Cipher Bureau (Poland)

| Methods and technology |

|---|

| Locations |

| Personnel |

|

Chief

Gwido Langer German Section cryptologists Wiktor Michałowski

Chief of Russian Section

Jan Graliński Russian Section cryptologist

Piotr Smoleński |

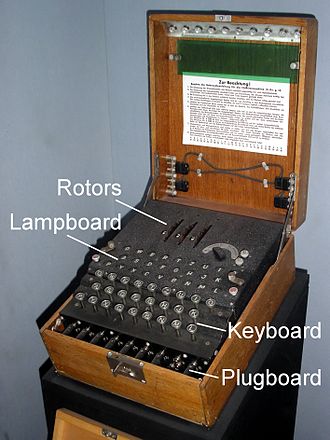

| The Enigma cipher machine |

|---|

| Enigma machine |

| Breaking Enigma |

| Related |

The Cipher Bureau (

(the study of ciphers and codes, for the purpose of "breaking" them).The precursor of the agency that would become the Cipher Bureau was created in May 1919, during the

In mid-1931, the Cipher Bureau was formed by the merger of pre-existing agencies. In December 1932, the Bureau began breaking Germany's Enigma ciphers. Over the next seven years, Polish cryptologists overcame the growing structural and operating complexities of the plugboard-equipped Enigma. The Bureau also broke Soviet cryptography.

Five weeks before the outbreak of

Background

On 8 May 1919 Lt.

During the

The Soviet staffs, according to Polish Colonel Mieczysław Ścieżyński,

had not the slightest hesitation about sending any and all messages of an operational nature by means of radiotelegraphy; there were periods during the war when, for purposes of operational communications and for purposes of command by higher staffs, no other means of communication whatever were used, messages being transmitted either entirely "in clear" (plaintext) or encrypted by means of such an incredibly uncomplicated system that for our trained specialists reading the messages was child's play. The same held for the chitchat of personnel at radiotelegraphic stations, where discipline was disastrously lax.[6]

In the crucial month of August 1920 alone, Polish cryptologists

- from Soviet General Mikhail Tukhachevsky, commander of the northern front

- from Leon Trotsky, Soviet commissar of war

- from commanders of armies, for example:

- the commander of the RKKA IV Army, Yevgenii Nikolaievich Sergeev

- the commander of the Semyon Budionny

- the commander of the Gai

- from the staffs of the XII, XV and XVI Armies

- from the staffs of:

- the Mozyr Group (named after the Belarusiancity)

- the Zolochiv Group (after the Ukrainian town)

- the Yakir Group [after General Iona Emmanuilovich Yakir]

- the

- from the 2, 4, 7, 10, 11, 12, 16, 17, 18, 24, 27, 41, 44, 45, 53, 54, 58 and 60 Infantry Divisions

- from the 8 Cavalry Division

etc.[7]

The intercepts were as a rule

The intercepts even included an order from

Ścieżyński surmises that the Soviets must likewise have intercepted Polish operational signals; but he doubts that this would have availed them much, since Polish cryptography "stood abreast of modern cryptography" and since only a small number of Polish higher headquarters were equipped with

Polish cryptologists enjoyed generous support under the command of Col.

The discovery of the Cipher Bureau's archives, decades after the

that ... radio intelligence ... furnished [the Polish Commander-in-Chief,

Cipher Bureau

In mid-1931, at the Polish

Between 1932 and 1936, the Cipher Bureau took on additional responsibilities, including radio communications between military intelligence posts in Poland and abroad, as well as radio counterintelligence – mobile direction-finding and intercept stations for the locating and traffic analysis of spy and fifth column transmitters operating in Poland.[12]

Stalking Enigma

In late 1927 or early 1928, there arrived at the Warsaw Customs Office from Germany a package that, according to the accompanying declaration, was supposed to contain radio equipment. The German firm's representative strenuously demanded that the package be returned to Germany even before going through customs, as it had been shipped with other equipment by mistake. His insistent demands alerted the customs officials, who notified the Polish General Staff's Cipher Bureau, which took a keen interest in new developments in radio technology. Since it happened to be a Saturday afternoon, the Bureau's experts had ample time to look into the matter. They carefully opened the box and found that it did not, in fact, contain radio equipment but a cipher machine. They examined the machine minutely, then put it back into the box.[14]

