Polish culture during World War II

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Poland |

|---|

|

| Traditions |

|

Mythology |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Religion |

Polish culture during

The occupiers looted and destroyed much of Poland's cultural and historical heritage while persecuting and murdering members of the Polish cultural elite. Most Polish schools were closed, and those that remained open saw their curricula altered significantly.

Nevertheless, underground organizations and individuals—in particular the Polish Underground State—saved much of Poland's most valuable cultural treasures, and worked to salvage as many cultural institutions and artifacts as possible. The Catholic Church and wealthy individuals contributed to the survival of some artists and their works. Despite severe retribution by the Nazis and Soviets, Polish underground cultural activities, including publications, concerts, live theater, education, and academic research, continued throughout the war.

Background

In 1795 Poland ceased to exist as a sovereign nation and throughout the 19th century remained partitioned by degrees between Prussian, Austrian and Russian empires. Not until the end of World War I was independence restored and the nation reunited, although the drawing of boundary lines was, of necessity, a contentious issue. Independent Poland lasted for only 21 years before it was again attacked and divided among foreign powers.

On 1 September 1939,

Destruction of Polish culture

German occupation

Policy

Germany's policy toward the Polish nation and its culture evolved during the course of the war. Many German officials and military officers were initially not given any clear guidelines on the treatment of Polish cultural institutions, but this quickly changed.

Much of the German policy on Polish culture was formulated during a meeting between the governor of the General Government,

In March 1940, all cultural activities came under the control of the General Government's Department of People's Education and Propaganda (Abteilung für Volksaufklärung und Propaganda), whose name was changed a year later to the "Chief Propaganda Department" (Hauptabteilung Propaganda).

In 1941, German policy evolved further, calling for the complete destruction of the Polish people, whom the Nazis regarded as "subhumans" (Untermenschen). Within ten to twenty years, the Polish territories under German occupation were to be entirely cleared of ethnic Poles and settled by German colonists.[9][14] The policy was relaxed somewhat in the final years of occupation (1943–44), in view of German military defeats and the approaching

Given that the

Plunder

In 1939, as the occupation regime was being established, the Nazis confiscated Polish state property and much private property.

Destruction

Many places of learning and culture—universities, schools, libraries, museums, theaters and cinemas—were either closed or designated as "Nur für Deutsche" (For Germans Only). Twenty-five museums and a host of other institutions were destroyed during the war.[24] According to one estimate, by war's end 43% of the infrastructure of Poland's educational and research institutions and 14% of its museums had been destroyed.[27] According to another, only 105 of pre-war Poland's 175 museums survived the war, and just 33 of these institutions were able to reopen.[28] Of pre-war Poland's 603 scientific institutions, about half were totally destroyed, and only a few survived the war relatively intact.[29]

Many university professors, as well as teachers, lawyers, artists, writers, priests and other members of the Polish

As part of their program to suppress Polish culture, the German Nazis attempted to destroy

To forestall the rise of a new generation of educated Poles, German officials decreed that the schooling of Polish children would be limited to a few years of elementary education.

The state of Polish primary schools was somewhat better in the General Government,[38] though by the end of 1940, only 30% of prewar schools were operational, and only 28% of prewar Polish children attended them.[41] A German police memorandum of August 1943 described the situation as follows:

Pupils sit crammed together without necessary materials, and often without skilled teaching staff. Moreover, the Polish schools are closed during at least five months out of the ten months of the school year due to lack of coal or other fuel. Of twenty-thirty spacious school buildings which Kraków had before 1939, today the worst two buildings are used ... Every day, pupils have to study in several shifts. Under such circumstances, the school day, which normally lasts five hours, is reduced to one hour.[38]

