Portraits of Odaenathus

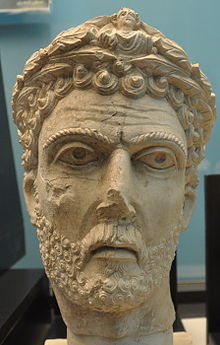

Palmyrene portraits were usually abstract, depicting little individuality. Most reported portraits of Odaenathus are undated and have no inscriptions, making identification speculative. Generally, the criteria for determining whether a piece represents the king are its material (imported marble, in contrast to local limestone) and iconography, such as the presence of royal attributes (crowns or diadems). Several limestone head portraits from Palmyra were identified by several twentieth-century scholars as depicting Odaenathus, based on criteria such as the size of the portrait and the presence of a wreath; the latter element was not special in Palmyrene portraits, as priests were also depicted with wreaths. More recent research on the limestone portraits indicates that these pieces were probably funerary objects depicting private citizens.

Two marble heads, both reflecting a high level of individuality, are more likely to be portraits of the king. The first marble sculpture depicts a man in a royal diadem, and the second shows the king in an eastern royal tiara. Two Palmyrene tesserae, depicting a bearded king wearing a diadem and an earring, are also likely to be depictions of Odaenathus, and two mosaic panels have been identified as possibly depicting him: one of them portrays a rider (probably Odaenathus) killing a Chimera, which fits a prophecy in the thirteenth Sibylline Oracle that includes an account contemporary to Odaenathus, prophesying that he will kill Shapur I, who is described as a beast.

Background

Clearly attributed busts or statues of Odaenathus have not survived,[15] and the king did not mint coins bearing his image.[16] A few small clay tesserae were found in Palmyra with impressions of the king and his name,[17] but no large-scale portrait has been confirmed through inscriptions (limiting knowledge of Odaenathus' appearance).[15] In general, Palmyrene sculptures are rudimentary portraits; although individuality was not abandoned, most pieces exhibit little difference among figures of a similar age and gender.[18]

Limestone sculptures

Several large head sculptures have been suggested by scholars to be depictions of the king:[19]

In Copenhagen and Istanbul

Two head sculptures, one at the

The columns of the Great Colonnade at Palmyra had consoles which held statues of notable Palmyrenes.[26] The Danish rabbi and scholar David Jakob Simonsen proposed that the Copenhagen head was part of a console statue of a Palmyrene who was honoured by the city.[27] The archaeologist Frederik Poulsen considered that the wreath on the Copenhagen head is reminiscent of portraits of the Roman emperor Septimius Severus, and the long face is similar to portraits of Emperor Maximinus Thrax.[28] The archaeologist Valentin Müller, based on the Copenhagen head's moving posture, forehead, and a characteristic fold between the nose and mouth, proposed that it was sculpted during the time of Emperor Decius (reigned 249–251).[note 2][30]

King Odaenathus was the son of Hairan, as attested by many inscriptions.[31] In earlier scholarship, a character designated "Odaenathus I", whose existence was deduced from a sepulchral inscription in Palmyra recording the lineage of the tomb's owner (the supposed Odaenathus I), was considered the father of Hairan and grandfather of King Odaenathus (who was designated Odaenathus II).[32] In a 1976 article, the archaeologist Harald Ingholt proposed a date range of 230–250 for the Copenhagen and Istanbul heads, a decade earlier or later also possible.[33] Ingholt concluded that the heads should be dated to 250, and represented Odaenathus I, without excluding the possibility that they might represent Odaenathus II or his father Hairan.[34] In 1985, the archaeologist Michael Gawlikowski proved that Odaenathus I was identical to King Odaenathus, which is confirmed by an inscription securely attributed to the king, recording his lineage, the same as that mentioned in the earlier known sepulchral inscription.[32] Based on the conclusions of Gawlikowski, the archaeologist Ernest Will assigned the Copenhagen portrait to King Odaenathus.[35]

The archaeologist Klaus Parlasca rejected Ingholt's hypothesis regarding the honorary function of the portraits, and considered the two heads fragments of a funeral kline (sarcophagus lid).[21] The archaeologist Jean-Charles Balty noted the relative incompleteness of the rear of both portraits and the thickness of the necks, indicating that the heads were not intended to be seen in profile. This supports Parlasca's theory that the heads were part of a monumental, frontal kline in the exedra (semicircular recess) of a tomb; an example of such composition is the hypogeum (underground tomb) of the Palmyrene noble Shalamallat, which has a similar sculpture on the lid of a sarcophagus.[36] The historian Udo Hartmann considered Ingholt's arguments unconvincing, and his identification arbitrary.[37] The archaeologist Eugenia Equini Schneider agreed with Simonsen and Ingholt that the heads had an honorary function,[21] but (based on their iconography) dated them to the late second or early third century.[38]