The Bureau's leading Enigma cryptanalyst Marian Rejewski commented that the cipher machine may be surmised to have been a commercial-model Enigma since at that time the military model had not yet been devised. "Hence this trivial episode was of no practical importance, though it does fix the date at which the Cipher Bureau's interest in the Enigma machine began" – manifested, initially, in the entirely legal acquisition of a single commercial-model Enigma.[14]

On 15 July 1928, the first German machine-enciphered messages were broadcast by German military radio stations. Polish monitoring stations began intercepting them, and cryptologists in the Polish Cipher Bureau's German section were instructed to try to read them. The effort was fruitless, however, and was eventually abandoned. There remained very slight evidence of the effort, in the form of a few densely written-over sheets of paper and the commercial-model Enigma machine.

In 1929, while the Cipher Bureau's predecessor agency was still headed by Major Franciszek Pokorny (a relative of the outstanding

In September 1932, Maksymilian Ciężki hired three young graduates of the Poznań course to be Bureau staff members: Marian Rejewski, Jerzy Różycki and Henryk Zygalski.[15]

Successes and setbacks

In 1926, the German Navy adopted, as its top cryptographic device, a modified civilian Enigma machine; in 1928 the German Army followed suit.[16] The complexity of the system was much increased in 1930 by the introduction of a plugboard (Steckerbrett), albeit with only six connecting leads in use.[17] In December 1932, Marian Rejewski made what historian David Kahn describes as one of the greatest advances in cryptologic history, by applying pure mathematics – the theory of permutations and groups – to breaking the German armed forces' Enigma machine ciphers.[18][19] Rejewski had worked out the precise interconnections of the Enigma rotors and reflector, after the Bureau had received, from French Military Intelligence Captain Gustave Bertrand, two German documents and two pages of Enigma daily keys (for September and October of that year).[20] These had been obtained by a French military intelligence agent, a German codenamed Rex,[a] from an agent who worked at Germany's Cipher Office in Berlin, Hans-Thilo Schmidt, whom the French codenamed Asché. [b][21]

After Rejewski had worked out the military Enigma's logical structure, the Polish Cipher Bureau commissioned the

The Germans increased the difficulty of decrypting Enigma messages by decreasing the interval between changes in the order of the rotors from quarterly, initially, to monthly in February 1936, then daily in October of that year, when they also increased the number of plugboard leads from six to a number that varied between five and eight. This made the Biuro's grill method much less easy,[25] as it relied on 'unsteckered' letter pairs.[26] The German navy was more security-conscious than the army and air force, and in May 1937 it introduced a new, much more secure, indicator procedure that remained unbroken for several years.[27]

The next setback occurred in November 1937, when the scrambler's reflector was changed to one with different interconnections (known as Umkehrwalze-B). Rejewski worked out the wiring in the new reflector, but the catalogue of characteristics had to be compiled anew, again using Rejewski's "cyclometer", which had been built to his specifications by the AVA Radio Company.[28]

In January 1938, Colonel Stefan Mayer directed that statistics be compiled for a two-week period, comparing the numbers of Enigma messages solved, to Enigma intercepts. The ratio came to 75 percent. "Nor", Marian Rejewski has commented, "were those 75 percent ... the limit of our possibilities. With slightly augmented personnel, we might have attained about 90 percent ... read. But a certain amount of cipher material ... due to faulty transmission or ... reception, or to various other causes, always remains unread".[29] Information obtained from Enigma decryption seems to have been directed from B.S.-4 principally to the German Office of the General Staff's Section II (Intelligence). There, from fall 1935 to mid-April 1939, it was worked up by Major Jan Leśniak, who in April 1939 would turn the German Office over to another officer and himself form a Situation Office intended for wartime service. He would head the Situation Office to and through the September 1939 Campaign.[30]