In the General Government, the remaining schools were subjugated to the German educational system, and the number and competence of their Polish staff was steadily scaled down.[39] All universities and most secondary schools were closed, if not immediately after the invasion, then by mid-1940.[9][39][42] By late 1940, no official Polish educational institutions more advanced than a vocational school remained in operation, and they offered nothing beyond the elementary trade and technical training required for the Nazi economy.[38][41] Primary schooling was to last for seven years, but the classes in the final two years of the program were to be limited to meeting one day per week.[41] There was no money for heating the schools in winter.[43] Classes and schools were to be merged, Polish teachers dismissed, and the resulting savings used to sponsor the creation of schools for children of the German minority or to create barracks for German troops.[41][43] No new Polish teachers were to be trained.[41] The educational curriculum was censored; subjects such as literature, history and geography were removed.[38][39][44] Old textbooks were confiscated and school libraries were closed.[38][44] The new educational aims for Poles included convincing them that their national fate was hopeless and teaching them to be submissive and respectful to Germans. This was accomplished through deliberate tactics such as police raids on schools, police inspections of student belongings, mass arrests of students and teachers, and the use of students as forced laborers, often by transporting them to Germany as seasonal workers.[38]

The Germans were especially active in the destruction of Jewish culture in Poland; nearly all of the wooden synagogues there were destroyed.[45] Moreover, the sale of Jewish literature was banned throughout Poland.[46]

Polish literature faced a similar fate in territories annexed by Germany, where the sale of Polish books was forbidden.[46] The public destruction of Polish books was not limited to those seized from libraries, but also included those books that were confiscated from private homes.[47] The last Polish book titles not already proscribed were withdrawn in 1943; even Polish prayer books were confiscated.[48] Soon after the occupation began, most libraries were closed; in Kraków, about 80% of the libraries were closed immediately, while the remainder saw their collections decimated by censors.[10] The occupying powers destroyed Polish book collections, including the Sejm and Senate Library, the Przedziecki Estate Library, the Zamoyski Estate Library, the Central Military Library, and the Rapperswil Collection.[22][49] In 1941, the last remaining Polish public library in the German-occupied territories was closed in Warsaw.[48] During the war, Warsaw libraries lost about a million volumes, or 30% of their collections.[50] More than 80% of these losses were the direct result of purges rather than wartime conflict.[51] Overall, it is estimated that about 10 million volumes from state-owned libraries and institutions perished during the war.[27]

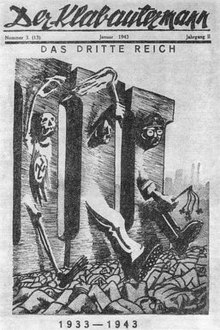

Censorship and propaganda

The Germans prohibited publication of any regular Polish-language book, literary study or scholarly paper.[22][48] In 1940, several German-controlled printing houses began operating in occupied Poland, publishing items such as Polish-German dictionaries and antisemitic and anticommunist novels.[54]

Poles were forbidden, under penalty of death, to own

Music was the least restricted of cultural activities, probably because Hans Frank regarded himself as a fan of serious music. In time, he ordered the creation of the Orchestra and Symphony of the General Government in its capital, Kraków.[10] Numerous musical performances were permitted in cafes and churches,[10] and the Polish underground chose to boycott only the propagandist operas.[10] Visual artists, including painters and sculptors, were compelled to register with the German government; but their work was generally tolerated by the underground unless it conveyed propagandist themes.[10] Shuttered museums were replaced by occasional art exhibitions that frequently conveyed propagandist themes.[10]

The development of

Soviet occupation

After the

The Soviet authorities regarded service to the prewar Polish state as a "crime against revolution"[61] and "counter-revolutionary activity"[62] and arrested many members of the Polish intelligentsia, politicians, civil servants and academics, as well as ordinary persons suspected of posing a threat to Soviet rule. More than a million Polish citizens were deported to Siberia,[63][64] many to Gulag concentration camps, for years or decades. Others died, including over 20,000 military officers who perished in the Katyn massacres.[65]

The Soviets quickly

The Soviet authorities sought to remove all traces of the Polish history of the area now under their control.

All publications and media were subjected to censorship.[67] The Soviets sought to recruit Polish left-wing intellectuals who were willing to cooperate.[67][72][73] Soon after the Soviet invasion, the Writers' Association of Soviet Ukraine created a local chapter in Lwów; there was a Polish-language theater and radio station.[72] Polish cultural activities in Minsk and Vilnius were less organized.[72] These activities were strictly controlled by the Soviet authorities, which saw to it that these activities portrayed the new Soviet regime in a positive light and vilified the former Polish government.[72]

The Soviet propaganda-motivated support for Polish-language cultural activities, however, clashed with the official policy of

