Preening

Preening is a

Over time, some elements of preening have

Ingestion of pollutants or disease-causing organisms during preening can lead to problems ranging from liver and kidney damage to pneumonia and disease transmission. Injury and infection can cause overpreening in caged birds, as can confining a bird with a dominant or aggressive cage mate.

Etymology

The use of the word preen to mean the tidying of a bird's feathers dates from

Importance

Preening is a maintenance behaviour used by all birds to care for their feathers. It is an innate behaviour; birds are born knowing the basics, but there is a learned component. Birds that are hand-reared without access to a role model have abnormalities in their preening behaviours.

Because feathers are critical to a bird's survival – contributing to insulation, waterproofing and aerodynamic flight – birds spend a great deal of time maintaining them.[8] When resting, birds may preen at least once an hour.[9] Studies on multiple species have shown that they spend an average of more than 9% of each day on maintenance behaviours, preening occupying over 92% of that time, though this figure can be significantly higher.[10] Studies found that some gull species spent 15% of daylight hours during the breeding season preening, while another showed that common loons spent upwards of 25% of their day preening.[10][11] In most of the studied species where the bird's sex could be determined in the field, males spent more time preening than females, though this was reversed in ducks.[10] Some ratites, which are not dependent on their feathers for flight, spend far less time on maintenance behaviours. One study of ostriches found that they spent less than 1% of their time engaged in such behaviours.[12]

Preen oil

Fully grown feathers are essentially dead structures, so it is vital that birds have some way to protect and lubricate them. Otherwise, age and exposure cause them to become brittle.[13] To facilitate that care, many bird species have a preen or uropygial gland, which opens above the base of the tail feathers and secretes a substance containing fatty acids, water, and waxes. The bird gathers this substance on its bill and applies it to its feathers.[14] The gland is generally larger (in relation to body size) in waterbirds, including terns, grebes and petrels. However, studies have found no clear correlation between the size of the gland and the amount of time a species spends in the water; it is not consistently largest in those species that spend the most time in the water.[15]

Preen oil plays a role in reducing the presence of parasitic organisms, such as feather-degrading bacteria, lice and fungi, on a bird's feathers.

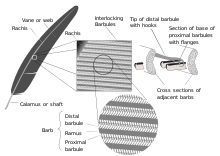

Preen oil helps to maintain the waterproofing of a bird's plumage. Though the oil does not provide any direct waterproofing agent, it helps to extend the life of the feather – including the microscopic structures (the barbs and barbules) which interlock to create the waterproof barrier.[6]

While most species have a preen gland, the organ is missing in the ratites (

Preening action

A bird's plumage is primarily made up of two feather types: firm

Birds cannot use their beaks to apply preen oil to their own heads. Instead, many use their feet in an action called scratch-preening. Once they have gathered preen oil on their beak, they scrape a foot across their bill to transfer the oil, and then scratch the oil into the feathers on their head.

Preening is often done in association with other maintenance behaviours, including bathing,

Secondary functions

Preening may help to send sexual signals to potential mates because plumage colouration (which can be altered by the act of preening) can reliably reflect the health or "quality" of its bearer.[38] In some species, preen oil is used to cosmetically colour the plumage. During the breeding season, the preen oil of the great white pelican becomes red-orange, imparting a pink flush to the bird's plumage.[38] The preen oil of several gull and tern species, including Ross's gull, contains a pink colourant which does the same. The heads of these birds typically show little pink, because of the difficulty of reaching those areas with preen oil.[39] The yellow feathers of the great hornbill are also cosmetically coloured during preening.[38] The preen oil of the Bohemian waxwing increases the UV reflectance of its feathers.[40] Ritualised preening is used in courtship displays by several species, particularly ducks; such preening is typically designed to draw attention to a modified structure (such as the sail-shaped secondaries of the drake mandarin duck) or distinctive colour (such as the speculum) on the bird.[41][42] Mallards of both sexes will lift a wing so that the brightly coloured speculum is showing, then will place their bill behind the speculum as if preening it.[43] Courtship preening is more conspicuous than is preening for feather maintenance, using more stereotypical movements.[44]

Preening may be performed as a

Allopreening

Although preening is primarily an individual behaviour, some species indulge in allopreening, one individual preening another.[14] It is not particularly common among birds, though species from at least 43 families are known to engage in the mutual activity.[49][50] Most allopreening activity concentrates on the head and neck, a lesser amount being directed towards the breast and mantle and an even smaller percentage applied to the flanks. A few species are known to allopreen other areas, including the rump, tail, belly and underwing.[51]

