Political history of Mysore and Coorg (1565–1760)

The

At the height of the Vijayanagara Empire, the Mysore and Coorg region was ruled by diverse

Mysore's expansions had been based on unstable alliances. When the alliances began to unravel, as they did during the next half-century, decay set in, presided over by politically and militarily inept kings. The Mughal governor, Nawab of Arcot, in a display of the still remaining reach of a

A common feature of all large regimes in the region during the period 1565–1760 is increased military fiscalism. This mode of creating income for the state consisted of extraction of tribute payments from local chiefs under threat of military action. It differed both from the more segmentary modes of preceding regimes and the more absolutist modes of succeeding ones—the latter achieved through direct tax collection from citizens. Another common feature of these regimes is the fragmentary historiography devoted to them, making broad generalizations difficult.

Poligars of Vijayanagara, 1565–1635

On 23 January 1565 the last

In the heyday of their rule, the kings of Vijayanagara had granted tracts of land in their realm to

.)The southern chiefs (sometimes called rajas, or "little kings") resisted on moral and political grounds as well. According to historian Burton Stein:

'Little kings', or rajas, never attained the legal independence of an aristocracy from both monarchs and the local people whom they ruled. The sovereign claims of would-be centralizing, South Indian rulers and the resources demanded in the name of that sovereignty diminished the resources which local chieftains used as a kind of royal largess; thus centralizing demands were opposed on moral as well as on political grounds by even quite modest chiefs.[9]

These chiefs came to be called

In 1577, more than a decade after the Battle of Talikota, Bijapur forces attacked again and overwhelmed all opposition along the western coast. They easily took Adoni, a former Vijayanagara stronghold, and subsequently attempted to take Penukonda, the new Vijayanagara capital.[11] (Map 3).) They were, however, repulsed by an army led by the Vijayanagara ruler's father-in-law, Jagadeva Raya, who had travelled north for the engagement from his base in Baramahal. For his services, his territories within the crumbling empire were expanded out to the Western Ghats, the mountain range running along the southwestern coast of India; a new capital was established in Channapatna[12] (Map 6.)

Soon the Wodeyars of Mysore (present-day

Bijapur, Marathas, Mughals, 1636–1687

In 1636, nearly 60 years after their defeat at Penukonda, the

In the western-central poligar regions, the

.)A new province, Caranatic-Bijapur-Balaghat, incorporating Kolar, Hoskote, Bangalore, and Sira, and situated above (or westwards of) the Eastern Ghats range, was added to the Sultanate of Bijapur and granted to Shahji as a jagir.[20] The possessions below the Ghats, such as Gingee and Vellore became part of another province, Carnatic-Bijapur-Payanghat, and Shahji was appointed its first governor.[20]

When Shahji died in 1664, his son

The successes of Bijapur and Shivaji were being watched with some alarm by their

Wodeyars of Mysore, 1610–1760

Although their own histories date the origins of the

By the time of the short-lived incumbency of Timmaraja II's son, Chama Raja IV—who, well into his 60s, ruled from 1572 to 1576—the Vijayanagara Empire had been dealt its fatal blow.

In 1638, the reins of power fell into the hands of the 23-year-old Kanthirava Narasaraja I, who had been adopted a few months earlier by the widow of Raja I.[32] Kanthirava was the first wodeyar of Mysore to create the symbols of royalty such as a royal mint, and coins named Kanthiraya (corrupted to "Canteroy") after himself.[32] These remained a part of Mysore's "current national money" well into the 18th century.[32]

After an unremarkable period of rule by short-lived incumbents, Kanthirava's 27-year-old great nephew,

gives the rains;Why should we, the ones who grow crops through hard labour, pay taxes to the king?[36]

The king used the stratagem of inviting over 400 monks to a grand feast at the famous Shaiva centre of Nanjanagudu. Upon its conclusion, he presented them with gifts and directed them to exit one at a time through a narrow lane where they were strangled by royal wrestlers who had been awaiting them.[36]

