Positive psychology

| Part of a series on |

| Psychology |

|---|

Positive psychology studies the conditions that contribute to the optimal functioning of people, groups, and institutions.[1] It studies "positive subjective experience, positive individual traits, and positive institutions... it aims to improve quality of life."[2]

Positive psychology began as a new domain of

Positive psychology largely relies on concepts from the Western philosophical tradition, such as the Aristotelian concept of eudaimonia,[6] which is typically rendered in English with the terms "flourishing", "the good life" or "happiness".[7] Positive psychologists study empirically the conditions and processes that contribute to flourishing, subjective well-being, and happiness,[1] often using these terms interchangeably.

Positive psychologists suggest a number of factors that may contribute to happiness and subjective well-being, for example: social ties with a spouse, family, friends, colleagues, and wider networks; membership in clubs or social organizations; physical exercise; and the practice of meditation.[8] Spiritual practice and religious commitment is another possible source for increased well-being.[9] Happiness may rise with increasing income, though it may plateau or even fall when no further gains are made or after a certain cut-off amount.[10]

Definition and basic assumptions

Definition

Martin Seligman and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi define positive psychology as "the scientific study of positive human functioning and flourishing on multiple levels that include the biological, personal, relational, institutional, cultural, and global dimensions of life."[11]

Basic concepts

Positive psychology concerns eudaimonia, a word that means human thriving or flourishing.[12][page needed] A "good life" is defined by psychologists and philosophers as consisting of authentic expression of self, a sense of well-being, and active engagement in life.[13]

Positive psychology aims to complement and extend traditional problem-focused psychology. It concerns positive states (e.g. happiness), positive traits (e.g. talents, interests, strengths of character), positive relationships, and positive institutions and how these apply to physical health.[14]

Seligman proposes that a person can best promote their well-being by nurturing their character strengths.[15] Seligman identifies other possible goals of positive psychology: families and schools that allow children to grow, workplaces that aim for satisfaction and high productivity, and teaching others about positive psychology.[16]

A basic premise of positive psychology is that human actions arise from our anticipations about the future; these anticipations are informed by our past experiences.[17]

Those who practice positive psychology attempt psychological interventions that foster positive attitudes toward one's subjective experiences, individual traits, and life events.[11] The goal is to minimize pathological thoughts that may arise in a hopeless mindset and to develop a sense of optimism toward life.[11] Positive psychologists seek to encourage acceptance of one's past, excitement and optimism about one's future, and a sense of contentment and well-being in the present.[18]

Happiness

Happiness can be defined in two general ways: an enjoyable state of mind, and the living of an enjoyable life.[19]

Quality of life

Quality of life is how well you are living and functioning in life. It encompasses more than just physical and mental well-being; it can also include socioeconomic factors. This term can be perceived differently in different cultures and regions around the world.[20]

Research topics

According to Seligman and Christopher Peterson, positive psychology addresses three issues: positive emotions,[21] positive individual traits,[22] and positive institutions.[23] Positive emotions concern being content with one's past, being happy in the present, and having hope for the future.[23][24] Positive individual traits are one's strengths and virtues. Positive institutions are strengths to better a community of people.[clarification needed][16]

According to Peterson, positive psychologists are concerned with four topics: positive experiences, enduring psychological traits, positive relationships, and positive institutions.

History

The positive psychology movement was first founded in 1998 by Martin Seligman. He was concerned about the fact that mainstream psychology was too focused on disease, disorders, and disabilities rather than wellbeing, resilience, and recovery. His goal was to apply the methodological, scientific, scholarly and organizational strengths of mainstream psychology to facilitate well-being rather than illness and disease.[27]

The field has been influenced by humanistic as well as psychodynamic approaches to treatment. Predating the use of the term "positive psychology", researchers within the field of psychology had focused on topics that would now be included under this new denomination.[28]

The term "positive psychology" dates at least to 1954, when

In the opening sentence of his book Authentic Happiness, Seligman claimed: "for the last half century psychology has been consumed with a single topic only—mental illness,"[32]: xi expanding on Maslow's comments.[33] He urged psychologists to continue the earlier missions of psychology of nurturing talent and improving normal life.[34]: 1–22

Development

The first positive psychology summit took place in 1999. The First International Conference on Positive Psychology took place in 2002.[34]: 1–22 In September 2005, the first master's program in applied positive psychology (MAPP) was launched at the University of Pennsylvania.[35] In 2006, a course on positive psychology at Harvard University was one of the most popular courses on offer.[36] In June 2009, the First World Congress on Positive Psychology took place in Philadelphia.[37]

The field of positive psychology today is most advanced in the United States, Canada, Western Europe, and Australia.[38][page needed]

Influences

Several humanistic psychologists, most notably Maslow, Carl Rogers, and Erich Fromm, developed theories and practices pertaining to human happiness and flourishing. More recently, positive psychologists have found empirical support for the humanistic theories of flourishing.