The system of pre-defining the indicator setting for the day for all Enigma operators on a given network, on which the method of characteristics depended, was changed on 15 September 1938. The one exception to this was the network used by the Sicherheitsdienst (SD)—the intelligence agency of the SS and the Nazi Party—who did not make the change until 1 July 1939. Operators now chose their own indicator setting. However, the insecure procedure of sending the enciphered message key twice remained in use, and it was quickly exploited. Henryk Zygalski devised a manual method that used 26 perforated sheets, and Marian Rejewski commissioned the AVA company to produce the bomba kryptologiczna (cryptologic bomb).[31]

Both the Zygalski-sheet method and each bomba worked for only a single scrambler rotor order, so six sets of Zygalski sheets and six bomby were produced.[32] However, the Germans introduced two new rotors on 15 December 1938, giving a choice of three out of five to assemble in the machines on a given day.[33] This increased the number of possible rotor orders from 6 to 60. The Biuro could then only read the small minority of messages that used neither of the two new rotors. They did not have the resources to produce 54 more bomby or 54 sets of Zygalski sheets. Fortunately, however, the fact that the SD network was still using the old method of the same indicator setting for all messages, allowed Rejewski to re-use his previous method of working out the wiring within these rotors.[34] This information was essential for the production of a full set Zygalski sheets which allowed resumption of large-scale decryption in January 1940. On 1 January 1939, the Germans made military Enigma even more difficult to break by increasing the number of plugboard connections from between five and eight, to between seven and ten.[26]

When

Kabaty Woods

| The Enigma cipher machine |

|---|

| Enigma machine |

| Breaking Enigma |

| Related |

Until 1937 the Cipher Bureau's German section, BS-4, had been housed in the Polish General Staff building – the stately 18th-century "

The move was dictated as well by requirements of security. Germany's Abwehr was always looking for potential traitors among the military and civilian workers at the General Staff building. Strolling agents, even if lacking access to the Staff building, could observe personnel entering and leaving, and photograph them with concealed miniature cameras. Annual Abwehr intelligence assignments for German agents in Warsaw placed a priority on securing informants at the Polish General Staff.[36]

Gift to allies

It was in the Kabaty Woods, at Pyry, on 25 and 26

When Rejewski had been working on reconstructing the German military Enigma machine in late 1932, he had ultimately solved a crucial element, the wiring of the letters of the alphabet into the entry drum, with the inspired guess that they might be wired in simple alphabetical order. Now, at the trilateral meeting – Rejewski was later to recount – "the first question that ...

The Poles' gift, to their western Allies, of Enigma decryption, five weeks before the outbreak of World War II, came not a moment too soon. Former Bletchley Park mathematician-cryptologist Gordon Welchman later wrote: "Ultra would never have gotten off the ground if we had not learned from the Poles, in the nick of time, the details both of the German military ... Enigma machine, and of the operating procedures that were in use."[42] Allied Supreme Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower, at war's end, described intelligence from Bletchley Park as having been "of priceless value to me. It has simplified my task as a commander enormously." Eisenhower expressed his thanks for this "decisive contribution to the Allied war effort".[43]

British prime minister Winston Churchill's greatest wartime fear, even after Hitler had suspended Operation Sea Lion and invaded the Soviet Union, was that the German submarine wolfpacks would succeed in strangling sea-locked Britain.[44] A major factor that averted Britain's defeat in the Battle of the Atlantic was her regained mastery of Naval Enigma decryption; and while the latter benefited crucially from British seizure of German Enigma-equipped naval vessels, the breaking of German naval signals ultimately relied on techniques that had been pioneered by the Polish Cipher Bureau.[45] Had Britain capitulated to Hitler, the United States would have been deprived of an essential forward base for its subsequent involvement in the European and North African theaters.[46]

A week after the Pyry meeting,

On 5 September 1939, as it became clear that Poland was unlikely to halt the ongoing German invasion, BS-4 received orders to destroy part of its files and evacuate essential personnel.[48]

Bureau abroad

During the German

In the interest of security, the Allied cryptological services, before sending their messages over a

In January 1940, the British cryptanalyst

During this period, until the collapse of France in June 1940, ultimately 83 percent of the Enigma keys that were found, were solved at Bletchley Park, the remaining 17 percent at PC Bruno. Rejewski commented:

How could it be otherwise, when there were three of us [Polish cryptologists] and [there were] at least several hundred British cryptologists, since about 10,000 people worked in Bletchley ... Besides, recovery of keys also depended on the amount of intercepted cipher material, and that amount was far greater on the British side than on the French side. Finally, in France (by contrast with the work in Poland) we ourselves not only sought for the daily keys, but after finding the key also read the messages. ... One can only be surprised that the Poles had as many as 17 percent of the keys to their credit.[55][56][e]

The inter-Allied cryptologic collaboration prevented duplication of effort and facilitated discoveries. Before fighting had started in Norway in April 1940, the Polish-French team solved an uncommonly hard three-letter code used by the Germans to communicate with fighter and bomber squadrons and for exchange of meteorological data between aircraft and land.[57] The code had first appeared in December 1939, but the Polish cryptologists had been too preoccupied with Enigma to give the code much attention.[57] With the German assault on the west impending, however, the breaking of the Luftwaffe code took on mounting urgency. The trail of the elusive code (whose system of letters changed every 24 hours) led back to Enigma. The first clue came from the British, who had noticed that the code's letters did not change randomly. If A changed to P, then elsewhere P was replaced by A. The British made no further headway, but the Poles realized that what was manifesting was Enigma's exclusivity principle that they had discovered in 1932. The Germans' carelessness meant that now the Poles, having after midnight solved Enigma's daily setting, could with no further effort also read the Luftwaffe signals.[58][f]

The Germans, just before opening their 10 May 1940 offensive in the west that would trample Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands in order to reach the borders of France, once again changed their procedure for enciphering message keys, rendering the Zygalski sheets "completely useless"[59][60] and temporarily defeating the joint British–Polish cryptologic attacks on Enigma. According to Gustave Bertrand, "It took superhuman day-and-night effort to overcome this new difficulty: on May 20, decryption resumed."[61][g]

Following the capitulation of France in June 1940, the Poles were evacuated to Algeria. On October 1, 1940, they resumed work at Cadix, near Uzès in unoccupied southern Vichy France, under the sponsorship of Gustave Bertrand.[62]

A little over two years later, on 8 November 1942, Bertrand learned from the BBC that the Allies had landed in French North Africa ("Operation Torch"). Knowing that in such an eventuality the Germans planned to occupy Vichy France, on 9 November he evacuated Cadix. Two days later, on 11 November, the Germans indeed marched into southern France. On the morning of 12 November they occupied Cadix.[63]

Over the two years since its establishment in October 1940, Cadix had decrypted thousands of

Having departed Cadix, the Polish personnel evaded the occupying Italian security police and German Gestapo and sought to escape France via Spain.[66] Jerzy Różycki, Jan Graliński and Piotr Smoleński had died in the January 1942 sinking, in the Mediterranean Sea, of a French passenger ship, the Lamoricière, in which they had been returning to southern France from a tour of duty in Algeria.[i][67]

Finally, with the end of the two mathematicians' cryptologic work at the close of World War II, the Cipher Bureau ceased to exist. From nearly its inception in 1931 until war's end in 1945, the Bureau, sometimes incorporated into aggregates under

Secret preserved

Despite their travails, Rejewski and Zygalski had fared better than some of their colleagues. Cadix's Polish military chiefs,

Before the war,

In popular culture

In 1967 the Polish military historian Władysław Kozaczuk, in his book Bitwa o tajemnice (The Battle for Secrets), first revealed that the German Enigma had been broken by Polish cryptologists before World War II. Kozaczuk's disclosure came seven years before F. W. Winterbotham's The Ultra Secret (1974) changed conventional views of the history of the war.[79]

The 1979 Polish film

See also

- Ultra

- Marian Rejewski

- Tadeusz Pełczyński

- Polish School of Mathematics

- History of Polish Intelligence Services

- Wilfred Dunderdale

Notes

- ^ Rex had been born Rudolf Stallmann in Berlin in 1871 and had changed his surname to that of his French wife, becoming "Rodolphe Lemoine". Kahn 1991, p. 57.