From the hexagonal tomb

Three head sculptures were excavated in 1994 from a hexagonal tomb in Palmyra's northern necropolis by its head of antiquities, Khaled al-As'ad,[39][40] and moved to the city's museum. According to Balty, the heads are full replicas, intended to represent the same person; their similarities are not the result of a workshop's standards.[41] They resemble the heads in the Copenhagen and Istanbul museums, chiefly differing in hairstyle.[40]

One of the hexagonal tomb portraits, code B2726/9163, is 45 centimetres (18 in) tall and was identified as a portrait of the king by the archaeologist Michel Fortin.[note 3][43] Balty disagreed with Fortin's identification, stating that their discovery in a tomb and their material (limestone) support identification as funerary portraits.[41] Gawlikowski suggested that the heads depicted three men from the same family, and considered that their excavation from a tomb, and their remarkable resemblance to the portraits in Copenhagen and Istanbul, confirm that the latter two were also funerary, and not honorary, objects.[40]

In Damascus museum

The sculpted head (code C1519) can be compared with dated Palmyrene funerary portraits and contemporary Roman portraiture and suggests a mid-third-century crafting date.[note 4][45] It is 33 centimetres (13 in) tall, and the nose and most of the mouth are abraded. The sculpture represents an older man, with deep wrinkles on the forehead. The face is impersonal; the engraved eyes look straight at the viewer but are motionless, distant, and devoid of expression. The head is crowned by a laurel wreath with a cabochon gem in its centre.[46] The sculpture has a minimum of individuality: the modelling of the face lacks articulation, the eyes are expressionless, and the facial hair is rigid and stylized.[47] The portrait is influenced by a standard artistic model. The massive square skull is similar to the model used for Emperor Gallienus' portraits, so Gallienus' model may have been modified to incorporate features typical of Palmyrene portraiture.[note 5][47] The piece was tentatively identified as depicting the king by the archaeologist Johannes Kollwitz,[49] but Parlasca considered it a fragment of a funeral kline.[50]

Benaki Museum

| External image | |

|---|---|

A limestone head sculpture, 30 centimetres (12 in) tall, is at the Benaki Museum in Athens under inventory number 36361. The head was acquired commercially in 1989, and no information about its exact excavation location in Syria is known; it was moved to the museum a decade later.[51] The limestone material and many similarities to the portraits in Copenhagen and Istanbul make Palmyra the most likely place of origin.[52]

The face is severely damaged, and many parts of the wreath and nose are broken. The portrait is characterized by the proportions and elongated construction of the head. Its laurel wreath is incomplete, stopping just behind the ears. A miniature bust whose head is damaged is in the centre of the wreath, above the forehead. The eyes are large, and framed by sharp eyelids.[51] The facial features of the man depicted indicate advanced age, and his expression is reminiscent of portraits depicting Roman emperors, philosophers and priests.[53] The back of the portrait is unfinished and the neck is massive and thick.[54] Due to the resemblance of the Benaki head to the portraits at the Copenhagen and Istanbul museums, the archaeologist Stavros Vlizos proposed that the man belonged to the family of Odaenathus.[55]

Limestone portraits: conclusion

According to Gawlikowski, the wreaths appearing on the limestone portraits such as those in the Copenhagen and Istanbul museums do not necessarily indicate Roman corona civica honours; much headgear worn by Palmyrene priests had wreaths without Roman connotations. Many funerary portraits used as headstones in Palmyrene tombs depicted the deceased with wreaths whose meaning, in a Palmyrene context, is unclear.[19]

Gawlikowski, agreeing with Parlasca, maintained that most of the oversized limestone heads with thick necks were connected to funeral practices such as sarcophagus lids;[19] this includes the portraits from the hexagonal tomb and the Copenhagen and Istanbul museums.[40] As for Simonsen's suggestion that the Copenhagen portrait belonged to an honorary statue set on a bracket (console) atop a column in the city's streets,[27] Palmyrene honorary statues that stood on the columns consoles were made of bronze, and it is doubtful that the brackets could support the weight of stone statues;[40] such honorary portraits in Palmyra stood on bases on the ground.[40] According to Gawlikowski, there is no reason to believe that the portraits are of the same person, despite their similarities;[19] the limestone portraits were not depictions of the king or his family, and they appear to be funerary in function.[40]

