M-type asteroid". Icarus. 175 (1): 141. .

- ^ a b

Asphaug, E.; Reufer, A. (2014). "Mercury and other iron-rich planetary bodies as relics of inefficient accretion". Nature Geoscience. 7 (8): 564–568. doi:10.1038/NGEO2189.

- ^ S2CID 220546126

- ^ a b "Planetary Interiors". Department of Physics, University of Oregon. Archived from the original on 8 August 2012. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- ISBN 978-0-8160-5196-0.

- .

- (PDF) from the original on 22 August 2016. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- ^ "A look into Vesta's interior". Max-Planck-Gesellschaft. 6 January 2011. Archived from the original on 5 March 2023. Retrieved 7 May 2023.

- S2CID 206513512.

- ISBN 978-981-270-501-3. Archivedfrom the original on 14 December 2023. Retrieved 25 March 2010.

- ^ "Neptune: Moons: Triton". Solar System Exploration. Archived from the original on 10 January 2008. Retrieved 31 December 2007.

- S2CID 119194193.

- S2CID 18688556.

- ISBN 978-0-03-006228-5.

- ISBN 978-0123822253

- S2CID 250815558.

- S2CID 4201521.

- ISBN 978-3319195681. Archivedfrom the original on 21 August 2018. Retrieved 4 May 2023..

- S2CID 119482985.

- S2CID 4402268.

- "First Map of an Extrasolar Planet". Center for Astrophysics (Press release). 9 May 2007. Archived from the original on 5 December 2022. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- S2CID 701011.

- S2CID 4408861.

- S2CID 209324670.

- from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- Weaver, Donna; Villard, Ray (31 January 2007). "Hubble Probes Layer-cake Structure of Alien World's Atmosphere" (Press release). Space Telescope Science Institute. Archived from the original on 9 July 2016. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- from the original on 10 July 2022. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- S2CID 20549014.

- "NASA's Spitzer Sees Day and Night on Exotic World". NASA (Press release). 12 October 2006. Archived from the original on 13 July 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2007.

- from the original on 14 December 2023. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- from the original on 14 December 2023. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-12-088589-3.

- from the original on 25 April 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ Gefter, Amanda (17 January 2004). "Magnetic planet". Astronomy. Archived from the original on 1 June 2019. Retrieved 29 January 2008.

- from the original on 10 July 2022. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- .

- .

- ^ Jones, Nicola (11 December 2001). "Bacterial explanation for Europa's rosy glow". New Scientist Print Edition. Archived from the original on 10 April 2008. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- PMID 29487311.

- from the original on 7 July 2021. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- Bibcode:1996DPS....28.1815M.

- ISBN 978-3-540-00241-3.

- (PDF) from the original on 7 November 2020. Retrieved 6 October 2022.

- Wikidata Q116754015.

- S2CID 11685964.

- Whitney Clavin (29 November 2005). "A Planet With Planets? Spitzer Finds Cosmic Oddball". NASA (Press release). Archived from the original on 11 October 2012. Retrieved 10 September 2007.

- S2CID 118456052.

- ^ "What is a Planet? | Planets". NASA Solar System Exploration. Archived from the original on 26 April 2022. Retrieved 2 May 2022.

- ^ a b c Hilton, James L. (17 September 2001). "When Did the Asteroids Become Minor Planets?". U.S. Naval Observatory. Archived from the original on 21 September 2007. Retrieved 8 April 2007.

- ^ from the original on 11 September 2022. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- The Library of Congress. Archivedfrom the original on 1 May 2015. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- Perseus ProjectRetrieved on 11 July 2022.

- ^ "Definition of planet". Merriam-Webster OnLine. Archived from the original on 1 June 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2007.

- ^ "Planet Etymology". dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 2 July 2015. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ a b "planet, n". Oxford English Dictionary. 2007. Archived from the original on 3 July 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2008. Note: select the Etymology tab

- S2CID 162347339.