- ^ The documents were entitled Gebrauchsanweisung für die Chiffriermaschine Enigma (Instructions for Using the Enigma Cipher Machine) and Schlüsselanleitung für die Chiffriermaschine Enigma (Keying Instructions for the Enigma Cipher Machine).

- ^ These were that the indicator setting was defined for the day on the key-setting sheets and that the 3-letter indicator was sent twice as six letters of ciphertext.

- Pyry (or Kabaty Woods) meeting took place on only one day, 25 July.

- ^ Actually, at this early stage of the war there were nowhere near 10,000 people working at Bletchley Park. Still, there doubtless were a good many more working there than at PC Bruno, outside Paris.

- ^ Hugh Sebag-Montefiore, in reliance on Rejewski's unpublished 1967 Memoirs, gives a slightly different interpretation, apparently of the same episode: "The German Air Force was using an uncomplicated code for the weather forecasts it was relaying back to base. The substitutions involved in this code changed every day and the British codebreakers had spotted that they were always the same as the connections for the plugboard sockets on the Air Force Enigma system. So, as soon as the code was broken, the codebreakers knew the plugboard connections for the Air Force Enigma." Sebag-Montefiore (2004) pp. 87, 368.

- ^ According to Gwido Langer, the interruption in decryption was shorter, 13–19 May 1940. Kozaczuk 1984, p. 115, note 2.

- Knox's method, as well as others that Rejewski no longer remembered." (Kozaczuk 1984, p. 117)

- Christophe Léon Louis Juchault de Lamoricière, who had been involved in France's conquest of Algeria.

References

- ^ Bury 2004

- ^ Woytak 1988, pp. 497–500

- ^ a b c d Ścieżyński 1928

- ^ Kahn 1996

- ^ Nowik 2004, pp. 25–26

- ^ Ścieżyński 1928, pp. 16–17

- ^ Ścieżyński 1928, p. 19

- ^ Ścieżyński 1928, pp. 19–20

- ^ Ścieżyński 1928, p. 25

- ^ Ścieżyński 1928, pp. 25–26

- ^ a b c d Ścieżyński 1928, p. 26

- ^ a b c Kozaczuk 1984, p. 23, note 6

- ^ Kozaczuk 1984, p. 212

- ^ a b c d Rejewski 1984d, pp. 246–7

- ^ a b Rejewski & Woytak 1984b, pp. 230–231

- ^ Kozaczuk 1984, p. xiii

- ^ Sale, Tony. "Anoraks Corner: a quick revision of the Enigma machine, its physical and operational characteristics". Anoraks Corner. Retrieved 5 June 2011.

- ^ Kahn 1996, p. 974

- ^ Rejewski & Woytak 1984b, pp. 234–236

- ^ Rejewski & Woytak 1984b, p. 256

- ^ Kozaczuk 1984, pp. 258–259

- ^ Kozaczuk 1984, p. 25

- ^ Hodges 1992, p. 170

- ^ There were 26 × 26 × 26 = 17,576 possible rotor positions for each of the six rotor orders, giving a total of 105,456 possible indicators.

- ^ Calvocoressi 2001, p. 38 citing Rejewski 1984d, p. 263

- ^ a b Rejewski 1984c, p. 242

- Sale, Tony, ed. (1940). Der Schlüssel M Verfahren M Allgemein[The Enigma General Procedure] (PDF). Berlin: Supreme Command of the German Navy. Retrieved 26 November 2009 – via Bletchley Park.

- ^ Rejewski 1984d, p. 264

- ^ Rejewski 1984d, p. 265

- ^ Kozaczuk 1984, pp. 58, 64–66

- ^ Kozaczuk 1984, pp. 53, 212

- ^ Bomby is the plural of bomba.

- ^ Herivel 2008, p. 39, citing Rejewski 1984d, p. 269

- ^ Herivel 2008, pp. 39–40

- ^ Kozaczuk 1984, p. 66

- ^ a b Kozaczuk 1984, p. 43

- ^ Erskine 2006, p. 59

- ^ Herivel 2008, p. 55

- ^ Rejewski & Woytak 1984b, p. 236

- Pyry", Cryptologia, vol. 30, no. 4 (2006), pp. 294–305.

