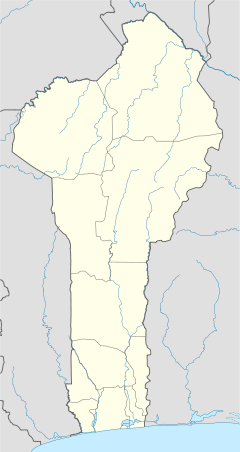

Porto-Novo

Porto-Novo

Xɔ̀gbónù Hogbonu, Àjàṣẹ́ | |

|---|---|

Capital city and commune | |

Skyline, Grande Mosquee Porto-Novo, Porto Novo Cathedral, Pirogues sur lagune de Porto-Novo, Vue d'une entrée de la Grande mosquée, La statue du roi Toffa 1er, Ouando Market, Jardin des plantees et de la nature, Charles de Gaulle stadium | |

| Coordinates: 6°29′50″N 2°36′18″E / 6.49722°N 2.60500°E | |

| Country | |

| Department | Ouémé |

| Established | 16th century |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Emmanuel Zossou |

| Area | |

| • Capital city and commune | 110 km2 (40 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 110 km2 (40 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 38 m (125 ft) |

| Population (2013)[1] | |

| • Capital city and commune | 264,320 |

| • Density | 2,400/km2 (6,200/sq mi) |

| Website | Official website |

Porto-Novo (

Situated on an inlet of the

Etymology

The name Porto-Novo is of Portuguese origin, literally meaning "New Port". It remains untranslated in French, the national language of Benin.

History

Porto-Novo was once a tributary of the

Although historically the original inhabitants of the area were Yoruba speaking, there seems to have been a wave of migration from the region of Allada further west in the 1600s, which brought Te-Agbalin (or Te Agdanlin) and his group to the region of Ajashe in 1688.[6] This new group brought with them their own language, and settled among the original Yoruba. It would appear that each ethnic group has since maintained their ethnic idenitites without one group being linguistically assimilated into the other.[citation needed]

In 1730, the Portuguese Eucaristo de Campos named the city "Porto-Novo" because of its resemblance to the city of Porto.[7][8] It was originally developed as a port for the slave trade.[9]

In 1861, the

The kings of Porto-Novo continued to rule in the city, both officially and unofficially, until the death of the last king, Alohinto Gbeffa, in 1976.[6] From 1908, the king held the title of Chef supérieur.[citation needed]

Many

Under French colonial rule, flight across the new

Seat of government

Benin's parliament (Assemblée nationale) is in Porto-Novo, the official capital, but Cotonou is the seat of government and houses most of the governmental ministries.

Economy

The region around Porto-Novo produces palm oil, cotton and kapok.[11] Petroleum was discovered off the coast of the city in 1968 and has become an important export since the 1990s.[12] Porto-Novo has a cement factory.[citation needed] The city is home to a branch of the Banque Internationale du Bénin, a major bank in Benin, and the Ouando Market.[citation needed]

Transport

Porto-Novo is served by an extension of the

Demographics

Porto-Novo had an enumerated population of 264,320 in 2013.

Population trend:[1]

- 1979: 133,168 (census)

- 1992: 179,138 (census)

- 2002: 223,552 (census)

- 2013: 264,320 (census)

Geography and climate

Porto-Novo has a tropical savanna climate (Köppen Aw) with consistently hot and humid conditions and two wet seasons: a long wet season from March to July and a shorter rain season in September and October. The city’s location on the edge of the Dahomey Gap makes it much drier than would be expected so close to the equator, although it is less dry than Accra or Lomé.

| Climate data for Porto-Novo | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 27 (81) |

28 (82) |

28 (82) |

28 (82) |

27 (81) |

26 (79) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

25 (77) |

26 (79) |

27 (81) |

27 (81) |

26 (79) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 23 (0.9) |

34 (1.3) |

86 (3.4) |

127 (5.0) |

215 (8.5) |

370 (14.6) |

129 (5.1) |

44 (1.7) |

89 (3.5) |

140 (5.5) |

52 (2.0) |

16 (0.6) |

1,325 (52.1) |

| Source: [14] | |||||||||||||

Administrative divisions

Culture

- The

- World Heritage Tentative List on October 31, 1996 in the Cultural category.[15]

- Jardin Place Jean Bayol is a large plaza which contains a statue of the first King of Porto-Novo.