Marble portraits

Marble was a symbol of political and social prestige, and had to be imported to Palmyra;[note 6][56] most of Palmyra's sculptures were made of limestone, and the use of marble is noteworthy.[40]

Tiara portrait

| External image | |

|---|---|

This portrait was found in 1940 in the vicinity of the Palmyrene agora at the same time that five headless marble statues, depicting two men and three women, were found in a building considered to be the senate (also near the agora); it is uncertain if the tiara portrait was found in the same building. Although the portrait is lost and was never published, photographs of it survive in the archives of l'Institut Français d'Archéologie du Proche-Orient (IFAPO).[40] The face is oval and a long, drooping, curved moustache joins the beard. The lower part of the face is broken, only the first row of beard curls surviving. The nose is also broken; the eyes are wide open and the lower eyelids are a little heavy,[57] giving intensity to the expression.[58] Two vertical folds at the beginning of the nose accentuate the eyes, which are topped with strong eyebrows. The forehead is high, with two horizontal furrows. The headdress, apparently a turban, is damaged at the back and on the right temple. In the middle of the turban's top, a circular hole apparently housed a dowel which held another headdress piece that would have been framed by the turban's elevated rim.[57]

The portrait's craftsmanship is remarkable, according to Balty, and reflects a nobility of expression.

Diadem portrait

A 27-centimetre-tall (11 in) marble head portrait, in the Palmyra Museum (Inv. B 459/1662),[62] apparently was part of a life-sized statue.[63] The piece is poorly preserved and fragmentary. The hair begins on the centre top of the head with long sparse strands, which are carved flat and held by a diadem. The beard binds to the hair at the temples and is placed low on the cheeks with a stiff, clean cut. The forehead is furrowed by deep lines beginning at the top of the nose.[64] The man is depicted in traditional Greek style except for his hair, which resembles Iranian Parthian examples rather than the hairstyle seen on Roman portraits.[62] Balty considered it likely that the portrait depicts Odaenathus, noting the similarities to the tiara portrait: the eyes are also wide open, and the gaze has the same intensity. The most noticeable difference is the simpler hairstyle of the diadem portrait; Balty suggested that if the hairstyle difference makes it necessary to ascribe the diadem portrait to a different man than the tiara portrait, Odaenathus' viceroy Septimius Worod is a suitable candidate since the tiara (a symbol of royalty) is missing.[65]

While lacking the tiara,[65] the portrait depicts its subject wearing a diadem, the main item in the regalia of Hellenistic monarchs;[66] it was used to connect rulers to Alexander the Great, a source of legitimacy for Hellenistic kings. The diadem was probably linked in a Greek context to the god Dionysus, who played a part in royal ideology as a victorious leader,[67] and the headdress became a symbol of monarchy in the East.[68] The Hellenistic Seleucid kings of Syria used a white cloth diadem, and their legacy was a source of legitimacy in the East for early Parthian monarchs against Roman claims (leading to the adoption of their symbols by the Parthian court).[69] The diadem depicted in the portrait is Oriental in style, reminiscent of Parthian iconography.[64] Odaenathus' successor and son, Vaballathus, was depicted wearing a diadem on his coins; this indicated his royal rank to his eastern subjects,[70] and Herodianus was also crowned with a diadem and tiara by his father in 263.[9] Gawlikowski considered it likely that the portrait depicts Odaenathus, and that the lack of a tiara (which made Balty hesitant in his identification of the portrait's subject as Odaenathus) is offset by the royal diadem.[61]

Tesserae portraits

Palmyrene tesserae are small tokens with a variety of designs, which were probably used as invitation tickets to ritual temple banquets. About 1,000 designs were known in 2019; most are terracotta, but a few are lead, iron, or bronze.[71] The major reference for Palmyrene tesserae is the Recueil des Tessères de Palmyre (RTP).[72][73] Some depict Odaenathus:

Tessera RTP 4

This tessera is in the National Museum of Damascus. On one side, a man's head is shown; covering all the available surface, he has a heavily built face, a full beard, and thick hair or a headdress (probably the lion-skin dress of Heracles). The other side of the tessera has the profile of a mature bearded man wearing a royal diadem and a triangular earring.[17] Tesserae are made by pressing a gem into clay; such seals, portraying royals without inscription, can be issued only in the name of the person depicted. Gawlikowski proposed that the king is Odaenathus. If Heracles is depicted, this was meant to glorify the monarch's victory over Persia; the tessera could have been a ticket to the coronation of Odaenathus and his son, Herodianus.[74]