Several hypotheses have been advanced to explain the behaviour: that it assists in effective grooming, that it assists in recognition of individuals (mates or potential sexual partners), and that it assists in social communication, reducing or redirecting potential aggressive tendencies.[50] These functions are not mutually exclusive.[52] Evidence suggests that different species may participate for different reasons, and that those reasons may change depending on the season and the individuals involved.[50] In most cases, allopreening involves members of the same species, although some cases of interspecific allopreening are known; the vast majority of these involve icterids, though at least one instance of mutual grooming between a wild black vulture and a wild crested caracara has been documented.[53] Birds seeking allopreening adopt specific, ritualised postures to signal so; they may fluff their feathers out or put their heads down.[54] Captive birds of social species that normally live in flocks, such as parrots, will regularly solicit preening from their human owners.[55]

There is some evidence that allopreening may help to keep in good condition those feathers that a bird cannot easily reach by itself; allopreening activities tend to focus on the head and neck.

Most allopreening is done between the two members of a mated pair, and the activity appears to play an important role in strengthening and maintaining pair bonds.[14] It is more common in species where both parents help to raise the offspring and correlates with an increased likelihood that partners will remain together for successive breeding seasons.[48] Allopreening often features as part of the "greeting ceremony" between the members of a pair in species such as albatrosses and penguins, where partners may be separated for a relatively long period of time, and is far more common among sexually monomorphic species (that is, species where the sexes look outwardly similar). It appears to inhibit or redirect aggression, as it is typically the dominant bird that initiates the behaviour.[51]

Allopreening appears to reduce the incidence of conflict between members of some colonially living or colonially nesting species. Neighbouring

Potential problems

If birds are exposed to some pollutants, such as leaking petroleum, they can quickly lose the preen oil from their feathers. This causes a loss of heat regulation and waterproofing, and rapidly leads to the bird becoming chilled.[37] If waterbirds are exposed, they can lose both buoyancy and the ability to fly; this means they must swim constantly to stay warm and afloat (if they cannot reach land), and eventually die of exhaustion.[60] While preening in an effort to clean themselves, they may ingest harmfully large amounts of the petroleum.[37] Ingested oil can cause pneumonia, as well as liver and kidney damage. Studies done with black guillemots showed that even small amounts of ingested oil caused the birds physiological distress. It interfered with the foraging efficiency of adults and decreased the growth rates of young birds.[60]

Allopreening may facilitate disease transmission between infected and non-infected individuals.

References

- ^ "Preen". Oxford English Living Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on August 6, 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ Moon-Fandli, Dodman & O'Sullivan 1999, p. 68.

- ^ Luescher 2006, p. 198.

- S2CID 8499915.

- ^ Moss 2015, p. 71.

- ^ a b Lovette & Fitzpatrick 2016, p. 129.

- ^ Elphick & Dunning 2001, p. 58.

- ^ Elphick & Dunning 2001, p. 57.

- ^ Gill 2007, p. 104.

- ^ JSTOR 4535237.

- S2CID 17744188.

- JSTOR 1939301.

- ^ a b c Gill 2007, p. 102.

- ^ a b c d e f Campbell & Lack 1985, p. 102.

- ^ Montalti, Diego & Salibián, Alfredo (2000). "Uropygial gland size and avian habitat" (PDF). Ornitologia Neotropical. 11: 297–306.

- S2CID 9884724.

- S2CID 8342661.

- S2CID 4278863.

- S2CID 15209444.

- S2CID 21076057.

- PMID 27114098.

- ^ Perrins 2009, p. 37.

- ^ de Juana 1992, p. 40.

- JSTOR 1362391.

- ^ Ehrlich, Dobkin & Wheye 1988, p. 311.

- ^ Campbell & Lack 1985, pp. 102–103.

- .

- ^ a b Ehrlich, Dobkin & Wheye 1988, p. 543.

- ^ Hailman 1985, p. 214.

- S2CID 198156620.

- JSTOR 4081811.

- JSTOR 4082320.

- PMID 15888414.

- PMID 29866911.

- ^ Carnaby 2008, p. 358.

- ^ Ehrlich et al. 1994, p. 357.

- ^ a b c Kricher 2020, p. 118.

- ^ S2CID 29592388.

- ^ Ehrlich, Dobkin & Wheye 1988, p. 58.

- S2CID 38405658.

- S2CID 31957387.

- ^ Huxley, Hardy & Ford 1954, p. 242.

- ^ Ehrlich et al. 1994, p. 49.

- ^ Ehrlich et al. 1994, p. 37.

- JSTOR 4532768.

- JSTOR 4532894.

- PMID 5657176.

- ^ PMID 29622926.

- ^ Wilson 2000, p. 208.

- ^ JSTOR 4085549.

