Prehistory

| Part of a series on |

| Human history and prehistory |

|---|

| ↑ before Homo (Pliocene epoch) |

| ↓ Future (Holocene epoch) |

Prehistory, also called pre-literary history,

In the early Bronze Age, Sumer in Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley Civilisation, and ancient Egypt were the first civilizations to develop their own scripts and keep historical records, with their neighbours following. Most other civilizations reached their end of prehistory during the following Iron Age. The three-age division of prehistory into Stone Age, Bronze Age, and Iron Age remains in use for much of Eurasia and North Africa, but is not generally used in those parts of the world where the working of hard metals arrived abruptly from contact with Eurasian cultures, such as Oceania, Australasia, much of Sub-Saharan Africa, and parts of the Americas. With some exceptions in pre-Columbian civilizations in the Americas, these areas did not develop complex writing systems before the arrival of Eurasians, so their prehistory reaches into relatively recent periods; for example, 1788 is usually taken as the end of the prehistory of Australia.

The period when a culture is written about by others, but has not developed its own writing system is often known as the protohistory of the culture. By definition,[2] there are no written records from human prehistory, which can only be known from material archaeological and anthropological evidence: prehistoric materials and human remains. These were at first understood by the collection of folklore and by analogy with pre-literate societies observed in modern times. The key step to understanding prehistoric evidence is dating, and reliable dating techniques have developed steadily since the nineteenth century.[3] Further evidence has come from the reconstruction of ancient spoken languages. More recent techniques include forensic chemical analysis to reveal the use and provenance of materials, and genetic analysis of bones to determine kinship and physical characteristics of prehistoric peoples.

Definition

Beginning and end

The beginning of prehistory is normally taken to be marked by human-like beings appearing on Earth.

Both dates consequently vary widely from region to region. For example, in

Time periods

In dividing up human prehistory in Eurasia, historians typically use the three-age system, whereas scholars of pre-human time periods typically use the

For the prehistory of the Americas see Pre-Columbian era.

History of the term

The notion of "prehistory" emerged during the Enlightenment in the work of antiquarians who used the word "primitive" to describe societies that existed before written records.[14] The word "prehistory" first appeared in English in 1836 in the Foreign Quarterly Review.[15]

The geologic time scale for pre-human time periods, and the three-age system for human prehistory, were systematized during the late nineteenth century in the work of British, German, and Scandinavian anthropologists, archeologists, and antiquarians.[12]

Means of research

The main source of information for prehistory is archaeology (a branch of anthropology), but some scholars are beginning to make more use of evidence from the natural and social sciences.[16][17][18]

The primary researchers into human prehistory are archaeologists and

Human prehistory differs from history not only in terms of its chronology, but in the way it deals with the activities of archaeological cultures rather than named nations or individuals. Restricted to material processes, remains, and artefacts rather than written records, prehistory is anonymous. Because of this, reference terms that prehistorians use, such as "Neanderthal" or "Iron Age", are modern labels with definitions sometimes subject to debate.

Stone Age

The concept of a "Stone Age" is found useful in the archaeology of most of the world, although in the archaeology of the Americas it is called by different names and begins with a Lithic stage, or sometimes Paleo-Indian. The sub-divisions described below are used for Eurasia, and not consistently across the whole area.

Palaeolithic

"Palaeolithic" means "Old Stone Age", and begins with the first use of stone tools. The Paleolithic is the earliest period of the Stone Age. It extends from the earliest known use of stone tools by hominins c. 3.3 million years ago, to the end of the Pleistocene c. 11,650 BP (before the present period).[19]

The early part of the Palaeolithic is called the

The Upper Paleolithic extends from 50,000 and 12,000 years ago, with the first organized settlements and blossoming of artistic work.

Throughout the Palaeolithic, humans generally lived as

Mesolithic

The Mesolithic, or Middle Stone Age (from the Greek mesos, 'middle', and lithos, 'stone'), was a period in the development of human technology between the Palaeolithic and Neolithic.

The Mesolithic period began with the retreat of glaciers at the end of the

Regions that experienced greater environmental effects as the

Remains from this period are few and far between, often limited to middens. In forested areas, the first signs of deforestation have been found, although this would only begin in earnest during the Neolithic, when more space was needed for agriculture.

