Portuguese maritime exploration

Portuguese maritime exploration resulted in the numerous territories and maritime routes recorded by the Portuguese as a result of their intensive maritime journeys during the 15th and 16th centuries. Portuguese sailors were at the vanguard of European exploration, chronicling and mapping the coasts of Africa and Asia, then known as the East Indies, and Canada and Brazil (the West Indies), in what came to be known as the Age of Discovery.

Methodical expeditions started in 1419 along West Africa's coast under the sponsorship of prince

History

Origins

In 1297, King

In 1317, King Dinis made an agreement with Genoese merchant sailor Manuel Pessanha (Pessagno), appointing him first Admiral with trade privileges with his homeland in return for twenty warships and crews, with the goal of defending the country against Muslim pirate raids, thus laying the basis for the Portuguese Navy and establishment of a Genoese merchant community in Portugal.[4] Forced to reduce their activities in the Black Sea, the Republic of Genoa had turned to North Africa for trade in wheat and olive oil and a search for gold – navigating also into the ports of Bruges (Flanders) and England. Genoese and Florentine communities were established in Portugal, which profited from the enterprise and financial experience of these rivals of the Republic of Venice.[citation needed]

In the second half of the fourteenth century outbreaks of bubonic plague led to severe depopulation: the economy was extremely localized in a few towns, and migration from the country led to the abandonment of agricultural land and an increase in rural unemployment. Only the sea offered opportunities, with most people settling in fishing and trading areas along the coast.[5] Between 1325 and 1357 Afonso IV of Portugal granted public funding to raise a proper commercial fleet and ordered the first maritime explorations, with the help of Genoese, under command of admiral Manuel Pessanha. In 1341 the Canary Islands, already known to Genoese seafarers, were officially discovered under the patronage of the Portuguese king, but in 1344 Castile disputed ownership of them, further propelling the Portuguese naval efforts.[6]

Atlantic exploration (1418–1488)

In 1415, the Portuguese occupied the North African city of

In 1418, two of Henry's captains,

A Portuguese attempt to capture

At around the same time as the unsuccessful attack on the Canary Islands, the Portuguese began to explore the North African coast. Sailors feared what lay beyond Cape Bojador at the time, as Europeans did not know what lay beyond on the African coast, and did not know whether it was possible to return once it was passed. Henry wished to know how far the Muslim territories in Africa extended, and whether it was possible to reach the source of the lucrative tran-Saharan caravan gold trade and perhaps to join forces with the long-lost Christian kingdom of Prester John that was rumoured to exist somewhere to the east.[10][11]

In 1434, one of Prince Henry's captains, Gil Eanes, passed this obstacle. Once this psychological barrier had been crossed, it became easier to probe further along the coast.[12] Within two decades of exploration, Portuguese ships had bypassed the Sahara. Westward exploration continued over the same period: Diogo de Silves discovered the Azores island of Santa Maria in 1427 and in the following years Portuguese mariners discovered and settled the rest of the Azores.

Henry suffered a serious setback in 1437 after

In 1443,

The caravel, an existing ship type, was used in exploration from about 1440. It had a number of advantageous characteristics. These included shallow draft, which was suitable for approaching unknown coasts, and an efficient combination of hull shape (including a rudder attached to the sternpost, unlike some other contemporary types with side-mounted steering oars) and lateen rig, which gave a fast-sailing vessel which had better windward sailing ability than other vessels of the time.[13]

Portuguese navigators reached ever more southerly

Exploration after Prince Henry

As a result of the first meager returns of the African explorations, in 1469 king

In 1471, Gomes' explorers reached

In 1482, Diogo Cão discovered the mouth of the Congo River. In 1486, Cão continued to Cape Cross, in present-day Namibia, near the Tropic of Capricorn.