Tessera RTP 5

This tessera, also in the National Museum of Damascus, depicts a king in a tiara on one side; a ball of hair in chignon style is attached to the back of the head. The king's iconography is similar in style to the portrait of Herodianus on the lead token.[17] The authors of the RTP postulated the presence of a beard, and considered it possible that the king is Odaenathus.[73] Gawlikowski disagreed, as the face depicted is youthful and cannot be a representation of the middle aged Odaenathus. Gawlikowski also disputed the presence of a beard. Although the other side of the tessera is severely damaged, traces of a triangular earring similar to that depicted in tessera RTP 4 can be seen. Gawlikowski concluded that Herodianus is depicted with a tiara and Odaenathus, in the same bearded portrait as RTP 4 with the diadem and earring, must have appeared on the worn-out side.[17]

Tessera RTP 736

With seven known pieces, this series in the National Museum of Damascus depicts two men reclining on a couch in priestly attire on each side. On one side, the name of Odaenathus' eldest son Hairan (I) is inscribed under the couch.[75] Several scholars, including Udo Hartmann, maintain that Hairan I is Herodianus, and the latter is the Greek version of the local name.[76] The historian David S. Potter argued that the Hairan on tessera RTP 736 is Hairan II (a younger son of Odaenathus, whom Potter identified with Herodianus).[77] On the other side of the tessera, the name of Vaballathus is inscribed; on both sides, the name of Odaenathus is inscribed to the left of the men. The tesserae depict the king on both sides, his eldest son on one side and his eventual successor on the other. Since no royal attributes are shown, the tesserae might date to the late 250s.[75]

Mosaic

In 2003, a 9.6-by-6.3-metre (31 by 21 ft) mosaic floor was discovered in Palmyra;[78] based on the border style, it dates to the second half of the third century. The mosaic floor is a carpet of geometric and symmetrical composition, surrounding a rectangular panel in the centre which is divided into two panels of equal dimensions;[79] Gawlikowski named them La chasse au tigre (The Tiger Hunt) and Le tableau de Bellérophon (The panel of Bellerophon).[80]

The Tiger Hunt

The panel depicts a galloping rider attacking a rearing tiger, with a smaller tiger (apparently a female) under the horse's hooves. According to Gianluca Serra (a conservation zoologist based in Palmyra at the time of the panel's discovery), both are Caspian tigers, which were once common in the region of Hyrcania in Iran. The composition strongly resembles some Sassanid silver plates,[81] and the rider is wearing Palmyrene military attire.[82]

Above the horse's head is a three-line inscription.[note 7] The text is Palmyrene cursive and probably the signature of the artist, but the many errors in writing and its incongruous position raise the possibility that it is a secondary addition which attempted to replace an original inscription. The last two letters of the inscription (MR, much larger and more professionally executed than the rest) do not make sense in their current context.[83] Gawlikowski reconstructed them as the word MRN (our lord), a title held in Palmyra by Odaenathus and Herodianus,[84] and interpreted the tiger-hunt scene as a metaphor for Odaenathus' victory over Shapur I; the Hyrcanian tigers may represent the Persians, and the rider may represent Odaenathus.[85]

The Panel of Bellerophon

The thirteenth Sibylline Oracle, a collection of prophecies probably compiled by Syrian authors to glorify Syrian rulers, includes a prophecy added to the initial text during the reign of Odaenathus:[87] "Then shall come one who was sent by the sun [Odaenathus], a mighty and fearful lion, breathing much flame. Then he with much shameless daring will destroy ... the greatest beast – venomous, fearful and emitting a great deal of hisses [Shapur I]".[88] Gawlikowski proposed that Odaenathus is depicted as Bellerophon, and the Chimera (who fits the description of Shapur I as a great beast in the thirteenth Sibylline Oracle) is a representation of the Persians.[89]

Painting of Dura-Europos

A wall painting from the temple of Artemis Azzanathkona in Dura-Europos depicts a Roman soldier offering a sacrifice to a deity with a Palmyrene mounted figure to the far left. Michael Rostovtzeff argued that it depicts the celebration of Odaenathus' victory over Shapur I and his recovery of the city; the Roman soldier is making the offering in the presence of the victorious king.[90] The Palmyrene figure's upper body is heavily eroded and the painting is undated and there is no inscription mentioning Odaenathus. Thus, the identification is considered tentative by several scholars such as Hopkins and James.[91][92]

Notes

- ^ Since the 1895 Istanbul museum catalogue does not include the piece, it was acquired after that date.[20]

- ^ The archaeologist Harald Ingholt rejected Müller's suggestion that the "characteristic fold" between the nostrils and mouth appeared during Decius' reign, noting that it had appeared on busts of the Palmyrene noble Atenatan in 133–134.[29]

