Pliocene

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2019) |

| Pliocene | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chronology | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

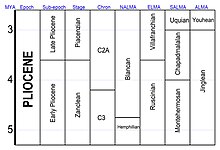

The Pliocene ( As with other older geologic periods, the geological strata that define the start and end are well-identified but the exact dates of the start and end of the epoch are slightly uncertain. The boundaries defining the Pliocene are not set at an easily identified worldwide event but rather at regional boundaries between the warmer Miocene and the relatively cooler Pleistocene. The upper boundary was set at the start of the Pleistocene glaciations. EtymologyCharles Lyell (later Sir Charles) gave the Pliocene its name in Principles of Geology (volume 3, 1833).[11] The word pliocene comes from the Greek words πλεῖον (pleion, "more") and καινός (kainos, "new" or "recent") Subdivisions In the official timescale of the ICS, the Pliocene is subdivided into two stages. From youngest to oldest they are:

The Piacenzian is sometimes referred to as the Late Pliocene, whereas the Zanclean is referred to as the Early Pliocene. In the system of

In the Paratethys area (central Europe and parts of western Asia) the Pliocene contains the Dacian (roughly equal to the Zanclean) and Romanian (roughly equal to the Piacenzian and Gelasian together) stages. As usual in stratigraphy, there are many other regional and local subdivisions in use. In Praetiglian, Tiglian A, Tiglian B, Tiglian C1-4b, Tiglian C4c, Tiglian C5, Tiglian C6 and Eburonian. The exact correlations between these local stages and the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS) stages is still a matter of detail.[18]

Climate The beginning of the Pliocene was marked by an increase in global temperatures relative to the cooler Messinian related to the 1.2 million year obliquity amplitude modulation cycle.[19] The global average temperature in the mid-Pliocene (3.3–3 mya) was 2–3 °C higher than today,[20] carbon dioxide levels were the same as today (400 ppm),[21] and global sea level was 25 m higher.[22] The northern hemisphere ice sheet was ephemeral before the onset of extensive glaciation over Greenland that occurred in the late Pliocene around 3 Ma.[23] The formation of an Arctic North Pacific Ocean beds.[24] Mid-latitude glaciation was probably underway before the end of the epoch. The global cooling that occurred during the Pliocene may have accelerated on the disappearance of forests and the spread of grasslands and savannas.[25]

Paleogeography Continents continued to native ungulate fauna,[26] though other South American lineages like its predatory mammals were already extinct by this point and others like xenarthrans continued to do well afterwards. The formation of the Isthmus had major consequences on global temperatures, since warm equatorial ocean currents were cut off and an Atlantic cooling cycle began, with cold Arctic and Antarctic waters dropping temperatures in the now-isolated Atlantic Ocean.[27]

Africa's collision with Europe formed the Mediterranean Sea, cutting off the remnants of the Tethys Ocean. The border between the Miocene and the Pliocene is also the time of the Messinian salinity crisis.[28][29] During the Late Pliocene, the Himalayas became less active in their uplift, as evidenced by sedimentation changes in the Bengal Fan.[30] The land bridge between Alaska and Siberia (Beringia) was first flooded near the start of the Pliocene, allowing marine organisms to spread between the Arctic and Pacific Oceans. The bridge would continue to be periodically flooded and restored thereafter.[31] Pliocene marine formations are exposed in northeast Spain,[32] southern California,[33] New Zealand,[34] and Italy.[35] During the Pliocene parts of southern Norway and southern Sweden that had been near sea level rose. In Norway this rise elevated the Hardangervidda plateau to 1200 m in the Early Pliocene.[36] In Southern Sweden similar movements elevated the South Swedish highlands leading to a deflection of the ancient Eridanos river from its original path across south-central Sweden into a course south of Sweden.[37] Environment and evolution of human ancestorsThe Pliocene is bookended by two significant events in the evolution of human ancestors. The first is the appearance of the modern humans and their closest extinct relatives, near the end of the Pliocene at 2.6 million years ago.[41] Key traits that evolved among hominins during the Pliocene include terrestrial bipedality and, by the end of the Pliocene, encephalized brains (brains with a large neocortex relative to body mass[42][a] and stone tool manufacture.[43]