In 1984, psychologist

According to Corey Keyes, who collaborated with Carol Ryff and uses the term flourishing as a central concept, mental well-being has three components: hedonic (i.e. subjective or emotional[44]), psychological, and social well-being.[45] Hedonic well-being concerns emotional aspects of well-being, whereas psychological and social well-being, e.g. eudaimonic well-being, concerns skills, abilities, and optimal functioning.[46] This tripartite model of mental well-being has received cross-cultural empirical support.[44][46][47]

Influences in ancient history

Before the use of the term "positive psychology" there were researchers who focused on topics that would now be included under the umbrella of positive psychology.[28] Some view positive psychology as a meeting of Eastern thought, such as Buddhism, and Western psychodynamic approaches.[48]

The historical roots of positive psychology are found in the teachings of Aristotle, whose Nicomachean Ethics is a description of the theory and practice of human flourishing—which he referred to as eudaimonia—of the tutelage necessary to achieve it, and of the psychological obstacles to its practice.[49] It teaches the cultivation of virtues as the means of attaining happiness and well-being.[50]

Core theory and methods

There is no accepted "gold standard" theory in positive psychology. The work of Seligman is regularly quoted,[51] as is the work of Csikszentmihalyi, and older models of well-being, such as Ryff's six-factor model of psychological well-being and Diener's tripartite model of subjective well-being.

Later, Paul Wong introduced the concept of second-wave positive psychology.

Initial theory: three paths to happiness

In Authentic Happiness (2002) Seligman proposed three kinds of a happy life that can be investigated:[32]: 275 [51]

- Pleasant life: research into the pleasant life, or the "life of enjoyment", examines how people optimally experience, forecast, and savor the positive feelings and emotions that are part of normal and healthy living (e.g., relationships, hobbies, interests, entertainment, etc.). Seligman says this most transient element of happiness may be the least important.[52]

- Good Life: investigation of the beneficial effects of immersion, absorption, and flow felt by people when optimally engaged with their primary activities, is the study of the Good Life, or the "life of engagement". Flow is experienced when there is a match between a person's strengths and their current task, i.e., when one feels confident of accomplishing a chosen or assigned task. Related concepts include self-efficacy and play.

- Meaningful Life: inquiry into the meaningful life, or "life of affiliation", questions how people derive a positive sense of well-being, belonging, meaning, and purpose from being part of and contributing back to something larger and more enduring than themselves (e.g., nature, social groups, organizations, movements, traditions, belief systems).[53]

PERMA

In Flourish (2011), Seligman argued that the last category of his proposed three kinds of a happy life, "meaningful life", can be considered as three different categories. The resulting summary for this theory is the mnemonic acronym PERMA: Positive Emotions, Engagement, Relationships, Meaning and purpose, and Accomplishments.[51][54]

- Positive emotions

- include a wide range of feelings, not just happiness and joy,[55]: ch. 1 but excitement, satisfaction, pride, and awe, amongst others. These are connected to positive outcomes, such as longer life and healthier social relationships.[24]

- Engagement

- refers to involvement in activities that draw and build upon one's interests. Csikszentmihalyi explains true engagement as flow, a state of deep effortless involvement,[51] a feeling of intensity that leads to a sense of ecstasy and clarity.[56] The task being done must call upon a particular skill and it should be possible while being a little bit challenging. Engagement involves passion for and concentration on the task at hand—complete absorption and loss of self-consciousness.[55]: ch. 1

- Relationships

- are essential in fueling positive emotions,[27]whether they are work-related, familial, romantic, or platonic. As Peterson puts it, "other people matter."[57] Humans receive, share, and spread positivity to others through relationships. Relationships are important in bad times and good times. Relationships can be strengthened by reacting to one another positively. Typically positive things take place in the presence of other people.[58]

- Meaning

- is also known as purpose, and answers the question of "why?" Discovering a clear "why" puts everything into context from work to relationships to other parts of life.[27] Finding meaning is learning that there is something greater than oneself. Working with meaning drives people to continue striving for a desirable goal.

