Pope Gregory I

| Patronage | Musicians, singers, students, and teachers |

|---|---|

| Other popes named Gregory | |

Pope Gregory I (

A

Throughout the Middle Ages, he was known as "the Father of Christian Worship" because of his exceptional efforts in revising the Roman worship of his day.

Gregory is one of the

Early life

Gregory was born around 540

Gregory was born into a wealthy noble Roman family with close connections to the church. His father, Gordianus, a patrician[1] who served as a senator and for a time was the Prefect of the City of Rome,[12] also held the position of Regionarius in the church, though nothing further is known about that position. Gregory's mother, Silvia, was well-born, and had a married sister, Pateria, in Sicily. His mother and two paternal aunts are honored by Catholic and Orthodox churches as saints.[12][4] Gregory's grandfather had been Pope Felix III,[e] the nominee of the Gothic king, Theodoric.[13] Gregory's election to the throne of St. Peter made his family the most distinguished clerical dynasty of the period.[14]

The family owned and resided in a

Gregory was born into a period of upheaval in Italy. From 542 the so-called Plague of Justinian swept through the provinces of the empire, including Italy. The plague caused famine, panic, and sometimes rioting. In some parts of the country, over a third of the population was wiped out or destroyed, with heavy spiritual and emotional effects on the people of the empire.[19] Politically, although the Western Roman Empire had long since vanished in favor of the Gothic kings of Italy, during the 540s Italy was gradually retaken from the Goths by Justinian I, emperor of the Eastern Roman Empire ruling from Constantinople. As the fighting was mainly in the north, the young Gregory probably saw little of it. Totila sacked and vacated Rome in 546, destroying most of its population, but in 549 he invited those who were still alive to return to the empty and ruined streets. It has been hypothesized that young Gregory and his parents retired during that intermission to their Sicilian estates, to return in 549.[20] The war was over in Rome by 552, and a subsequent invasion of the Franks was defeated in 554. After that, there was peace in Italy, and the appearance of restoration, except that the central government now resided in Constantinople.[citation needed]

Like most young men of his position in Roman society, Gregory was well educated, learning grammar, rhetoric, the sciences, literature, and law; he excelled in all these fields.[12] Gregory of Tours reported that "in grammar, dialectic and rhetoric ... he was second to none".[21] He wrote correct Latin but did not read or write Greek. He knew Latin authors, natural science, history, mathematics and music and had such a "fluency with imperial law" that he may have trained in it "as a preparation for a career in public life".[21] Indeed, he became a government official, advancing quickly in rank to become, like his father, Prefect of Rome, the highest civil office in the city, when only thirty-three years old.[12]

The monks of the

In the modern era, Gregory is often depicted as a man at the border, poised between the Roman and Germanic worlds, between East and West, and above all, perhaps, between the ancient and medieval epochs.[23]

Monastic years

On his father's death, Gregory converted his family villa into a monastery dedicated to Andrew the Apostle (after his death it was rededicated as San Gregorio Magno al Celio). In his life of contemplation, Gregory concluded that "in that silence of the heart, while we keep watch within through contemplation, we are as if asleep to all things that are without."[24]

Gregory had a deep respect for the monastic life and particularly the vow of poverty. Thus, when it came to light that a monk lying on his death bed had stolen three gold pieces, Gregory, as a remedial punishment, forced the monk to die alone, then threw his body and coins on a manure heap to rot with a condemnation, "Take your money with you to perdition." Gregory believed that punishment of sins can begin, even in this life before death.

Eventually, Pope Pelagius II ordained Gregory a deacon and solicited his help in trying to heal the schism of the Three Chapters in northern Italy. However, this schism was not healed until well after Gregory was gone.[27]

Apocrisiariate (579–585)

In 579, Pelagius II chose Gregory as his

According to Ekonomou, "if Gregory's principal task was to plead Rome's cause before the emperor, there seems to have been little left for him to do once imperial policy toward Italy became evident. Papal representatives who pressed their claims with excessive vigor could quickly become a nuisance and find themselves excluded from the imperial presence altogether".

Gregory's theological disputes with Patriarch Eutychius would leave a "bitter taste for the theological speculation of the East" with Gregory that continued to influence him well into his own papacy.