Around 1687 Chikka Devaraja purchased the city of

.)-

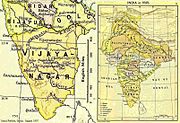

Map 5: Varying boundaries of Mysore from 1617 to 1799

-

Map 6: wodeyar Mysore and other petty kingdoms in the region c. 1625

-

Map 7: Mysore, c. 1704, during the reign of Chikka Devaraja

According to Sanjay Subrahmanyam, the

The early 18th century ushered in the rule of

Nayakas of Ikkeri and Kanara trade, 1565–1763

In the northwestern regions, according to Stein,

an even more impressive chiefly house arose in Vijayanagara times and came to enjoy an extensive sovereignty. These were the

Keladi chiefs who later founded the Nayaka kingdom of Ikkeri. At its greatest, the Ikkeri rajas controlled a territory nearly as large as the Vijayanagara heartland, some 20,000 square miles, extending about 180 miles south from Goa along the trade-rich Kanara coast.[40]

When

Onor (Modern

Located some 50 miles (80 km) south of Onor, and a few miles up the

.)Fifty miles south of Barcelore was Mangalore, the last of the Portuguese strongholds in Kanara; it was situated on the mouth of the

(Map 1.)As a ready source of rice, pepper, and teak, the Kanara coast was important to the Estado.[45] For much of the 16th century, Portuguese had been able to negotiate favourable terms of trade with the weak principalities that constituted the Kanara coast.[45] Towards the end of the century, the Nayaka ruler of Keladi (and Ikkeri), Venkatappa Nayaka (r. 1592–1629), and his successors, Virabhadra Nayaka (r. 1629–1645) and Shivappa Nayaka (r. 1645–1660) forced a revision of the previous trade treaties.[45] By the 1630s, the Portuguese had agreed to buy pepper at market rates and the rulers of Ikkeri had been permitted two voyages per year without the purchase of a cartaz (a pass for Portuguese protection) as well as annual importation of twelve duty-free horses.[45] When the last king of Vijayanagara sought refuge in his realms, Shivappa Nayaka set him up at Belur and Sakkarepatna, and later mounted an unsuccessful siege of

Before the treaty could be implemented, though, Somashkar Nayaka died and was succeeded by an infant grandson Basava Nayaka, his succession disputed by the Queen Mother, who favoured another claimant, Timmaya Nayaka.

Subahdars of Sira, 1689–1760

A

The capital of the province, Sira town, prospered most under Dilavar Khan and expanded in size to accommodate 50,000 homes.

Earlier, after the

-

Map 9: An 1897 map of Shimoga district showing Ikkeri and Keladi in Sagartaluqon the west (in orange)

-

Map 10: The Mughal province of Sira shown in a map of South India at the time of the Anglo-French Wars in the Carnatic, 1746–1760.

-

Map 11: Map of Coorg province c. 1897

Until the mid-17th century, both village- and district (

Rajas of Coorg, mid-16th century – 1768

Although, Rājendranāme, a "royal" genealogy of the rulers of

| ||||||||||||||||

By the late 17th century, the rajas of Coorg had created an "aggressive and independent" state.

In 1724, major hostilities resumed between Coorg and Mysore.

More than a century earlier,

Dodda Virappa evinced throughout his long and vigorous reign an unconquerable spirit, and though surrounded by powerful neighbours, neither the number nor the strength of this enemies seems to have relaxed his courage or damped his enterprise. He died in 1736, 78 years old. Two of his wives ascended the funeral pile with the dead body of the Raja.[66]

Assessment: the period and its historiography

From the mid-15th century to the mid-18th century rulers of states in southern India commenced financing wars on a different footing than had their predecessors.[67] According to historian Burton Stein, all the rulers of the Mysore and Coorg region—the Vijayanagara emperors, the Wodeyars of Mysore, the Nayakas of Ikkeri, the Subahdars of Sira, and the Rajas of Coorg—fall to some degree under this category.[67] A similar political system, referred to as "military fiscalism" by French historian Martin Wolfe, took hold in Europe between the 15th and 17th centuries.[67] During this time, according to Wolfe, most regimes in Western Europe emerged from the aristocracy to become absolute monarchies; they simultaneously reduced their dependence on the aristocracy by expanding the tax base and developing an extensive tax collection structure.[67] In Stein's words,

Previously resistant aristocracies were eventually won over in early modern Europe by being offered state offices and honours and by being protected in their patrimonial wealth, but this was only after monarchies had proven their ability to defeat antiquated feudal forces and had found alternative resources in cities and from trade.[67]