The Mesolithic is characterized in most areas by small composite

Neolithic

"Neolithic" means "New Stone Age", from about 10,200 BCE in some parts of the Middle East, but later in other parts of the world,

Early Neolithic farming was limited to a narrow range of plants, both wild and domesticated, which included

Settlements became more permanent, some with circular houses made of

Chalcolithic

In Old World archaeology, the "Chalcolithic", "Eneolithic", or "Copper Age" refers to a transitional period where early copper metallurgy appeared alongside the widespread use of stone tools. During this period, some weapons and tools were made of copper. This period was still largely Neolithic in character. It is a phase of the Bronze Age before it was discovered that adding tin to copper formed the harder bronze. The Copper Age is seen as a transition period between the Stone Age and Bronze Age.[43]

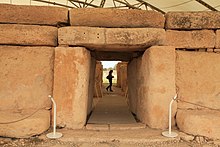

An archaeological site in

Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is the earliest period in which some civilizations reached the end of prehistory, by introducing written records. The Bronze Age, or parts thereof, are thus considered to be part of prehistory only for the regions and civilizations who developed a system of keeping written records during later periods. The invention of writing coincides in some areas with the beginnings of the Bronze Age. After the appearance of writing, people started creating texts including written records of administrative matters.[46]

The Bronze Age refers to a period in human cultural development when the most advanced

While copper is a common ore, deposits of tin are rare in the

By the end of the Bronze Age large states, whose armies imposed themselves on people with a different culture, and are often called empires, had arisen in Egypt, China, Anatolia (the Hittites), and Mesopotamia, all of them literate.

Iron Age

The Iron Age is not part of prehistory for all civilizations who had introduced written records during the Bronze Age. Most remaining civilizations did so during the Iron Age, often through conquest by empires, which continued to expand during this period. For example, in most of Europe conquest by the

In archaeology, the Iron Age refers to the advent of ferrous metallurgy. The adoption of iron coincided with other changes, often including more sophisticated agricultural practices, religious beliefs and artistic styles, which makes the archaeological Iron Age coincide with the "Axial Age" in the history of philosophy. Although iron ore is common, the metalworking techniques necessary to use iron are different from those needed for the metal used earlier, more heat is required.[48] Once the technical challenge had been solved, iron replaced bronze as its higher abundance meant armies could be armed much more easily with iron weapons.[49]

Timeline

million years ago ) |

All dates are approximate and conjectural, obtained through research in the fields of

Paleolithic

- c. 3.3 million BP – Earliest stone tools[20]

- c. 2.8 million BP – Genus Homo appears

- c. 600,000 BP – Hunting-gathering

- c. 400,000 BP – Control of fire by early humans

- c. 300,000 BP – Homo sapiens sapiens) appear in Africa,[24] one of whose characteristics is a lack of significant body hair compared to other primates. See Jebel Irhoud.

- c. 300,000–30,000 BP – Mousterian (Neanderthal) culture in Europe.[50]

- c. 170,000–83,000 BP – Invention of clothing[51]

- c. 75,000 BP – Toba Volcano supereruption.[52]

- c. 80,000–50,000 BP –

- c. 80,000–50,000? BP – Behavioral modernity, by this point including language and sophisticated cognition

- c. 45,000 BP / 43,000 BCE – Beginnings of Châtelperronian culture in France.

- c. 40,000 BP / 38,000 BCE – First human settlement in the )

- c. 32,000 BP / 30,000 BCE – Beginnings of parietal art") of Chauvet Cavein France.

- c. 30,500 BP / 28,500 BCE – New Guinea is populated by colonists from Asia or Australia.[59]

- c. 30,000 BP / 28,000 BCE – A herd of reindeer is slaughtered and butchered by humans in the Vezere Valley in what is today France.[60]

- c. 28,000–20,000 BP – Gravettian period in Europe. Harpoons, needles, and saws invented.

- c. 26,500 BP – Settlement of the Americas).