Gregory left Constantinople for Rome in 585, returning to his monastery on the

Controversy with Eutychius

In Constantinople, Gregory took issue with the aged

Papacy

Gregory was more inclined to remain retired into the monastic lifestyle of contemplation.[37] In texts of all genres, especially those produced in his first year as pope, Gregory bemoaned the burden of office and mourned the loss of the undisturbed life of prayer he had once enjoyed as a monk.[38] When he became pope in 590, among his first acts was writing a series of letters disavowing any ambition to the throne of Peter and praising the contemplative life of the monks. At that time, for various reasons, the Holy See had not exerted effective leadership in the West since the pontificate of Gelasius I. The episcopacy in Gaul was drawn from the great territorial families, and identified with them: the parochial horizon of Gregory's contemporary, Gregory of Tours, may be considered typical; in Visigothic Spain the bishops had little contact with Rome; in Italy the territories which had de facto fallen under the administration of the papacy were beset by the violent Lombard dukes and the rivalry of the Byzantines in the Exarchate of Ravenna and in the south.[citation needed]

Pope Gregory had strong convictions on missions: "Almighty God places good men in authority that He may impart through them the gifts of His mercy to their subjects. And this we find to be the case with the British over whom you have been appointed to rule, that through the blessings bestowed on you the blessings of heaven might be bestowed on your people also."[39] He is credited with re-energizing the Church's missionary work among the non-Christian peoples of northern Europe. He is most famous for sending a mission, often called the Gregorian mission, under Augustine of Canterbury, prior of Saint Andrew's, where he had perhaps succeeded Gregory, to evangelize the pagan Anglo-Saxons of Britain. It seems that the pope had never forgotten the Anglo-Saxon slaves whom he had once seen in the Roman Forum.[40] The mission was successful, and it was from England that missionaries later set out for the Netherlands and Germany. The preaching of non-heretical Christian faith and the elimination of all deviations from it was a key element in Gregory's worldview, and it constituted one of the major continuing policies of his pontificate.[41] Pope Gregory the Great urged his followers on the value of bathing as a bodily need.[42]

It is said he was declared a saint immediately after his death by "popular acclamation".[1]

In his official documents, Gregory was the first to make extensive use of the term "

Alms

The Church had a practice from early times of passing on a large portion of the donations it received from its members as alms. As pope, Gregory did his utmost to encourage that high standard among church personnel.[citation needed] Gregory is known for his extensive administrative system of charitable relief of the poor at Rome. The poor were predominantly refugees from the incursions of the Lombards. The philosophy under which he devised this system is that the wealth belonged to the poor and the church was only its steward. He received lavish donations from the wealthy families of Rome, who, following his own example, were eager, by doing so, to expiate their sins. He gave alms equally as lavishly both individually and en masse. He wrote in letters:[44] "I have frequently charged you ... to act as my representative ... to relieve the poor in their distress" and "I hold the office of steward to the property of the poor".

In Gregory's time, the Church in Rome received donations of many different kinds:

The circumstances in which Gregory became pope in 590 were of ruination. The Lombards held the greater part of Italy. Their depredations had brought the economy to a standstill. They camped nearly at the gates of Rome. The city itself was crowded with refugees from all walks of life, who lived in the streets and had few of the necessities of life. The seat of government was far from Rome in Constantinople and appeared unable to undertake the relief of Italy. The pope had sent emissaries, including Gregory, asking for assistance, to no avail.[citation needed]

In 590, Gregory could wait for Constantinople no longer. He organized the resources of the church into an administration for general relief. In doing so he evidenced a talent for and intuitive understanding of the principles of accounting, which was not to be invented for centuries. The church already had basic accounting documents: every

Gregory began by aggressively requiring his churchmen to seek out and relieve needy persons and reprimanded them if they did not. In a letter to a subordinate in Sicily he wrote: "I asked you most of all to take care of the poor. And if you knew of people in poverty, you should have pointed them out ... I desire that you give the woman, Pateria, forty solidi for the children's shoes and forty bushels of grain".[47] Soon he was replacing administrators who would not cooperate with those who would and at the same time adding more in a build-up to a great plan that he had in mind. He understood that expenses must be matched by income. To pay for his increased expenses he liquidated the investment property and paid the expenses in cash according to a budget recorded in the polyptici. The churchmen were paid four times a year and also personally given a golden coin for their trouble.[48]

Money, however, was no substitute for food in a city that was on the brink of famine. Even the wealthy were going hungry in their villas.[citation needed] The church now owned between 1,300 and 1,800 square miles (3,400 and 4,700 km2) of revenue-generating farmland divided into large sections called patrimonia. It produced goods of all kinds, which were sold, but Gregory intervened and had the goods shipped to Rome for distribution in the diaconia. He gave orders to step up production, set quotas and put an administrative structure in place to carry it out. At the bottom was the rusticus who produced the goods. Some rustici were or owned slaves. He turned over part of his produce to a conductor from whom he leased the land. The latter reported to an actionarius, who reported to a defensor, who reported to a rector. Grain, wine, cheese, meat, fish, and oil began to arrive at Rome in large quantities, where it was given away for nothing as alms.[49]

