Pregabalin

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /priˈɡæbəlɪn/ |

| Trade names | Lyrica, others[1] |

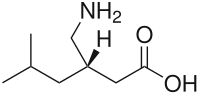

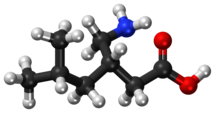

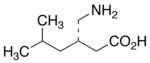

| Other names | 3-isobutyl GABA, (S)-3-isobutyl-γ-aminobutyric acid |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a605045 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category | |

GABA analog | |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Oral: High (≥90% rapidly absorbed; food has no significant effect on bioavailability)[11] |

| Protein binding | <1%[12] |

| Metabolites | N-methylpregabalin[11] |

| Onset of action | May occur within a week (pain)[13] |

| Elimination half-life | 4.5–7 hours[14] (mean 6.3 hours)[14][15] |

| Duration of action | Unknown[16] |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Pregabalin, sold under the brand name Lyrica among others, is an

Common side effects include headache,

Pregabalin was approved for medical use in the United States in 2004.

Medical uses

Seizures

For drug-resistant focal epilepsy, pregabalin is useful as an add-on therapy to other treatments.[35] Its use alone is less effective than some other seizure medications.[36] It is unclear how it compares to gabapentin for this use.[36]

Neuropathic pain

The European Federation of Neurological Societies recommends pregabalin as a first line agent for the treatment of pain associated with

Studies have shown that higher doses of pregabalin are associated with greater efficacy.[42]

Pregabalin's use in cancer-associated neuropathic pain is controversial,[43] though such use is common.[44] It has been examined for the prevention of post-surgical chronic pain, but its utility for this purpose is controversial.[45][46]

Pregabalin is generally not regarded as efficacious in the treatment of acute pain.[38] In trials examining the utility of pregabalin for the treatment of acute post-surgical pain, no effect on overall pain levels was observed, but people did require less morphine and had fewer opioid-related side effects.[45][47] Several possible mechanisms for pain improvement have been discussed.[48]

Anxiety disorders

Pregabalin is effective for treatment of generalized anxiety disorder.[49] It is also effective for the short- and long-term treatment of social anxiety disorder and in reducing preoperative anxiety.[50][51] However, there is concern regarding pregabalin's off-label use due to the lack of strong scientific evidence for its efficacy in multiple conditions and its proven side effects.[52]

The World Federation of Biological Psychiatry recommends pregabalin as one of several first line agents for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder, but recommends other agents such as

Generalized anxiety disorder

Pregabalin has

A 2019 review found that pregabalin reduces symptoms, and was generally well tolerated.[49]

Other uses

Although pregabalin is sometimes prescribed for people with bipolar disorder there is no evidence showing that it is effective.[51][59]

There is no evidence and significant risk in using pregabalin for sciatica and

There is no evidence for its use in the prevention of

Adverse effects

Exposure to pregabalin is associated with weight gain, sleepiness and fatigue, dizziness, vertigo, leg swelling, disturbed vision, loss of coordination, and euphoria.

- Very common (>10% of people with pregabalin): dizziness, drowsiness.

- Common (1–10% of people with pregabalin): blurred vision, asthenia, nasopharyngitis, increased creatine kinaselevel.

- Infrequent (0.1–1% of people with pregabalin): depression, lethargy, agitation, anorgasmia, hallucinations, kidney calculus

- Rare (<0.1% of people with pregabalin): neutropenia, first degree heart block, hypotension, hypertension, pancreatitis, dysphagia, oliguria, rhabdomyolysis, suicidal thoughts or behavior.[70]

Cases of recreational use, with associated adverse effects have been reported.[71]

Withdrawal symptoms

Following abrupt or rapid discontinuation of pregabalin, some people reported symptoms suggestive of

Pregnancy

It is unclear if it is safe for use in pregnancy with some studies showing potential harm.[73]

Breathing

In December 2019, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) warned about serious breathing issues for those taking gabapentin or pregabalin when used with CNS depressants or for those with lung problems.[74][75]

The FDA required new warnings about the risk of respiratory depression to be added to the prescribing information of the gabapentinoids.[74] The FDA also required the drug manufacturers to conduct clinical trials to further evaluate their abuse potential, particularly in combination with opioids, because misuse and abuse of these products together is increasing, and co-use may increase the risk of respiratory depression.[74]

Among 49 case reports submitted to the FDA over the five-year period from 2012 to 2017, twelve people died from respiratory depression with gabapentinoids, all of whom had at least one risk factor.[74]