- The Da Silva Museum is a museum of Beninese history.[6] It shows what life was like for the returning Afro-Brazilians.

- The palais de Gouverneur (governor's palace) is the home of the national legislature.

- The Isèbayé Foundation is a museum of Voodoo and Beninese history.[6]

Music

Sports

The Stade Municipal and the Stade Charles de Gaulle are the largest

Places of worship

Among the

Notable people

- Alexis Adandé, archaeologist[18]

- Anicet Adjamossi, footballer.[19]

- Kamarou Fassassi, politician.[20]

- Romuald Hazoume, artist[21]

- Samuel Oshoffa, who founded the Celestial Church of Christ.[22]

- Claudine Talon, first lady of Benin (since 2016)[23]

- Marc Tovalou Quenum, lawyer, writer and pan-Africanist.[24]

- Paulin Soumanou Vieyra, director and author[25]

Notes

- ^ a b c "Benin: Departments, Major Cities & Towns - Population Statistics, Maps, Charts, Weather and Web Information". Archived from the original on 2019-05-09. Retrieved 2019-03-28.

- ^ "Porto-Novo". Atlas Monographique des Communes du Benin. Archived from the original on September 12, 2022. Retrieved January 5, 2010.

- ^ "Communes of Benin". Statoids. Archived from the original on January 2, 2010. Retrieved January 5, 2010.

- ISBN 978-0-982-2619-10. Archivedfrom the original on April 7, 2022. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

- ISBN 978-0-81087-17-17. Archivedfrom the original on April 7, 2022. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Butler, Stuart (2019) Bradt Travel Guide - Benin, pgs. 121-131

- ^ Mathurin C. Houngnikpo, Samuel Decalo, Historical Dictionary of Benin, Rowman & Littlefield, USA, 2013, p. 297

- ^ Britannica, Porto-Novo Archived 2019-06-21 at the Wayback Machine, britannica.com, USA, accessed on July 7, 2019

- ISBN 978-1-4411-5-81-30. Archivedfrom the original on 2022-03-14. Retrieved March 9, 2015.

- ^ Hargreaves, John (1963). Prelude to the Partition of West Africa. London: MacMilland. pp. 59–60.[ISBN missing]

- ISBN 978-0-531-00720-4.

A large agricultural school in Porto Novo prepares its students for their role in manufacturing such goods as soap, exported palm oil, cotton, and kapok.

- ISBN 978-0-8160-7229-3.

- ^ ZEMIJAN - Taxis motos (Bénin, ancien Dahomey), retrieved 2023-02-18

- ^ "Weatherbase". Weatherbase. Archived from the original on March 6, 2020. Retrieved December 13, 2012.

- ^ "La ville de Porto-Novo : quartiers anciens et Palais Royal - UNESCO World Heritage Centre". Archived from the original on 2022-09-12. Retrieved 2019-12-26.

- ^ Chants & danses Adjogan à Porto-Novo (Hogbonou) - Archives (Bénin, ancien Dahomey), retrieved 2023-02-18

- ^ J. Gordon Melton, Martin Baumann, ‘‘Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices’’, ABC-CLIO, USA, 2010, p. 338

- ISBN 978-1-4419-0465-2

- ^ "Fiche de Anicet Adjamossi (Locminé), l'actu le palmares et les stats de Anicet Adjamossi". L'Équipe (in French). Retrieved 2023-02-18.

- ^ "Government page on Fassassi" (in French). Archived from the original on November 19, 2003. Retrieved 2007-05-07.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). - ^ "OCTOBER GALLERY | ROMUALD HAZOUMÈ | ART | BIOGRAPHY | ART FOR SALE". octobergallery.co.uk. Retrieved 2023-02-18.

- ISBN 978-0-299-22910-8. Archivedfrom the original on 2022-02-13. Retrieved 2020-10-19.

- ^ "Discrète mais influente Claudine Gbènagnon Talon". Africa Intelligence. 2018-05-23. Archived from the original on 2020-08-10. Retrieved 2022-05-29.

- ^ Marc Tovalou Quenum profile, (in English)

- ^ "Vieyra, Paulin Soumanou". African Film Festival. April 12, 2018. Retrieved 2023-02-18.

Further reading

- Sappho Charney (1996). "Porto-Novo (Oueme, Benin)". In Noelle Watson (ed.). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Middle East and Africa. UK: Routledge. p. 588+. ISBN 1884964036.