Distributions to qualified persons were monthly. However, a certain proportion of the population lived in the streets or were too ill or infirm to pick up their monthly food supply. To them Gregory sent out a small army of charitable persons, mainly monks, every morning with prepared food. It is said that he would not dine until the indigent were fed. When he did dine he shared the family table, which he had saved (and which still exists), with 12 indigent guests. To the needy living in wealthy homes he sent meals he had cooked with his own hands as gifts to spare them the indignity of receiving charity. Hearing of the death of an indigent in a back room he was depressed for days, entertaining for a time the conceit that he had failed in his duty and was a murderer.[48]

These and other good deeds and charitable frame of mind completely won the hearts and minds of the Roman people. They now looked to the papacy for government, ignoring the state at Constantinople. The office of urban prefect went without candidates. From the time of Gregory the Great to the rise of Italian nationalism the papacy was the most influential presence in Italy.[citation needed]

Works

Liturgical reforms

John the Deacon wrote that Pope Gregory I made a general revision of the liturgy of the

Sacramentaries directly influenced by Gregorian reforms are referred to as Sacrementaria Gregoriana. Roman and other Western liturgies since this era have a number of prayers that change to reflect the feast or liturgical season; these variations are visible in the collects and prefaces as well as in the Roman Canon itself.[citation needed]

Divine Liturgy of the Presanctified Gifts

In the

Gregorian chant

The mainstream form of Western

Writings

Gregory is commonly credited with founding the medieval papacy and so many attribute the beginning of medieval spirituality to him.[54] Gregory is the only pope between the fifth and the eleventh centuries whose correspondence and writings have survived enough to form a comprehensive corpus. Some of his writings are:

- Moralia in Job. This is one of the longest patristic works. It was possibly finished as early as 591. It is based on talks Gregory gave on the Book of Job to his 'brethren' who accompanied him to Constantinople. The work as we have it is the result of Gregory's revision and completion of it soon after his accession to the papal office.[55]

- Pastoral Care (Liber regulae pastoralis), in which he contrasted the role of bishops as pastors of their flock with their position as nobles of the church: the definitive statement of the nature of the episcopal office. This was probably begun before his election as pope and finished in 591.

- Dialogues, a collection of four books of miracles, signs, wonders, and healings done by the holy men, mostly monastic, of sixth-century Italy, with the second book entirely devoted to a popular life of Saint Benedict.[56]

- Sermons, including:

- The 22 Homilae in Hiezechielem (Homilies on Ezekiel), dealing with Ezekiel 1.1–4.3 in Book One, and Ezekiel 40 in Book 2. These were preached during 592–593, the years that the Lombards besieged Rome, and contain some of Gregory's most profound mystical teachings. They were revised eight years later.

- The Homilae xl in Evangelia (Forty Homilies on the Gospels) for the liturgical year, delivered during 591 and 592, which were seemingly finished by 593. A papyrus fragment from this codex survives in the British Museum, London, UK.[57]

- Expositio in Canticis Canticorum. Only two of these sermons on the Song of Songs survive, discussing the text up to Song 1.9.

- In Librum primum regum expositio (Commentary on 1 Kings), which scholars now think that this is a work by 12th century monk, Peter of Cava, who used no longer extant Gregorian material.

- Copies of some 854 letters have survived. During Gregory's time, copies of papal letters were made by scribes into a Registrum (Register), which was then kept in the scrinium. It is known that in the 9th century, when John the Deacon composed his Life of Gregory, the Registrum of Gregory's letters was formed of 14 papyrus rolls (though it is difficult to estimate how many letters this may have represented). Though these original rolls are now lost, the 854 letters have survived in copies made at various later times, the largest single batch of 686 letters being made by order of Adrian I (772–795).[55] The majority of the copies, dating from the 10th to the 15th century, are stored in the Vatican Library.[58]

Gregory wrote over 850 letters in the last 13 years of his life (590–604) that give us an accurate picture of his work.[59] A truly autobiographical presentation is nearly impossible for Gregory. The development of his mind and personality remains purely speculative in nature.[60]

Opinions of the writings of Gregory vary. "His character strikes us as an ambiguous and enigmatic one", the Jewish Canadian–American popularist

Identification of three figures in the Gospels

Gregory was among those who identified

Iconography

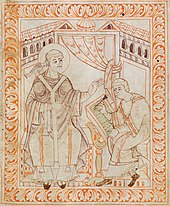

In art Gregory is usually shown in full pontifical robes with the

Ribera's oil painting of Saint Gregory the Great (c. 1614) is from the Giustiniani collection. The painting is conserved in the Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, Rome. The face of Gregory is a caricature of the features described by John the Deacon: total baldness, outthrust chin, beak-like nose, whereas John had described partial baldness, a mildly protruding chin, slightly aquiline nose and strikingly good looks. In this picture also Gregory has his monastic back on the world, which the real Gregory, despite his reclusive intent, was seldom allowed to have.[citation needed]