The FDA reviewed the results of two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials in healthy people, three observational studies, and several studies in animals.[74] One trial showed that using pregabalin alone and using it with an opioid pain reliever can depress breathing function.[74] The other trial showed gabapentin alone increased pauses in breathing during sleep.[74] The three observational studies at one academic medical center showed a relationship between gabapentinoids given before surgery and respiratory depression occurring after different kinds of surgeries.[74] The FDA also reviewed several animal studies that showed pregabalin alone and pregabalin plus opioids can depress respiratory function.[74]

Overdose

An overdose of pregabalin usually consists of severe drowsiness, severe ataxia, blurred vision and macular detachment,[76] slurred speech, severe uncontrollable jerking motions (myoclonus), tonic clonic seizures and anxiety.[77] Despite these symptoms an overdose is not usually fatal unless mixed with another depressant. Several people with kidney failure developed myoclonus while receiving pregabalin, apparently as a result of gradual accumulation of the drug. Acute overdosage may be manifested by somnolence, tachycardia and hypertonia. Plasma, serum or blood concentrations of pregabalin may be measured to monitor therapy or to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized people.[78][79][80]

Pharmacology

Interactions

No interactions have been demonstrated

Pharmacodynamics

Pregabalin is a

The

Pregabalin was found to possess 6-fold higher affinity than gabapentin for α2δ subunit-containing VDCCs in one study.[91][92] However, another study found that pregabalin and gabapentin had similar affinities for the human recombinant α2δ-1 subunit (Ki = 32 nM and 40 nM, respectively).[93] In any case, pregabalin is 2 to 4 times more potent than gabapentin as an analgesic[84][94] and, in animals, appears to be 3 to 10 times more potent than gabapentin as an anticonvulsant.[84][94]

Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Pregabalin is

The

Distribution

Pregabalin crosses the blood–brain barrier and enters the central nervous system.[82] However, due to its low lipophilicity,[12] pregabalin requires active transport across the blood–brain barrier.[95][82][97][98] The LAT1 is highly expressed at the blood–brain barrier[99] and transports pregabalin across into the brain.[95][82][97][98] Pregabalin has been shown to cross the placenta in rats and is present in the milk of lactating rats.[11] In humans, the volume of distribution of an orally administered dose of pregabalin is approximately 0.56 L/kg.[11] Pregabalin is not significantly bound to plasma proteins (<1%).[12]

Metabolism

Pregabalin undergoes little or no

Pregabalin is generally safe in patients with liver cirrhosis.[101]

Elimination

Pregabalin is

Chemistry

Pregabalin is a

Synthesis

Chemical syntheses of pregabalin have been described.[105][106]

History

| External videos | |

|---|---|

| |

Pregabalin was synthesized in 1990 as an

Society and culture

Legal status

- United States: During clinical trials a small number of users (~4%) reported euphoria after use, which led to its control in the US.[114] The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) classified pregabalin as a depressant and placed pregabalin, including its salts, and all products containing pregabalin into Schedule V of the Controlled Substances Act.[115][66][116]

- Norway: Pregabalin is in prescription Schedule B, alongside benzodiazepines.[117][118]

- United Kingdom: On January 14, 2016, the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD) wrote a letter to Home Office ministers recommending that pregabalin alongside gabapentin should be controlled under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971.[119][120] It was announced in October 2018, that Pregabalin would become reclassified as a class C controlled substance from April 2019.[121][34][122]

In the United States, the FDA has approved pregabalin for

Economics

Pregabalin is available as a

Since 2008, Pfizer has engaged in extensive direct-to-consumer advertising campaigns to promote its branded product Lyrica for fibromyalgia and diabetic nerve pain indications. In January 2016, the company spent a record amount, $24.6 million for a single drug on TV ads, reaching global revenues of $14 billion, more than half in the United States.[127]

Up until 2009, Pfizer promoted Lyrica for other uses which had not been approved by medical regulators. For Lyrica and three other drugs, Pfizer was fined a record amount of US$2.3 billion by the Department of Justice,[128][129][130] after pleading guilty to advertising and branding "with the intent to defraud or mislead". Pfizer illegally promoted the drugs, with doctors "invited to consultant meetings, many in resort locations; attendees expenses were paid; they received a fee just for being there", according to prosecutor Michael Loucks.[128][129]