In 1488, Bartolomeu Dias rounded the Cape of Good Hope near the southern tip of Africa, disproving the view that had existed since Ptolemy that the Indian Ocean was separate from the Atlantic. Also at this time, Pêro da Covilhã reached India via Egypt and Yemen, and visited Madagascar. He recommended further exploration of the southern route.[20]

As the Portuguese explored the coastlines of Africa, they left behind a series of padrões, stone crosses inscribed with the Portuguese coat of arms marking their claims,[21] and built forts and trading posts. From these bases, the Portuguese engaged profitably in the slave and gold trades. Portugal enjoyed a virtual monopoly of the Atlantic slave trade for over a century, exporting around 800 slaves annually. Most were brought to the Portuguese capital Lisbon, where it is estimated black Africans came to constitute 10 percent of the population.[22]

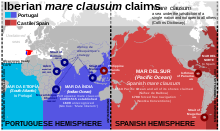

Tordesillas division of the world (1492)

In 1492 Christopher Columbus's discovery for Spain of the New World, which he believed to be Asia, led to disputes between the Spanish and Portuguese. These were eventually settled by the Treaty of Tordesillas in 1494 which divided the world outside of Europe in an exclusive duopoly between the Portuguese and the Spanish, along a north–south meridian 370 leagues, or 970 miles (1,560 km), west of the Cape Verde islands. However, as it was not possible at the time to correctly measure longitude, the exact boundary was disputed by the two countries until 1777.[23]

The completion of these negotiations with Spain is one of several reasons proposed by historians for why it took nine years for the Portuguese to follow up on Dias's voyage to the Cape of Good Hope, though it has also been speculated that other voyages were, in fact, taking place in secret during this time.[24][25] Whether or not this was the case, the long-standing Portuguese goal of finding a sea route to Asia was finally achieved in a ground-breaking voyage commanded by Vasco da Gama.

Reaching India and Brazil (1497–1500)

Vasco da Gama's squadron left Portugal on 8 July 1497, consisting of four ships and a crew of 170 men. It rounded the Cape and continued along the coast of Southeast Africa, where a local pilot was brought on board who guided them across the Indian Ocean, reaching Calicut in western India in May 1498.[26] After some conflict, da Gama got an ambiguous letter for trade with the Zamorin of Calicut, leaving there some men to establish a trading post.

Vasco da Gama's voyage to Calicut was the starting point for deployment of Portuguese feitoria posts along the east coast of Africa and in the Indian Ocean.[27] Shortly after, the Casa da Índia was established in Lisbon to administer the royal monopoly of navigation and trade. Exploration soon lost private support, and took place under the exclusive patronage of the Portuguese Crown.

The second voyage to India was dispatched in 1500 under

Indian Ocean explorations (1497–1542)

The aim of Portugal in the Indian Ocean was to ensure the monopoly of the

In 1500, the second fleet to India (which also made landfall in Brazil) explored the East African coast in

Profiting from the rivalry between the Maharaja of Kochi and the

In 1502 Vasco da Gama took the island of Kilwa on the coast of Tanzania, where in 1505 the first fort of Portuguese East Africa was built to protect ships sailing in the East Indian trade.In 1505, king

In 1506, a Portuguese fleet under the command of

In 1509, the Portuguese won the sea

Under the government of Albuquerque,

Southeast Asia expeditions

In April 1511 Albuquerque sailed to Malacca in modern-day Malaysia,[36] the most important eastern point in the trade network, where Malay met Gujarati, Chinese, Japanese, Javanese, Bengali, Persian and Arabic traders, described by Tomé Pires as invaluable. The port of Malacca became then the strategic base for Portuguese trade expansion with China and Southeast Asia, under the Portuguese rule in India with its capital at Goa. To defend the city a strong fort was erected, called the "A Famosa", where one of its gates still remains today. Learning of Siamese ambitions over Malacca, Albuquerque immediately sent Duarte Fernandes on a diplomatic mission to the kingdom of Siam (modern Thailand), where he was the first European to arrive, establishing amicable relations between the two kingdoms.[37] In November that year, getting to know the location of the so-called "Spice Islands" in the Moluccas, Albuquerque sent an expedition to find them. Led by António de Abreu, the expedition arrived in early 1512. Abreu went by Ambon, while his deputy commander Francisco Serrão advanced to Ternate, where a Portuguese fort was allowed. That same year, in Indonesia, the Portuguese took Makassar, reaching Timor in 1514. Departing from Malacca, Jorge Álvares came to southern China in 1513. This visit followed the arrival in Guangzhou, where trade was established. Later a trading post at Macau would be established.

