Prehistory of the Netherlands

| History of the Netherlands |

|---|

|

|

|

The

A succession of cultural groups, such as the

Historical changes to the landscape

The prehistory of the area that is now the Netherlands was largely shaped by its constantly shifting, low-lying geography.

-

The Netherlands in 5500 BC

-

The Netherlands in 3850 BC

-

The Netherlands in 2750 BC

-

The Netherlands in 500 BC

-

The Netherlands in AD 50

(including old river courses and riverbank breaches which have filled up with silt or peat)

Earliest groups of hunter-gatherers (before 5000 BC)

The oldest human (Neanderthal) traces, believed to be about 70,000 years old, were found in higher soils near Maastricht.

The area that is now the Netherlands was inhabited by early humans at least 37,000 years ago, as attested by flint tools discovered in Woerden in 2010.[1] In 2009 a fragment of a 40,000-year-old Neanderthal skull was found in sand dredged from the North Sea floor off the coast of Zeeland.[2]

During the last ice age, the Netherlands had a

At the end of the

The arrival of farming (around 5000–4000 BC)

There are a number of theories about the arrival of agriculture in the Netherlands. The first is that between 4800 and 4500 BC, the Swifterbant people started to adopt from the neighbouring

The second is that agriculture arrived in the Netherlands somewhere around 5000 BC with the Linear Pottery culture, who were probably central European farmers. Agriculture was practiced only on the loess plateau in the very south (southern Limburg), but even there it was not established permanently. Farms did not develop in the rest of the Netherlands.

There is also a third theory that there is some evidence of small settlements in the rest of the country. These people made the switch to animal husbandry sometime between 4800 BC and 4500 BC. Dutch archaeologist Leendert Louwe Kooijmans wrote, "It is becoming increasingly clear that the agricultural transformation of prehistoric communities was a purely indigenous process that took place very gradually."[6] This transformation took place as early as 4300 BC–4000 BC[8] and featured the introduction of grains in small quantities into a traditional broad-spectrum economy.[9]

Funnelbeaker and other cultures (around 4000–3000 BC)

The

To the west, the Vlaardingen culture (around 2600 BC), an apparently more primitive culture of hunter-gatherers survived well into the Neolithic period.

-

Reconstruction of a Funnelbeaker culture house

-

Funnelbeaker pottery

Corded Ware and Bell Beaker cultures (around 3000–2000 BC)

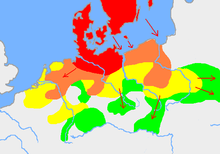

Around 2950 BCE there was a transition from the

The

The Corded Ware and Bell Beaker cultures were not indigenous to the Netherlands but were pan-European in nature, extending across much of northern and central Europe.

The first evidence of the use of the wheel dates from this period, about 2400 BC.[citation needed] This culture also experimented with working with copper. Evidence of this, including stone anvils, copper knives, and a copper spearhead, was found on the Veluwe.[citation needed] Copper finds show that there was trade with other areas in Europe, as natural copper is not found in Dutch soil.

-

Bell Beaker ceramic vessel

-

Beaker, copper dagger and metalworking tools

-

Copper axe, Bell Beaker culture

-

Beaker, dagger, stone wristguard and arrowheads

Bronze Age (around 2000–800 BC)

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2022) |

The

Most of the Bronze Age objects found in the Netherlands have been found in Drenthe.[citation needed] One item shows that trading networks during this period extended a far distance. Large bronze situlae (buckets) found in Drenthe were manufactured somewhere in eastern France or in Switzerland. They were used for mixing wine with water (a Roman/Greek custom). The many finds in Drenthe of rare and valuable objects, such as tin-bead necklaces, suggest that Drenthe was a trading centre in the Netherlands in the Bronze Age.[citation needed]

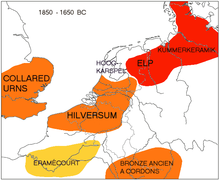

The

In the north, the

-

Bronze Age house reconstruction

-

Ceremonial Sword of Jutphaas, c. 1800 - 1500 BC

-

Echten sword, Elp culture, c. 1600 BC

The pre-Roman period (800 BC – 58 BC)

Iron Age

The

Iron ore brought a measure of prosperity and was available throughout the country, including bog iron. Smiths travelled from settlement to settlement with bronze and iron, fabricating tools on demand. The King's grave of Oss (700 BC) was found in a burial mound, the largest of its kind in Western Europe and containing an iron sword with an inlay of gold and coral.

