Prehistory of France

| History of France |

|---|

|

| Topics |

| Timeline |

|

|

Prehistoric France is the period in the human occupation (including early hominins) of the geographical area covered by present-day France which extended through prehistory and ended in the Iron Age with the Roman conquest, when the territory enters the domain of written history.

The

The first trace of human occupation in France is dated to more than 1.57 million years ago. The earliest known fossil man is

In the Neolithic , which begins in the south of France in the middle of the 6th millennium BC, the first farmers appeared. The first megaliths were erected in the early 5th millennium BC.

The Palaeolithic

Lower Palaeolithic

The lower paleolithic period began with the first human occupation of the region. Stone tools discovered at Lézignan-la-Cèbe indicate that early humans were present in France from least 1.57 million years ago.[3]

5 prehistoric sites in France are dated from between 1 and 1.2 million years ago:[4]

- the Bois-de-Riquet , in Lézignan-la-Cèbe , in the Hérault (1.2 Ma), discovered in 2008

- the Vallonnet cave , in Roquebrune-Cap-Martin , in the Alpes-Maritimes (1.15 Ma), discovered in 1958

- Terre-des-Sablons, in Lunery-Rosières , in Cher (1.15 Ma),

- Pont-de-Lavaud, at Éguzon-Chantôme , in Indre (1.05 Ma),

- Pont-de-la-Hulauderie, in Saint-Hilaire-la-Gravelle , in Loir-et-Cher (1 My).

None of these sites have thus far revealed any evidence of lithic industry which prevents identification of the human species responsible for them.[4]

France includes

The

Middle Palaeolithic

The

Important Mousterian sites are found at:

- Fieux, in Lot-et-Garonne (340 ka) [8]

- Petit-Bost, in the Dordogne (325 ka)[9]

The first identified Neanderthal burials were discovered at La Chapelle-aux-Saints in 1908 (dating from 70 ka) then at La Ferrassie in 1909.[10] The identification of burial practices in Neanderthals at these sites led to new insights concerning the capacity of Neanderthals to develop spiritual or metaphysical beliefs,[11] extending understanding of the human species beyond what had been hitherto assumed.[12]

Upper Palaeolithic

The earliest indication of

European Palaeolithic cultures are divided into several chronological subgroups (the names are all based on French type sites, principally in the Dordogne region):[15]

- Venus figurines, cave paintings at the Chauvet Cave(continued during the Gravettian period).

- Périgordian (c. 35,000 - 20,000 BP) – use of this term is being debated (the term implies that the following subperiods represent a continuous tradition).

- Châtelperronian (c. 39,000 - 29,000 BP) – culture derived from the earlier, Neanderthal, Mousterian industry as it made use of Levallois cores and represents the period when Neanderthals and modern humans occupied Europe together.

- Venus figurines, cave paintings at the Cosquer Cave.

- Solutrean (c. 22,000 - 17,000 BP)

- Trois-Frères cave and the Rouffignac Cave also known as The Cave of the hundred mammoths. It possesses the most extensive cave system of the Périgordin France with more than 8 kilometers of underground passageways.

-

Chauvet cave painting, Aurignacian culture

-

Venus of Brassempouy, Gravettian culture

-

Inscribed bones, Gravettian culture

-

Lascaux cave painting, Magdalenian culture

-

Lascaux cave painting, Magdalenian culture

-

Stone engraving, Magdalenian culture

-

Bone sculpture, Magdalenian culture

-

Large biface, Solutrean culture

The Mesolithic

From the Paleolithic to the Mesolithic, the Magdalenian culture evolved. The Early Mesolithic, or Azilian, began about 14,000 years ago, in the Franco-Cantabrian region of northern Spain and Southern France. This was ahead of other parts of Western Europe, where the Mesolithic began by 11,500 years ago at the beginning of the Holocene. It ended with the introduction of farming.[17]

The Azilian culture of the

Archeologists are unsure whether Western Europe saw a Mesolithic immigration. Populations speaking non-Indo-European languages are obvious candidates for Mesolithic remnants. The

The Neolithic

The

Many European Neolithic groups share basic characteristics, such as living in small-scale family-based communities, subsisting on

The 'Armorican' (

It is most likely from the Neolithic that date the

-

Le Menec alignments, Carnac.