Intellectual property

Professor Richard "Rick" Silverman of Northwestern University developed pregabalin there. The university holds a patent on it, exclusively licensed to Pfizer.[131][132] That patent, along with others, was challenged by generic manufacturers and was upheld in 2014, giving Pfizer exclusivity for Lyrica in the US until 2018.[133][134]

Pfizer's main patent for Lyrica, for seizure disorders, in the UK expired in 2013. In November 2018, the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom ruled that Pfizer's second patent on the drug, for treatment of pain, was invalid because there was a lack of evidence for the conditions it covered – central and peripheral neuropathic pain. From October 2015, GPs were forced to change people from generic pregabalin to branded until the second patent ran out in July 2017. This cost the NHS £502 million.[135]

Brand names

As of October 2017, pregabalin was marketed under many brand names in other countries: Algerika, Alivax, Alyse, Alzain, Andogablin, Aprion, Averopreg, Axual, Balifibro, Brieka, Clasica, Convugabalin, Dapapalin, Dismedox, Dolgenal, Dolica, Dragonor, Ecubalin, Epica, Epiron, Gaba-P, Gabanext, Gabarol, Gabica, Gablin, Gablovac, Gabrika, Gavin, Gialtyn, Glonervya, Helimon, Hexgabalin, Irenypathic, Kabian, Kemirica, Kineptia, Lecaent, Lingabat, Linprel, Lyribastad, Lyric, Lyrica, Lyrineur, Lyrolin, Lyzalon, Martesia, Maxgalin, Mystika, Neuragabalin, Neugaba, Neurega, Neurica, Neuristan, Neurolin, Neurovan, Neurum, Newrica, Nuramed, Paden, Pagadin, Pagamax, Painica, Pevesca, PG, Plenica, Pragiola, Prebalin, Prebanal, Prebel, Prebictal, Prebien, Prefaxil, Pregaba, Pregabalin, Pregabalina, Pregabaline, Prégabaline, Pregabalinum, Pregabateg, Pregaben, Pregabid, Pregabin, Pregacent, Pregadel, Pregagamma, Pregalex, Pregalin, Pregalodos, Pregamid, Pregan, Preganerve, Pregastar, Pregatrend, Pregavalex, Pregdin Apex, Pregeb, Pregobin, Prejunate, Prelin, Preludyo, Prelyx, Premilin, Preneurolin, Prestat, Pretor, Priga, Provelyn, Regapen, Resenz, Rewisca, Serigabtin, Symra, Vronogabic, Xablin, and Xil.[136]

It was also marketed in several countries as a

References

- ^ "Pregabalin - Drugs.com". www.drugs.com. Archived from the original on August 28, 2019. Retrieved November 7, 2016.

- ^ "Avoid prescribing pregabalin in pregnancy if possible". Australian Government. Department of Health and Aged Care. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ "Product Information safety updates - January 2023". Australian Government. Department of Health and Aged Care. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ PMID 24760436.

- ^ "Prescription medicines: registration of new generic medicines and biosimilar medicines, 2017". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). June 21, 2022. Retrieved March 30, 2024.

- ^ Anvisa (March 31, 2023). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published April 4, 2023). Archived from the original on August 3, 2023. Retrieved August 16, 2023.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on December 4, 2023. Retrieved December 4, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Lyrica Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). February 27, 2023. Archived from the original on December 21, 2023. Retrieved December 21, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Lyrica- pregabalin capsule Lyrica- pregabalin solution". DailyMed. June 15, 2020. Archived from the original on September 25, 2021. Retrieved August 27, 2022.

- ^ "Lyrica EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). July 6, 2004. Archived from the original on December 21, 2023. Retrieved December 21, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Summary of product characteristics" (PDF). European Medicines Agency (EMA). March 6, 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 16, 2018. Retrieved May 6, 2013.

- ^ S2CID 9905501.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Pregabalin". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on December 2, 2019. Retrieved February 3, 2019.

- ^ a b Expert Committee on Drug Dependence Forty-first Meeting (November 2018). Critical Review Report: Pregabalin (PDF) (Report). Geneva: World Health Organization. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 26, 2020.

- from the original on August 3, 2022. Retrieved August 27, 2022 – via NCBI Bookshelf.

- ISBN 9780323358286.

- S2CID 5349255.

- S2CID 22262972.

- ^ ISBN 978-1-4511-5348-4.

- ISBN 978-1-118-76417-6.

- ISBN 978-1-58562-309-9. Archivedfrom the original on February 27, 2024. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- ^ S2CID 33200190.

- ^ PMID 21150315.

- PMID 25209095.