- ^ Ronan, Colin (1996). "Astronomy Before the Telescope". In Walker, Christopher (ed.). Astronomy in China, Korea and Japan. British Museum Press. pp. 264–265.

- ISBN 978-0-674-17103-9.

- ^ OCLC 227002144.

- ^ a b c d e

Evans, James (1998). The History and Practice of Ancient Astronomy. Oxford University Press. pp. 296–297. ISBN 978-0-19-509539-5. Retrieved 4 February 2008.

- ^ Rochberg, Francesca (2000). "Astronomy and Calendars in Ancient Mesopotamia". In Jack Sasson (ed.). Civilizations of the Ancient Near East. Vol. III. p. 1930.

- ISBN 978-0521227179

- ISBN 978-951-570-130-5.

- JSTOR 602955.

- (PDF) from the original on 4 February 2019. Retrieved 6 February 2008.

- S2CID 121539390.

- ISBN 978-1-4067-6601-1. Retrieved 7 February 2008.

- from the original on 24 December 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2022.

The Greeks, for example, originally identified the morning and evening stars with two separate deities, Phosphoros and Hesporos respectively. In Mesopotamia, it seems that this was recognized prehistorically. Assuming its authenticity, a cylinder seal from the Erlenmeyer collection attests to this knowledge in southern Iraq as early as the Late Uruk / Jemdet Nasr Period, as do the archaic texts of the period. [...] Whether or not one accepts the seal as authentic, the fact that there is no epithetical distinction between the morning and evening appearances of Venus in any later Mesopotamian literature attests to a very, very early recognition of the phenomenon.

- from the original on 16 June 2022. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ S2CID 118875902.

- ISBN 978-0-691-00260-6.

- MacTutor History of Mathematics archive. Archivedfrom the original on 1 February 2022. Retrieved 10 July 2022.

- ISBN 0-7923-4066-3.

- ^ Bausani, Alessandro (1973). "Cosmology and Religion in Islam". Scientia/Rivista di Scienza. 108 (67): 762.

- ISBN 978-0-333-75088-9.

- ISBN 978-0-674-07282-4.

- ^ a b Van Helden, Al (1995). "Copernican System". The Galileo Project. Rice University. Archived from the original on 19 July 2012. Retrieved 28 January 2008.

- Dreyer, J. L. E. (1912). The Scientific Papers of Sir William Herschel. Vol. 1. Royal Society and Royal Astronomical Society. p. 100.

- ^ "asteroid". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ S2CID 119206487.

- ISBN 978-0738208893.

- S2CID 125439949.

- ISBN 978-0-684-83252-4.

- .

- PMID 16591209.

- S2CID 120501620.

- .

- ^ British Broadcasting Corporation. 24 August 2006. Archivedfrom the original on 30 May 2012. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- ^ Hind, John Russell (1863). An introduction to astronomy, to which is added an astronomical vocabulary. London: Henry G. Bohn. p. 204. Archived from the original on 30 October 2023. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- ^ Hunter, Robert; Williams, John A.; Heritage, S. J., eds. (1897). The American Encyclopædic Dictionary. Vol. 8. Chicago and New York: R. S. Peale and J. A. Hill. pp. 3553–3554. Archived from the original on 30 October 2023. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 4 July 2008. Retrieved 4 August 2008.

- ABC (in Spanish). 20 September 2008. Archivedfrom the original on 6 October 2017. Retrieved 18 September 2008.

- ^ Brown, Michael E. "The Dwarf Planets". California Institute of Technology, Department of Geological Sciences. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 26 January 2008.

- ^ Brown, Mike (23 February 2021). "How Many Dwarf Planets Are There in the Outer Solar System?". California Institute of Technology. Archived from the original on 19 July 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- British Broadcasting Corporation. Archivedfrom the original on 2 March 2007. Retrieved 23 August 2008.

- Bibcode:2006IAUC.8747....1G. Circular No. 8747. Archived from the originalon 24 June 2008. Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- ISBN 978-1-58381-086-6See p. 208.