-

Cairn of Barnenez, Brittany, c. 4800 BC

-

Turquoise necklace, Carnac, 4500 BC

-

Polished jade axes, Carnac, c. 4500 BC

-

Polished jade rings, Carnac, c. 4500 BC

-

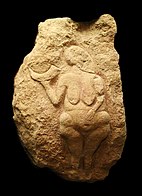

Stele, Chasséen culture, 4th millennium BC.[b]

-

Linear Pottery culture longhouse, c. 5000 BC

-

Ceramics from Fontbouisse, c. 3000 BC

-

Gold diadem, jade axe and boar's tusk pectoral, Pauilhac, c. 3500 BC

-

Locmariaquer megaliths, c. 4500 BC

-

Champ Durand fortifications, c. 3400 BC

-

Tumulus of Bougon, c. 4700 BC

-

Table des Marchand, c. 4000 BC

-

Dolmen de Bagneux, c. 4000-3000 BC

The Copper Age

During the Chalcolithic or Copper Age, a transitional age from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age, France shows evidence of the Seine-Oise-Marne culture and the Beaker culture.

The

Beginning about 2600 BC, the

The Bell Beaker culture (c. 2800–1900 BC) was a widespread phenomenon that expanded over most of France, excluding the Massif Central, in the third and early second millennia BC.[citation needed]

-

Remains of a large building at Challignac, Artenacian culture

-

Copper axe, Brittany, 3rd millennium BC

-

Bell Beaker, c. 2500 BC

-

Flint arrowheads, Bell Beaker culture

-

Copper daggers, Bell Beaker culture

-

Gold lunulas, Brittany, Bell Beaker culture

-

Illustration of a Bell Beaker wagon

-

The Bell Beaker culture had domesticated horses.[28]

The Bronze Age

In the

In France, the first studies on the Bronze Age date from the 19th century. The "Manuel d'archéologie préhistorique, celtique et gallo-romaine," (Manual of Prehistoric, Celtic and Gallo-Roman Archaeology), by Joseph Déchelette, published in 1910, was for a long time the reference for the study of this period.[29] In the 1950s, Jean-Jacques Hatt proposed a subdivision of the French Bronze Age, and in 1958 he published a tripartate division.[30] This model divided the Bronze Age into three parts, Early Bronze, Middle Bronze and Late Bronze Age and serves as a reference for the majority of subsequent studies on the Bronze Age in France.[31]

The

Some archeologists date the arrival of several non-Indo-European peoples to this period, including the

-

Bronze dagger, Rhône culture, c. 2000 BC

-

Tumulus culture ceramics

-

Gold vessels, Tumulus culture, c. 1400 BC

-

Bronze cuirasses, Urnfield culture, 900 BC

-

Bronze helmets, Urnfield culture, 1100-900 BC

-

Urnfield culture artefacts

-

Model of a fortification wall, Urnfield culture

-

Fort Harrouard hillfort, Middle-Late Bronze Age

-

Bronze vessels, Urnfield culture, c. 1000 BC

-

Bronze pins and ornaments, Urnfield culture, c. 1000 BC

-

Urnfield culture warrior, reconstruction

-

Atlantic Bronze Age, gold belt, 1300-1150 BC

-

Plougrescant sword, Atlantic Bronze Age, c. 1300 BC

The Iron Age

The spread of

The Hallstatt culture was succeeded by the

In addition,

By the 2nd century BC, Celtic France was called

-

Vix palace, Hallstatt culture, 500 BC

-

Vix grave, wagon burial reconstruction, Hallstatt culture, 500 BC

-

Cult wagon, Hallstatt culture, 750 BC

-

Swords, La Tène culture

-

Painted pottery, La Tène culture

-

Chariot mounts from Somme-Bionne, La Tène culture

-

Basse Yutz flagons, La Tène culture, 450 BC

-

Chariot fitting, La Tène culture

-

Chariot burial, La Tène culture

-

Bibracte oppidum, outer walls, La Tène culture

-

Gallic farm at Verberie, La Tène culture

-

Murus Gallicus, c. 100 BC, La Tène culture

-

Corent oppidum, La Tène culture

-

Settlement at Arles, c. 2nd century BC

-

Statue from Roquepertuse, 3rd-2nd century BC

Timeline

Prehistoric and Iron Age France - all dates are BC

- 1,800,000 (Date not considered secure) : Appearance of stone tools (possibly by Homo erectus) in France (Chilhac, Haute-Loire).[38]

- 1,570,000: Stone tools at Lézignan-la-Cèbe.[3]

- 1,050,000 to 1,000,000: stone tools at Grotte du Vallonnet, near Menton.[5]

- 900,000: Beginning of Günz glaciation.[39]

- 700,000: Oldest shaped tools in Brittany.

