Polish prisoners-of-war in the Soviet Union after 1939

As a result of the

Soviet invasion of Poland

On September 17, 1939, the Red Army invaded the territory of Poland from the east. The invasion took place while Poland was already sustaining serious defeats in the wake of the

During the

The Soviets often failed to honour the terms of surrender. In some cases, they promised Polish soldiers freedom after capitulation and then arrested them when they laid down their arms., the exact number of those killed has not been established.

First period (1939–1941)

Some Polish prisoners were freed or escaped, but 125,000 found themselves incarcerated in prison camps run by the NKVD.[13] Of these, the Soviet authorities released 42,400 soldiers (mostly soldiers of Ukrainian and Belarusian ethnicity serving in the Polish army who lived in the former Polish territories now annexed by the Soviet Union) in October.[14][15][16] The 43,000 soldiers born in West Poland, then under German control, were transferred to the Germans; in turn the Soviets received 13,575 Polish prisoners from the Germans.[16][15]

Poland and the Soviet Union never officially declared war on each other in 1939; the Soviets effectively broke off

As early as September 19, 1939, the People's Commissar for Internal Affairs and First Rank Commissar of State Security,

Kozelsk and Starobielsk held mainly military officers, while Ostashkov was used mainly for

- Kozelsk, 5,000

- Ostashkov, 6,570

- Starobelsk (Katyn forest), 4,000

They totalled 15,570 men.[21]

According to a report from 19 November 1939, the NKVD had about 40,000 Polish POWs: about 8,000-8,500 officers and warrant officers, 6,000–6,500 police officers and 25,000 soldiers and NCOs who were still being held as POWs.[22][failed verification][16][23][24] In December, a wave of arrests took into custody some Polish officers who were not yet imprisoned; Ivan Serov reported to Lavrentiy Beria on 3 December that "in all, 1,057 former officers of the Polish Army had been arrested".[15] The 25,000 soldiers and non-commissioned officers were assigned to forced labor (road construction, heavy metallurgy).[15]

Once at the camps, from October 1939 to February 1940, the Poles were subjected to lengthy interrogations and constant political agitation by NKVD officers such as Vasily Zarubin. The Soviets encouraged the Poles to believe they would be released,[25] but the interviews were in effect a selection process to determine who would live and who would die.[1] According to NKVD reports, the prisoners could not be induced to adopt a pro-Soviet attitude.[21] They were declared "hardened and uncompromising enemies of Soviet authority".[1]

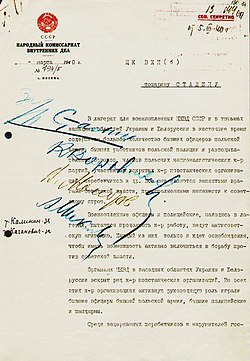

On March 5, 1940, a note to Joseph Stalin from Beria saw the members of the Soviet Politburo — Stalin, Vyacheslav Molotov, Lazar Kaganovich, Mikhail Kalinin, Kliment Voroshilov, Anastas Mikoyan and Beria — signed an order for the execution of "nationalists and counter-revolutionaries" kept at camps and prisons in western Ukraine and Belarus. This execution became known as the Katyn massacre, where 22,000 perished[1][2]

Second period (1941–1944)

Diplomatic relations were, however, re-established in 1941 after the

Third period (after 1944)

The third group of Polish prisoners were members of Polish resistance organizations (

Polish generals killed by the Soviets in 1939–1945

- Polish Army of the Second Polish Republic. In September 1939, when the German Army and the Soviet Army invaded Poland, he moved to Grodno, where he was captured by the NKVDa month later. He has been missing since then, presumably killed by the NKVD.

- Starobielsk and executed in Kharkiv.

- Katyń massacre. He was one of only two generals identified during exhumation in 1943.

- Kiev in June 1940 and accused of list of 'crimes'. The last trace of the general is receipt put by the commander of convoy in December 1940. The general was likely shot by a firing squad in Moscowin 1941.

- Starobielsk, KozielskSoviet camp, he was eventually murdered in the Katyń massacre.