Many Polish writers collaborated with the Soviets, writing pro-Soviet propaganda.[72][73] They included Jerzy Borejsza, Tadeusz Boy-Żeleński, Kazimierz Brandys, Janina Broniewska, Jan Brzoza, Teodor Bujnicki, Leon Chwistek, Zuzanna Ginczanka, Halina Górska, Mieczysław Jastrun, Stefan Jędrychowski, Stanisław Jerzy Lec, Tadeusz Łopalewski, Juliusz Kleiner, Jan Kott, Jalu Kurek, Karol Kuryluk, Leopold Lewin, Anatol Mikułko, Jerzy Pański, Leon Pasternak, Julian Przyboś, Jerzy Putrament, Jerzy Rawicz, Adolf Rudnicki, Włodzimierz Słobodnik, Włodzimierz Sokorski, Elżbieta Szemplińska, Anatol Stern, Julian Stryjkowski, Lucjan Szenwald, Leopold Tyrmand, Wanda Wasilewska, Stanisław Wasilewski, Adam Ważyk, Aleksander Weintraub and Bruno Winawer.[72][73]

Other Polish writers, however, rejected the Soviet persuasions and instead published underground: Jadwiga Czechowiczówna, Jerzy Hordyński, Jadwiga Gamska-Łempicka, Herminia Naglerowa, Beata Obertyńska, Ostap Ortwin, Tadeusz Peiper, Teodor Parnicki, Juliusz Petry.[72][73] Some writers, such as Władysław Broniewski, after collaborating with the Soviets for a few months, joined the anti-Soviet opposition.[72][73][76] Similarly, Aleksander Wat, initially sympathetic to communism, was arrested by the Soviet NKVD secret police and exiled to Kazakhstan.[73]

Underground culture

Patrons

Other important patrons of Polish culture included the

Education

In response to the German closure and censorship of Polish schools, resistance among teachers led almost immediately to the creation of

In

The German attitude to underground education varied depending on whether it took place in the General Government or the annexed territories. The Germans had almost certainly realized the full scale of the Polish underground education system by about 1943 but lacked the manpower to put an end to it, probably prioritizing resources to dealing with the armed resistance.

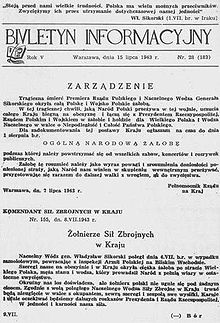

There were over 1,000 underground newspapers;

The two largest underground publishers were the

Under German occupation, the professions of Polish journalists and writers were virtually eliminated, as they had little opportunity to publish their work. The Underground State's Department of Culture sponsored various initiatives and individuals, enabling them to continue their work and aiding in their publication.

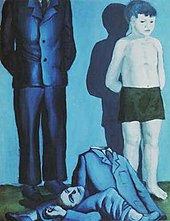

Visual arts and music

With the censorship of Polish theater (and the virtual end of the Polish radio and film industry),

Polish music, including orchestras, also went underground.

Visual arts were practiced underground as well. Cafes, restaurants and private homes were turned into galleries or museums; some were closed, with their owners, staff and patrons harassed, arrested or even executed.

Warsaw Uprising

During the Warsaw Uprising (August–October 1944), people in Polish-controlled territory endeavored to recreate the former day-to-day life of their free country. Cultural life was vibrant among both soldiers and the civilian population, with theaters, cinemas, post offices, newspapers and similar activities available.[118] The 10th Underground Tournament of Poetry was held during the Uprising, with prizes being weaponry (most of the Polish poets of the younger generation were also members of the resistance).[107] Headed by Antoni Bohdziewicz, the Home Army's Bureau of Information and Propaganda even created three newsreels and over 30,000 metres (98,425 ft) of film documenting the struggle.[119] Eugeniusz Lokajski took some 1,000 photographs before he died;[120] Sylwester Braun some 3,000, of which 1,500 survive;[121] Jerzy Tomaszewski some 1,000, of which 600 survived.[122]

Culture in exile

Polish artists also worked abroad, outside of

Influence on postwar culture

The wartime attempts to destroy Polish culture may have strengthened it instead.