- 600,000: Beginning of Günz-Mindel interglacial.[39] Appearance of Homo heidelbergensis in Europe.

- 450,000: "Tautavel man" (possibly Homo heidelbergensis).

- 410,000: Beginning of .

- 400,000: Mindel II. Shards of "proto-Levallois" tools.

- 400,000 to 380,000: Traces of first domestication of fire at Terra Amata (Nice).

- 300,000: Beginning of Mindel-Riss interglacial.[39]

- 300,000: Appearance of Neanderthals in Europe.[6]

- 200,000: Beginning of Riss glaciation.[39]

- 130,000: Beginning of Riss-Würm interglacial.[39]

- 70,000: Beginning of Würm glaciation.[39]

- 62,000: Würm I/II interglacial.[39]

- 57,000: Brorup interglacial.[39]

- 55,000: Würm II.[39]

- 40,000: Laufen interglacial.[39] Arrival of first modern humans (Cro-Magnons) in Europe.

- 35,000: Würm IIIa.[39] Châtelperronian culture.

- 33,000: Mask of la Roche-Cotard, a Mousterian artefact.

- 32,000: Aurignacian culture.[15]

- 30,000: First statuettes and engravings in France. Disappearance of Neanderthals.

- 28,000: Arcy interglacial.[citation needed]

- 27,500: Würm IIIb.[39]

- 25,000: Paudorf interglacial.

- 23,000: Würm IIIc.[39]

- 18,000: End of Würm glaciation.[39]

- 18,692: Beginning of Solutrean culture.

- 16,000: Cold spell (Oldest Dryas).

- 15,000: Magdalenian culture.[18]

- 15,300: Lascaux.[18]

- 14,500: Middle Magdalenian. Bølling Oscillation.[18]

- 14,100: Cold spell (Older Dryas).

- 14,000: Allerød Oscillation.

- 13,500: Upper Magdalenian.[18]

- 13,000: Hamburg culture[18]

- 10,300: Cold spell (Younger Dryas).

- 9500: Beginning of Holocene.

- 7000: Domestication of the sheep.

- 6900: Domestication of the dog.

- 5000: Appearance of Linear Pottery culture in France.[citation needed]

- 4650: Oldest neolithic village in France, Courthézon in the Vaucluse.[citation needed]

- 4000: Neolithic Chasséen culture village of Bercy.[citation needed]

- 3610: Appearance of first megaliths in France.[24]

- 3430: Chasséen culture village of Saint-Michel du Touch near Toulouse.[citation needed]

- 3430: Appearance of Rössen culture at Baume de Gonvilla in Haute-Saône.[citation needed]

- 3250: Expansion of Chasséen culture in the south of France, from the Lot to the Vaucluse.[citation needed]

- 3190: Chasséen culture in Calvados.[citation needed]

- 2530: Chasséen culture in Pas-de-Calais.[citation needed]

- 2450: End of Chasséen culture in Eure-et-Loir.[citation needed]

- 2400: End of Chasséen culture in Saint-Mitre (in Reillanne, Alpes-de-Haute-Provence).[citation needed]

- 2300: Village at Beaker culture.[citation needed]

- 1800: Beginning of Bronze Age in France.[29]

- 800: Appearance in France, via the Bourgogne of the Urnfield culture.[35]

- 725: Beginning of Hallstatt culture.[35]

- 680: Founding of Antibes, the first Greek colony in France.[37]

- 600: Founding of Massalia (future Marseille) by the Greeks from the Ionian city of Phocaea.[37]

- 450: The

- 390: The

- 121: Roman occupation of Gallia Narbonensis.[37]

- 118: Founding of the Roman colony Narbo Martius (future Narbonne).[37]

- 58-51: Conquest of Gaul by Julius Caesar.[37]

See also

- Timeline of glaciation

- Neolithic Europe

- Old European culture

- Proto-Indo-Europeans

- Proto-Celtic language

- Prehistory of Brittany

- Prehistoric Britain

- Prehistoric Iberia

- Prehistoric Romania

- Archaeological sites in France

Notes

- ^ The oldest known Neanderthal fossil in France was found in 1998 in the cave of Pradayrol, in Caniac-du-Causse, in Lot-et-Garonne. A Neanderthal incisor has been dated there to 335,000 years.[6]

- ^ Provence stelae with chevron ornamentation are relatively well dated. They have always been dated to the Middle Neolithic, and more exactly to the Late Chasséen.[26]

References

- PMID 35138885.