- Kievin 1940. His fate is unknown, but he is suspected to have died of exhaustion in the Kiev prison.

- Stanisław Haller de Hallenburg - Lieutenant General, arrested in 1939 and imprisoned in Starobielsk. In 1941, when Władysław Sikorskihad issued the order to form Polish Army in the Soviet Union after the outbreak of war between Germany and the Soviet Union, Stanisław Haller was to be appointed the Commander in Chief of that army. Oblivious to Sikorski, Haller had been dead since 1940, when he fell victim to the Katyń massacre.

- Kazimierz Horoszkiewicz - nominal Lieutenant General in the Polish Army of the Second Polish Republic, in September 1939, eluding the Germans he arrived to Lviv, at that time already under the Soviet occupation. Having been sent to Siberia, Horoszkiewicz had died in Tobolsk on his way back to the west, to newly formed Polish units in the Soviet Union in 1942.

- Albin Jasiński - Brigadier General, organized Polish Self-Defence units in Drohiczyn against the Soviet oppression in 1939. He was detained by the NKVD, and died in 1940 during tortures inflicted by the NKVD interrogators.

- Aleksander Walenty Jasiński - Brigadier General, he disappeared after the Soviets had entered Lviv. His fate has been unknown since.

- Marian Jasiński - nominal Brigadier General, he has been lost from the Soviet invasion, likely killed by the Soviets.

- Adolf Karol Jastrzębski - Brigadier General, imprisoned by the Soviets, sent to gulag in Vologda, died of hard labour, exhaustion and hunger.

- Władysław Jędrzejewski - Lieutenant General, he was organizing the Self-Defence units in Lviv, when the Soviet army entered the city. He was executed in 1940 by the NKVD.

- Władysław Jung - Lieutenant General, the Soviet aggression caught him in Lviv. He made failed attempt to cross the German-Soviet demarcation line in 1939. Kept in prison on severe cold, he died of gangrene.

- Juliusz Klemens Kolmer - Brigadier General, arrested by NKVD in Lviv, 1940. He was presumably killed by the Soviets.

- Aleksander Kowalewski (general) - Brigadier General, he prepared operation group in Podolia during September Campaign in 1939. When the news of the Soviet invasion had reached him, General Kowalewski set off on the southeastern direction, where he clashed with approaching Soviet army. In the meantime, General of the Armies announced the directive not to engage Soviets unless provoked. General Kowalewski followed the order and capitulated to Soviets. Imprisoned and relocated to Starobielsk, murdered in Kharkiv in 1940.

- Szymon Kurz - Brigadier General, arrested in November 1939 by the NKVD. Executed in the spring of 1940.

- Kazimierz Orlik-Łukoski - Major General, was captured during the German–Soviet invasion and later turned over to the NKVD. He was imprisoned in Starobielsk, and later killed in the Katyń massacre.

See also

- Camps for Polish prisoners and internees in Soviet Union and Lithuania (1919-1921)

- Treatment of Polish citizens by occupiers

- Sybiraks

- Camps for Russian prisoners and internees in Poland (1919–1924)

References

- ^ a b c d Fischer, Benjamin B., "The Katyn Controversy: Stalin's Killing Field", Studies in Intelligence, Winter 1999-2000.

- ^ Sanford, Google Books, p. 20–24.

- ^ Encyklopedia PWN 'KAMPANIA WRZEŚNIOWA 1939' Archived May 9, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, last retrieved on 10 December 2005, Polish language

- ^ Stanley S. Seidner, Marshal Edward Śmigły-Rydz Rydz and the Defense of Poland, New York, 1978.

- ^ ISSN 1734-6584. (Official publication of the Polish Army). Retrieved 28 November 2006.

- ^ (in Polish) obozy jenieckie żołnierzy polskich Archived 2013-11-04 at the Wayback Machine (Prison camps for Polish soldiers) Encyklopedia PWN. Retrieved 28 November 2006.