In Oss, a grave dating from around 500 BC was found in a burial mound 52 metres wide (and thus the largest of its kind in western Europe). Dubbed the "king's grave" (Vorstengraf (Oss)), it contained extraordinary objects, including an iron sword with an inlay of gold and coral.

In the centuries just before the arrival of the Romans, northern areas formerly occupied by the Elp culture emerged as the probably Germanic Harpstedt culture[17] while the southern parts were influenced by the Hallstatt culture and assimilated into the Celtic La Tène culture. The contemporary southern and western migration of Germanic groups and the northern expansion of the Hallstatt culture drew these peoples into each other's sphere of influence.[18] This is consistent with Caesar's account of the Rhine forming the boundary between Celtic and Germanic tribes.

-

The King's grave of Oss seen from the air

Arrival of Germanic groups

The Germanic tribes originally inhabited southern Scandinavia, Jutland peninsula and northern Germany,[19] but subsequent Iron Age cultures of the same region, like Wessenstedt (800–600 BC) and Jastorf, also belonged to this grouping.[20] The climate deteriorating in Scandinavia around 850 BC to 760 BC and later and faster around 650 BC might have triggered migrations. Archaeological evidence suggests around 750 BC a relatively uniform Germanic people came to the Netherlands from the Vistula and southern Scandinavia.[19] In the west, the newcomers settled the coastal floodplains for the first time, since in adjacent higher grounds the population had increased and the soil had become exhausted.[21]

By the time this migration was complete, around 250 BC, a few general cultural and linguistic groupings had emerged.[22][23]

One grouping – labelled the "

A second grouping, which scholars subsequently dubbed the "Weser–Rhine Germanic" (or "Rhine–Weser Germanic"), extended along the middle Rhine and Weser and inhabited the southern part of the Netherlands (south of the great rivers). This group, also sometimes referred to as the "Istvaeones", consisted of tribes that would eventually develop into the Salian Franks.[23]

Celts in the south

The

In March 2005 17 Celtic coins were found in

Although it is rare for hoards to be found, in past decades loose Celtic coins and other objects have been found throughout the central, eastern and southern part of the Netherlands. According to archaeologists these finds confirmed that at least the Meuse (Dutch: Maas) river valley in the Netherlands was within the influence of the La Tène culture. Dutch archaeologists even speculate that Zutphen (which lies in the centre of the country) was a Celtic area before the Romans arrived, not a Germanic one at all.[27]

Scholars debate the actual extent of the Celtic influence.

The Nordwestblock theory

Some scholars (De Laet, Gysseling, Hachmann, Kossack & Kuhn) have speculated that a separate ethnic identity, neither Germanic nor Celtic, survived in the Netherlands until the Roman period. They see the Netherlands as having been part of an Iron Age "Nordwestblock" stretching from the Somme to the Weser.[30][31] Their view is that this culture, which had its own language, was being absorbed by the Celts to the south and the Germanic peoples from the east as late as the immediate pre-Roman period.

The first author to describe the coast of Holland and Flanders was the Greek geographer Pytheas, who noted in c. 325 BC that in these regions, "more people died in the struggle against water than in the struggle against men."[32]

See also

External links

References

- ^ "Neanderthal may not be the oldest Dutchman | Radio Netherlands Worldwide". Rnw.nl. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ "Neanderthal fossil discovered in Zeeland province | Radio Netherlands Worldwide". Rnw.nl. 16 June 2009. Archived from the original on 19 May 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ Van Zeist, W. (1957), "De steentijd van Nederland", Nieuwe Drentse Volksalmanak, vol. 75, pp. 4–11