This scene is shown as a version of the traditional

The late medieval subject of the

Famous quotes and anecdotes

- Non Angli, sed angeli, si forent Christiani.– "They are not Angles, but angels, if they were Christian".[72] Aphorism, summarizing words reported to have been spoken by Gregory when he first encountered pale-skinned English boys at a slave market, sparking his dispatch of St. Augustine of Canterbury to England to convert the English, according to Bede.[73] He said: "Well named, for they have angelic faces and ought to be co-heirs with the angels in heaven."[74] Discovering that their province was Deira, he went on to add that they would be rescued de ira, "from the wrath", and that their king was named Aella, Alleluia, he said.[k]

- Locusta, literally, "locust". However, the word sounds very much like "loco sta", meaning, "Stay in place!" Gregory himself wanted to go to England as a missionary and started out for there. On the fourth day of the journey, as they stopped for lunch, a locust landed on the edge of the Bible which Gregory was reading. He exclaimed, locusta! (locust). Reflecting on it, he understood it as a sign from Heaven whereby God wanted him to loco sta, that is, remain in his own place. Within the hour an emissary of the pope[l] arrived to recall him.[74]

- "I beg that you will not take the present amiss. For anything, however trifling, which is offered from the prosperity of St. Peter should be regarded as a great blessing, seeing that he will have power both to bestow on you greater things, and to hold out to you eternal benefits with Almighty God."[This quote needs a citation]

- Pro cuius amore in eius eloquio nec mihi parco – "For the love of whom (God) I do not spare myself from His Word."[75][76] The sense is that since the creator of the human race and redeemer of him unworthy gave him the power of the tongue so that he could witness, what kind of a witness would he be if he did not use it but preferred to speak infirmly?

- "For the place of heretics is very pride itself...for the place of the wicked is pride just as conversely humility is the place of the good."[41]

- "Whoever calls himself universal bishop, or desires this title, is, by his pride, the precursor to the Antichrist."[77]

- Non enim pro locis res, sed pro bonis rebus loca amanda sunt – "Things are not to be loved for the sake of a place, but places are to be loved for the sake of their good things." When Augustine asked whether to use Roman or Gallican customs in the Mass in England, Gregory said, in paraphrase, that it was not the place that imparted goodness but good things that graced the place, and it was more important to be pleasing to the Almighty. They should pick out what was "pia", "religiosa" and "recta" from any church whatever and set that down before the English minds as practice.[78]

- "For the rule of justice and reason suggests that one who desires his own orders to be observed by his successors should undoubtedly keep the will and ordinances of his predecessor."[79] In his letters, Gregory often emphasized the importance of giving proper deference to last wills and testaments, and of respecting property rights.

- "Compassion should be shown first to the faithful and afterwards to the enemies of the church."[80]

- "At length being anxious to avoid all these inconveniences, I sought the haven of the monastery... For as the vessel that is negligently moored, is very often (when the storm waxes violent) tossed by the water out of its shelter on the safest shore, so under the cloak of the Ecclesiastical office, I found myself plunged on a sudden in a sea of secular matters, and because I had not held fast the tranquillity of the monastery when in possession, I learnt by losing it, how closely it should have been held."[81] In Moralia, sive Expositio in Job ("Commentary on Job," also known as Magna Moralia), Gregory describes to the Bishop Leander the circumstances under which he became a monk.

- "Illiterate men can contemplate in the lines of a picture what they cannot learn by means of the written word."[82]

- Age quod agis (Do what you are doing).[83] Through the centuries, this would become a repeated maxim of Catholic mystics and spiritual directors encouraging one to keep focus on what one is doing in trying to serve the Lord.

- "Repentance is weeping for what one has done and not doing what one weeps for."[84]

Memorials

Relics

The relics of Saint Gregory are enshrined in St. Peter's Basilica in Rome.[85]

Lives

In Britain, appreciation for Gregory remained strong even after his death, with him being called Gregorius noster ("our Gregory") by the British.[86] It was in Britain, at a monastery in Whitby, that the first full-length life of Gregory was written, c. 713, by a monk or, possibly, a nun.[87] Appreciation of Gregory in Rome and Italy itself, however, did not come until later. The first vita of Gregory written in Italy was not produced until Johannes Hymonides (aka John the Deacon) in the 9th century.[citation needed]

Monuments

The namesake church of

In England, Gregory, along with Augustine of Canterbury, is revered as the apostle of the land and the source of the nation's conversion.[88]

Throne

An ancient marble chair, which is believed to be the chair of Pope Gregory the Great, is kept in the church San Gregorio Magno al Celio in Rome.[89][90]