- ^ ISBN 9780857113382.

- ^ "Pregabalin Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on March 21, 2019. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ISBN 9781493919512. Archivedfrom the original on March 1, 2022. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- ^ a b "Generic Lyrica Availability". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ "FDA approves first generics of Lyrica". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). September 11, 2019. Archived from the original on June 9, 2020. Retrieved October 27, 2019.

- ^ "Pregabalin ER: FDA-Approved Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved June 19, 2021.

- ^ "Competitive Generic Therapy Approvals". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). June 29, 2023. Archived from the original on June 29, 2023. Retrieved June 29, 2023.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2021". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on January 15, 2024. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- ^ "Pregabalin - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on July 8, 2020. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- ^ a b "Pregabalin and gabapentin to be controlled as Class C drugs". GOV.UK. October 15, 2018. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- PMID 35349176.

- ^ PMID 23076957.

- S2CID 14236933.

- ^ PMID 30673120.

- S2CID 29830155.

- from the original on April 28, 2023. Retrieved April 28, 2023.

- PMID 36007534.

- (PDF) from the original on February 27, 2024. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- PMID 23915361.

- ISBN 978-0-85711-348-1.

- ^ S2CID 18933131.

- PMID 23881791.

- from the original on September 29, 2020. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- PMID 27069626.

- ^ S2CID 72332967. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 13, 2020. Retrieved September 8, 2020.; "Supplemental Appendices" (PDF). June 5, 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 9, 2020.; "Authors' Reply" (PDF). June 5, 2018. Archived from the original(PDF) on October 17, 2020.

- from the original on November 27, 2022. Retrieved October 27, 2022.

- ^ PMID 34819636.

- PMID 34819636.

- (PDF) from the original on April 3, 2018. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- S2CID 26320851.

- PMID 17940637.

- ^ "How long does it take for Lyrica to work?". Drugs.com. May 25, 2021. Archived from the original on February 18, 2022. Retrieved February 18, 2022.

- ^ S2CID 6229344.

- PMID 17940637.

- PMID 34577534.

- PMID 34637958.

- PMID 28809936.

- ^ Mannix L (December 18, 2018). "This popular drug is linked to addiction and suicide. Why do doctors keep prescribing it?". The Canberra Times. Archived from the original on December 18, 2018. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- PMID 27848217.

- PMID 23797675.

- PMID 30670513.

- ^ a b c "Schedules of Controlled Substances: Placement of Pregabalin Into Schedule V". Federal Register. July 28, 2005. Archived from the original on August 2, 2021. Retrieved August 27, 2022.

- S2CID 79760296.

- ^ Lyrica (Australian Approved Product Information), Pfizer Australia Pty Ltd., 2006, archived from the original on March 13, 2018

- ISBN 978-0-9757919-2-9.[page needed]

- ^ "Medication Guide (Pfizer Inc.)" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). June 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 8, 2011. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- S2CID 73986091.

- ^ "Lyrica Capsules". medicines.org.uk. Archived from the original on October 20, 2020. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ "Pregabalin Pregnancy and Breastfeeding Warnings". Archived from the original on March 21, 2019. Retrieved August 29, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "FDA warns about serious breathing problems with seizure and nerve pain medicines gabapentin (Neurontin, Gralise, Horizant) and pregabalin (Lyrica, Lyrica CR)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). December 19, 2019. Archived from the original on December 22, 2019. Retrieved December 21, 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "FDA warns about serious breathing problems with seizure and nerve pain medicines gabapentin (Neurontin, Gralise, Horizant) and pregabalin (Lyrica, Lyrica CR) When used with CNS depressants or in patients with lung problems" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). December 19, 2019. Archived from the original on December 22, 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- PMID 30405948.

- S2CID 53165515.

- S2CID 218857181.

- from the original on April 12, 2022. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ISBN 978-0-9626523-7-0.

- ^ "Pregabalin". Lexi-Drugs [database on the Internet. Hudson (OH): Lexi-Comp, Inc. 2007. Archived from the original on October 19, 2020. Retrieved October 29, 2015..

- ^ PMID 16376147.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-323-17080-2.

- ^ S2CID 38496241.

- ISBN 9781118075630. Archivedfrom the original on April 25, 2022. Retrieved August 17, 2016 – via Google Books.

- from the original on October 21, 2020. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- )

- ^ PMID 23642658.

- ^ PMID 17222465.

- ^ from the original on October 21, 2020. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- PMID 21897498.

- ISBN 9780702040597.