- ^ Runyon, Kirby D.; Stern, S. Alan (17 May 2018). "An organically grown planet definition — Should we really define a word by voting?". Astronomy. Archived from the original on 10 October 2019. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- ^ Sean Solomon, Larry Nittler & Brian Anderson, eds. (2018) Mercury: The View after MESSENGER. Cambridge Planetary Science series no. 21, Cambridge University Press, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Brown, Mike [@plutokiller] (10 February 2023). "The real answer here is to not get too hung up on definitions, which I admit is hard when the IAU tries to make them sound official and clear, but, really, we all understand the intent of the hydrostatic equilibrium point, and the intent is clearly to include Merucry & the moon" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- from the original on 21 June 2022. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- ISSN 0035-8711.

- ^ Villard, Ray (14 May 2010). "Should Large Moons Be Called 'Satellite Planets'?". Discovery News. Discovery, Inc. Archived from the original on 5 May 2012. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ^ Urrutia, Doris Elin (28 October 2019). "Asteroid Hygiea May be the Smallest Dwarf Planet in the Solar System". Space.com. Purch Group. Archived from the original on 5 November 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ "The solar system may have a new smallest dwarf planet: Hygiea". Science News. Society for Science. 28 October 2019. Archived from the original on 31 August 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^ Netburn, Deborah (13 November 2015). "Why we need a new definition of the word 'planet'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 3 June 2021. Retrieved 24 July 2016.

- ^ a b

S2CID 51684830.

- Bibcode:2003IAUS..211..529B

- S2CID 4339201.

- .

- from the original on 13 May 2022. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ S2CID 247065421.

- S2CID 118553341.

- S2CID 118513110.

- S2CID 55994657.

- ^ Exoplanet Criteria for Inclusion in the Archive Archived 27 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine, NASA Exoplanet Archive

- S2CID 191393468.

- ^ Wiggermann, Frans A. M. (1998). "Nergal A. Philological". Reallexikon der Assyriologie. Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities. Archived from the original on 6 June 2021. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ISBN 978-87-7289-287-0.

- from the original on 22 March 2022. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ Rengel, Marian; Daly, Kathleen N. (2009). Greek and Roman Mythology, A to Z Archived 29 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine. United States: Facts On File, Incorporated. p. 66.

- ^

Zerubavel, Eviatar (1989). The Seven Day Circle: The history and meaning of the week. University of Chicago Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-226-98165-9. Retrieved 7 February 2008.

- ^ a b

Falk, Michael; Koresko, Christopher (2004). "Astronomical names for the days of the week". S2CID 118954190.

- ^ Ross, Margaret Clunies (January 2018). "Explainer: the gods behind the days of the week". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 13 May 2022. Retrieved 13 May 2022.

- ^ "earth". Oxford English Dictionary. Archived from the original on 10 May 2021. Retrieved 7 May 2021.

- ^ Harper, Douglas (September 2001). "Etymology of "terrain"". Online Etymology Dictionary. Archived from the original on 23 August 2012. Retrieved 30 January 2008.

- ISBN 978-0781810029.

- ^ Markel, Stephen Allen (1989). The Origin and Early Development of the Nine Planetary Deities (Navagraha) (PhD). University of Michigan. Archived from the original on 13 May 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- ^ Panaino, Antonio (20 September 2016). "Planets". Encyclopædia Iranica. Archived from the original on 24 February 2023. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2022. Retrieved 21 September 2022.

- ^ "Planetary linguistics". nineplanets.org. Archived from the original on 7 April 2010. Retrieved 8 April 2010.

- ^ "Cambridge English-Vietnamese Dictionary". Archived from the original on 7 October 2022. Retrieved 21 September 2022.

- from the original on 5 May 2023. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ a b

Stieglitz, Robert (April 1981). "The Hebrew names of the seven planets". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 40 (2): 135–137. S2CID 162579411.