Music

Italian composer Ottorino Respighi composed a piece named St. Gregory the Great (San Gregorio Magno) that features as the fourth and final part of his Church Windows (Vetrate di Chiesa) works, written in 1925.[citation needed]

Feast day

The current

Other churches also honour Gregory the Great:

- The

- The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America remember him with a commemoration on 12 March,[94]

- The

- The Anglican Church of Canada remember him with a Memorial on 3 September.[96][97]

- Gregory the Great is remembered in the Church of England with a Lesser Festival on 3 September.[98]

A traditional procession is held in Żejtun, Malta, in honour of Saint Gregory (San Girgor) on Easter Wednesday, which most often falls in April, the range of possible dates being 25 March to 28 April.[citation needed] The feast day of Saint Gregory also serves as a commemorative day for the former pupils of Downside School, called Old Gregorians. Traditionally, OG ties are worn by all of the society's members on this day.[citation needed]

Written works

- Gregory (n.d.). "Cod. Sang. 211". Homiliae in Ezechielem I-XXII. St. Gallen, Abbey Library. .

Modern editions

- Homiliae in Hiezechihelem prophetam, ed. Marcus Adriaen, CCSL 142 (Turnhout: Brepols, 1971)

- Dialogorum libri quattuor seu De miraculis patrum italicorum: Grégoire le Grand, Dialogues, ed. Adalbert de Vogüé, 3 vols., Sources crétiennes 251, 260, 265 (Paris, 1978–1980) – also available via the Brepols Library of Latin Texts online database at Library of Latin Texts – online (LLT-O)

- Moralia in Iob, ed. Marcus Adriaen, 3 vols. CCSL 143, 143A, 143B (Turnhout: Brepols, 1979-1985)

Translations

- The Dialogues of Saint Gregory the Great, trans. Edmund G. Gardner (London & Boston, 1911).

- Pastoral Care, trans. Henry Davis, ACW 11 (Newman Press, 1950).

- The Book of Pastoral Rule, trans. with intro and notes by George E. Demacopoulos (Crestwood, New York: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, 2007).

- Reading the Gospels with Gregory the Great: Homilies on the Gospels, 21–26, trans. Santha Bhattacharji (Petersham, Massachusetts, 2001) (translations of the 6 Homilies covering Easter Day to the Sunday after Easter).

- The Letters of Gregory the Great, trans. with intro and notes by John R. C. Martyn (Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 2004). (3 volume translation of the Registrum epistularum.)

- Gregory the Great: On the Song of Songs, CS244 (Collegeville, Minnesota, 2012).

See also

- Category:Documents of Pope Gregory I

- Libellus responsionum

- List of Catholic saints

- List of popes

- Pope Saint Gregory I, patron saint archive

- The Holy Sinner, a German novel written by Thomas Mann

References

Notes

- ^ Gregory had come to be known as 'the Great' by the late ninth century, a title which is still applied to him. See Moorhead 2005, p. 1

- ^ Gregory mentions in Dialogue 3.2 that he was alive when Totila attempted to murder Carbonius, Bishop of Populonia, probably in 546. In a letter of 598 (Register, Book 9, Letter 1) he rebukes Bishop Januarius of Cagliari, Sardinia, excusing himself for not observing 1 Timothy 5.1, which cautions against rebuking elders. Timothy 5.9 defines elderly women to be 60 and over, which would probably apply to all. Gregory appears not to consider himself an elder, limiting his birth to no earlier than 539, but 540 is the typical selection. See Dudden 1905, pp. 3, notes 1–3 The presumption of 540 has continued in modern times – see for example Richards 1980

- ^ The translator goes on to state that "Paulus Diaconus, who first writ the life of St. Gregory, and is followed by all the after Writers on that subject, observes that ex Greco eloquio in nostra lingua ... invigilator, seu vigilant sonnet." However, Paul the deacon is too late for the first vita, or life.

- ^ The name is biblical, derived from New Testament contexts: grēgorein is a present, continuous aspect, meaning to be watchful of forsaking Christ. It is derived from a more ancient perfect, egrēgora, "roused from sleep", of egeirein, "to awaken someone." see Thayer 1962

- ^ Whether III or IV depends on whether Antipope Felix II is to be considered pope.

- ^ "Palpate et videte, quia spiritus carnem et ossa non-habet, sicut me videtis habere, or "touch me, and look; a spirit has not flesh and bones, as you see that I have." - Luke 24:39

- ^ The dictionary account is apparently based on Bede, Book II, Chapter 1, who used the expression "...impalpable, of finer texture than wind and air."