- c. 26,000 BP / 24,000 BCE – People around the world use fibres to make baby-carriers, clothes, bags, baskets, and nets.[61]

Overview map of the peopling of Eurasia and Australia by anatomically modern humans - c. 25,000 BP / 23,000 BCE – A settlement consisting of huts built of rocks and mammoth bones is founded near what is now Dolní Věstonice in Moravia in the Czech Republic. This is the oldest human permanent settlement that has been found by archaeologists.[62]

- c. 23,000 BP / 21,000 BCE – Small-scale trial cultivation of plants in Ohalo II, a hunter-gatherers' sedentary camp on the shore of the Sea of Galilee, Israel.[63]

- c. 16,000 BP / 14,000 BCE – Wisent (bison) sculpted in clay deep inside the cave now known as Le Tuc d'Audoubert in the French Pyrenees near what is now the border of Spain.[64]

- c. 14,800 BP / 12,800 BCE – The Humid Period begins in North Africa. The region that would later become the Sahara is wet and fertile, and the aquifers are full.[65]

Epipaleolithic

- c. 12,500 to 9,500 BCE – Natufian culture: a culture of sedentary hunter-gatherers who may have cultivated rye in the Levant (Eastern Mediterranean)

Neolithic

- c. 9,400–9,200 BCE –

- c. 9,000 BCE – Circles of T-shaped stone pillars erected at pre-pottery Neolithic A(PPNA) period. As yet unexcavated structures at the site are thought to date back to the epipaleolithic.

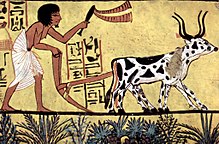

- c. 8,000 BC / 7000 BCE – In northern Mesopotamia, now northern Iraq, cultivation of barley and wheat begins. At first they are used for beer, gruel, and soup, eventually for bread.[69] In early agriculture at this time the planting stick is used, but it is replaced by a primitive plough in subsequent centuries.[70] Around this time, a round stone tower, now preserved at about 8.5 meters high and 8.5 meters in diameter is built in Jericho.[71]

Chalcolithic

- c. 3,700 BCE – Pictographic proto-writing, known as proto-cuneiform, appears in Sumer, and records begin to be kept. According to the majority of specialists, the first Mesopotamian writing (actually still pictographic proto-writing at this stage) was a tool for record-keeping that had little connection to the spoken language.[72]

- c. 3,300 BCE – Approximate date of death of "Ötzi the Iceman", found preserved in ice in the Ötztal Alps in 1991. A copper-bladed axe, which is a characteristic technology of this era, was found with the corpse.

- c. 3,100 BCE – Skara Brae is constructed. This stone-built village consisted of ten clustered houses with stone hearths, beds, cupboards, and an ancient sewer system. This village occupied for 600 years before being abandoned in c. 2,500 BCE.

- c. 3,000 BCE – Stonehenge construction begins. In its first version, it consisted of a circular ditch and bank, with 56 wooden posts.[73]

- c. 3,000 BCE – The Yamnaya expansions from the Pontic–Caspian steppe into Europe and Asia. These migrations are thought to have spread Yamnaya Steppe pastoralist ancestry and Indo-European languages across large parts of Eurasia.[74]

By region

- Old World

- Prehistoric Africa

- Predynastic Egypt

- Prehistoric Central North Africa

- Prehistoric Asia

- East Asia:

- Prehistoric China

- Prehistoric Korea

- Japanese Paleolithic

- East Asian Bronze Age

- Chinese Bronze Age

- South Asia

- Prehistory of India

- South Asian Stone Age

- Prehistory of Sri Lanka

- Prehistory of Central Asia

- Prehistoric Siberia

- Southeast Asia:

- Southwest Asia (Near East)

- East Asia:

- Prehistoric Europe

- Prehistoric Caucasus

- Paleolithic Europe

- Neolithic Europe

- Bronze Age Europe

- Iron Age Europe

- Atlantic fringe

- Prehistoric Balkans

- New World

- Pre-Columbian Americas

- Prehistoric Southwestern cultural divisions

- 2nd millennium BCE in North American prehistory

- 1st millennium BCE in North American prehistory

- 1st millennium in North American prehistory

- Prehistory of Newfoundland and Labrador

- Prehistory of the Canadian Maritimes

- Prehistory of Quebec

- Oceania

- Prehistoric Australia

See also

References

- JSTOR 202691.