- ^ Ettinger, Yair (31 December 2009). "Uranus and Neptune Get Hebrew Names at Last". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 5 October 2022. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- S2CID 162671357.

- ^ Ragep, F.J.; Hartner, W. (24 April 2012). "Zuhara". Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.). Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 16 January 2019 – via referenceworks.brillonline.com.

- ^

Meyers, Carol L.; O'Connor, M.; O'Connor, Michael Patrick (1983). The Word of the Lord Shall Go Forth: Essays in honor of David Noel Freedman in celebration of his sixtieth birthday. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-0931464195– via Google Books.

- ^ Eilers, Wilhelm (1976). Sinn und Herkunft der Planetennamen (PDF). Munich: Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2022. Retrieved 28 August 2022.

- ^

Galter, Hannes D. (23–27 September 1991). "Die Rolle der Astronomie in den Kulturen Mesopotamiens" [The role of astronomy in the cultures of the Mesopotamians]. Beiträge Zum 3. Grazer Morgenländischen Symposion (23–27 September 1991). 3. Grazer Morgenländischen Symposion [Third Graz Oriental Symposium]. Graz, Austria: GrazKult (published 31 July 1993). ISBN 978-3853750094– via Google Books.

- ^ al-Masūdī (1841). "El-Masūdī's Historical Encyclopaedia, entitled "Meadows of Gold and Mines of Gems."". Oriental Translation Fund of Great Britain and Ireland – via Google Books.

- ^ Ali-Abu'l-Hassan, Mas'ûdi (1841). "Historical Encyclopaedia: Entitled "Meadows of gold and mines of gems"". Printed for the Oriental Translation Fund of Great Britain and Ireland – via Google Books.

- ISBN 978-3642297182.

- ^ "Minor Planet Naming Guidelines (Rules and Guidelines for naming non-cometary small Solar-System bodies) – v1.0" (PDF). Working Group Small Body Nomenclature (PDF). 20 December 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 March 2023. Retrieved 1 May 2022.

- ^ "IAU: WG Small Body Nomenclature (WGSBN)". Working Group Small Body Nomenclature. Archived from the original on 8 February 2022. Retrieved 9 February 2022.

- ^

Lassell, W. (1852). "Beobachtungen der Uranus-Satelliten". Astronomische Nachrichten. 34: 325. Bibcode:1852AN.....34..325.

- ^ "Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature". IAU. Archived from the original on 21 August 2014. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-87169-233-7.

- ^ "Bianchini's planisphere". Florence, Italy: Istituto e Museo di Storia della Scienza [Institute and Museum of the History of Science]. Archived from the original on 27 February 2018. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ^ a b

Maunder, A.S.D. (1934). "The origin of the symbols of the planets". The Observatory. Vol. 57. pp. 238–247. Bibcode:1934Obs....57..238M.

- ^ Mattison, Hiram (1872). High-School Astronomy. Sheldon & Co. pp. 32–36.

- ^ a b Iancu, Laurentiu (14 August 2009). "Proposal to Encode the Astronomical Symbol for Uranus" (PDF). unicode.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 October 2022. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- Bibcode:1784vdne.book.....B.

- ^ a b Gould, B.A. (1850). Report on the history of the discovery of Neptune. Smithsonian Institution. pp. 5, 22.

- Bibcode:1917Obs....40..306H.

- ^ "NASA's Solar System Exploration: Multimedia: Gallery: Pluto's Symbol". NASA. Archived from the original on 1 October 2006. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ a b c d Miller, Kirk (26 October 2021). "Unicode request for dwarf-planet symbols" (PDF). unicode.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 March 2022. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- ^ The IAU Style Manual (PDF). 1989. p. 27. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- ^ Anderson, Deborah (4 May 2022). "Out of this World: New Astronomy Symbols Approved for the Unicode Standard". unicode.org. The Unicode Consortium. Archived from the original on 6 August 2022. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

External links

- Photojournal NASA

- Planetary Science Research Discoveries (educational site with illustrated articles)