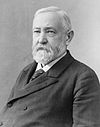

Presidency of Benjamin Harrison

| |

| Presidency of Benjamin Harrison March 4, 1889 – March 4, 1893 | |

| Cabinet | See list |

|---|---|

| Party | Republican |

| Election | 1888 |

| Seat | White House |

|

| |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Senator from Indiana

23rd President of the United States

Presidential campaigns

Post-presidency

|

||

Harrison and the Republican-controlled

Election of 1888

The initial favorite for the

Harrison represented Indiana in the United States Senate from 1881 to 1887, but lost his 1886 bid for re-election.[3] In February 1888, Harrison announced his candidacy for the Republican presidential nomination, declaring himself a "living and rejuvenated Republican."[4] He placed fifth on the first ballot at the 1888 Republican convention, with Sherman in the lead; the next few ballots showed little change.[5] The Blaine supporters shifted their support among different candidates, and when they shifted to Harrison, they found a candidate who could attract the votes of many other delegations.[6] Harrison was nominated as the party's presidential candidate on the eighth ballot, by a count of 544 to 108 votes.[7] Levi P. Morton of New York was chosen as his running mate.[8]

Harrison's opponent in the general election was incumbent President

Although Harrison had made no political bargains, his supporters had given many pledges upon his behalf. When Boss

Inauguration

Harrison was sworn into office on March 4, 1889, by

In his speech, Benjamin Harrison credited the nation's growth to the influences of education and religion, urged the cotton states and mining territories to attain the industrial proportions of the eastern states, and promised a protective tariff. Concerning commerce, he said, "If our great corporations would more scrupulously observe their legal obligations and duties, they would have less call to complain of the limitations of their rights or of interference with their operations."

Administration

| The Harrison cabinet | ||

|---|---|---|

| Office | Name | Term |

Jeremiah McLain Rusk | 1889–1893 | |

Harrison's cabinet choices alienated pivotal Republican operatives from New York to Pennsylvania to Iowa and prematurely compromised his political power and future.

For the important position of Secretary of the Treasury, Harrison rejected Thomas C. Platt and Warner Miller, two powerful New York Republicans who fought for control of their state party. He instead selected William Windom, a native Midwesterner who lived in New York and who had served in the same position under Garfield.[28] New York Republicans were also represented in the cabinet by Benjamin F. Tracy, who was appointed Secretary of the Navy.[29] Former Governor Charles Foster of Ohio succeeded Windom upon the latter's death in 1891.[24] Postmaster General John Wanamaker represented Pennsylvania Republicans, many of whom were disappointed that their state party did not receive a more prominent cabinet seat.[30] For the position of Secretary of the Agriculture, which had been established in the waning days of Cleveland's term, Harrison appointed Wisconsin Governor Jeremiah M. Rusk.[31] John Noble, a railroad attorney with a reputation for incorruptibility, became the head of the scandal-plagued Department of the Interior.[32] Redfield Proctor, a native of Vermont who had played a key role in Harrison's nomination, was rewarded with the position of Secretary of War. Proctor resigned in 1891 to take a Senate seat, at which point he was replaced by Stephen B. Elkins.[32] Harrison's close friend and former law partner, William H. H. Miller, became Attorney General.[29] Harrison's normal schedule provided for two full cabinet meetings per week, as well as separate weekly one-on-one meetings with each cabinet member.[33]

Judicial appointments

Harrison appointed four justices to the

Harrison signed the

States admitted to the Union

More states were admitted during Harrison's presidency than any other. When Harrison took office, no new states had been admitted to the Union in more than a decade, owing to Congressional Democrats' reluctance to admit states that they believed would send Republican members. Seeking to bolster the party's majorities in the Senate, Republicans pushed bills admitting new states through the lame duck session of the 50th Congress.[36] North Dakota, South Dakota, Montana, and Washington all became states in November 1889.[37] The following July, Idaho and Wyoming were also admitted.[37] These states collectively sent twelve Republican senators to the 51st Congress.[38]