- Accomplishments

- are the pursuit of success and mastery.[55]: ch. 1 Unlike the other parts of PERMA, they are sometimes pursued even when accomplishments do not result in positive emotions, meaning, or relationships. Accomplishments can activate other elements of PERMA, such as pride, under positive emotion.[59] Accomplishments can be individual or community-based, fun-based, or work-based.

Each of the five PERMA elements was selected according to three criteria:

- It contributes to well-being.

- It is pursued for its own sake.

- It is defined and measured independently of the other elements.

Character Strengths and Virtues

The Character Strengths and Virtues (CSV) handbook (2004) was the first attempt by Seligman and Peterson to identify and classify positive psychological traits of human beings. Much like the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) of general psychology, the CSV provided a theoretical framework to assist in understanding strengths and virtues and for developing practical applications for positive psychology. It identified six classes of virtues (i.e., "core virtues"), underlying 24 measurable character strengths.[60]

The CSV suggested these six virtues have a historical basis in the vast majority of cultures and that they can lead to increased happiness when built upon. Notwithstanding numerous cautions and caveats, this suggestion of universality leads to three theories:[60]: 51

- The study of positive human qualities broadens the scope of psychological research to include mental wellness.

- The leaders of the positive psychology movement challenge moral relativism by suggesting people are "evolutionarily predisposed" toward certain virtues.

- Virtue has a biological basis.

The organization of the six virtues and 24 strengths is as follows:

- Humanity: love, kindness, social intelligence

- Justice: citizenship, fairness, leadership, integrity, excellence

- Temperance: forgiveness and mercy, humility, self-control

- Transcendence: humor, spirituality

Subsequent research challenged the need for six virtues. Instead, researchers suggested the 24 strengths are more accurately grouped into just three or four categories: Intellectual Strengths, Interpersonal Strengths, and Temperance Strengths,[61] or alternatively, Interpersonal Strengths, Fortitude, Vitality, and Cautiousness.[62] These strengths, and their classifications, have emerged independently elsewhere in literature on values. Paul Thagard described some examples.[63]

Flow

In the 1970s, Csikszentmihalyi began studying flow, a state of absorption in which one's abilities are well-matched to the demands at-hand. He often refers to it as "optimal experience".[64] Flow is characterized by intense concentration, loss of self-awareness, a feeling of being perfectly challenged (neither bored nor overwhelmed), and a sense that "time is flying." Flow is intrinsically rewarding; it can also assist in the achievement of goals (e.g., winning a game) or improving skills (e.g., becoming a better chess player).[65] Anyone can experience flow and it can be felt in different domains, such as play, creativity, and work.

Flow is achieved when the challenge of the situation meets one's personal abilities. A mismatch of challenge for someone of low skills results in a state of anxiety and feeling overwhelmed; insufficient challenge for someone highly skilled results in boredom.[65] A good example of this would be an adult reading a children's book. They would not feel challenged enough to be engaged or motivated in the reading. Csikszentmihalyi explained this using various combinations of challenge and skills to predict psychological states. These four states included the following:[66]

- Apathy

- low challenge and low skill(s)

- Relaxation

- low challenge and high skill(s)

- Anxiety

- high challenge and low skill(s)

- Flow

- high challenge and high skill(s)

Accordingly, an adult reading a children's book would most likely be in the relaxation state. The adult has no need to worry that the task will be more than they can handle. Challenge is a well-founded explanation for how one enters the flow state and employs intense concentration. However, other factors contribute. For example, one must be intrinsically motivated to participate in the activity/challenge. If the person is not interested in the task, then there is no possibility of their being absorbed into the flow state.[67]

Benefits

Flow can help in parenting children. When flow is enhanced between[clarification needed] parents and children, the parents can better thrive in their roles as a parents. A parenting style that is positively oriented[definition needed] results in children who experience lower levels of stress and improved well-being.[68]

Flow also has benefits in a school setting. When students are in a state of flow they are fully engaged, leading to better retention of information.

Most teachers and parents want students become more engaged and interested in the classroom. The design of the education system was not able to account for such needs.[73] One school implemented a program called PASS. They acknowledged that students needed more challenge and individual advancement; they referred to this as sport culture. This PASS program integrated an elective class into which students could immerse themselves. Such activities included self-paced learning, mastery-based learning, performance learning, and so on.[74]

Flow benefits general well-being. It is a positive and intrinsically motivating experience. It is known to "produce intense feelings of enjoyment".[67] It can improve our lives by making them happier and more meaningful. Csikszentmihalyi discovered that our personal growth and development generates happiness. Flow is positive experience because it promotes that opportunity for personal development.[75]