In southern India, none of the pre-1760 regimes were able to achieve the "fiscal absolutism" of their European contemporaries.[68] Local chieftains, who had close ties with their social groups, and who had only recently risen from them, opposed the excessive monetary demands of a more powerful regional ruler.[68] Consequently, the larger states of this period in southern India, were not able to entirely change their mode of creating wealth from one of extracting tribute payments, which were seldom regular, to that of direct collection of taxes by government officials.[68] Extorting tribute under threat of military action, according to Stein, is not true "military fiscalism," although it is a means of approaching it.[68] This partial or limited military fiscalism began during the Vijayanagara Empire, setting the latter apart from the more "segmentary" regimes that had preceded it,[68] and was a prominent feature of all regimes during the period 1565–1760;[68] true military fiscalism was not achieved in the region until the rule of Tipu Sultan in the 1780s.[68]

Stein's formulation has been criticized by historian

A major problem attendant on such generalisations by modern historians concerning pre-1760 Mysore is, however, the paucity of documentation on this older 'Old Regime'.[69]

The first explicit History of Mysore in English is Historical Sketches of the South of India, in an attempt to trace the History of Mysoor by

A

The earliest manuscript offering clues to governance and military conflict in the pre-1760 Mysore, seems to be Dias (

See also

- Political history of Mysore and Coorg (1761–1799)

- Political history of Mysore and Coorg (1800–1947)

- Company rule in India

- Princely state

Notes

- ^ The austere, grandiose site of Hampi was the last capital of the last great Hindu Kingdom of Vijayanagar. Its fabulously rich princes built Dravidian temples and palaces which won the admiration of travellers between the 14th and 16th centuries. Conquered by the Deccan Muslim confederacy in 1565, the city was pillaged over a period of six months before being abandoned." From the brief description, UNESCO World Heritage List; India, Group of Monuments at Hampi.[1]

- ^ Krishnappa is said to have sent his able minister and chief agent of his consolidation of power in Madurai, Ariyanatha Mudaliar, with a large force to join Rama Raja as he marched northward to meet the assembled Muslim force on the Krishna River, eighty miles north of Vijayanagara. There, on the south bank of the river, in late January 1565, the Vijayanagara armies were at last decisively defeated, Rama Raja and many of his kinsmen and dependants were killed and the city opened to sacking by a combination of Golkonda soldiers and poligars from nearer to Vijayanagara. Rama Raja’s warrior brother Tirumala survived the battle and brought the remnants of the once great army to Vijayanagara. Soon after, at the approach of the celebrating Golkonda army, he sought a place of greater security. This may have been Penukonda, a longtime royal stronghold, 120 miles and eight days’ journey south-east of Vijayanagara; others believe that Tirumala took refuge behind the high walls of Venkatesvara’s temple at Tirupati, still further away. The Muslim confederates immediately retrieved most of the territory that had been seized by Rama Raja during the previous twenty years, but certain places remained in Hindu hands for a longer time: Adoni was held until 1568 and Dharwar and Bankapur until 1573. After looting and a brief occupation, Vijayanagara was left to a future of neglect which has only been lifted recently by archaeologists and art historians working at Hampi.[3]

- ^ Less than a year later, the sultanate confederates fell out. Bijapur attacked Ahmadnagar and Golkonda joined forces with the latter. Some contemporary accounts even relate how Tirumala was approached to become a co-belligerent against Bijapur in the resurgent struggles! This last scheme did not materialise, leaving Tirumala free to commence his rule of the kingdom, nominally as regent, for Sadasivaraya was still alive and remained so until perhaps 1575. Vijayanagara appears to have been reoccupied by Tirumala for a time after his victors departed, but his efforts to repopulate the city were frustrated by attacks upon it by Bijapur soldiers who might have been invited there by Peda Tirumala, Rama Raja’s son, who opposed his uncle’s seizure of the regency. Tirumala may also have decided to leave Vijayanagara because of the support that Peda Tirumala, his nephew, enjoyed there. In any case, he moved back to Penukonda where the court was to be.[3]