- ^ "Dictionary Entry". Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- ^ Graslund, Bo. 1987. The birth of prehistoric chronology. Cambridge:Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b c Renfrew, Colin. 2008. Prehistory: The Making of the Human Mind. New York: Modern Library

- ^ a b Fagan, Brian. (2007). World Prehistory: A brief introduction New York: Prentice-Hall, (Seventh ed.), Chapter One

- OCLC 958480847.

- OCLC 70728478.

- OCLC 1120111673.

- S2CID 161120240.

- ^ a b "Viewing the Ancient Celts through the Lens of Greece and Rome". GHD. February 9, 2021.

- ^ Huntsman, Authors: Theresa. "Etruscan Language and Inscriptions | Essay | The Metropolitan Museum of Art | Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History". The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History.

- ^ a b Matthew Daniel Eddy, ed. (2011). Prehistoric Minds: Human Origins as a Cultural Artefact. Royal Society of London. Archived from the original on 2021-04-01. Retrieved 2014-09-19.

- ^ "Chalcolithic | British Museum". Archived from the original on 6 March 2023. Retrieved 6 March 2023.

- from the original on 2021-04-01. Retrieved 2014-02-02.

- from the original on 2021-04-01. Retrieved 2014-02-02.

- ^ The Prehistory of Iberia: Debating Early Social Stratification and the State edited by María Cruz Berrocal, Leonardo García Sanjuán, Antonio Gilman. Pg 36.

- ^ Historical Archaeology: Back from the Edge. Edited by Pedro Paulo A. Funari, Martin Hall, Sian Jones. p. 8.ISBN 9780415518888

- ^ Through the Ages in Palestinian Archaeology: An Introductory Handbook. By Walter E. Ras. p. 49.ISBN 9781563380556

- ISBN 978-3-540-32474-4.

- ^ from the original on 2021-10-09. Retrieved 2022-05-31.

- ^ Harmand et al., 2015, p. 315.

- ^ "How Early Humans Shaped the World With Fire". SAPIENS. May 28, 2021.

- ^ Magazine, Smithsonian. "Fire Good. Make Human Inspiration Happen". Smithsonian Magazine.

- ^ (PDF) from the original on 8 January 2020. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- ^ Race and Human Evolution. By Milford H. Wolpoff. p. 348.

- S2CID 146473957. Archived from the original(PDF) on 12 December 2015. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- ^ Vanishing Voices : The Extinction of the World's Languages. By Daniel Nettle, Suzanne Romaine Merton Professor of English Language University of Oxford. pp. 102–103.

- S2CID 145014800.

- ^ "Songlines: the Indigenous memory code". Radio National. 2016-07-08. Archived from the original on 2018-12-21. Retrieved 2019-02-18.

- ^ "Epipalaeolithic". glosbe.com.

- ^ "Hagarqim « Heritage Malta". Archived from the original on 2009-02-03. Retrieved 2009-02-20.

- ^ First Farmers: The Origins of Agricultural Societies by Peter Bellwood, 2004

- ^ "World Museum of Man: Neolithic / Chalcolithic Period". World Museum of Man. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- ^ "Stone Age - Prehistoric Americas, Tools, Artifacts | Britannica".

- S2CID 162580508.

- ^ Winn, Shan (1981). Pre-writing in Southeastern Europe: The Sign System of the Vinča Culture ca. 4000 BC. Calgary: Western Publishers.

- ISBN 978-0-7190-5612-3. Archivedfrom the original on 2021-04-01. Retrieved 2020-08-22.

- ^ Harris, Susanna (2009). "Smooth and Cool, or Warm and Soft: Investigatingthe Properties of Cloth in Prehistory". North European Symposium for Archaeological Textiles X. Academia.edu. Archived from the original on 1 April 2021. Retrieved 5 September 2013.

- ^ "Aspects of Life During the Neolithic Period" (PDF). Teachers' Curriculum Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 May 2016. Retrieved 5 September 2013.

- ^ Gibbs, Kevin T. (2006). "Pierced clay disks and Late Neolithic textile production". Proceedings of the 5th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East. Academia.org. Archived from the original on 1 April 2021. Retrieved 5 September 2013.