- ^ Another portrait is coded B2727/9127.[41][42] An image of it can be viewed on the Getty Images website, listed in the external links

- ^ The catalogue of the Department of Greco-Roman Antiquities at the Damascus Museum, compiled by the museum's Selim Abdul-Hak in 1951, contains an illustration (numbered 13) of the sculpture.[44]

- ^ A jewelled-wreath portrait in the museum at Palmyra (Inv. B 2186-CD 134,62) is 26 centimetres (10 in) tall, and is close in iconography and style to the Damascus sculpture. According to Equini Schneider, it could be attributed to the same workshop, and the same Gallienic model was used in its production.[47] The wreath indicates an exalted social position, and the sculpture has been dated to early in the second half of the third century. It was discovered on May 10, 1962 in the foundations of Palmyra's western gate.[48] Although the design of the hair and beard is similar to the Damascus portrait, the features of the Palmyra portrait are more personal; the face is more elongated, and its expression is severe and frowning.[47]

- ^ The historian Hazel Dodge, drawing on exclusively macroscopic observations, found material indicating the presence of local marble; this turned out to be travertine extracted from the al-Sukkari and Bazurieh regions, 22 km (14 mi) south of Palmyra.[56]

- ^ "dydṭs ' bd // psps d'hw // wbnwhy MR" – Translation: Diodotos made this floor, him and his sons MR.[81]

References

Citations

- ^ Southern 2008, p. 44.

- ^ Ball 2002, p. 77.

- ^ Southern 2008, p. 43.

- ^ Dignas & Winter 2007, p. 159.

- ^ Bryce 2014, p. 291.

- ^ Hartmann 2001, p. 172.

- ^ de Blois 1976, p. 3.

- ^ Hartmann 2001, pp. 149, 176, 178.

- ^ a b c Andrade 2013, p. 333.

- ^ Young 2003, pp. 214, 215.

- ^ Hartmann 2001, p. 180.

- ^ Dodgeon & Lieu 2002, p. 71.

- ^ Southern 2008, p. 78.

- ^ Bryce 2014, p. 299.

- ^ a b Wadeson 2014, pp. 49, 54.

- ^ Young 2003, p. 215.

- ^ a b c d Gawlikowski 2016, p. 131.

- ^ Strong 1995, p. 168.

- ^ a b c d Gawlikowski 2016, p. 126.

- ^ Ingholt 1976, p. 116.

- ^ a b c d e Equini Schneider 1992, p. 126.

- ^ Colledge 1976, p. 91.

- ^ Ingholt 1976, pp. 115, 116.

- ^ a b Ingholt 1976, p. 115.

- ^ Equini Schneider 1992, p. 127.

- ^ Stoneman 1994, p. 76.

- ^ a b Simonsen 1889, p. 54.

- ^ Poulsen 1921, p. 86.

- ^ Ingholt 1928, p. 118.

- ^ Müller 1927, p. 24.

- ^ Gawlikowski 1985, p. 253.

- ^ a b Sartre 2005, p. 512.

- ^ Ingholt 1976, p. 119.

- ^ Ingholt 1976, p. 136.

- ^ Balty 2002, pp. 731.

- ^ Balty 2002, pp. 731, 732.

- ^ Hartmann 2001, p. 87.

- ^ Equini Schneider 1992, p. 128.

- ^ al-As'ad 2002, p. 160.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Gawlikowski 2016, p. 127.

- ^ a b c Balty 2002, p. 732.

- ^ Charles-Gaffiot, Lavagne & Hofman 2001, p. 311.

- ^ Fortin 1999, p. 114.

- ^ Abdul-Hak & Abdul-Hak 1951, p. 73.

- ^ Equini Schneider 1992, pp. 130, 131.

- ^ Equini Schneider 1992, p. 131.

- ^ a b c d Equini Schneider 1992, p. 132.

- ^ Michałowski et al. 1964, p. 80.

- ^ Kollwitz 1951, p. 201.

- ^ Parlasca 1989, p. 206.

- ^ a b Vlizos 2001, p. 190.

- ^ Vlizos 2001, p. 195.

- ^ Vlizos 2001, p. 192.

- ^ Vlizos 2001, p. 191.

- ^ Vlizos 2001, p. 206.

- ^ a b Wielgosz 2010, p. 75.

- ^ a b c d Balty 2005, p. 330.

- ^ a b c Balty 2005, p. 333.

- ^ Teixidor 2005, p. 198.