- ^ Price, Michael (9 February 2022). "Did Neanderthals and modern humans take turns living in a French cave?". www.science.org.

- ^ a b Jones 2009.

- ^ a b Airvaux et al. 2012.

- ^ a b c Lumley 2009.

- ^ a b Dufau, Favarel & Séronie-Vivien 2004.

- ^ Sankararaman et al. 2012.

- ^ Champagne et al. 1990.

- ^ Bourguignon et al. 2008.

- ^ Nougier 1963.

- ^ Les Sépultures néandertaliennes 1976.

- ^ Postel 2008.

- ^ Slimak, Zanolli & Higham 2022.

- ^ Dickson 1992.

- ^ a b Klein 2009.

- ^ "The Thaïs Bone, France". UNESCO Portal to the Heritage of Astronomy.

The engraving on the Thaïs bone is a non-decorative notational system of considerable complexity. The cumulative nature of the markings together with their numerical arrangement and various other characteristics strongly suggest that the notational sequence on the main face represents a non-arithmetical record of day-by-day lunar and solar observations undertaken over a time period of as much as 3½ years. The markings appear to record the changing appearance of the moon, and in particular its crescent phases and times of invisibility, and the shape of the overall pattern suggests that the sequence was kept in step with the seasons by observations of the solstices. The latter implies that people in the Azilian period were not only aware of the changing appearance of the moon but also of the changing position of the sun, and capable of synchronizing the two. The markings on the Thaïs bone represent the most complex and elaborate time-factored sequence currently known within the corpus of Palaeolithic mobile art. The artefact demonstrates the existence, within Upper Palaeolithic (Azilian) cultures c. 12,000 years ago, of a system of time reckoning based upon observations of the phase cycle of the moon, with the inclusion of a seasonal time factor provided by observations of the solar solstices.

- ^ Conneller et al. 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Rozoy 1998.

- ^ Flores-Bello et al. 2021.

- ^ National Geographic 2022.

- ^ Barras 2019.

- ^ Haak et al. 2019.

- ^ Thorpe 2015.

- ^ a b Alexander 1978.

- ^ Cassen et al 2014.

- ^ d'Anna et al. 2015.

- ^ Joussaume 1988.

- PMID 34671162.

- ^ a b Déchelette 1910.

- ^ Hatt 1958.

- ^ Gascó́ 2000.

- Unéticiantradition, but the strong technostylistic kinship between the two sword types suggests a complex interplay of influences. Their chronological position is clearly established: Middle Bronze Age 1, from about 1550 to 1450 BC according to the latest available chronological details. (Translated from French)

- ^ "Le dépôt de Blanot". archeologie.dijon.fr. Retrieved 9 April 2022.

- ^ Armbruster, Barbara (2013). "Gold and gold working of the Bronze Age". The Oxford Handbook of the European Bronze Age. pp. 454–468.

- ^ a b c d Anthony 2010.

- ^ Fischer et al. 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ebel 1976.

- ^ Bindon 1995, p. 137.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o STD 2016.

Sources

- Airvaux, Jean; Despriée, Jackie; Turq, Alain; et al. (2012). "Premières présences humaines en France entre 1,2 et 0,5 million d'années". Academia (in French). Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Thom, Alexander; Thom, Archibald Stevenson (1978). Megalithic Remains in Britain and Brittany. Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-858156-7.

- Anthony, David W. (26 July 2010). The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-3110-4. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Barras, Colin (27 March 2019). "Story of most murderous people of all time revealed in ancient DNA". New Scientist.

- Bindon, Peter (1995). "Tephrofacts and the first human occupation of the French Massif Central". Proceedings of the European Science Foundation Workshop at Tautaval (France), 1993: 129–146.

- Bourguignon, Laurence (2008). Les sociétés du Paléolithique dans un grand Sud-Ouest de la France : nouveaux gisements, nouveaux résultats, nouvelles méthodes : journées SPF, Université Bordeaux 1, Talence, 24-25 novembre 2006 (in French). Paris: Société préhistorique française. ISBN 9782913745377.

- Champagne, Fernand; Champagne, Christian; Jauzon, Pierre; et al. (1990). "Le site préhistorique des Fieux à Miers (Lot) [Etat actuel de la recherche]: Etat actuel de la recherche". Gallia préhistoire. 32 (1): 1–28. .