The experience of World War II placed its stamp on a

Over the years, nearly three-quarters of the Polish people have emphasized the importance of World War II to the Polish national identity. Educational and training programs place special emphasis on the World War II period and on the occupation. Events and individuals connected with the war are ubiquitous on TV, on radio and in the print media. The theme remains an important element in literature and learning, in film, theater and the fine arts. Not to mention that politicians constantly make use of it. Probably no other country marks anniversaries related to the events of World War II so often or so solemnly.[134]

See also

- Football in occupied Poland (1939–1945)

- Home front during World War II

- Nazi crimes against ethnic Poles

- The Holocaust in Poland

Notes

- ^ Olsak-Glass, Judith (January 1999). "Review of Piotrowski's Poland's Holocaust". Sarmatian Review. Retrieved January 24, 2008.

The prisons, ghettos, internment, transit, labor and extermination camps, roundups, mass deportations, public executions, mobile killing units, death marches, deprivation, hunger, disease, and exposure all testify to the 'inhuman policies of both Hitler and Stalin' and 'were clearly aimed at the total extermination of Polish citizens, both Jews and Christians. Both regimes endorsed a systematic program of genocide.'

- ^ OCLC 44068966.

- ^ Schabas 2000.

- ^ a b Ferguson 2006, p. 423

- ^ Raack 1995, p. 58

- ^ Piotrowski 1997, p. 295

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Madajczyk 1970, pp. 127–129

- ^ Madajczyk, Czesław (1980). "Die Besatzungssysteme der Achsenmächte: Versuch einer komparatistischen Analyse". Studia Historiae Oeconomicae (in German). 14.

- ^ a b c d e Redzik, Adam (September 30 – October 6, 2004). Polish Universities During the Second World War (PDF). Encuentros de Historia Comparada Hispano-Polaca / Spotkania poświęcone historii porównawczej hiszpańsko-polskiej (Fourth Meeting of Comparative Hispano-Polish History). Retrieved May 27, 2009.

- ^ ISSN 1427-7476.

- ^ a b c d Madajczyk 1970, p. 130

- ^ Madajczyk 1970, p. 137

- ^ Madajczyk 1970, pp. 130–132.

- )

- ^ Madajczyk 1970, pp. 133–134

- ^ a b c d e f g Madajczyk 1970, pp. 132–133

- ^ Davies 2005, p.299

- ^ a b c Madajczyk 1970, pp. 169–170

- ^ a b Madajczyk 1970, pp. 171–173

- ^ Madajczyk 1970, pp. 162–163

- ^ Kiriczuk, Jurij (April 23, 2003). "Jak za Jaremy i Krzywonosa". Gazeta Wyborcza (in Polish). Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f Knuth & English 2003, pp. 86–89

- ^ a b c d e Madajczyk 1970, p. 122.

- ^ a b c "Rewindykacja dóbr kultury". Polish Ministry of Foreign Affairs (in Polish). Archived from the original on August 21, 2007. Retrieved June 15, 2008.

- ^ Tygodnik Przegląd (in Polish). No. 40. Archived from the original on November 3, 2005.)

{{cite magazine}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link - ^ Kisling 2001, pp. 122–123.

- ^ a b Salmonowicz 1994, p. 229

- ^ a b c Madajczyk 1970, p. 123

- ^ Madajczyk 1970, p. 127

- ^ Grabski, Józef (2003). "Zaginiony "Portret młodzieńca" Rafaela ze zbiorów XX. Czartoryskich w Krakowie. Ze studiów nad typologią portretu renesansowego". In Dudzik, Sebastian; Żuchowski, Tadeusz J. (eds.). Rafael i jego spadkobiercy. Portret klasyczny w sztuce nowożytnej Europy (in Polish). Vol. 4. pp. 221–261.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Burek, Edward, ed. (2000). "Sonderaktion Krakau". Encyklopedia Krakowa (in Polish). Kraków: PWM.

- OCLC 29278609.

- ^ Sieradzki, Sławomir (September 21, 2003). "Niemiecki koń trojański". Wprost (in Polish). No. 38. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ a b c Phayer 2001, p. 22

- ^ a b Conway 1997, pp. 325–326

- ^ Conway 1997, pp. 299–300

- ^ a b "Poles: Victims of the Nazi Era". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Archived from the original on 2013-03-03. Retrieved 2008-01-24.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7507-0054-2.