Negatives

While flow can be beneficial to students, students who experience flow can become overly focused on a particular task. This can lead to students neglecting other important aspects of their learning.[76]

In positive psychology there can be misunderstandings on what clinicians and people define as positive. In certain instances, positive qualities, such as optimism, can be detrimental to health, and therefore appear as a negative quality.[77] Alternatively, negative processes, such as anxiety, can be conducive to health and stability and thus would appear as positive qualities.[77] A second wave of positive psychology has further identified and characterized "positive" and "negative" complexes through the use of critical and dialectical thinking.[77] Researchers in 2016 chose to identify these characteristics via two complexes: post-traumatic growth and love as well as optimism vs. pessimism.[77]

Second-wave positive psychology

Paul Wong introduced the idea of a second wave of positive psychology, focused on the pursuit of meaning in life, which he contrasted with the pursuit of happiness in life.[78] Ivtzan, Lomas, Hefferon, and Worth have recast positive psychology as being about positive outcome or positive mental health, and have explored the positive outcomes of embracing negative emotions and pessimism.[79] Second-wave positive psychology proposes that it is better to accept and transform the meaning of suffering than it is to avoid suffering.[80]

In 2016, Lomas and Itzvan proposed that human flourishing (their goal for positive psychology) is about embracing dialectic interplay of positive and negative.[77] Phenomena cannot be determined to be positive or negative independent of context. Some of their examples included:

- the dialectic of optimism and pessimism

- Optimism is associated with longevity, but strategic pessimism can lead to more effective planning and decision making.

- the dialectic of self-esteem and humility

- Self-esteem is related to well-being, but pursuit of self-esteem can increase depression. Humility can be either low self-opinion or it can lead to prosocial action.

- the dialectic of forgiveness and anger

- Forgiveness has been associated with well-being, but people who are more forgiving of abuse may suffer prolonged abuse. While anger has been presented as a destructive emotion, it can also be a moral emotion and drawn upon to confront injustices.

In 2019, Wong proposed four principles of second-wave positive psychology:[80]

- accepting and confronting with courage the reality that life is full of evil and suffering

- sustainable wellbeing can only be achieved through overcoming suffering and the dark side of life

- recognizing that everything in life comes in polarities and the importance of achieving an adaptive balance through dialectics

- learning from indigenous psychology, such as the ancient wisdom of finding deep joy in bad situations

Second-wave positive psychology is sometimes abbreviated as PP 2.0.

Third-wave positive psychology

The third wave of positive psychology emphasizes going beyond the individual to take a deeper look at the groups and systems in which we live. It also promotes becoming more interdisciplinary and multicultural and incorporates more methodologies.[81]

In broadening the scope and exploring the systemic and socio-cultural dimensions of people's lived realities, there are four specific things to focus on:[77]

- The focus of enquiry: becoming more interested in emergent paradigms like "systems-informed positive psychology" which incorporates principles and concepts from the systems sciences to optimize human social systems and the individuals within them.[82]

- Disciplines: becoming more multi- and interdisciplinary, as reflected in hybrid formulations like positive education, which combines traditional education and research based ways of increasing happiness and overall well-being.[83]

- Cultural contexts: becoming more multicultural and global

- Methodologies: embracing other paradigms and ways of knowing, such as qualitative and mixed methods approaches rather than relying solely on quantitative research.

Research advances and applications

Subject-matter and methodology development expanded the field of positive psychology beyond its core theories and methods. Positive psychology is now a global area of study, with various national indices tracking citizens' happiness ratings.

Research findings

Research in positive psychology, well-being, eudaimonia and happiness, and the theories of Diener, Ryff, Keyes, and Seligman cover a broad range of topics including "the biological, personal, relational, institutional, cultural, and global dimensions of life."[11]

A meta-analysis of 49 studies showed that Positive Psychology Interventions (PPI) produced improvements in well-being and lower depression levels; the PPIs studied included writing gratitude letters, learning optimistic thinking, replaying positive life experiences, and socializing with others.[84] In a later meta-analysis of 39 studies with 6,139 participants, the outcomes were positive.[85] Three to six months after a PPI the effects on subjective well-being and psychological well-being were still significant. However the positive effect was weaker than in the earlier meta-analysis; the authors concluded that this was because they only used higher-quality studies. The PPIs they considered included counting blessings, kindness practices, making personal goals, showing gratitude, and focusing on personal strengths. Another review of PPIs found that over 78% of intervention studies were conducted in Western countries.[86]

In the textbook Positive Psychology: The Science of Happiness, authors Compton and Hoffman give the "Top Down Predictors" of well-being as high