- ^ Balty 2002, p. 741.

- ^ a b Gawlikowski 2016, p. 128.

- ^ a b Parlasca 1985, p. 347.

- ^ Equini Schneider 1992, p. 140.

- ^ a b Equini Schneider 1992, p. 141.

- ^ a b Balty 2002, p. 738.

- ^ Carson 1957, p. 50.

- ^ Papantoniou 2012, p. 307.

- ^ Bardill 2012, p. 18.

- ^ Butcher 2003, p. 35.

- ^ Hartmann 2001, pp. 253, 254.

- ^ Fowlkes-Childs & Seymour 2019, p. 161.

- ^ al-As'ad, Briquel-Chatonnet & Yon 2005, p. 1.

- ^ a b Ingholt et al. 1955, p. 1.

- ^ Gawlikowski 2016, p. 132.

- ^ a b Gawlikowski 2016, pp. 132, 133.

- ^ Southern 2008, p. 9.

- ^ Potter 2014, p. 85.

- ^ Gawlikowski 2005, p. 1293.

- ^ Gawlikowski 2005, p. 1296.

- ^ Gawlikowski 2005, pp. 1298, 1299.

- ^ a b c Gawlikowski 2005, p. 1300.

- ^ Andrade 2018, p. 139.

- ^ Gawlikowski 2005, pp. 1300, 1301.

- ^ Gawlikowski 2005, p. 1301.

- ^ Gawlikowski 2005, p. 1302.

- ^ Gawlikowski 2005, p. 1297.

- ^ Butcher 1996, p. 525.

- ^ Kaizer 2009, p. 185.

- ^ Gawlikowski 2005, p. 1303.

- ^ Rostovtzeff 1943, p. 59.

- ^ Hopkins 1981, p. 155.

- ^ James 1985, p. 116.

Sources

- Abdul-Hak, Selim; Abdul-Hak, Andrée (1951). Catalogue Illustré du Département des Antiquités Greco-Romaines au Musée de Damas (in French). Vol. 1. Damas: Direction Générale des Antiquités et des Museés. OCLC 889099666.

- al-As'ad, Khaled (2002). "Palmira: Ottant'Anni di Scoperte". In Gabucci, Ada (ed.). Zenobia: Il Sogno di Una Regina d'Oriente (in Italian). Electa. pp. 159–63. ISBN 978-8-843-59843-4.

- al-As'ad, Khaled; Briquel-Chatonnet, Françoise; Yon, Jean-Baptiste (2005). "The Sacred Banquets at Palmyra and the Function of the Tesserae: Reflections on the Tokens Found in the Arṣu Temple". In Cussini, Eleonora (ed.). A Journey to Palmyra: Collected Essays to Remember Delbert R. Hillers. Brill. pp. 1–10. ISBN 978-90-04-12418-9.

- Andrade, Nathanael J. (2013). Syrian Identity in the Greco-Roman World. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-01205-9.

- Andrade, Nathanael J. (2018). Zenobia: Shooting Star of Palmyra. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-190-63881-8.

- Ball, Warwick (2002) [1999]. Rome in the East: The Transformation of an Empire. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-82387-1.

- Balty, Jean-Charles (2002). "Odeinat. "Roi des Rois"". Comptes Rendus des Séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres (in French). 146 (2). Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres: 729–741. ISSN 0065-0536.

- Balty, Jean Charles (2005). "La Sculpture". In Delplace, Christiane; Dentzer-Feydey, Jacqueline (eds.). L'Agora de Palmyre. Bibliothèque Archéologique et Historique (in French). Vol. 175. Institut Français du Proche-Orient. pp. 321–41. ISBN 978-2-351-59000-3.

- Bardill, Jonathan (2012). Constantine, Divine Emperor of the Christian Golden Age. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-76423-0.

- Bryce, Trevor (2014). Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-100292-2.

- Butcher, Kevin (1996). "Imagined Emperors: Personalities and Failure in the Third Century. D. S. Potter, Prophecy and History in the Crisis of the Roman Empire: A Historical Commentary on the Thirteenth Sibylline Oracle (Oxford 1990). pp. 443 + xix, 2 maps, 27 Half-Tone Illustrations. ISBN 0-19-814483-0". Journal of Roman Archaeology. 9. University of Michigan Press: 515–27. S2CID 250346143.

- Butcher, Kevin (2003). Roman Syria and the Near East. Getty Publications. ISBN 978-0-89236-715-3.

- Carson, Robert Andrew Glendinning (1957). "Caesar and the Monarchy". Greece & Rome. 4 (1). Cambridge University Press on behalf of The Classical Association: 46–53. S2CID 154997082.