- ^ a b c d Bukowska, Ewa (2003). "Secret Teaching in Poland in the Years 1939 to 1945". London Branch of the Polish Home Army Ex-Servicemen's Association. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ a b Madajczyk 1970, pp. 142–148

- ^ a b c d e Madajczyk 1970, p. 149

- ^ Salmonowicz 1994, pp. 201–202

- ^ a b Madajczyk 1970, p. 151

- ^ a b Madajczyk 1970, p. 150

- ^ Hubka 2003, p. 57.

- ^ a b c d Salmonowicz 1994, pp. 269–272

- ^ Madajczyk 1970, p. 124

- ^ a b c d e f g Anonymous (1945). The Nazi Kultur in Poland. London: Polish Ministry of Information. Retrieved January 23, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f Ostasz, Grzegorz (2004). "Polish Underground State's Patronage of the Arts and Literature (1939–1945)". London Branch of the Polish Home Army Ex-Servicemen Association. Retrieved March 20, 2008.

- ^ a b c Madajczyk 1970, p. 125

- ^ Madajczyk 1970, p. 126

- ^ Salmonowicz 1994, p. 199

- ^ a b Salmonowicz 1994, p. 204

- ^ Drozdowski & Zahorski 2004, p. 449.

- ^ a b Salmonowicz 1994, p. 179

- ^ Madajczyk 1970, p. 167

- ^ Szarota 1988, p. 323

- ^ Madajczyk 1970, pp. 135

- ^ a b c Madajczyk 1970, pp. 138

- ^ Polish Ministry of Information, Concise Statistical Year-Book of Poland, London, June 1941, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Herling-Grudziński 1996, p. 284

- ^ Anders 1995, p. 540

- ^ Lerski, Lerski & Lerski 1996, p.538

- ^ Raack 1995, p. 65

- ^ a b c d e Trela-Mazur 1997, pp. 89–125

- ^ Piotrowski 1997, p. 11

- ^ a b c d Raack 1995, p. 63

- ^ Davies 1996, pp. 1001–1003

- ^ Gehler & Kaiser 2004, p. 118

- ^ Ferguson 2006, p. 419

- ^ Ferguson 2006, p. 418

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Węglicka, Katarzyna (12 May 2008). "Literatura okupacyjna na Kresach" [Occupation literature in Kresy]. Kresy - Wiadomości, Wydarzenia, Aktualności, Newsy (in Polish). Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kołodziejski, Konrad (September 21, 2003). "Elita niewolników Stalina". Wprost (in Polish). No. 38. Retrieved May 10, 2009.

- ^ a b Raack 1995, pp. 63–64

- ^ Lukowski & Zawadzki 2006, p. 228.

- ^ Piotrowski 1997, pp. 77–80.

- ^ a b Courtney, Krystyna Kujawinska (2000), "Shakespeare in Poland", Shakespeare Around the Globe, Internet Shakespeare Editions, University of Victoria, archived from the original on 2008-01-07, retrieved 2008-01-24

- ^ a b Salmonowicz 1994, p. 235

- ^ Salmonowicz 1994, p. 233

- ^ "Tajna Organizacja Nauczycielska". WIEM Encyklopedia (in Polish). Retrieved June 15, 2008.

- ^ a b Madajczyk 1970, pp. 155–156

- ^ Salmonowicz 1994, p. 208

- ^ Czekajowski, Ryszard (2005). "Tajna edukacja cywilna w latach wojenno-okupacyjnych Polski 1939–1945" (in Polish). Retrieved April 7, 2009.

- ^ Korboński 1975, p. 56

- ^ a b Salmonowicz 1994, p. 213

- ^ a b Parker, Christine S (2003). History of Education Reform in Post-Communism Poland, 1989–1999: Historical and Contemporary Effects on Educational Transition (Doctor of Philosophy thesis). The Ohio State University. Archived from the original on September 28, 2003.