- from the original on October 23, 2020. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ S2CID 36137322.

- ^ from the original on October 21, 2020. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- PMID 18656534.

- ^ PMID 26305616.

- ^ S2CID 32513471.

- PMID 10518579.

- ISBN 978-0-8493-8259-8.

- S2CID 264888110.

- ^ PMID 18221197.

- S2CID 27431734.

- ISBN 978-1-60795-004-2.

- ISBN 978-0-12-411524-8. Archivedfrom the original on August 29, 2021. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- ISBN 978-1-118-62833-1. Archivedfrom the original on August 29, 2021. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- ^ Lowe D (March 25, 2008). "Getting to Lyrica". In the Pipeline. Science. Archived from the original on August 27, 2022. Retrieved November 21, 2015.

- ^ a b Merrill N (February 25, 2010). "Silverman's golden drug makes him NU's golden ticket". North by Northwestern. Archived from the original on June 1, 2016. Retrieved May 19, 2016.

- from the original on August 27, 2022. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

- ^ Poros J (2005). "Polish scientist is the co-author of a new anti-epileptic drug". Science and Scholarship in Poland. Archived from the original on August 20, 2016. Retrieved May 19, 2016.

- from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ "FDA approves LYRICA CR extended-release tablets CV". Seeking Alpha. October 12, 2017. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ^ "BRIEF-FDA approves Pfizer's Lyrica CR extended-release tablets CV". Reuters. Archived from the original on October 4, 2018. Retrieved October 3, 2018.

- ^ "Lyrica - FDA prescribing information, side effects and uses". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on August 13, 2017. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ "2005 - Placement of Pregabalin Into Schedule V". DEA Diversion Control Division. July 28, 2005. Archived from the original on May 28, 2022. Retrieved August 27, 2022.

- ^ "Title 21 CFR – PART 1308 – Section 1308.15 Schedule V". usdoj.gov. Archived from the original on September 3, 2020. Retrieved September 27, 2015.

- ^ "Lyrica". Felleskatalogen (in Norwegian). May 7, 2015. Archived from the original on December 23, 2016. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ "Re: Pregabalin and Gabapentin advice" (PDF). GOV.UK. January 14, 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- ^ "Pregabalin and gabapentin: proposal to schedule under the Misuse of Drugs Regulations 2001". GOV.UK. November 10, 2017. Archived from the original on January 3, 2020. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- from the original on August 9, 2019. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- ^ "Control of pregabalin and gabapentin under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971". GOV.UK. March 29, 2019. Archived from the original on February 21, 2024. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ "Pfizer to pay $2.3 billion to resolve criminal and civil health care liability relating to fraudulent marketing and the payment of kickbacks". Stop Medicare Fraud, U.S. Departments of Health & Human Services, and of Justice. Archived from the original on August 30, 2012. Retrieved July 4, 2012.

- ^ a b Levy S (July 22, 2019), "Nine generic firms get FDA approval for generic Lyrica.", Drug Store News, archived from the original on August 5, 2020

- ^ "Pfizer's Lyrica Approved for the Treatment of Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) in Europe" (Press release). Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- ^ "Generic Lyrica launches at 97% discount to brand version". 46brooklyn Research. July 23, 2019. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020. Retrieved December 25, 2019.

- ^ Bulik BS (March 2016). "AbbVie's Humira, Pfizer's Lyrica kick off 2016 with hefty TV ad spend". FiercePharma. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

- ^ New York Times. Archivedfrom the original on September 26, 2020. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- ^ a b "Pfizer agrees record fraud fine". BBC News. September 2, 2009. Archived from the original on September 8, 2009. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- ^ "Portions of the Pfizer Inc. 2010 Financial Report". U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. 2010. Archived from the original on June 10, 2019. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- from the original on October 26, 2020. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ US 6197819B1, Silverman RB, Andruszkiewicz R, "Gamma amino butyric acid analogs and optical isomers", issued March 6, 2001, assigned to Northwestern University Archived March 21, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Decker S (February 6, 2014). "Pfizer Wins Ruling to Block Generic Lyrica Until 2018". Bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on February 8, 2014. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ "Decision: Pfizer Inc. (PFE) v. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA Inc., 12-1576, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (Washington)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ "Pfizer's failed pregabalin patent appeal means NHS could reclaim £502m". Pulse. November 14, 2018. Archived from the original on November 15, 2018. Retrieved November 15, 2018.

- ^ a b "Pregabalin international brands". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on August 28, 2019. Retrieved October 27, 2017.