In a study published in 2020, students were enrolled in a positive psychology course that focused on improving happiness and well-being through teaching about positive psychology.[88] The participants answered questions pertaining to the five PERMA categories. At the end of the semester those same students reported significantly higher scores in all categories (p<.001) except for engagement which was significant at p<.05. The authors stated, “Not only do students learn and get credit, there is also a good chance that many will reap the benefits in what is most important to them—their health, happiness, and well-being.”[88]

Academic methods

Quantitative

Quantitative methods in positive psychology include p-technique

Qualitative

Grant J. Rich explored the use of qualitative methodology to study positive psychology.[90] Rich addresses the popularity of quantitative methods in studying the empirical questions that positive psychology presents. He argues that there is an "overemphasis" on quantitative methods and suggests implementing qualitative methods, such as semi-structured interviews, observations, fieldwork, creative artwork, and focus groups. Rich states that qualitative approaches will further promote the "flourishing of positive psychology" and encourages such practice.[90]

Behavioral interventions

Changing happiness levels through interventions is a further methodological advancement in the study of positive psychology, and has been the focus of various academic and scientific psychological publications. Happiness-enhancing interventions include expressing kindness, gratitude, optimism, humility, awe, and mindfulness.

One behavioral experiment used two six-week interventions:[91] one involving the performance of acts of kindness, and one focused on gratitude which emphasized the counting of one's blessings. The study participants who went through the behavioral interventions reported higher levels of happiness and well-being than those who did not participate in either intervention.

Another study found that the interventions of expressing optimism and expressing gratitude enhanced subjective well-being in participants who took part in the intervention for eight months.[92] The researchers concluded that interventions are "most successful when participants know about, endorse, and commit to the intervention."[92] The article provides support that when people enthusiastically take part in behavioral interventions, such as expression of optimism and gratitude, they may increase happiness and subjective well-being.

Another study examined the interaction effects between gratitude and humility through behavior interventions.[93] The interventions were writing a gratitude letter and writing a 14-day diary. In both interventions, the researchers found that gratitude and humility are connected and are "mutually reinforcing."[93] The study also discusses how gratitude, and its associated humility, may lead to more positive emotional states and subjective well-being.

A series of experiments showed a positive effect of awe on subjective well-being.[94] People who felt awe also reported feeling they had more time, more preference for experiential expenditures than material expenditures, and greater life satisfaction. Experiences that heighten awe may lead to higher levels of life satisfaction and, in turn, higher levels of happiness and subjective well-being.

Mindfulness interventions may also increase subjective well-being in people who mindfully meditate.[95] Being mindful in meditation includes awareness and observation of one's meditation practice, with non-reactive and non-judgmental sentiments during meditation.

National indices of happiness

The creation of various national indices of happiness have expanded the field of positive psychology to a global scale.

In a January 2000 article in American Psychologist, psychologist Ed Diener argued for the creation of a national happiness index in the United States.[96] Such an index could provide measurements of happiness, or subjective well-being, within the United States and across many other countries in the world. Diener argued that national indices would be helpful markers or indicators of population happiness, providing a sense of current ratings and a tracker of happiness across time. Diener proposed that the national index include various sub-measurements of subjective well-being, including "pleasant affect, unpleasant affect, life satisfaction, fulfillment, and more specific states such as stress, affection, trust, and joy."[96]

In 2012, the first

The first World Happiness Report, published in 2012, detailed the state of world happiness, the causes of happiness and misery, policy implications from happiness reports, and three case studies of subjective well-being for 1) Bhutan and its Gross National Happiness index, 2) the U.K. Office for National Statistics Experience, and 3) happiness in the member countries within the OECD.[98]

The 2020 World Happiness Report, the eighth in the series of reports, was the first to include happiness rankings of cities across the world, in addition to rankings of 156 countries. The city of Helsinki, Finland was reported as the city with the highest subjective well-being ranking,[99] and the country of Finland was reported as the country with the highest subjective well-being ranking.[100] The 2020 report provided insights on happiness based on environmental conditions, social conditions, urban-rural happiness differentials, and sustainable development.[97] It also provided possible explanations for why Nordic countries have consistently ranked in the top ten happiest countries in the World Happiness Report, such as Nordic countries' high-quality government benefits and protections to its citizens, including welfare benefits and well-operated democratic institutions, as well as social connections, bonding, and trust.[101]

Additional national well-being indices and reported statistics include the Gallup Global Emotions Report,[102] Sharecare Community Well-Being Index,[103] Global Happiness Council's Global Happiness and Well-being Policy Report,[104] Happy Planet Index,[105] OECD Better Life Index,[106] and UN Human Development Reports.[107]

Influences on other academic fields

Positive psychology influenced other academic fields of study and scholarship, notably organizational behavior, education, and psychiatry.