- Charles-Gaffiot, Jacques; Lavagne, Henri; Hofman, Jean-Marc, eds. (2001). "Œuvres Exposées". Moi, Zénobie Reine de Palmyre (Exposition: Mairie du Ve Arrondissement de Paris, 18 Septembre au 16 Décembre 2001). Archeologia, Arte Primitiva e Orientale (in French). Skira. pp. 181–369. ISBN 978-8-884-91116-2.

- Colledge, Malcolm A. R. (1976). The Art of Palmyra. Studies in Ancient Art and Archaeology. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-69003-1.

- de Blois, Lukas (1976). The Policy of the Emperor Gallienus. Dutch Archaeological and Historical Society: Studies of the Dutch Archaeological and Historical Society. Vol. 7. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-04508-8.

- Dignas, Beate; Winter, Engelbert (2007) [2001]. Rome and Persia in Late Antiquity: Neighbours and Rivals. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-84925-8.

- Dodgeon, Michael H; Lieu, Samuel N. C (2002). The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars AD 226–363: A Documentary History. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-96113-9.

- Equini Schneider, Eugenia (1992). "Scultura e Ritrattistica Onorarie a Palmira; Qualche Ipotesi". Archeologia Classica (in Italian). 44. L'Erma di Bretschneider. ISSN 0391-8165.

- Fortin, Michel (1999). Syria, Land of Civilizations. Translated by Macaulay, Jane. Musée de la Civilisation, Québec. ISBN 978-2-761-91521-2.

- Fowlkes-Childs, Blair; Seymour, Michael (2019). The World Between Empires: Art and Identity in the Ancient Middle East. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-1-588-39683-9.

- Gawlikowski, Michal (1985). "Les princes de Palmyre". Syria. Archéologie, Art et Histoire (in French). 62 (3/4). l'Institut Français du Proche-Orient: 251–261. ISSN 0039-7946.

- Gawlikowski, Michal (2005). "L'apothéose d'Odeinat sur une Mosaïque Récemment Découverte à Palmyre". Comptes Rendus des Séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres (in French). 149 (4). Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres: 1293–1304. ISSN 0065-0536.

- Gawlikowski, Michael (2016). "The Portraits of the Palmyrene Royalty". In Kropp, Andreas; Raja, Rubina (eds.). The World of Palmyra. Scientia Danica. Series H, Humanistica, 4. Vol. 6. The Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters (Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab). Printed by Specialtrykkeriet Viborg a-s. ISSN 1904-5506.

- Hartmann, Udo (2001). Das Palmyrenische Teilreich (in German). Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 978-3-515-07800-9.

- Hopkins, Clark (1981) [1979]. The Discovery of Dura-Europos. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-30002-288-9.

- Ingholt, Harald (1928). Studier over Palmyrensk Skulptur (in Danish). C. A. Reitzels Forlag. OCLC 4125419.

- Ingholt, Harald; Seyrig, Henri; Starcky, Jean; Caquot, André (1955). Recueil des Tessères de Palmyre. Bibliothèque Archéologique et Historique. Vol. 58. Imprimerie Nationale. Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner. OCLC 603577481.

- Ingholt, Harald (1976). "Varia Tadmorea". In Frézouls, Edmond (ed.). Palmyre: Bilan et Perspectives. Colloque de Strasbourg 18–20 Octobre 1973, à la Mémoire de Daniel Schlumberger et de Henri Seyrig. Travaux du Centre de Recherche sur le Proche-Orient et la Grèce Antiques. Vol. 3. Association Pour l'étude de la Civilisation Romaine. Universite des Sciences Humaines de Strasbourg. pp. 101–137. OCLC 11574470.

- James, Simon (1985). "Dura-Europos and the Chronology of Syria in the 250s AD". Chiron: Mitteilungen der Kommission für Alte Geschichte und Epigraphik des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts. 15. Beck. ISSN 0069-3715.

- Kaizer, Ted (2009). "The Parthian and Early Sasanian Empires, c. 247 BC – AD 300". In Harrison, Thomas (ed.). The Great Empires of the Ancient World. J. Paul Getty Museum. pp. 174–95. ISBN 978-0-89236-987-4.

- Kollwitz, Johannes (1951). "Zwei Spätantike Porträts im Museum von Damaskus". Annales Archéologiques Arabes Syriennes (in German). 1. Direction Générale des Antiquités et des Museés. ISSN 0570-1554.