- ^ Green, Jean M (1993). "Unraveling the Enigma of the Bi: The Spindle Whorl as the Model of the Ritual Disk". Asian Perspectives. 32 (1): 105–124. Archived from the original on 2015-02-11.

- ^ Cook, M (2007). "The clay loom weight, in: Early Neolithic ritual activity, Bronze Age occupation and medieval activity at Pitlethie Road, Leuchars, Fife". Tayside and Fife Archaeological Journal. 13: 1–23.

- ^ Sasha Blakeley; Christopher Muscato (2023). "Copper Age / Chalcolithic Age". Study.com.

- ^ "Serbian site may have hosted first copper makers". ScienceNews. July 17, 2010. Archived from the original on May 8, 2013. Retrieved October 28, 2015.

- ^ "Timna". Biblical Archaeology – Maps and Findings.

- ^ "The University of Chicago Magazine: Features". magazine.uchicago.edu.

- ^ "Three-age system | archaeology | Britannica". www.britannica.com.

- ^ "Bronze and Iron: A Comparison · Extended Artefact Features · Museum of Classical Antiquities, University of Ottawa". omeka.uottawa.ca.

- ^ "Why Did it Take So Long Between the Bronze Age and the Iron Age? | MATSE 81: Materials In Today's World". www.e-education.psu.edu.

- S2CID 86608040.

- from the original on 2017-01-14.

- ^ Jones, Tim (July 6, 2007). "Mount Toba Eruption – Ancient Humans Unscathed, Study Claims". Anthropology.net. Archived from the original on 2018-07-08. Retrieved 2008-04-20.

- New York Times. Archivedfrom the original on May 2, 2019. Retrieved September 22, 2016.

- ^ a b This is indicated by the M130 marker in the Y chromosome. "Traces of a Distant Past", by Gary Stix, Scientific American, July 2008, pp. 56–63.

- ^ Macey, Richard (2007). "Settlers' history rewritten: go back 30,000 years". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ^ "Aboriginal people and place". Sydney Barani. 2013. Archived from the original on 8 February 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ^ Sandra Bowdler. "The Pleistocene Pacific". Published in 'Human settlement', in D. Denoon (ed) The Cambridge History of the Pacific Islanders. pp. 41–50. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. University of Western Australia. Archived from the original on 16 February 2008. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- Keilor, about 40,000 years ago."

- ISBN 978-0-8050-3134-8

- ^ Gene S. Stuart, "Ice Age Hunters: Artists in Hidden Cages." In Mysteries of the Ancient World, a publication of the National Geographic Society, 1979. pp. 11–18.

- ^ "Venus of Willendorf". Khan Academy. Archived from the original on 2019-02-03. Retrieved 2019-02-18.

- ^ Stuart, Gene S. (1979). "Ice Age Hunters: Artists in Hidden Cages". Mysteries of the Ancient World. National Geographic Society. p. 19.

- PMID 26200895.

- ^ Stuart, Gene S. (1979). "Ice Age Hunters: Artists in Hidden Cages". Mysteries of the Ancient World. National Geographic Society. pp. 8–10.

- New York Times, May 9, 2008.

- S2CID 42150441.

- PMID 17170278.

- PMID 17170278.

- ^ Kiple, Kenneth F. and Ornelas, Kriemhild Coneè, eds., The Cambridge World History of Food, Cambridge University Press, 2000, p. 83

- ^ "No-Till: The Quiet Revolution", by David Huggins and John Reganold, Scientific American, July 2008, pp. 70–77.

- ISBN 978-0-521-40216-3, p. 363.

- ^ Glassner, Jean-Jacques. The Invention of Cuneiform: Writing In Sumer. Trans.Zainab, Bahrani. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003. Ebook.

- ^ Caroline Alexander, "Stonehenge", National Geographic, June 2008.

- ^ Curry, Andrew (August 2019). "The first Europeans weren't who you might think". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 2023-03-06. Retrieved 2022-10-28.

External links

- Submerged Landscapes Archaeological Network

- North Pacific Prehistory is an academic journal specialising in Northeast Asian and North American archaeology.

- Prehistory in Algeria and in Morocco

- Early Humans a collection of resources for students from the Courtenay Middle School Library.