Antitrust law

Members of both parties were concerned with the growth and power of

Along with the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887, the Sherman Act represented one of the first major federal steps taken by the federal government to regulate the economy.[39] Harrison approved of the law and its intent, but his administration was not particularly vigorous in enforcing it.[40] The Department of Justice was generally too understaffed to pursue complex antitrust cases, and enforcement was further hampered by the vague language of the act and narrow interpretation of judges.[41] Despite these hindrances, the government successfully concluded one case during Harrison's time in office (against a Tennessee coal company), and initiated several other cases against trusts.[40] The relatively limited enforcement powers and the Supreme Court's narrow interpretation of the law would eventually inspire passage of the Clayton Antitrust Act of 1914.[42]

Tariff

Harrison took an active role in the tariff debate, hosting dinner parties in which he would cajole members of Congress for their support of a new tariff bill.[16] Representative William McKinley and Senator Nelson W. Aldrich introduced the McKinley Tariff, which would raise the tariff and make some rates intentionally prohibitive so as to discourage imports.[47] At Secretary of State James Blaine's urging, Harrison attempted to make the tariff by adding reciprocity provisions, which would allow the president to reduce rates when other countries reduced their own tariffs on American exports.[48] The reciprocity features of the bill delegated an unusually high amount of power to the president for the time, as the president was granted the power to unilaterally modify tariff rates.[48] The tariff was removed from imported raw sugar, and sugar growers in the United States were given a two cent per pound subsidy on their production.[47] Congress passed the bill after Republican leaders won the votes of Western senators through passage of the Sherman Antitrust Act and other concessions, and Harrison signed the McKinley Tariff into law in October 1890.[49]

The Harrison administration negotiated more than a dozen reciprocity agreements with European and Latin American nations in an attempt to expand U.S. trade.[50] Even with the reductions and reciprocity, the McKinley Tariff enacted the highest average rate in American history, and the spending associated with it contributed to the reputation of the "Billion-Dollar Congress".[48]

Currency

One of the most volatile questions of the 1880s was whether the currency should be backed by gold and silver, or by gold alone.[51] Owing to worldwide deflation in the late 19th century, a strict gold standard had resulted in reduction of incomes without the equivalent reduction in debts, pushing debtors and the poor to call for silver coinage as an inflationary measure.[52] Because silver was worth less than its legal equivalent in gold, taxpayers paid their government bills in silver, while international creditors demanded payment in gold, resulting in a depletion of the nation's gold supply.[52] The issue cut across party lines, with western Republicans and southern Democrats joining in the call for the free coinage of silver, and both parties' representatives in the northeast holding firm for the gold standard.[52]

The silver coinage issue had not been much discussed in the 1888 campaign.[53] Harrison attempted to steer a middle course between the two positions, advocating a free coinage of silver, but at its own value, not at a fixed ratio to gold.[54] Congress did not adopt Harrison's proposal, but in July 1890, Senator Sherman won passage of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act. The Sherman Silver Purchase Act increased the amount of silver the government was required to purchase on a recurrent monthly basis to 4.5 million ounces.[55] Believing that the bill would end the controversy over silver, Harrison signed the bill into law.[56] The effect of the bill, however, was the increased depletion of the nation's gold supply, a problem that would persist until after Harrison left office.[57] The bill and the silver debate also split the Republican Party, leading to the rise of the Silver Republicans, an influential bloc of Western Congressmen who backed the free coinage of silver.[58] Many of these Silver Republicans would later join the Democratic Party.[58]