- Cassen, Serge; Grimaud, V; Lescop, L; et al. (2014). "The first radiocarbon dates for the construction and use of the interior of the monument at Gavrinis (Lamor-Baden, France)". Past: The Newsletter of the Prehistoric Society. 77. University College London: 1–4.

- Conneller, Chantal; Bayliss, Alex; Milner, Nicky; Taylor, Barry (2016). "The Resettlement of the British Landscape: Towards a chronology of Early Mesolithic lithic assemblage types". Internet Archaeology. 42 (42). hdl:10034/621138.

- d'Anna, André; Bosansky, Christiane; Bellot-Gurlet, Ludovic; et al. (2015). "Les stèles gravées néolithiques de Beyssan à Gargas (Vaucluse)". Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française. 112 (4): 761–768. .

- Déchelette, Joseph (1910). Manuel d'archéologie préhistorique celtique et gallo-romaine: Archéologie celtique ou protohistorique. second Âge du fer ou époque de la Tène (in French). Librairie A. Picard. ISBN 9780576199933.

- Defleur, Alban R.; Desclaux, Emmanuel (April 2019). "Impact of the last interglacial climate change on ecosystems and Neanderthals behavior at Baume Moula-Guercy, Ardèche, France". Journal of Archaeological Science. 104: 114–124. S2CID 133992282.

- Dickson, D. Bruce (July 1992). The Dawn of Belief: Religion in the Upper Paleolithic of Southwestern Europe. University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0-8165-1336-9.

- Dufau, Jean; Favarel, Jacques; Séronie-Vivien, M. (2004). "Un site pléistocène moyen à hominidé en Quercy : La grotte de Pradayrol à Caniac-du-Causse (Lot)" (in French). )

- Ebel, Charles (1976). "Chapter 2, Massilia and Rome before 390 B.C.". Transalpine Gaul: the emergence of a Roman province. Brill Archive. pp. 5–16. ISBN 90-04-04384-5.,

- Fischer, Claire-Elise; Pemonge, Marie-Hélène; Ducoussau, Isaure; et al. (April 2022). "Origin and mobility of Iron Age Gaulish groups in present-day France revealed through archaeogenomics". iScience. 25 (4): 104094. PMID 35402880.

- Flores-Bello, André; Bauduer, Frédéric; Salaberria, Jasone; et al. (May 2021). "Genetic origins, singularity, and heterogeneity of Basques". Current Biology. 31 (10): 2167–2177.e4. S2CID 232359452.

- Gascó́, Jean (1951- ) Auteur du texte (2000). "L'Âge du bronze dans la moitié sud de la France / Jean Gascó́". Histoire de la France préhistorique.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Haak, Wolfgang; Lazaridis, Iosif; Patterson, Nick; et al. (11 June 2015). "Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe". Nature. 522 (7555): 207–211. PMID 25731166.

- Hatt, Jean-Jacques (1958). "Chronique de protohistoire, IV. Nouveau projet de chronologie pour l'âge du Bronze en France". Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française. 55 (5): 304–306. .

- Jones, Tim (17 December 2009). "Lithic Assemblage Dated to 1.57 Million Years Found at Lézignan-la-Cébe, Southern France «". Anthropology.net. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- Joussaume, Roger (1988). Dolmens for the dead : megalith-building throughout the world. London: Batsford. ISBN 978-0-7134-5369-0.

- Klein, Richard G. (22 April 2009). The Human Career: Human Biological and Cultural Origins, Third Edition. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-02752-4.

- Les Sépultures néandertaliennes: colloque : Nice, vendredi 17 septembre 1976 (in French). Centre national de la recherche scientifique. 1976.

- Lumley, Henry de,. (2009). La grande histoire des premiers hommes européens. Paris: O. Jacob. ISBN 9782738123862.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link - "Doggerland - The Europe That Was | National Geographic Society". education.nationalgeographic.org. National Geographic Society. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- Nougier, Louis-René (1963). La préhistoire: essai de paléosociologie religieuse (in French). Bloud & Gay.

- Postel, B (2008). "Neandertal et la mort | Archéologia n° 458". www.archeologia-magazine.com (in French) (458): 6–11.

- Rozoy, J. (1 January 1998). "The (Re-) population of Northern France between 13,000 and 8000 BP". Quaternary International. 49–50 (1): 69–86. .

- Sankararaman, Sriram; Patterson, Nick; Li, Heng; Pääbo, Svante; Reich, David (2012). "The date of interbreeding between Neandertals and modern humans". ].