- ^ Later these deacons became cardinals and from the oratories attached to the buildings grew churches

- ^ "Hanc vero quam Lucas peccatricem mulierem, Ioannes Mariam nominat, illam esse Mariam credimus de qua Marcus septem daemonia eiecta fuisse testatur" (Patrologia Latina 76:1239)

- ^ For the various literary accounts, see Anonymous Monk of Whitby 1985, p. 157, n. 110

- St. Gallen). The earlier story is not necessarily the more accurate, as Gregory is known to have instructed presbyter Candidus in Gaul by letter to buy young English slaves for placement in monasteries. These were intended for missionary work in England: See Ambrosini & Willis 1996, p. 71

- Pelagius II.

Citations

- ^ a b c d Huddleston 1909.

- ^ Flechner 2015, p. 47.

- ^ Ekonomou, 2007, p. 22.

- ^ a b c "St. Gregory Dialogus, the Pope of Rome". oca.org, Orthodox Church in America. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ Ellard 1948, p. 125.

- ^ Livingstone 1997, p. 415.

- ^ Cross & Livingstone 2005, p. 710.

- ^ Calvin 1845, p. 125, Bk IV, Ch. 7.

- ^ Little 1963, pp. 145–157.

- ^ "St. Gregory the Great". Web site of Saint Charles Borromeo Catholic Church. Retrieved 14 November 2009.

- ^ Ælfric 1709, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d Thornton, pp 163–8

- ^ Dudden (1905), page 4.

- ^ Richards 1980.

- ^ Dudden (1905), pages 11–15.

- ^ Dudden (1905), pages 106–107.

- ^ Richards 1980, p. 25.

- ^ Dudden (1905), pages 7–8.

- ^ Markus 1997, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Dudden (1905), pages 36–37.

- ^ a b c Richards 1980, p. 26.

- ^ Richards 1980, p. 44.

- ^ Leyser pg 132

- ^ Cavadini pg 155

- ^ Straw pg 47

- ^ Markus 1997, p. 69.

- ^ Markus 1997, p. 3.

- ^ Ekonomou, 2007, p. 8.

- ^ a b c Ekonomou, 2007, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e Ekonomou, 2007, p. 10.

- ^ Ekonomou, 2007, pp. 10–11.

- ^ a b Ekonomou, 2007, p. 11.

- ^ a b Ekonomou, 2007, p. 12.

- ^ a b c Ekonomou, 2007, p. 13.

- ^ Smith & Wace 1880, p. 415.

- ^ Luke 24:39

- ^ Straw p. 25

- ^ Cavadini p. 39

- ^ Dudden p. 124

- ^ Dudden p. 99

- ^ a b Richards 1980, p. 228.

- ^ Squatriti 2002, p. 54.

- ^ Meehan 1912.

- ^ Dudden (1905) page 316.

- ^ Smith & Cheetham 1875, p. 549.

- ^ Mann 1914, p. 322.

- ^ Ambrosini & Willis 1996, pp. 66–67.

- ^ a b Dudden (1905) pp. 248–249.

- ^ Deanesly 1969, p. 22–24.

- ^ Eden 2004, p. 487.

- ^ Chupungco 1997, p. 17.

- ^ Levy 1998, p. 7.

- ^ Murray 1963, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Straw pg 4

- ^ a b Markus 1997, p. 15.

- ^ Gardner 1911.

- ^ "A Papyrus Puzzle and Some Purple Parchment". British Museum. 12 February 2014. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- ^ Ambrosini & Willis 1996, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Markus 1997, p. i.

- ^ Markus 1997, p. 2.

- ^ Cantor (1993) page 157.

- ^ John 12:1–8

- ^ Luke 7:36–50; Matthew 26:6–13; Mark 14:3–9

- ^ Luke 7:37

- ^ John 12:3

- ^ Mark 16:9

- ISBN 978-1-5064-1188-0.

- ^ Maisch 1998, p. 156, Ch.10.

- ^ Gietmann 1911.

- ^ Bamberg State Library, Msc.Bibl.84

- ^ Rubin 1991, p. 308.

- ^ Zuckermann 2003, p. 117.

- ^ Bede 1999, Book II Ch. I.

- ^ a b Hunt & Poole 1905, p. 115.

- ^ Dudden pg 317

- ^ Gregory n.d., Cod. Sang. 211.

- ^ Letter of Pope Gregory I to John the Faster.

- ^ Bede 1999, Book I section 27 part II.

- ^ Gregory the Great. The Letters of Gregory the Great. Trans. John R. C. Martyn. 3 vols. (2004). Book VI, Epistle XII.

- ^ Richards 1980, p. 232.

- ^ Pope Gregory I, Moralia, sive Expositio in Job, published by Nicolaus Kessler Basel, 1496.

- ^ Barasch 2013.