- ^ Located on an island in the Kaveri, the great sacred south Indian river, the fortress of Srirangapattana became the capital of the Hindu Wodeyar dynasty of Mysore in 1610. A foundation myth tells of a miraculous milch cow from whom milk flowed spontaneously into a pit and how the god Ranganatha appeared to the Kartar, or Raja, in a dream, instructing him to build a temple in his honour on the site (1). Another story, in the Sthalapurana, relates how the god came to reside on the island at the request of the river goddess. The myths reflect the auspicious nature of the location, whose situation made a potent source of sacred power, the power to which aspiring rulers sought access over the centuries. It is little wonder, then, that Seringapatam, as it is more familiarly known, remained Mysore's capital, through fluctuating fortunes, until its final conquest by the British in 1799. In more mundane terms, the establishment of Wodeyar power had been facilitated by the decline of the empire of Vijayanagara, whose suzerainty Mysore continued to acknowledge for another fifty-eight years. Successors in the region to the hegemony of the Colas and the Hoysalas, the rulers of this great Hindu dynasty, held sway in the south for over two hundred years.[6]

- Virasaivasinto prominence.

- ^ Devendra, or Indra, is the Vedic Hindu god of war, thunder, and rain.

- Sufisaint.

- ^ "In India: The process of assessing the government land-tax over a specific area."[57]

Citations

- ^ UNESCO & World Heritage Convention 1986.

- ^ Black 1996, p. 22.

- ^ a b c Stein 1987, pp. 118–119.

- ^ a b Subrahmanyam 2002, p. 133.

- ^ a b Stein 1987, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Brittlebank 1997, p. 17.

- ^ a b c d e Simmons 2019, p. 6.

- ^ a b c Michell 1995, p. 18.

- ^ Stein 1985, p. 392.

- ^ Robb 2011, p. 66.

- ^ Michell & Zebrowski 1999, pp. 17–18.

- ^ Subrahmanyam 2012, p. 69.

- ^ Stein 2013, p. 198.

- ^ a b c Stein 1987, p. 83.

- ^ a b c Robb 2011, pp. 103–104.

- ^ Subrahmanyam 2002, p. 33–35.

- ^ Stein 1987, p. 123.

- ^ a b c Ahmed 2011, p. 315.

- ^ a b Asher & Talbot 2006, p. 175.

- ^ a b c Roy 2015, p. 74.

- ^ Hunt & Stern 2015, p. 9.

- ^ a b Roy 2013, p. 33.

- ^ a b Gordon 2007, p. 92.

- ^ a b c d e f Ravishankar 2018, p. 360.

- ^ Knipe 2015, p. 40.

- ^ Kamdar 2018, p. 41.

- ^ a b c d e f Stein 1987, p. 82.

- ^ Manor 1975, p. 33.

- ^ Ramusack 2004, p. 28.

- ^ a b Michell 1995, pp. 17–.

- ^ Simmons 2019, p. 126.

- ^ a b c d e f g Simmons 2019, pp. 6–8.

- ^ a b c d e Subrahmanyam 1989, pp. 208–209.

- ^ Bandyopadhyay 2004, p. 33.

- ^ a b c Stein 1985, pp. 400–401.

- ^ a b Nagaraj 2003, pp. 378–379.

- ^ a b c d Subrahmanyam 1989, p. 212.

- ^ a b c d e Subrahmanyam 1989, p. 213.

- ^ Rice 1897a, p. 370.

- ^ Stein 1987, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Disney 1978, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d e f Disney 1978, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e f g Disney 1978, p. 5.

- ^ Ames 2000, p. 11.

- ^ a b c d e Ames 2000, p. 157.

- ^ Ames 2000, pp. 157–158.

- ^ a b Ames 2000, pp. 158–159.

- ^ a b Ames 2000, p. 159.

- ^ a b Ames 2000, p. 160.

- ^ a b c d e Rice 1908, pp. 175–176.

- ^ Rice 1908, p. 166.

- ^ Rice 1908, p. 19.

- ^ a b c d e f g Rice 1897b, p. 166.

- ^ Rice 1897b, p. 521.

- ^ a b c d e f Rice 1897a, p. 589.

- ^ a b Rice 1897a, pp. 574–575.

- ^ "Settlement (n), 10", Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, retrieved 24 October 2020

- ^ a b c d Rice 1897a, pp. 589–590.

- ^ a b c Rice 1878, p. 99.

- ^ a b c d e f Subrahmanyam 1989, p. 99.

- ^ a b Rice 1878, p. 105.

- ^ a b c d Rice 1878, p. 106.

- ^ a b c d Subrahmanyam 1989, pp. 217–218.