- Savatier, François (2019). "Des Néandertaliens cannibales dans la vallée du Rhône". Pourlascience.fr (in French). Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Slimak, L.; Zanolli, C.; Higham, T.; et al. (2022). "Modern human incursion into Neanderthal territories 54,000 years ago at Mandrin, France". Science Advances. 8 (6): eabj9496. PMID 35138885.

- "Stratigraphische Tabelle von Deutschland 2016" (PDF). www.stratigraphie.de. Deutsche Stratigraphische Kommission. Retrieved 7 September 2022.

- Thorpe, Nick (2015). "The Atlantic Mesolithic-Neolithic Transition". In Fowler, Chris (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Neolithic Europe. Oxford University Press. p. 221. ISBN 978-0191666889.

Further reading

- Brunel, Samantha; Bennett, E. Andrew; Cardin, Laurent; et al. (9 June 2020). "Ancient genomes from present-day France unveil 7,000 years of its demographic history". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117 (23): 12791–12798. PMID 32457149.

- Forbes, Peter (29 March 2018). "Who We Are and How We Got Here by David Reich review – new findings from ancient DNA". the Guardian.

- Gaucher, Gilles (1 January 1993). L'Âge du bronze en France (in French). Presses universitaires de France (réédition numérique FeniXX). ISBN 978-2-13-066958-6.

- Giacobini, Giacomo (January 2006). "Les sépultures du Paléolithique supérieur : la documentation italienne". Comptes Rendus Palevol (in French). 5 (1–2): 169–176. . Retrieved 3 September 2022.

- Gibbons, Ann (24 July 2015). "Revolution in human evolution". Science. 349 (6246): 362–366. PMID 26206910.

- Haak, Wolfgang; Lazaridis, Iosif; Patterson, Nick; et al. (11 June 2015). "Massive migration from the steppe was a source for Indo-European languages in Europe". Nature. 522 (7555): 207–211. PMID 25731166.

- Hallegouët, Bernard; Hinguant, Stéphan; Gebhardt, Anne; et al. (1992). "Le gisement Paléolithique inférieur de Ménez-Drégan 1 (Plouhinec, Finistère)". Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française (in French). 89 (3): 77–81. .

- Hatt, Jean-Jacques (1954). "Pour une nouvelle chronologie de la Protohistoire française". Bulletin de la Société préhistorique de France. 51 (7): 379–384. .

- Olalde, Iñigo; Brace, Selina; Allentoft, Morten E.; et al. (March 2018). "The Beaker phenomenon and the genomic transformation of northwest Europe". Nature. 555 (7695): 190–196. PMID 29466337.

- Rivollat, Maïté; Jeong, Choongwon; Schiffels, Stephan; et al. (29 May 2020). "Ancient genome-wide DNA from France highlights the complexity of interactions between Mesolithic hunter-gatherers and Neolithic farmers". Science Advances. 6 (22): eaaz5344. PMID 32523989.

External links

- French National Museum of Antiquities in the Château of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (in French)

- Lascaux Cave at the Library of Congress Web Archives (archived 2002-11-13) – official Lascaux Web site, from the French Ministry of Culture

- The Dawn of Rock Art – an article summarizing the earliest known rock art, with a focus on recently discovered painted caves in Europe, Grotto Chauvet

- La Tène site at the Wayback Machine (archived 2009-02-07) – brief text, illustrations (in French)

![Gavrinis passage grave, Brittany, c. 4200 BC.[25]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a2/Gavrinis_2.jpg/120px-Gavrinis_2.jpg)

![Stele, Chasséen culture, 4th millennium BC.[b]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fc/Lauris_1.jpg/70px-Lauris_1.jpg)

![The Bell Beaker culture had domesticated horses.[28]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/3f/Horses1.png/117px-Horses1.png)

![Middle Bronze Age sword, c. 1550 BC.[32]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/62/Bronze_swords-MGR_Lyon-IMG_9733.jpg/100px-Bronze_swords-MGR_Lyon-IMG_9733.jpg)

![Bronze jewelry, Urnfield culture, c. 1000 BC.[33]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/13/Dijon_-_Mus%C3%A9e_arch%C3%A9ologique_de_Dijon_-_04.jpg/81px-Dijon_-_Mus%C3%A9e_arch%C3%A9ologique_de_Dijon_-_04.jpg)

![Gold torc, Atlantic Bronze Age, c. 1200-1000 BC.[34]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8b/Guines_gold_torc_1.jpg/120px-Guines_gold_torc_1.jpg)