- ^ Rejewski 1984d, p. 257

- ^ Welchman 1982, p. 289

- ^ Winterbotham 1975, pp. 16–17

- ^ Winston Churchill, Their Finest Hour, pp. 598–600.

- ^ Kahn 1991

- ^ Christopher Kasparek, review of Michael Alfred Peszke, The Polish Underground Army, the Western Allies, and the Failure of Strategic Unity in World War II, 2005, in The Polish Review, vol. L, no. 2, 2005, p. 240.

- ^ Kozaczuk 1984, p. 60

- ^ Kozaczuk 1984, p. 70

- ^ Kozaczuk 1984, pp. 211–16

- ^ Kozaczuk 1984, pp. 69–94, 104–11

- ^ Kozaczuk 1984, pp. 70–87

- ^ Kozaczuk 1984, pp. 99, 102

- ^ Kozaczuk 1984, p. 79

- ^ Kozaczuk 1984, pp. 84, 94, note 8

- ^ Rejewski (1982) pp. 81–82

- ^ Also quoted in Kozaczuk 1984, p. 102

- ^ a b Kozaczuk 1984, p. 87

- ^ Kozaczuk 1984, pp. 87–88

- ^ Rejewski 1984c, p. 243

- ^ Rejewski 1984d, pp. 269–70

- ^ Bertrand (1973) pp. 88–89

- ^ Kozaczuk 1984, pp. 112–118

- ^ Kozaczuk 1984, p. 139

- ^ Kozaczuk 1984, pp. 139–40

- ^ Kozaczuk 1984, p. 116

- ^ Kozaczuk 1984, pp. 148–151

- ^ Kozaczuk 1984, p. 128

- ^ Kozaczuk 1984, pp. 150–51

- ^ Kozaczuk 1984, p. 154

- ^ Kozaczuk 1984, pp. 205–207

- ^ Kozaczuk 1984, pp. 148–155, 205–9

- ^ a b Kozaczuk 1984, p. 224

- ^ Kozaczuk 1984, pp. 224–26

- ^ Kozaczuk 1984, pp. 156, 220, note 4

- ^ Kozaczuk 1984, p. 156

- ^ Kozaczuk 1984, p. 220

- ^ Kozaczuk 1984, pp. 26, 212

- ^ Kozaczuk 1984, pp. 212–216

- ^ Kozaczuk 1984, p. xi

- ^ "Sekret Enigmy". IMDb. September 1979.

- ^ Peter, Laurence (20 July 2009). "How Poles cracked Nazi Enigma secret". BBC News.

Bibliography

- ISBN 978-0-444-51608-4

- Bloch, Gilbert (1987), "Enigma before Ultra: Polish Work and the French Contribution - Translated by C.A. Deavours", Cryptologia (published July 1987)

- ISBN 83-7208-117-4

- Bury, Jan (July 2004), "Polish Codebreaking during the Russo-Polish War of 1919–1920", Cryptologia, 28 (3): 193–203, S2CID 205486323

- ISBN 0-947712-41-0

- Churchill, Winston (1949), Their Finest Hour, Boston: Houghton Mifflin

- Comer, Tony (2021), Commentary: Poland's Decisive Role in Cracking Enigma and Transforming the UK's SIGINT Operations, Royal United Services Institute, archived from the original on 2021-02-08, retrieved 2021-01-30

- Ćwięk, Henryk (2001), Przeciw Abwehrze (Against the ISBN 978-83-11-09187-0

- Erskine, Ralph (December 2006), "The Poles Reveal their Secrets: Alastair Denniston's Account of the July 1939 Meeting at Pyry", Cryptologia, vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 294–305, S2CID 13410460

- Gaj, Kris; Orłowski, Arkadiusz, Facts and myths of Enigma: breaking stereotypes (PDF), George Mason University, Fairfax, VA 22030, U.S.A.; Institute of Physics, Polish Academy of Sciences Warszawa, Poland, archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-04-14, retrieved 1 February 2009

- Good, I.J., and Cipher A. Deavours, afterword to Marian Rejewski, "How Polish Mathematicians Deciphered the Enigma", Annals of the History of Computing, July 1981.