- ^ H. Ev. 2.37.9; Dial. 4.58.1

- ^ H. Ev. 2.34.15

- ISBN 978-0-7864-1527-4.

- ^ Champ 2000, p. ix.

- ^ Anonymous Monk of Whitby 1985.

- ^ Richards 1980, p. 260.

- ^ "Anglican and Catholic bishops at Ecumenical Summit prepare to travel to Canterbury". AnglicanNews.org. Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- ^ "Virtually visit the Basilica of Santo Stefano al Celio, tribute to martyrs". Aleteia. 26 March 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- ^ "Sacrosanctum concilium". www.vatican.va.

- ^ Calendarium Romanum (Libreria Editrice Vaticana 1969), pp. 100 and 118

- ^ "Commemorations - Church Year - The Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod". www.lcms.org. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ "Lutheran - Religious calendar 2021 - Calendar.sk". calendar.zoznam.sk. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ISBN 978-1-64065-234-7.

- ^ "The Calendar". 16 October 2013. Archived from the original on 22 October 2019. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- ^ "For All the Saints" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022.

- ^ "The Calendar". The Church of England. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

Sources

- Ælfric (1709). An English-Saxon Homily on the Birth-day of St. Gregory: Anciently Used in the English-Saxon Church, Giving an Account of the Conversion of the English from Paganism to Christianity. Translated by Elstob, Elizabeth. London: W. Bowyer.

- Anonymous Monk of Whitby (1985). Bertram Colgrave (ed.). The Earliest Life of Gregory the Great. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-31384-1.

- Ambrosini, Maria Luisa; Willis, Mary (1996). The Secret Archives of the Vatican. Barnes & Noble. ISBN 9780760701256.

- Barasch, Moshe (2013). Theories of Art: 1. From Plato to Winckelmann. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-135-19979-1.

- Bede (1999). McClure, Judith (ed.). The Ecclesiastical History of the English People: The Greater Chronicle; Bede's Letter to Egbert. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192838667.

- Calvin, John (1845). Institutes of the Christian Religion. Vol. Third. Translated by Henry Beveridge. Edinburgh: Calvin Translation Society.

- ISBN 9780060170332.

- Cavadini, John, ed. (1995). Gregory the Great: A Symposium. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press.

- Champ, Judith F. (2000). The English Pilgrimage to Rome: A Dwelling for the Soul. Gracewing. ISBN 978-0-85244-373-6.

- Chupungco, Anscar J. (1997). Handbook for Liturgical Studies: Introduction to the liturgy. Liturgical Press. ISBN 978-0-8146-6161-1.

- Clark, Francis (1988). "St. Gregory the Great, Theologian of Christian Experience". American Benedictine Review. 39 (3): 261–276.

- ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3.

- Dagens, Claud (1977). Saint Grégoire le Grand: Culture et expérience chrétiennes. Paris: Études augustiniennes. ISBN 978-2851210166.

- Deanesly, Margaret (1969). A History of the Medieval Church, 590-1500. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-03959-8.

- Didron, Adolphe Napoléon (1851). Christian Iconography: Comprising the History of the Nimbus, the Aureole, and the Glory, the History of God the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. Henry G. Bohn. ISBN 9780790580258.

- Demacopoulos, George E. (2015). Gregory the Great: Ascetic, Pastor, and First Man of Rome. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press. ISBN 978-0268026219.

- OCLC 502650100.

- Eden, Bradford L. (2004). "Gregory I, Pope". In Christopher Kleinhenz (ed.). Medieval Italy: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-94880-1.

- Ekonomou, Andrew J. (2007). Byzantine Rome and the Greek Popes: Eastern influences on Rome and the papacy from Gregory the Great to Zacharias, A.D. 590–752. Lexington Books.

- Ellard, Gerald (1948). Christian Life and Worship. Arno. ISBN 978-0-405-10819-8.

- Flechner, Roy (2015). "Pope Gregory and the British: Mission as a Canonical Problem". In Hélène Bouget; Magali Coumert (eds.). En Marge, Histoires des Bretagnes 5. Brest: Université de Bretagne occidentale. pp. 47–65. ISBN 9791092331219.

- Fontaine, Jacques, ed. (1986). Grégoire le Grand: Chantilly, Centre culturel Les Fontaines, 15–19 septembre 1982 : actes (Colloques internationaux du Centre national de la recherche scientifique). Paris: Editions du Centre national de la recherche scientifique. ISBN 978-2222039143.

- Gardner, Edmund G., ed. (1911). The Dialogues of Saint Gregory the Great: Re-edited with an Introduction and Notes. London: P. L. Warner.

- Gietmann, G. (1911). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 11. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Huddleston, Gilbert (1909). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 6. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Hunt, William; Poole, Reginald Lane (1905). The Political History of England ...: The history of England from the accession of Richard II to the death of Richard III, 1377-1485. Longmans, Green & Co.