The Portuguese empire expanded into the Persian Gulf as Portugal contested control of the spice trade with the

In 1525, after

In 1530,

In 1534, Gujarat was occupied by the

In 1538 the fortress of Diu was again surrounded by Ottoman ships. Another siege failed in 1547, putting an end to Ottoman ambitions and confirming Portuguese hegemony.

In 1542 Jesuit missionary

Portugal established trading ports at far-flung locations like

Cartographic history

Map of Portuguese exploration and discoveries (1415–1543)

Portuguese nautical science

Chronology

- 1147—Voyage of the Adventurers. Just before the siege of Lisbon by Afonso I of Portugal, a Muslim expedition left in search of legendary islands offshore. They were never heard from again.[42]

- 1336—Possibly the first expedition to the Canary Islands with additional expeditions in 1340 and 1341, though this is disputed.[43]

- 1412—Prince Henry, the Navigator, orders the first expeditions to the African Coast and Canary Islands.

- 1415—Conquest of Ceuta(North Africa)

- 1419—Porto Santo island, in the Madeira group.

- 1420—The same sailors and Bartolomeu Perestrelo discovered the island of Madeira, which began to be colonized at once.

- 1422—Cape Nao, the limit of Moorish navigation, is passed as the African Coast is mapped.

- 1427—Diogo de Silves discovered the Azores, which was colonized in 1431 by Gonçalo Velho Cabral.

- 1434—Gil Eanes sailed round Cape Bojador, thus destroying the legends of the ‘Dark Sea’.

- 1434—the 32 point compass-card replaces the 12 points used until then.

- 1435—Gil Eanes and Afonso Gonçalves Baldaia discovered Garnet Bay (Angra dos Ruivos) and the latter reached the Gold River (Rio de Ouro).

- 1441—Nuno Tristão reached Cape White.

- 1443—Nuno Tristão penetrated the Arguim Gulf. Prince Pedro granted Henry the Navigator the monopoly of navigation, war and trade in the lands south of Cape Bojador.

- 1444—Dinis Dias reached Cape Green (Cabo Verde).

- 1445—Álvaro Fernandes sailed beyond Cabo Verde and reached Cabo dos Mastros (Cape Naze).

- 1446—Álvaro Fernandes reached the northern Part of Portuguese Guinea (Guinea-Bissau).

- 1452—Diogo de Teive discovers the Islands of Flores and Corvo.

- 1455—Papal bull Romanus Pontifex confirmed the Portuguese explorations and declares that all lands and waters south of Bojador and cape Non (Cape Chaunar) belong to the kings of Portugal.

- 1456—Luis Cadamostodiscovers the first Cape Verde Islands.

- 1458—Three capes discovered and named along the Grand Cape Mount, Cape Mesurado and Cape Palmas).

- 1460—Death of Prince Henry, the Navigator. His systematic mapping of the Atlantic, reached 8° N on the African Coast and 40° W in the Atlantic (Sargasso Sea) in his lifetime.

- 1461—Diogo Gomes and Cape Verde Islands.

- 1461—Diogo Afonso discovered the western islands of the Cabo Verde group.

- 1471—Southern Cross. The discovery of the islands of São Tome and Principeis also attributed to these same sailors.

- 1479—Treaty of Alcáçovas establishes Portuguese control of the Azores, Guinea, ElMina, Madeira and Cape Verde Islands and Castilian control of the Canary Islands.

- 1482—Diogo Cão reached the estuary of the Zaire (Congo) and placed a landmark there. Explored 150 km upriver to the Yellala Falls.

- 1484—Diogo Cão reached Walvis Bay, south of Namibia.

- 1487—Pero da Covilhã traveled overland from Lisbon in search of the Kingdom of Prester John. (Ethiopia)

- 1488—Bartolomeu Dias, crowning 50 years of effort and methodical expeditions, rounded the Cape of Good Hope and entered the Indian Ocean. They had found the "Flat Mountain" of Ptolemy's Geography.