Positive organizational scholarship

Positive organizational scholarship (POS), also referred to as positive organizational behavior (POB), began as an application of positive psychology to the field of organizational behavior. An early use of the term was in Positive Organizational Scholarship: Foundations of a New Discipline (2003), edited by Ross School of Business professors Kim S. Cameron, Jane E. Dutton, and Robert E. Quinn.[108] The editors promote "the best of the human condition", such as goodness, compassion, resilience, and positive human potential, as an organizational goal as important as financial success.[108] The goal of POS is to study the factors that create positive work experiences and successful, people-oriented outcomes.

The 2011 volume The Oxford Handbook of Positive Organizational Scholarship, covers such topics as positive human resource practices, positive organizational practices, and positive leadership and change. It applies positive psychology to the workplace context, covering areas such as positive individual attributes, positive emotions, strengths and virtues, and positive relationships.[109] The editors of that volume define POS this way:

Positive organizational scholarship rigorously seeks to understand what represents the best of the human condition based on scholarly research and theory. Just as positive psychology focuses on exploring optimal individual psychological states rather than pathological ones, organizational scholarship focuses attention on the generative dynamics in organizations that lead to the development of human strength, foster resiliency in employees, enable healing and restoration, and cultivate extraordinary individual and organizational performance. POS emphasizes what elevates individuals and organizations (in addition to what challenges them), what goes right in organizations (in addition to what goes wrong), what is life-giving (in addition to what is problematic or life-depleting), what is experienced as good (in addition to what is objectionable), and what is inspiring (in addition to what is difficult or arduous).[110]

Psychiatry

Positive psychology influenced psychiatry and led to more widespread promotion of practices including well-being therapy, positive psychotherapy, and an integration of positive psychology in therapeutic practice.[111]

Benefits of positive influences can be seen in practices like

Psychoanalysis can be used to treat mental illnesses such as depression as it focuses on identifying the conscious and unconscious motivations and behaviors affecting one's life. Treatment using psychoanalysis runs in a longer duration by practicing free association to promote personal growth.[116] Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), a common type of psychotherapy in America, focuses on both psychoanalysis and behavioral analysis: psychoanalysts focusing on conscious and unconscious motivations, behaviorists focusing on objectively measured behaviors. Therapy such as exposure therapy helps people with specific aspects of depression, or more specific cases like social phobia.[116]

Positive psychology may assist those recovering from traumatic brain injury (TBI).[117] TBI rehabilitation practices rely on bettering the patient's life by getting them to engage (or re-engage) in normal everyday practices, an idea which is related to tenets of positive psychology. While the empirical evidence for positive psychology is limited, positive psychology's focus on small successes, optimism, and prosocial behavior promises to improve the social and emotional well-being of TBI patients.

Popular culture

Positive psychology is a subject of popular books and films, and influences the wellness industry.

Books

Several popular psychology books have been written for a general audience.

Ilona Boniwell's Positive Psychology in a Nutshell provided a summary of the research. According to Boniwell, well-being is related to optimism, extraversion, social connections (i.e., close friendships), being married, having engaging work, religion or spirituality, leisure, good sleep and exercise, social class (through lifestyle differences and better coping methods), and subjective health (what you think about your health).[118] Boniwell writes that well-being is not related to age, physical attractiveness, money (once basic needs are met), gender (women are more often depressed but also more often joyful), educational level, having children, moving to a sunnier climate, crime prevention, housing, and objective health (what doctors say).

Sonja Lyubomirsky's The How of Happiness provides advice on how to improve happiness. According to this book, people should create new habits, seek out new emotions, use variety and timing to prevent hedonic adaptation, and enlist others to support the creation of those new habits.[119] Lyubomirsky recommends twelve happiness activities, including savoring life, learning to forgive, and living in the present.

Stumbling on Happiness by Daniel Gilbert shares positive psychology research suggesting that people are often poor at predicting what will make them happy and that people are prone to misevaluating the causes of their happiness.[120] He notes that the subjectivity of well-being and happiness often is the most difficult challenge to overcome in predicting future happiness, as our future selves may have different perspectives on life than our current selves.

Films

The film industry noticed positive psychology, and films have spurred new research within positive psychology.