Improvements in Sherwood L. Washburn, emphasized an intrinsic model of hominin evolution. According to this model, early evolutionary developments triggered later developments. The model placed little emphasis on the surrounding environment.[46] Anthropologists tended to focus on intrinsic models while geologists and vertebrate paleontologists tended to put greater emphasis on habitats.[47]

Alternatives to the savanna hypothesis include the woodland/forest hypothesis, which emphasizes the evolution of hominins in closed habitats, or hypotheses emphasizing the influence of colder habitats at higher latitudes or the influence of seasonal variation. More recent research has emphasized the variability selection hypothesis, which proposes that variability in climate fostered development of hominin traits.[43] Improved climate proxies show that the Pliocene climate of east Africa was highly variable, suggesting that adaptability to varying conditions was more important in driving hominin evolution than the steady pressure of a particular habitat.[42] FloraThe change to a cooler, drier, more seasonal climate had considerable impacts on Pliocene vegetation, reducing tropical species worldwide. deserts appeared in Asia and Africa.[48][failed verification ]

FaunaBoth marine and continental faunas were essentially modern, although continental faunas were a bit more primitive than today. The land mass collisions meant great migration and mixing of previously isolated species, such as in the Herbivores got bigger, as did specialized predators.

Image gallery

Mammals

In North America, carnivores including the weasel family diversified, and dogs and short-faced bears did well. Ground sloths, huge glyptodonts, and armadillos came north with the formation of the Isthmus of Panama.

In saber-toothed cats appeared, joining other predators including dogs, bears and weasels.

Africa was dominated by hoofed animals, and primates continued their evolution, with australopithecines (some of the first hominins) and baboon-like monkeys such as the Dinopithecus appearing in the late Pliocene. Rodents were successful, and elephant populations increased. Cows and antelopes continued diversification and overtook pigs in numbers of species. Early giraffes appeared. Horses and modern rhinos came onto the scene. Bears, dogs and weasels (originally from North America) joined cats, hyenas and civets as the African predators, forcing hyenas to adapt as specialized scavengers. Most mustelids in Africa declined as a result of increased competition from the new predators, although Enhydriodon omoensis remained an unusually successful terrestrial predator. South America was invaded by North American species for the first time since the armadillos did the opposite, migrating to the north and thriving there.

The marsupials remained the dominant Australian mammals, with herbivore forms including dasyurids, the dog-like thylacine and cat-like Thylacoleo. The first rodents arrived in Australia. The modern platypus, a monotreme , appeared.

Birds The predatory South American Struthio and Corvus ), some now extinct.

Reptiles and amphibiansAlligator mississippiensis, having evolved in the Miocene, continued into the Pliocene, except with a more northern range; specimens have been found in very late Miocene deposits of Tennessee. Giant tortoises still thrived in North America, with genera like Hesperotestudo. Madtsoid snakes were still present in Australia. The amphibian order Allocaudata became extinct.

CoralsThe Pliocene was a high water mark for species diversity among Caribbean corals. From 5 to 2 Ma, coral species origination rates were relatively high in the Caribbean, although a noticeable extinction event and drop in diversity occurred at the end of this interval.[50] Oceans

Oceans continued to be relatively warm during the Pliocene, though they continued cooling. The Arctic ice cap formed, drying the climate and increasing cool shallow currents in the North Atlantic. Deep cold currents flowed from the Antarctic. The formation of the Isthmus of Panama about 3.5 million years ago[51] cut off the final remnant of what was once essentially a circum-equatorial current that had existed since the Cretaceous and the early Cenozoic. This may have contributed to further cooling of the oceans worldwide. The Pliocene seas were alive with sea cows, seals, sea lions and sharks. See also

Notes

References

Further reading

External linksWikimedia Commons has media related to Pliocene. Wikisource has original works on the topic: Cenozoic#Neogene

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||