- Levy, Kenneth (1998). Gregorian Chant and the Carolingians. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01733-6.

- Leyser, Conrad (2000). Authority and Asceticism from Augustine to Gregory the Great. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Little, Lester K. (1963). "Calvin's Appreciation of Gregory the Great". Harvard Theological Review. 56 (2): 145–157. S2CID 164097334.

- Livingstone, Elizabeth A. (1997). Studia Patristica. Peeters. ISBN 978-90-6831-868-5.

- Maisch, Ingrid (1998). Mary Magdalene: The Image of a Woman Through the Centuries. Liturgical Press. ISBN 978-0-8146-2471-5.

- Mann, Horace Kinder (1914). The Lives of the Popes in the Early Middle Ages. Vol. X. K. Paul, Trench, Trübner.

- Markus, R.A. (1997). Gregory the Great and His World. Cambridge: University Press.

- McGinn, Bernard (1996). The Growth of Mysticism: Gregory the Great Through the 12 Century (The Presence of God) (v. 2). New York: Crossroad. ISBN 978-0824516284.

- McGinn Bernard, & McGinn Patricia Ferris (2003). Early Christian Mystics: The Divine Vision of the Spiritual Masters. New York: Crossroad. ISBN 978-0-8245-2106-6.

- Meehan, Andrew B. (1912). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 13. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ISBN 978-0-88-141056-3.

- Moorhead, John (2005). Gregory the Great. The Early Church Fathers (1st ed.). New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0415233903.

- Murray, Gregory (1963). Gregorian Chant According to the Manuscripts. L. J. Cary & Co.

- Ricci, Cristina (2002). Mysterium dispensationis. Tracce di una teologia della storia in Gregorio Magno (in Italian). Rome: Centro Studi S. Anselmo.. Studia Anselmiana, volume 135.

- Richards, Jeffrey (1980). Consul of God. London: Routelege & Keatland Paul.

- Rubin, Miri (1991). Corpus Christi: The Eucharist in Late Medieval Culture. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-43805-6.

- Schreiner, Susan E. (1988). "'Where Shall Wisdom Be Found?': Gregory's Interpretation of Job". American Benedictine Review. 39 (3): 321–342.

- Smith, William; Cheetham, Samuel (1875). A dictionary of Christian antiquities: Comprising the History, Institutions, and Antiquities of the Christian Church, from the Time of the Apostles to the Age of Charlemagne. J. Murray.

- Smith, William; Wace, Henry (1880). A Dictionary of Christian Biography: Literature, Sects and Doctrines. Vol. II Eaba – Hermocrates. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

- Squatriti, Paolo (2002). Water and Society in Early Medieval Italy, AD 400-1000. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52206-9.

- Straw, Carole E. (1988). Gregory the Great: Perfection in Imperfection. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Thayer, Joseph Henry (1962). Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament being Grimm's Wilke's Clavis Novi Testamenti Translated Revised and Enlarged. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan.

- Thornton, Father James (2006). Made Perfect in Faith. Etna, California, US: Center for Traditionalist Orthodox Studies. ISBN 978-0-911165-60-9.

- Weber, Leonhard (1947). Hauptfragen der Moraltheologie Gregors des Grossen: Ein Bild Altchristlicher Lebensführung. Freiburg in der Schweiz: Pauluscruckerei.

- Wilken, Robert Louis (2001). "Interpreting Job Allegorically: The Moralia of Gregory the Great". Pro Ecclesia. 10 (2): 213–226. S2CID 211965328.

- ISBN 978-1-4039-3869-5.

External links

- Works by Pope Gregory I at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- "Documenta Catholica Omnia: Gregorius I Magnus" (in Latin). Cooperatorum Veritatis Societas. 2006. Retrieved 10 August 2008. Index of 70 downloadable .pdf files containing the texts of Gregory I.

- "Complete English translation of Gregory's Moralia in Job". Found on the website: Lectionary Central.

- "Moralia in Iob (book 1–35) (Msc.Bibl.41)" (in Latin). Digitized by the Staatsbibliothek Bamberg.

- "St Gregory Dialogus, the Pope of Rome". synaxarion.

- Noch ein Höhlengleichnis. Zu einem metaphorischen Argument bei Gregor dem Großen by Meinolf Schumacher (in German).

- Women's Biography: Barbara and Antonina, contains two of his letters.

- St. Gregory engraved by Anton Wierix from the De Verda Collection

- Saint Gregory the Great at the Christian Iconography website

- Of St. Gregory the Pope from Caxon's translation of the Golden Legend

- MS 484/21 Dialogorum ... libri quatuor de miraculis at OPenn