- 1489/92—South Atlantic Voyages to map the winds

- 1490—Columbus leaves for Spain after his father-in-law's death.

- 1492—First exploration of the Indian Ocean.

- 1494—The Treaty of Tordesillas between Portugal and Spain divided the world into two parts, Spain claiming all non-Christian lands west of a north–south line 370 leagues west of the Azores, Portugal claiming all non-Christian lands east of that line.

- 1495—Voyage of (lavrador, farmer)

- 1494—First boats fitted with cannon doors and topsails.

- 1498—Vasco da Gama led the first fleet around Africa to India, arriving in Calicut.

- 1498—Duarte Pacheco Pereira explores the South Atlantic and the South American Coast North of the Amazon River.

- 1500—Pedro Álvares Cabral discovered Brazil on his way to India.

- 1500—Gaspar Corte-Real made his first voyage to Newfoundland, formerly known as Terras Corte-Real.[citation needed]

- 1500—Diogo Dias discovered an island they named after St Lawrence after the saint on whose feast day they had first sighted the island later known as Madagascar.

- 1502— Returning from India, Vasco da Gama discovers the Amirante Islands (Seychelles).

- 1502—Fernão de Noronhadiscovered the island which still bears his name.

- 1503—On his return from the East, Estêvão da Gama discovered Saint Helena Island.

- 1505—Gonçalo Álvares in the fleet of the first viceroy sailed south in the Atlantic to were "water and even wine froze" discovering an island named after him, modern Gough Island.

- 1505—Lourenço de Almeida made the first Portuguese voyage to Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and established a settlement there.[44]

- 1506—Tristão da Cunha discovered the island that bears his name. Portuguese sailors landed on Madagascar.

- 1509—The Bay of Bengal crossed by Diogo Lopes de Sequeira. On the crossing he also reached Malacca.

- 1511— Duarte Fernandes is the first European to visit the Kingdom of Siam (Thailand), sent by Afonso de Albuquerque after the conquest of Malaca.[37]

- 1511–12 – João de Lisboa and Estevão de Fróis discovered the "Cape of Santa Maria" (

- 1512— Moluccas.

- 1512—Pedro Mascarenhas discover the island of Diego Garcia, he also encountered the Mauritius, although he may not have been the first to do so; expeditions by Diogo Dias and Afonso de Albuquerque in 1507 may have encountered the islands. In 1528 Diogo Rodrigues named the islands of Réunion, Mauritius, and Rodrigues the Mascarene Islands, after Mascarenhas.

- 1513—The first European trading ship to touch the coasts of China, under Jorge Álvares and Rafael Perestrello later in the same year.

- 1514–1531— António Fernandes's voyage and discoveries in 1514–1515,Monomotapa).

- 1517—Ming Dynasty during the reign of the Zhengde Emperor.

- 1519–1521—Indonesian Archipelago or the Moluccas (1511–1512), like Ferdinand Magellan in the 7th Portuguese India Armada under the command of Francisco de Almeida and on the expeditions of Diogo Lopes de Sequeira, Afonso de Albuquerque and his other voyages, sailing eastward from Lisbon (as Magellan in 1505), and then later, in 1521, sailing westward from Seville, reaching that longitude and region once again and then proceeding still further west.

- 1525—Aleixo Garcia explored the Rio de la Plata in service to Spain as a member of the expedition of Juan Díaz de Solís in 1516. Solís had left Portugal towards Castile (Spain) in 1506 and would be financed by Christopher de Haro, who had served Manuel I of Portugal until 1516. Serving Charles I of Spain after 1516, Haro believed that Lisboa and Frois had discovered a major route in the Southern New World to west or a strait to Asia two years earlier. Later (when returning and after a shipwreck on the coast of Brazil), from Santa Catarina, Brazil, and leading an expedition of some European and 2,000 Guaraní Indians, Aleixo Garcia explored Paraguay and Bolivia using the trail network Peabiru. Aleixo Garcia was the first European to cross the Chaco and even managed to penetrate the outer defenses of the Inca Empire on the hills of the Andes (near Sucre), in present-day Bolivia. He was the first European to do so, accomplishing this eight years before Francisco Pizarro.