Happy is a full-length documentary film covering positive psychology and neuroscience. It highlights case studies on happiness across diverse cultures and geographies. The film features interviews with notable positive psychologists and scholars, including Gilbert, Diener, Lyubomirsky, and Csikszentmihalyi.[121]

For several years, the Positive Psychology News website included a section on Positive Psychology Movie Awards that highlighted feature films that featured messages of positive psychology.[122]

The VIA Institute has researched positive psychology as represented in feature films. Contemporary and popular films that promote or represent character strengths are the basis for various academic articles.[123]

Wellness industry

The growing popularity and attention given to positive psychology research has influenced industry growth, development, and consumption of products and services meant to cater to wellness and well-being.

According to the Global Wellness Institute, as of 2020, the global wellness economy is valued at US$4.4 trillion;[124] the key sectors of the industry included Nutrition, Personal Care and Beauty, and Physical activity, while the Mental wellness and Public health sectors made up over US$0.5 billion.

Companies highlight happiness and well-being in their marketing strategies. Food and beverage companies such as Coca-Cola[125] and Pocky—whose motto is "Share happiness!"[126]—emphasize happiness in their commercials, branding, and descriptions. CEOs at retail companies such as Zappos have profited by publishing books detailing how they deliver happiness,[127] while Amazon's logo features a dimpled smile.[128]

Criticism

Many aspects of positive psychology have been criticized.

Reality distortion

In 1988, psychologists

Taylor and Brown suggest that positive illusions protect people from negative feedback that they might receive, and this, in turn, preserves their psychological adaptation and subjective well-being. However, later research found that positive illusions and related attitudes lead to psychological maladaptive conditions such as poorer social relationships, expressions of narcissism, and negative workplace outcomes,[130] thus reducing the positive effects that positive illusions have on subjective well-being, overall happiness, and life satisfaction.

Kirk Schneider, editor of the Journal of Humanistic Psychology, pointed to research showing high positivity correlates with positive illusion, which distorts reality. High positivity or flourishing could make one incapable of psychological growth, unable to self-reflect, and prone to holding racial biases. By contrast, negativity, sometimes evidenced in mild to moderate depression, is correlated with less distortion of reality. Therefore, Schneider argues, negativity might play an important role: engaging in conflict and acknowledging appropriate negativity, including certain negative emotions like guilt, might better promote flourishing. Schneider wrote: "perhaps genuine happiness is not something you aim at, but is... a by-product of a life well lived—and a life well lived does not settle on the programmed or neatly calibrated."[131]

Narrow focus

In 2003, Ian Sample noted that "Positive psychologists also stand accused of burying their heads in the sand and ignoring that depressed, even merely unhappy people, have real problems that need dealing with."

Psychological researcher Shelly Gable retorts that positive psychology is just bringing a balance to a side of psychology that is glaringly understudied. She points to imbalances favoring research into negative psychological well-being in cognitive psychology, health psychology, and social psychology.[132]

Psychologist Jack Martin maintains that positive psychology is not unique in its optimistic approach to emotional well-being, stating that other forms of psychology, such as counseling and educational psychology, are also interested in positive human fulfillment.[133] He says while positive psychology pushes for schools to be more student-centered and able to foster positive self-images in children, a lack of focus on self-control may prevent children from making full contributions to society. If positive psychology is not implemented correctly, it can cause more harm than good. This is the case, for example, when interventions in school are coercive (in the sense of being imposed on everyone without regard for the child's reason for negativity) and fail to take each student's context into account.[134]

Role of negativity

Barbara S. Held, a professor at Bowdoin College, argues that positive psychology has faults: negative side effects, negativity within the positive psychology movement, and the division in the field of psychology caused by differing opinions of psychologists on positive psychology. She notes the movement's lack of consistency regarding the role of negativity. She also raises issues with the simplistic approach taken by some psychologists in the application of positive psychology. A "one size fits all" approach is arguably not beneficial; she suggests a need for individual differences to be incorporated into its application.[135] By teaching young people that being confident and optimistic leads to success, when they are unsuccessful they may believe this is because they are insecure or pessimistic. This could lead them to believe that any negative internal thought or feeling they may experience is damaging to their happiness and should be steered clear of completely.[134]

Held prefers the Second Wave Positive Psychology message of embracing the dialectic nature of positive and negative, and questions the need to call it "positive" psychology.[135]

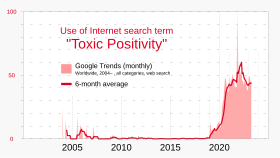

Toxic positivity

One critical response to positive psychology concerns "toxic positivity".