- Michałowski, Kazimierz; Strelcyn, Stefan; Filarska, Barbara; Krzyżanowska, Aleksandra; Ostrasz, Antoni; Michałowska, Krystyna; Cukrowska, Zofia (1964). Fouilles Polonaises 1962. Palmyre (in French). Vol. IV. PWN (Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe) – Éditions Scientifiques de Pologne. OCLC 833588867.

- Müller, Valentin Kurt (1927). Zwei Syrische Bildnisse Römischer Zeit. Winckelmannsprogramm der Archäologischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin (in German). Vol. 86. Walter de Gruyter. OCLC 185152569.

- Papantoniou, Giorgos (2012). Religion and Social Transformations in Cyprus: From the Cypriot Basileis to the Hellenistic Strategos. Mnemosyne, Supplements, History and Archaeology of Classical Antiquity. Vol. 347. Brill. ISBN 978-9-004-22435-3.

- Parlasca, Klaus (1985). "Das Verhältnis der Palmyrenischen Grabplastik zur Römischen Porträtkunst". Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Römische Abteilung (in German). 92. Verlag Philipp von Zabern. ISSN 0342-1287.

- Parlasca, Klaus (1989). "Palmyrenische Bildnisse aus dem Umkreis Zenobias". In Dahlheim, Werner; Shuller, Wolfgang; von Ungern-Sternberg, Jürgen (eds.). Festschrift Robert Werner: zu Seinem 65. Geburtstag Dargebracht von Freunden, Kollegen und Schülern. Xenia: Konstanzer Althistorische Vorträge und Forschungen (in German). Vol. 22. Universitätsverlag Konstanz. pp. 205–211. ISBN 978-3-879-40356-1.

- Potter, David S (2014). The Roman Empire at Bay, AD 180–395. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-69477-8.

- Poulsen, Poul Frederik Sigfred (1921). Wrange, Ewert; Hazelius, Fritjof (eds.). "De Palmyrenske Skulpturer". Tidskrift för Konstvetenskap (in Danish). 6. Aktiebolaget Skånska Centraltryckeriet. OCLC 64210828.

- Rostovtzeff, Michael (1943). "Res Gestae Divi Saporis and Dura". Berytus Archeological Studies. 8. The Museum of Archeology of The American University of Beirut. ISSN 0067-6195.

- Sartre, Maurice (2005). "The Arabs and the Desert Peoples". In Bowman, Alan K.; Garnsey, Peter; Cameron, Averil (eds.). The Crisis of Empire, AD 193–337. The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 12. Cambridge University Press. pp. 498–520. ISBN 978-0-521-30199-2.

- Simonsen, David Jakob (1889). Sculptures et Inscriptions de Palmyre à la Glyptothèque de Ny Calsberg (in French). Th. Lind. OCLC 2047359.

- Southern, Patricia (2008). Empress Zenobia: Palmyra's Rebel Queen. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-4411-4248-1.

- Stoneman, Richard (1994). Palmyra and Its Empire: Zenobia's Revolt Against Rome. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-08315-2.

- Strong, Donald Emrys (1995) [1976]. Toynbee, Jocelyn Mary Catherine; Ling, Roger (eds.). Roman Art. Pelican History of Art. Vol. 44. Yale University Press. ISSN 0553-4755.

- Teixidor, Javier (2005). "Palmyra in the Third Century". In Cussini, Eleonora (ed.). A Journey to Palmyra: Collected Essays to Remember Delbert R. Hillers. Brill. pp. 181–226. ISBN 978-90-04-12418-9.

- Vlizos, Stavros (2001). "Syrische Porträtplastik im Benaki Museum (Athen)". Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Athenische Abteilung (in German). 116. Verlag Philipp von Zabern. ISSN 0342-1325.

- Wadeson, Lucy (2014). "Funerary Portrait of a Palmyrene Priest". Records of the Canterbury Museum. 28. Canterbury Museum: 49–59. ISSN 0370-3878.

- Wielgosz, Dagmara (2010). "La Sculpture en Marbre à Palmyre" (PDF). Studia Palmyreńskie (in French). 11. Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology, University of Warsaw. ISSN 0081-6787.

- Young, Gary K. (2003) [2001]. Rome's Eastern Trade: International Commerce and Imperial Policy 31 BC – AD 305. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-54793-7.

External links

- One of the three portraits in the Palmyra museum from the hexagonal tomb (code B2727/9127), on the Getty Images website.

- The portrait in the Palmyra museum (Code Inv. B 2186-CD 134,62), from a 1964 archaeological report hosted on the Heidelberg University website. It is very similar to the Damascus portrait (C1519) and was apparently produced in the same workshop.