Civil service reform and pensions

Civil service reform was a prominent issue following Harrison's election. Harrison had campaigned as a supporter of the merit system, as opposed to the spoils system.[59] Although the passage of the 1883 Pendleton Act had decreased the role of patronage in assigning government positions, Harrison spent much of his first months in office deciding on political appointments.[60] Congress was severely divided on civil service reform and Harrison was reluctant to address the issue for fear of alienating either side. The issue became a political football of the time and was immortalized in a cartoon captioned "What can I do when both parties insist on kicking?"[61] Harrison appointed Theodore Roosevelt and Hugh Smith Thompson, both reformers, to the Civil Service Commission, but otherwise did little to further the reform cause.[62] Harrison largely ignored Roosevelt, who frequently called for an expansion of the merit system and complained about the administration of Postmaster General Wanamaker.[62]

Harrison's solution to the growing surplus in the federal treasury was to increase pensions for Civil War veterans, the great majority of whom were Republicans. He presided over the enactment of the

Civil rights

In violation of the

Following the failure to pass the bill, Harrison continued to speak in favor of African American civil rights in addresses to Congress.[69] Attorney General Miller conducted prosecutions for violation of voting rights in the South, but white juries often refused to convict or indict violators.[70] He argued that if the states have authority over civil rights, then "we have a right to ask whether they are at work upon it."[71] Harrison also supported a bill proposed by Senator Henry W. Blair, which would have granted federal funding to schools regardless of the students' races.[72] Though similar bills had garnered strong Republican support during the 1880s, Blair's bill was defeated in the Senate in 1890 after several Republicans voted against it.[73] Harrison also endorsed an unsuccessful constitutional amendment to overturn the Supreme Court's holding in the Civil Rights Cases, which had declared much of the Civil Rights Act of 1875 unconstitutional, but no action was taken on such an amendment.[74]

1890 midterm elections

By the end of the 51st Congress, Harrison and the Republican-controlled allies had passed one of the most ambitious peacetime domestic legislative programs in U.S. history,

National forests

In March 1891 Congress enacted and Harrison signed the

That the President of the United States may, from time to time, set apart and reserve, in any State or Territory having public land bearing forests, in any part of the public lands wholly or in part covered with timber or undergrowth, whether of commercial value or not, as public reservations, and the President shall, by public proclamation, declare the establishment of such reservations and the limits thereof.[79]

Within a month of the enactment of this law Harrison authorized the first forest reserve, to be located on public domain adjacent to Yellowstone Park, in Wyoming. Other areas were so designated by Harrison, bringing the first forest reservations total to 22 million acres in his term.[80] Harrison was also the first to give a prehistoric Indian Ruin, Casa Grande in Arizona, federal protection.[81]

Native American policy

During Harrison's administration, the

Soon after taking office, Harrison signed an appropriations bill that opened parts of Indian Territory to white settlement. The territory had been established earlier in the 19th century for the resettlement of the "Five Civilized Tribes," and portions of the territory known as the Unassigned Lands had not yet been granted to any tribe. In the Land Rush of 1889, 50,000 settlers moved into the Unassigned Lands to establish land claims.[91] In the 1890 Oklahoma Organic Act, Oklahoma Territory was created out of the western half of Indian Territory.

Federal immigration control and Ellis Island

In 1890, President Harrison approved the assumption of federal control over immigration, ending the previous policy of leaving it to the states to regulate. Further, in 1891, he signed into law the Immigration Act of March 3, creating a federal immigration agency in the Treasury Department, establishing regulations on the type of aliens to be admitted and those for whom admission was to be barred, and funding the construction of the first federal immigration station on Ellis Island, in New York harbor, the nation's busiest port for arriving immigrants. Funding also provided for smaller immigration facilities at other port cities, including Boston, Philadelphia and Baltimore.