- ISBN 978-0-947712-46-4

- ISBN 978-0099116417

- ISBN 978-0-395-42739-2

- ISBN 068-483130-9

- Kozaczuk, Władysław (1999) [1967], Bitwa o Tajemnice: Służby wywiadowcze Polski i Niemiec 1918–1939 [The Struggle for Secrets: the Intelligence Services of Poland and Germany, 1918–1939] (in Polish), Warsaw: Książka i Wiedza

- ISBN 978-0-89093-547-7 A revised and augmented translation of W kręgu enigmy, Warsaw, Książka i Wiedza, 1979, supplemented with appendices by Marian Rejewski

- ISBN 978-0-7818-0941-2 Largely an abridgment of Kozaczuk 1984, minus Rejewski's appendices, which have been replaced with appendices of varying quality by other authors

- Misiuk, Andrzej (1998), Służby Specjalne II Rzeczypospolitej [Special Services in the Second [Polish] Republic] (in Polish), Warsaw: Bellona

- Nowik, Grzegorz (2004), Zanim złamano Enigmę: Polski radiowywiad podczas wojny z bolszewicką Rosją, 1918–1920 [Before Enigma Was Broken: Polish Radio Intelligence during the War with Bolshevik Russia, 1918–1920] (in Polish), Warsaw: Oficyna Wydawnicza Rytm, ISBN 83-7399-099-2

- Pepłoński, Andrzej (2002), Kontrwywiad II Rzeczypospolitej [Counterintelligence in the Second [Polish] Republic] (in Polish), Warsaw: Bellona

- Polmar, Norman; Allen, Thomas B. (2000), Księga Szpiegów [The Spy Book] (in Polish), Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Magnum

- ISSN 1730-6280

- Rejewski, Marian; Woytak, Richard (1984b), A Conversation with Marian Rejewski Appendix B to Kozaczuk 1984, pp. 229–40

- Rejewski, Marian (1984c), Summary of Our Methods for Reconstructing ENIGMA and Reconstructing Daily Keys, and of German Efforts to Frustrate Those Methods Appendix C to Kozaczuk 1984, pp. 241–245

- Rejewski, Marian (1984d), How the Polish Mathematicians Broke Enigma Appendix D to Kozaczuk 1984, pp. 246–271

- Rejewski, Marian (1984e), The Mathematical Solution of the Enigma Cipher Appendix E to Kozaczuk 1984, pp. 272–291

- Ścieżyński, Mieczysław (May 1928), Radjotelegrafja jako źródło wiadomości o nieprzyjacielu [Radiotelegraphy as a Source of Intelligence on the Enemy: Issued by permission of the General and Commander, Corps District No. X in Przemyśl, Register no. 2889/Train[ing]] (in Polish), Przemyśl: Printing and Binding Establishment of [Military] Corps District No. X HQ

- Welchman, Gordon (1982), The Hut Six Story: Breaking the Enigma Codes, New York: McGraw-Hill

- ISBN 978-0-7146-3299-5

- Winterbotham, F.W.(1975) [1974], The Ultra Secret, New York: Dell

- ISSN 0012-8449

External links

- Laurence Peter, How Poles cracked Nazi Enigma secret, BBC News, 20 July 2009

- "Polish Enigma Double" Archived 2007-03-12 at the Wayback Machine

- "The Enigma Code Breach," by Jan Bury

- Enigma

- Enigma and Intelligence Archived 2007-07-11 at the Wayback Machine

- "Codebreaking and Secret Weapons in World War II," by Bill Momsen

- A Brief History of Computing Technology, 1930 to 1939

- "The Poles Crack Enigma" (from Greg Goebel's Codes, Ciphers, & Codebreaking)

- NSA/CSS National Cryptologic Museum Unveils New Polish Enigma Exhibit

- IEEE History Center: "The Invention of Enigma and How the Polish Broke It Before the Start of WWII"

- The Breaking of Enigma by the Polish Mathematicians

- Sir Dermot Turing said that his uncle's achievements in cracking German communications encrypted on the Enigma machines were based on work by a group of Polish mathematicians: Turing cult has obscured role of Polish codebreakers