- ^ Madajczyk 1970, pp. 160–161

- ^ Salmonowicz 1994, pp. 215, 221

- ^ Salmonowicz 1994, p. 222

- ^ Salmonowicz 1994, p. 223

- ^ Salmonowicz 1994, p. 226

- ^ Salmonowicz 1994, p. 225

- ^ Salmonowicz 1994, p. 227

- ^ Salmonowicz 1994, p. 228

- ^ a b c Madajczyk 1970, pp. 158–159

- ^ a b c Madajczyk 1970, pp. 150–151

- ^ Madajczyk 1970, pp. 158–160

- ^ Salmonowicz 1994, p. 189

- ^ a b Salmonowicz 1994, p. 190

- ^ a b Hempel 2003, p. 54

- ^ a b Salmonowicz 1994, p. 185

- ^ Salmonowicz 1994, p. 187

- ^ "Tajne Wojskowe Zakłady Wydawnicze". WIEM Encyklopedia (in Polish). Retrieved June 15, 2008.

- ^ a b c Salmonowicz 1994, p. 196

- ^ Salmonowicz 1994, p. 184

- ^ a b c Salmonowicz 1994, pp. 236–237

- ^ a b Salmonowicz 1994, p. 244

- ^ a b c Salmonowicz 1994, pp. 272–75

- ^ a b c d Salmonowicz 1994, pp. 245–52

- ^ Kremer 2003, [https://books.google.com/books?id=BAQ2VtfH3awC&pg=PA1183 p. 1183.

- ^ Sterling & Roth 2005, p. 283.

- ^ a b Madajczyk 1970, p. 140

- ^ a b c d Salmonowicz 1994, pp. 252–56

- ^ Gilbert 2005, p. vii.

- ^ a b c d e f Salmonowicz 1994, pp. 256–65

- ^ Stoliński, Krzysztof (2004). Supply of money to the Secret Army (AK) and the Civil Authorities in occupied Poland (1939–1945) (PDF). Symposium on the occasion of the 60th Anniversary of the Warsaw Rising 1944. Polish Underground Movement (1939–1945) Study Trust (PUMST). London: Polish Institute and Sikorski Museum. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 28, 2011.

- ^ Moczydłowski, Jan (1989). "Produkcja banknotów przez Związek Walki Zbrojnej i Armię Krajową". Biuletyn Numizmatyczny (in Polish): 10–12.

- ^ Nawrocka-Dońska 1961

- Warsaw Uprising Museum. Retrieved 2008-01-25.

- ^ "Warsaw Kolekcja zdjęć Eugeniusza Lokajskiego" (in Polish). Muzeum Powstania Warszawskiego. December 8, 2003.

- OCLC 11782581.

- ^ Struk, Janina (July 28, 2005). "My duty was to take pictures". The Guardian.

- ^ Salmonowicz 1994, p. 240

- ^ Cholewa-Selo, Anna (Mar 3, 2005). "Muza i Jutrzenka. Wywiad z Ireną Andersową, żoną Generała Władysława Andersa". Cooltura (in Polish). Retrieved April 7, 2009.

- ^ Murdoch 1990, p. 195. Google Print, p. 195.

- ^ "Polska. Teatr. Druga wojna światowa". Encyklopedia PWN (in Polish). Archived from the original on June 7, 2011. Retrieved May 5, 2009.

- ^ Supruniuk, Mirosław Adam. "Malarstwo polskie w Wielkiej Brytanii – prace i dokumenty" (in Polish). Uniwersytet Mikołaja Kopernika. Archived from the original on May 6, 2009. Retrieved May 5, 2009.

- ^ Davies 2005, p.174

- ^ Salmonowicz 1994, pp. 211, 221

- ^ Haltof 2002, p. 223.

- ^ Cornis-Pope & Neubauer 2004, p. 146.

- ^ Klimaszewski 1984, p. 343.

- ^ Haltof 2002, p. 76.

- ^ a b Ruchniewicz, Krzysztof (September 5, 2007). "The memory of World War II in Poland". Eurozine. Archived from the original on November 10, 2007. Retrieved March 26, 2008.

References

- ISBN 83-7038-168-5

- ISBN 1-57383-080-1

- Cornis-Pope, Marcel; Neubauer, John (2004), History of the Literary Cultures of East-Central Europe, John Benjamins Publishing Company, ISBN 90-272-3452-3

- ISBN 0-19-820171-0

- Davies, Norman (2005), ISBN 0-231-12819-3

- Drozdowski, Marian Marek; OCLC 69583611.