- ^ a b c d e Subrahmanyam 1989, pp. 218–219.

- ^ Subrahmanyam 1989, p. 220.

- ^ Rice 1878, p. 107.

- ^ a b c d e Stein 1985, pp. 391–392.

- ^ a b c d e f g Stein 1985, pp. 392–393.

- ^ Stein 1987, p. 206.

- ^ Wilks 1811, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e Subrahmanyam 1989, p. 206.

- ^ Ikegame 2007, p. 17.

- ^ Nair 2006, pp. 139–140.

- ^ Bhagavan 2008, p. 887.

- ^ Subrahmanyam 1989, pp. 215–216.

- ^ East India Company 1800.

- ^ Wilks 1805.

- ^ Michaud 1809.

- ^ Buchanan 1807.

- ^ Rice 1879.

- ^ Digby 1878.

Sources used

Secondary sources

- Richter, G (1870). Manual of Coorg- A Gazetteer of the natural features of the country and the social and political condition of its inhabitants. Mangalore: C Stolz, Basel Mission Book Depository. ISBN 9781333863098.

- Ahmed, Farooqui Salma (2011), A Comprehensive History of Medieval India: From Twelfth to the Mid-Eighteenth Century, Pearson Education, ISBN 978-81-317-3202-1

- Ames, Glenn J. (2000), Renascent Empire? The House of Braganza and the Quest for Stability in Portuguese Monsoon Asia, C. 1640–1683, Amsterdam University Press. p. 262, ISBN 90-5356-382-2

- Asher, Catherine B.; Talbot, Cynthia (2006), India Before Europe, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-80904-7

- Bandyopadhyay, Sekhar (2004), From Plassey to Partition: A History of Modern India, New Delhi and London: Orient Longmans. pp. xx, 548., ISBN 81-250-2596-0

- Bhagavan, Manu (2008), "Princely States and the Hindu Imaginary: Exploring the Cartography of Hindu Nationalism in Colonial India", The Journal of Asian Studies, 67 (3): 881–915, S2CID 162507058

- Black, Jeremy (1996), The Cambridge Illustrated Atlas of Warfare: Renaissance to Revolution, 1492-1792, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-47033-9

- Brittlebank, Kate (1997), Tipu Sultan's Search for Legitimacy: Islam and Kingship in a Hindu Domain, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-563977-3

- Disney, A. R. (1978), Twilight of the Pepper Empire: Portuguese Trade in Southwest India in the Early Seventeenth Century (Harvard Historical Studies), Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. p. 222, ISBN 0-674-91429-5

- Gordon, Stewart (2007), The Marathas 1600-1818, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-03316-9

- Hunt, Margaret R.; Stern, Philip J. (2015), The English East India Company at the Height of Mughal Expansion: A Soldier's Diary of the 1689 Siege of Bombay, with Related Documents, Bedford/St. Martin's, pp. 9–, ISBN 978-1-319-04948-5

- Ikegame, Aya (2007), "The capital of rajadharma: modern space and religion in colonial Mysore", International Journal of Asian Studies, 4 (1): 15–44, S2CID 145718135

- Kamdar, Mira (2018), India in the 21st Century: What Everyone Needs to Know, Oxford University Press, pp. 41–, ISBN 978-0-19-997360-6

- Knipe, David M. (2015), Vedic Voices: Intimate Narratives of a Living Andhra Tradition, Oxford University Press, pp. 40–, ISBN 978-0-19-026673-8

- Manor, James (1975), "Princely Mysore before the Storm: The State-Level Political System of India's Model State, 1920–1936", Modern Asian Studies, 9 (1): 31–58, S2CID 146415366

- Michell, George (1995), Architecture and Art of Southern India: Vijayanagara and the successor states: 1350–1750, Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-44110-2

- Michell, George; Zebrowski, Mark (1999), Architecture and Art of the Deccan Sultanates, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-56321-5

- Nagaraj, D. R. (2003), "Critical Tensions in the History of Kannada Literary Culture", in Pollock, Sheldon (ed.), Literary Cultures in History: Reconstructions from South Asia, Berkeley and London: University of California Press. p. 1066, pp. 323–383, ISBN 9780520228214

- Nair, Janaki (2006), "Tipu Sultan, History Painting and the Battle for 'Perspective'", Studies in History, 22 (1): 97–143, S2CID 159522616