- ^ JSTOR 4533105.

- ^ S2CID 43724298.

- JSTOR 1367047.

- ^ a b Wilson 2000, p. 209.

- ^ Rowley 1997, p. 257.

- ^ Loon & Loon 2005, p. 36.

- ^ Olsen & Joseph 2011, p. 249.

- ^ Deeming & Reynolds 2015, p. 94.

- PMID 17550875.

- ^ a b Ehrlich et al. 1994, p. 225.

- PMID 15200828.

- PMID 20593026.

- S2CID 76664136.

- PMID 15252984.

- ^ Kubiak 2021, p. 175.

- ^ Coles 2007, p. 46.

Works cited

- Campbell, Bruce & Lack, Elizabeth, eds. (1985). A Dictionary of Birds. Carlton, UK: T and A D Poyser. ISBN 978-0-85661-039-4.

- Carnaby, Trevor (2008). Beat about the Bush: Birds. Johannesburg, South Africa: Jacana Media. ISBN 978-1-77009-241-9.

- Coles, Brian H., ed. (2007). Essentials of Avian Medicine and Surgery (3rd ed.). Oxford, UK: Blackwood Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-4051-5755-1.

- de Juana, Eduardo (1992). "Class Aves (Birds)". In del Hoyo, Josep; Elliott, Andrew & Sargatal, Jordi (eds.). ISBN 978-84-87334-10-8.

- Deeming, D. Charles & Reynolds, S. James, eds. (2015). Nests, Eggs, and Incubation: New ideas about avian reproduction. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-871866-6.

- Ehrlich, Paul R.; Dobkin, David S. & Wheye, Darryl (1988). The Birder's Handbook. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-62133-9.

- Ehrlich, Paul R.; Dobkin, David S.; Wheye, Darryl & Pimms, Stuart L. (1994). The Birdwatcher's Handbook. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-858407-0.

- Elphick, Chris & Dunning, John B. Jr. (2001). "Behaviour". In Elphick, Chris; Dunning, John B. Jr. & Sibley, David (eds.). The Sibley Guide to Bird Life & Behaviour. London: Christopher Helm. ISBN 978-0713662504.

- Gill, Frank B. (2007). Ornithology (3rd ed.). New York: Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-4983-7.

- Hailman, Jack P. (1985). "Behavior". In Pettingill, Olin Sewall (ed.). Ornithology in Laboratory and Field (5th ed.). Orlando, FL, US: Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-552455-1.

- Huxley, Julian; Hardy, A. C. & Ford, E. B., eds. (1954). Evolution as a Process. London: George Allan & Unwin. OCLC 1434718.

- Kricher, John (2020). Peterson Reference Guide to Bird Behavior. Boston, MA, US: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 978-1-328-78736-1.

- Kubiak, Marie, ed. (2021). Handbook of Exotic Pet Medicine. Hoboken, NJ, US: Wiley Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-119-38994-1.

- Loon, Rael & Loon, Hélène (2005). Birds: The Inside Story. Cape Town, South Africa: Struik. ISBN 978-1-77007-151-3.

- Lovette, Irby C. & Fitzpatrick, John W., eds. (2016). Handbook of Bird Biology (3rd ed.). Oxford, UK: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-29105-4.

- Luescher, Andrew U., ed. (2006). Manual of Parrot Behavior. Ames, IA, US: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8138-2749-0.

- Moon-Fandli, Alice M.; Dodman, Nicholas A. & O'Sullivan, Richard L. (1999). "Veterinary Models of Compulsive Self-grooming: Parallels with Trichotillamania". In Stein, Dan J.; Christenson, Gary A. & Hollander, Eric (eds.). Trichotillomania. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press. ISBN 978-0-88048-759-7.

- Moss, Stephen (2015). Understanding Bird Behaviour. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-4729-1206-0.

- Olsen, Penny & Joseph, Leo (2011). Stray Feathers: Reflections on the Structure, Behaviour and Evolution of Birds. Collingwood, VIC, Australia: CSIRO. ISBN 978-0-643-09493-2.

- Perrins, Christopher M. (2009). The Princeton Encyclopedia of Birds. Princeton, NJ, US: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-14070-4.

- Rowley, Ian (1997). "Family Cacatuidae (Cockatoos)". In del Hoyo, Josep; Elliott, Andrew; Sargatal, Jordi (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 4: Sandgrouse to Cuckoos. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions. ISBN 978-84-87334-22-1.

- Wilson, Edward O. (2000) [1975]. Sociobiology: The New Synthesis. Cambridge, MA, US: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-00089-6.

External links

- Barred owl preening on YouTube

- Splendid fairy-wrens preening and allopreening on YouTube