- Ferguson, Niall (2006), The War of the World, New York: Penguin Press

- Gehler, Michael; ISBN 0-7146-8567-4

- Gilbert, Shirli (2005), Music in the Holocaust: Confronting Life in the Nazi Ghettos and Camps, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-927797-4

- ISBN 1-57181-276-8

- Hempel, Andrew (2003), Poland in World War II: An Illustrated Military History, Hippocrene Books, ISBN 0-7818-1004-3

- ISBN 0-14-025184-7

- ISBN 1-58465-216-0

- Kisling, Vernon N. (2001), Zoo and Aquarium History: Ancient Animal Collections to Zoological Gardens, CRC Press, ISBN 0-8493-2100-X

- Klimaszewski, Bolesław (1984), An Outline History of Polish Culture, Interpress, ISBN 83-223-2036-1

- Knuth, Rebecca; English, John (2003). Libricide: The Regime-sponsored Destruction of Books and Libraries in the Twentieth Century. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 86–89. ISBN 978-0-275-98088-7.

- Korboński, Stefan (1975), Polskie państwo podziemne: przewodnik po Podziemiu z lat 1939-1945 (in Polish), Bydgoszcz: Wydawnictwo Nasza Przyszłość

- Kremer, S. Lillian (2003), Holocaust literature: an encyclopedia of writers and their work, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 0-415-92984-9

- ISBN 978-0-313-26007-0.

- ISBN 0-521-61857-6

- Madajczyk, Czesław (1970), Polityka III Rzeszy w okupowanej Polsce, Tom II (Politics of the Third Reich in Occupied Poland, Part Two) (in Polish), Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe

- Murdoch, Brian (1990), Fighting Songs and Warring Words: Popular Lyrics of Two World Wars, Routledge

- Nawrocka-Dońska, Barbara (1961), Powszedni dzień dramatu (An average day in the drama) (in Polish) (1 ed.), Warsaw: Czytelnik

- ISBN 0-253-21471-8

- ISBN 0-7864-0371-3

- Raack, Richard (1995), Stalin's Drive to the West, 1938–1945, Stanford University Press, ISBN 0-8047-2415-6

- ISBN 83-02-05500-X

- ISBN 0-521-78790-4

- Sterling, Eric; ISBN 0-8156-0803-9

- ISBN 83-07-01224-4

- ISBN 8371331002

Further reading

- Krauski, Josef (1992), "Education as Resistance: The Polish Experience of Schooling During the War", in Roy Lowe (ed.), Education and the Second World War: Studies in Schooling and Social Change, Falmer Press, ISBN 0-7507-0054-8

- Mężyńskia, Andrzej; Paszkiewicz, Urszula; Bieńkowska, Barbara (1994), Straty bibliotek w czasie II wojny światowej w granicach Polski z 1945 roku. Wstępny raport o stanie wiedzy (Losses of Libraries During World War II within the Polish Borders of 1945. An Introductory Report on the State of Knowledge) (in Polish), Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Reklama, ISBN 83-902167-0-1

- Ordęga, Adam; Terlecki, Tymon (1945), Straty kultury polskiej, 1939–1944 (Losses of Polish Culture, 1939–1944) (in Polish), Glasgow: Książnica Polska

- Pruszynski, Jan P.h (1997), "Poland: The War Losses, Cultural Heritage, and Cultural Legitimacy", in Simpson, Elizabeth (ed.), The Spoils of War: World War II and Its Aftermath: The Loss, Reappearance, and Recovery of Cultural Property, New York: Harry N. Abrams, ISBN 0-8109-4469-3

- Symonowicz, Antoni (1960), "Nazi Campaign against Polish Culture", in Nurowski, Roman (ed.), 1939–1945 War Losses in Poland, Poznan: Wydaw- nictwo Zachodnie, OCLC 47236461

External links

- Lukaszewski, Witold J. (April 1998), "Polish Losses in World War I", The Sarmatian Review

- The German New Order in Poland: Part 1, Part 2

- Polish Department of National Heritage: Wartime losses – list of publications (mirror[permanent dead link])

- Polish War losses during World War II – gallery on Wikimedia Commons

- Polish World War II posters of Occupied Poland[permanent dead link] – gallery on Wikimedia Commons

- World War II in Poland, its Impact on Everyday Life; Personal Perspective

- The Nazi Kultur in Poland by several authors of necessity temporarily anonymous written in Warsaw during the German Occupation