- 1525—Aru Islands. The Ins des hobres blancos (Islands of the White Men) correspond, as far as locality is concerned, to the Arru (Aru) Islands. It would appear then that Gomes de Sequeira's Islands, which are the south-easternmost of those represented, must correspond with the Timor Laut group. In the same year, according to the voyages to the Banda Islands mentioned on Decadas and according to contemporaneous cartographers, Martim Afonso de Melo (Jusarte) and Garcia Henriques explored the Tanimbar Islands(the archipelago labelled "aqui invernou Martim Afonso de Melo" and "Aqui in bernon Martin Afonso de melo" [Here wintered Martin Afonso de Melo]) and probably the Aru Islands (the two archipelagos and the navigator mentioned in the maps of Lázaro Luís, 1563, Bartolomeu Velho, c. 1560, Sebastião Lopes, c. 1565 and also in the 1594 map of the East Indies entitled Insulce Molucoe by the Dutch cartographer Petrus Plancius and in the map of Nova Guinea of 1600).

- 1526—Discovery of Jorge de Meneses

- 1528—Rodrigues[48]

- 1529—Treaty of Saragossadivides the eastern hemisphere between Spain and Portugal, stipulating that the dividing line should lie 297.5 leagues or 17° east of the Moluccas.

- 1542–43—Fernão Mendes Pinto, António Mota and Francisco Zeimoto reached Japan.

- 1542—The coast of João Rodrigues Cabrilhoon behalf of Spain.

- 1557—pirates who infested the South China Sea.

- 1559—The Nau São Paulo commanded by Rui Melo da Câmara (was part of the Portuguese India Armada commanded by Jorge de Sousa) discovered Île Saint-Paul in the South Indian Ocean. The island was mapped, described and painted by members of the crew, among them the Father Manuel Álvares and the chemist Henrique Dias (Álvares and Dias calculated the correct latitude 38° South at the time of discovery). The Nau São Paulo, who also carried women and had sailed from Europe and had scale in Brazil, would be the protagonist of a dramatic and moving story of survival after sinking south of Sumatra.

- 1560—Monomotapa which appears to have been the N'Pande kraal, close by the M'Zingesi River, a southern tributary of the Zambezi. He arrived there on 26 December 1560.

- 1586— (now Cambodia).

- 1602–1606—Jesuit missionary, was the first known European to travel overland from India to China, via Afghanistan and the Pamirs.

- 1606—Pedro Fernandes de Queirós discovered Henderson Island, the Ducie Island and the islands later called the New Hebrides and now the nation of Vanuatu. Queirós landed on a large island which he took to be part of the southern continent, and named it La Austrialia del Espiritu Santo (The Australian Land of the Holy Spirit), for King Philip III(II), or Australia of the Holy Spirit (Australia do Espírito Santo) of the southern continent.

- 1626—Estêvão Cacella, Jesuit missionary, traveled through the Himalayas and was the first European to enter Bhutan.[49]

- 1636–1638—Belém do Pará up the Amazon River and reached Quito, Ecuador, in an expedition of over a thousand men. So Teixeira's expedition became the first simultaneously to travel up and down the Amazon River.

- 1648–1651—António Raposo Tavares with 200 whites from São Paulo and over a thousand Indians travelled for over 10,000 kilometres (6,200 mi), in the biggest expedition ever made in the Americas, following the courses of the rivers, most notably the Paraguay River, to the Andes, the Grande River, the Mamoré River, the Madeira River and the Amazon River. Only Tavares, 59 whites and some Indians reached Belém at the mouth of the Amazon River.

References

- ISBN 978-0-19-521921-0.

- ISBN 978-1-57607-335-3.