Methodological and philosophical critiques

Richard Lazarus critiqued positive psychology's methodological and philosophical components. He holds that giving more detail and insight into the positive is not bad, but not at the expense of the negative, because the two (positive and negative) are inseparable. Among his critiques:

- Positive psychology's use of correlational and cross-sectional research designs to indicate causality between the movement's ideas and healthy lives may hide other factors and time differences that account for observed differences.

- Emotions cannot be categorized dichotomously into positive and negative; emotions are subjective and rich in social/relational meaning. Emotions are fluid, meaning that the context they appear in changes over time. Lazarus states that "all emotions have the potential of being either one or the other, or both, on different occasions, and even on the same occasion when an emotion is experienced by different persons"[141]

- Individual differences are neglected in most social science research. Many research designs focus on the statistical significance of the groups while overlooking differences among people.

- Social science researchers' tend to not adequately define and measure emotions. Most assessments are quick checklists and do not provide adequate debriefing. Many researchers do not differentiate between fluid emotional states and relatively stable personality traits.

Lazarus holds that positive psychology claims to be new and innovative but the majority of research on stress and coping theory makes many of the same claims as positive psychology. The movement attempts to uplift and reinforce the positive aspects of one's life, but everyone in life experiences stress and hardship. Coping through these events should not be regarded as adapting to failures but as successfully navigating stress, but the movement doesn't hold that perspective.

Another critique of positive psychology is that it has been developed from a Eurocentric worldview. Intersectionality has become a methodological concern regarding studies within Positive Psychology.[142]

A literature review conducted in 2022 noted several criticisms of the area, including lack of conceptual thinking, problematic measurements, poor replication of results, self-isolation from mainstream psychology, decontextualization, and being used for capitalism.[143]

The US Army's Comprehensive Soldier Fitness program

The

Some psychologists criticized the CSF for various reasons. Nicholas J.L. Brown wrote: "The idea that techniques that have demonstrated, at best, marginal effects in reducing depressive symptoms in school-age children could also prevent the onset of a condition that is associated with some of the most extreme situations with which humans can be confronted is a remarkable one that does not seem to be backed up by empirical evidence."[147] Stephen Soldz of the Boston Graduate School of Psychoanalysis cited Seligman's acknowledgment that the CSF is a gigantic study rather than a program based on proven techniques, and questioned the ethics of requiring soldiers to participate in research without informed consent.[148] Soldz also criticized the CSF training for trying to build up-beat attitudes toward combat: "Might soldiers who have been trained to resiliently view combat as a growth opportunity be more likely to ignore or under-estimate real dangers, thereby placing themselves, their comrades, or civilians at heightened risk of harm?"[148]

In 2021 the

See also

- Precursors

- New Thought – 19th-century American spiritual movement

- Maslow's hierarchy of needs – Theory of developmental psychology

- Needs and Motives (Henry Murray)

- Self-determination theory – Macro theory of human motivation and personality

- Various

- Anatomy of an Epidemic – Work by Robert Whitaker

- Aversion to happiness – People wanting to deliberately avoid positive emotions and / or happiness

- Louise Burfitt-Dons – Activist, writer, blogger

- Community psychology – Branch of psychology

- Culture and positive psychology

- Happiness economics – Study of happiness and quality of life

- Meaning of life – Philosophical and spiritual question

- Pollyanna principle – Tendency to remember pleasant things better

- Positive education

- Positive neuroscience

- Positive psychotherapy – Psychotherapeutic method developed by Nossrat Peseschkian

- Positive youth development – type of development programme

- Posttraumatic growth– Psychological term

- Pragmatism – Philosophical tradition

- Psychological resilience – Ability to mentally cope with a crisis

- Rational ignorance – Practice of avoiding research whose cost exceeds its benefits

- Second wave positive psychology– Psychological approach

- Sex-positive movement – Ideology supporting healthy sexual norms

- Theory of humor– Conjectures explaining humor

Notes

References

- ^ S2CID 15186098.

- Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2021-03-06.

- OCLC 176182574.

- ^ a b Al Taher, Reham (2015-02-12). "The 5 Founding Fathers and A History of Positive Psychology". Positive Psychology. Retrieved 2022-12-06.

- ^ Peterson, Jordan. "Jordan Peterson explains Rogers' concept of 'incongruence'". YouTube.

- S2CID 144981682.

The science of psychology has been far more successful on the negative than on the positive side. It has revealed to us much about man's shortcomings, his illness, his sins, but little about his potentialities, his virtues, his achievable aspirations, or his full psychological height. It is as if psychology has voluntarily restricted itself to only half its rightful jurisdiction, the darker, meaner half.