- ^ (in Russian) Молотов на V сессии Верховного Совета 31 октября цифра «примерно 250 тыс.» (Please provide translation of the reference title and publication data and means)

- ^ (in Russian) Отчёт Украинского и Белорусского фронтов Красной Армии Мельтюхов, с. 367. [1][permanent dead link] (Please provide translation of the reference title and publication data and means)

- ^ (in Polish) Olszyna-Wilczyński Józef Konstanty Archived 2008-03-06 at the Wayback Machine, entry at Encyklopedia PWN. Retrieved 14 November 2006.

- ^ "Śledztwa - Białystok" (in Polish). Archived from the original on January 7, 2005. Retrieved January 7, 2005.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) Polish Institute of National Remembrance. 16.10.03. From Internet Archive. - ^ (in Polish) Tygodnik Zamojskim[permanent dead link], 15 September 2004. Retrieved 28 November 2006.

- Encyklopedia Interia. Retrieved 28 November 2006.

- ^ Decision to commence investigation into Katyn Massacre Archived 2012-09-30 at the Wayback Machine, Małgorzata Kużniar-Plota, Departmental Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation, Warsaw 30 November 2004. "[...] some 250,000 Polish soldiers were taken into Soviet captivity. Some of them were released, and some escaped, but 125,400 prisoners were placed in NKVD prison camps in Kozelsk, Ostashkov, Starobelsk, Putivl, Yuzha, Oranki, Kozelshchina, and elsewhere."

- ISBN 978-0-415-33873-8. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-7146-5132-3. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ ISBN 978-3-86583-240-5. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ See telegrams: No. 317 Archived 2009-11-07 at the Wayback Machine of September 10: Schulenburg, the German ambassador in the Soviet Union, to the German Foreign Office. Moscow, 10 September 1939-9:40 p.m.; No. 371 Archived 2007-04-30 at the Wayback Machine of 16 September; No. 372 Archived 2007-04-30 at the Wayback Machine of 17 September Source: The Avalon Project at Yale Law School. Last accessed on 14 November 2006; (in Polish)1939 wrzesień 17, Moskwa Nota rządu sowieckiego nie przyjęta przez ambasadora Wacława Grzybowskiego (Note of the Soviet government to the Polish government on 17 September 1939 refused by Polish ambassador Wacław Grzybowski). Retrieved 15 November 2006.

- ^ Sanford, pp. 22–3; See also, Sanford, p 39: "The Soviet Union's invasion and occupation of Eastern Poland in September 1939 was a clear act of aggression in international law...But the Soviets did not declare war, nor did the Poles respond with a declaration of war. As a result there was confusion over the status of soldiers taken captive and whether they qualified for treatment as PoWs. Jurists consider that the absence of a formal declaration of war does not absolve a power from the obligations of civilised conduct towards PoWs. On the contrary, failure to do so makes those involved, both leaders and operational subordinates, liable to charges of War Crimes and Crimes against Humanity."

- ^ Sanford, p. 25 and p. 41.

- ^ "The grave unknown elsewhere or any time before ... Katyń – Kharkov – Mednoe", last retrieved on 10 December 2005. Article includes a note that it is based on a special edition of a "Historic Reference-Book for the Pilgrims to Katyń – Kharkow – Mednoe" by Jędrzej Tucholski

- ^

- ^ Decision to commence investigation into Katyn Massacre Archived 2012-09-30 at the Wayback Machine, Małgorzata Kużniar-Plota, Departmental Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation, Warsaw 30 November 2004

- ISBN 978-0-300-10851-4. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- ^ (in Russian) Катынь. Пленники необъявленной войны. сб.док. М., МФ "Демократия": 1999, сс.20–21, 208–210.

- ^ "The Katyn Diary of Leon Gladun" Archived 2019-03-11 at the Wayback Machine, last accessed on 19 December 2005, English translation of Polish document. See the entries on 25 December 1939 and 3 April 1940.

External links

- The epilogue to September 1939 – Polish soldiers in Soviet captivity - testimonies of Polish POW's in Soviet Union; "Chronicles of Terror"