- ^ a b "The Mysterious Bog People – Background to the exhibition". Canadian Museum of Civilization Corporation. 5 July 2001. Archived from the original on 9 March 2007. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

- ^ Van Zeist, W. (1957), "De steentijd van Nederland", Nieuwe Drentse Volksalmanak, 75: 4–11

- ^ a b Louwe Kooijmans, L.P., "Trijntje van de Betuweroute, Jachtkampen uit de Steentijd te Hardinxveld-Giessendam", 1998, Spiegel Historiael 33, pp. 423–428

- ^ Volkskrant 24 August 2007 "Prehistoric agricultural field found in Swifterbant, 4300–4000 BC Archived 19 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine"

- ^ Volkskrant 24 August 2007 "Prehistoric agricultural field found in Swifterbant, 4300–4000 BC"

- ^ Raemakers, Daan. "De spiegel van Swifterbant Archived 10 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine", University of Groningen, 2006.

- ISBN 90-269-4448-9, NUGI 644

- ^ Lanting, J.N. & J.D. van der Waals, (1976), "Beaker culture relations in the Lower Rhine Basin", [page needed], in Lanting et al. (Eds) Glockenbechersimposion Oberried 1974. Bussum-Haarlem: Uniehoek N.V.

- ^ [full citation needed], p. 93, in J. P. Mallory and John Q. Adams (Eds), The Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture, Fitzroy Dearborn, 1997.

- ISBN 978-90-8890-084-6.

- ^ Fokkens, Harry. "The Periodisation of the Dutch Bronze Age: a Critical Review" (PDF). Open Access Leiden University. Faculty of Archaeology, Leiden. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ^ https://www.researchgate.net/figure/The-Wageningen-hoard-comprising-amongst-others-a-stone-axe-flat-axe-halberd-with_fig4_365043233

- ^ According to "Het Archeologisch Basisregister" (ABR), version 1.0 November 1992, [1], Elp Kümmerkeramik is dated BRONSMA (early MBA) to BRONSL (LBA) and this has been standardized by "De Rijksdienst voor Archeologie, Cultuurlandschap en Monumenten" (RACM) as being at the period starting at 1800 BC and ending at 800 BC.[failed verification] [dead link]

- ^ Mallory, J.P., In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language, Archaeology and Myth, London: Thames & Hudson, 1989, p. 87.

- ^ Butler, J.J., Nederland in de bronstijd, Bussum: Fibula-Van Dishoeck, 1969, p. [page needed].

- ^ ISBN 0-14-051054-0Volume 1. p. 109.

- ^ The New Encyclopaedia Britannica, 15th edition, 20:67

- ^ ISBN 90-5345-303-2, 2006, pp. 67, 81–82

- ^ The New Encyclopædia Britannica, 15th edition, 22:641–642

- ^ a b c de Vries, Jan W., Roland Willemyns and Peter Burger, Het verhaal van een taal, Amsterdam: Prometheus, 2003, pp. 12, 21–27

- ^ Cunliffe, Barry. The Ancient Celts. Penguin Books, 1997, pp. 39–67.

- ^ Achtergrondinformatie bij de muntschat van Maastricht-Amby, Municipality of Maastricht, 2008.

- ^ Unieke Keltische muntschat ontdekt in Maastricht Archived 2 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Archeonet.be, 15 November 2008. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- ^ a b Het urnenveld van het Meijerink, Municipality of Zutphen, Retrieved 0 October 20116.

- ^ Delrue, Joke, University of Ghent[citation needed]

- ^ van Durme, Luc, "Oude taaltoestanden in en om de Nederlanden. Een reconstructie met de inzichten van M. Gysseling als leidraad" in Handelingen van de Koninklijke commissie voor Toponymie en Dialectologie, LXXV/2003.

- ^ Hachmann, Rolf, Georg Kossack and Hans Kuhn, Völker zwischen Germanen und Kelten, 1986, pp. 183–212

- ^ Lendering, Jona, "Germania Inferior" Archived 7 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Livius.org. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- ^ Lendering, Jona. "The Edges of the Earth (3) – Livius". www.livius.org. Retrieved 28 February 2019.