- Ramusack, Barbara (2004), The Indian Princes and their States (The New Cambridge History of India), Cambridge and London: Cambridge University Press. p. 324, ISBN 0-521-03989-4

- Ravishankar, Chinya V. (2018), Sons of Sarasvati: Late Exemplars of the Indian Intellectual Tradition, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-1-4384-7185-3

- Rice, Lewis (1878), "History of Coorg", Mysore and Coorg, A Gazetteer compiled for the Government, Volume 3, Coorg, Bangalore: Mysore Government Press. p. 427

- Rice, Lewis (1897a), "History of Mysore", Mysore: A Gazetteer Compiled for the Government, Volume I, Mysore in General, Westminster: Archibald Constable and Company. pp. xix, 834

- Rice, Lewis (1897b), "History of Districts", Mysore: A Gazetteer Compiled for the Government, Volume II, Mysore, By Districts, Westminster: Archibald Constable and Company. pp. xii, 581

- Rice, Lewis (1908), "History of Mysore and Coorg", Imperial Gazetteer of India, Provincial Series: Mysore and Coorg, Calcutta: Superintendent of Government Printing. pp. xvii, 365, one map.

- Robb, Peter (2011), A History of India, Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-230-34424-2

- Roy, Kaushik (2015), Military Manpower, Armies and Warfare in South Asia, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-317-32128-6

- Roy, Tirthankar (2013), An Economic History of Early Modern India, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-135-04787-0

- Simmons, Caleb (2019), Devotional Sovereignty: Kingship and Religion in India, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-008890-3

- S2CID 154665616

- ISBN 0-521-26693-9

- ISBN 978-1-136-10234-9

- Subrahmanyam, Sanjay (1989), "Warfare and state finance in Wodeyar Mysore, 1724–25: A missionary perspective", Indian Economic and Social History Review, 26 (2): 203–233, S2CID 145180609

- Subrahmanyam, Sanjay (2002), The Political Economy of Commerce: Southern India 1500–1650, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-89226-1

- Subrahmanyam, Sanjay (2012), Courtly Encounters, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-07168-1

- UNESCO; World Heritage Convention (1986), "Group of Monuments at Hampi", World Heritage List, United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization, retrieved 28 October 2020

Primary sources

- Buchanan, Francis (1807), A Journey from Madras Through the Countries of Mysore, Canara and Malabar: Performed Under the Orders of the Most Noble the Marquis Wellesley, Governor General of India, ... in the Dominions of the Rajah of Mysore : in Three Volumes, London: Cadell and Davies

- Dias, Joachim, SJ (1725), Relaçāo das couzas succedidas neste reino do Maȳsur desde mayo de 1724 athe agosto de 1725 ("Relation of the events occurring in this kingdom of Mysore between May 1724 and August 1725"), Lisbon: Bibloteca Nacional de Lisboa, Fundo Geral, Códice 178. fls. 40–51v)

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - Digby, William (1878), The Famine Campaign in Southern India (Madras and Bombay Presidencies and Province of Mysore) 1876–1878, In Two Volumes, London: Longmans, Green, and Co., Volume 1, pp. 515, Volume 2, pp. 492

- East India Company (1800), Copies and Extracts of Advices to and from India, Relative to the Cause, Progress and Successful Termination of the War with the Late Tippoo Sultaun, ..., Printed for the use of the Proprietors of East India Stock

- Michaud, Joseph-François, SJ (1809), Histoire des progrès et de la chute de l'empire de Mysore, sous les règnes d'Hyder-Aly et de Tippoo-Saïb: contenant l'historique des guerres des souverains de Mysore avec les Anglais et les différentes puissances de l'Inde, Paris: Chez Guiget et Cie.)

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - Rice, Lewis (1879), Mysore Inscriptions: Translated for Government, Bangalore: Mysore Government Press. p. 336

- Wilks, Mark (1805), Report on the Interior Administration, Resources, and Expenditure of the Government of Mysoor, Fort William: By Order of the Governor General in Council. p. 161

- Wilks, Mark (1811) [1st edition: 1811, volume 1; 1817, volumes 2 and 3; second edition: 1869], Historical Sketches of the South of India in an attempt to trace the History of Mysoor, Second Edition, Madras: Higginbotham and Co. pp. xxxii, 527