- ISBN 0-299-05584-1

- ISBN 0-8166-0782-6

- ISBN 0-415-23979-6

- ^ Butel, Paul, "The Atlantic", p. 36, Seas in history, Routledge, 1999

ISBN 0-415-10690-7

- ^ Diffie, p. 56

- ^ Diffie, p. 57–58

- ^ Diffie, p. 60

- ^ Rafiuddin Shirazi, Tazkiratul Mulk.

- ^ Anderson, p. 50

- ^ Diffie, p. 68

- ^ ISBN 0851775608.

- ^ Anderson, p. 44

- ISBN 3-87294-202-6.

- ^ Russell-Wood, p. 9

- ^ Thorn, Rob. "Discoveries After Prince Henry". Retrieved 2006-12-24.

- ^ Semedo, J. de Matos. "O Contrato de Fernão Gomes" (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on 2013-12-03. Retrieved 2006-12-24.

- ^ "Castelo de Elmina". Governo de Gana. Archived from the original on 2007-03-05. Retrieved 2006-12-24.

- ^ Anderson, p. 59

- ^ Newitt, p. 47

- ^ Anderson, p. 55

- ^ Diffie, p. 174

- ^ Diffie, p. 176

- ^ Boxer, p. 36

- ^ Scammell, p. 13

- ISBN 0-415-09085-7.

- ^ McAlister, p. 75

- ^ McAlister, p. 76

- ISBN 978-0-521-84644-8.

- ^ "St. Francis Church". Wonderful Kerala. Retrieved 2008-02-21.

- ISBN 81-902505-2-3.

- ^ "European Encroachment and Dominance:The Portuguese". Sri Lanka: A Country Study. Retrieved 2006-12-02.

- )

- ^ Indo-Portuguese Issues Indo-Portuguese Issues

- ISBN 0-333-57689-6.

- ^ ISBN 0-226-46731-7.

- ISBN 978-1-86064-736-9.

- ISBN 1-74059-421-5.

- ISBN 0-262-66072-5.

- ISBN 0-415-32379-7.

- ^ Mohammed Hamidullah (Winter 1968). "Muslim Discovery of America before Columbus", Journal of the Muslim Students' Association of the United States and Canada 4 (2): 7–9 [1]

- ^ B. W. Diffie, Foundations of the Portuguese Empire, 1415 -1580, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, p. 28.

- ^ This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wood, James, ed. (1907). The Nuttall Encyclopædia. London and New York: Frederick Warne.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Newen Zeytung auss Presillg Landt

- ^ Bethell, Leslie (1984). The Cambridge History of Latin America, Volume 1, Colonial Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 257.[2]

- ^ [3] Rhodesiana: The Pioneer Head

- ISBN 81-206-0207-2.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-08-29. Retrieved 2010-02-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) FATHER ESTEVAO CACELLA'S REPORT ON BHUTAN IN 1627.

Further reading

- Abernethy, David (2000). The Dynamics of Global Dominance, European Overseas Empires 1415–1980. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09314-4.

- Anderson, James Maxwell (2000). The History of Portugal. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-31106-4.

- ISBN 0-09-131071-7.

- Boyajian, James (2008). Portuguese Trade in Asia Under the Habsburgs, 1580–1640. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8754-3.

- Davies, Kenneth Gordon (1974). The North Atlantic World in the Seventeenth Century. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-0713-3.

- Diffie, Bailey (1977). Foundations of the Portuguese Empire, 1415–1580. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-0782-6.

- Diffie, Bailey (1960). Prelude to empire: Portugal overseas before Henry the Navigator. U of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-5049-5.

- Lockhart, James (1983). Early Latin America: A History of Colonial Spanish America and Brazil. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-29929-2.

- McAlister, Lyle (1984). Spain and Portugal in the New World, 1492–1700. University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-1216-1.

- Newitt, Malyn D.D. (2005). A History of Portuguese Overseas Expansion, 1400–1668. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-23979-6.

- Russell-Wood, A.J.R. (1998). The Portuguese Empire 1415–1808. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-5955-7.

- Scammell, Geoffrey Vaughn (1997). The First Imperial Age, European Overseas Expansion c.1400–1715. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-09085-7.