Technology and military modernization

During Harrison's time in office, the United States was continuing to experience advances in science and technology, and Harrison was the earliest president whose voice is known to be preserved. That ⓘ was originally made on a wax phonograph cylinder in 1889 by Gianni Bettini.[92] Harrison also had electricity installed in the White House for the first time by Edison General Electric Company, but he and his wife would not touch the light switches for fear of electrocution and would often go to sleep with the lights on.[93]

The United States Navy fell into obsolescence following the Civil War, though reform and expansion had begun under President Chester A. Arthur.[94] When Harrison took office there were only two commissioned warships in the Navy. In his inaugural address he said, "construction of a sufficient number of warships and their necessary armaments should progress as rapidly as is consistent with care and perfection."[95] Harrison's support for naval expansion was aided and encouraged by several naval officers, who argued that the navy would be useful for protecting American trade projecting American power.[96] In 1890, Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan published The Influence of Sea Power upon History, an influential work of naval strategy that called for naval expansion; Harrison strongly endorsed it, and Mahan was restored to his position of President of the Naval War College.[97] Secretary of the Navy Tracy spearheaded the rapid construction of vessels, and within a year congressional approval was obtained for building of the warships Indiana, Texas, Oregon and Columbia. By 1898, with the help of the Carnegie Corporation, no less than ten modern warships, including steel hulls and greater displacements and armaments, had transformed the United States into a legitimate naval power. Seven of these had begun during the Harrison term.[98]

The United States Army had also been largely neglected since the Civil War, despite the continuing American Indian Wars. When Harrison took office, there were roughly 28,000 officers and enlisted men, and much of the equipment was inferior to that of European armies. Secretary of War Proctor sought to institute several reforms, including an improved diet and the granting of furloughs, resulting in a decline of the desertion rate. Promotions for officers began to be granted based on the branch of service rather than on a regimental basis, and those subject to promotion were required to pass examinations. The Harrison administration also re-established the position of United States Assistant Secretary of War to serve as the second-ranking member of the War Department. Harrison's reform efforts halved the desertion rate, but otherwise the army remained in largely the same state at the end of his tenure.[99]

Standardization of place names

By executive order, Harrison established the Board on Geographical Names in 1890.[100] The board was tasked with standardizing the spelling of the names of communities and municipalities within the United States; most towns with apostrophes or plurals as part of their names were rewritten as singular (e.g. Weston's Mills became Weston Mills)[101] and places that ended in "burgh" were truncated to end in "burg." In one particularly controversial case, a city in Pennsylvania was shortened from Pittsburgh to Pittsburg, only to reverse the decision 20 years later after local residents continued to use the "Pittsburgh" spelling.[102]

Foreign policy

Harrison appreciated the forces of nationalism and imperialism which were inevitably pulling the United States onward into playing a more important part in world affairs as it grew rapidly in financial and economic prowess. While the ineffective diplomatic corps was still mired in patronage, the rapidly growing consular service vigorously promoted commerce abroad.[103] In a speech in 1891, Harrison proclaimed that the United States was in a "new epoch" of trade and that the expanding navy would protect oceanic shipping and increase American influence and prestige abroad.[104] The increasing importance of the United States in world affairs was reflected in the act of Congress in 1893 which raised the rank of the most important diplomatic representatives abroad from minister plenipotentiary to ambassador.[25][26][27]

Latin America

Harrison and Blaine agreed on an ambitious foreign policy that emphasized commercial reciprocity with other nations.[105] Their goal was to replace Britain as the dominant commercial power in Latin America.[106] The First International Conference of American States met in Washington in 1889; Harrison set an aggressive agenda including customs and currency integration and named a bipartisan conference delegation led by John B. Henderson and Andrew Carnegie. Though the conference failed to achieve any diplomatic breakthrough, it did succeed in establishing an information center that became the Pan American Union.[107] In response to the diplomatic bust, Harrison and Blaine pivoted diplomatically and initiated a crusade for tariff reciprocity with Latin American nations; the Harrison administration concluded eight reciprocity treaties among these countries.[108] The Harrison administration did not pursue reciprocity with Canada, as Harrison and Blaine believed that Canada was an integral part of the British economic bloc and could never be integrated into a trade system dominated by the U.S.[109] On another front, Harrison sent Frederick Douglass as ambassador to Haiti, but failed in his attempts to establish a naval base there.[110]

Samoa

By 1889, the United States, Great Britain and Germany were locked in an escalating

European embargo of U.S. pork

In response to vague reports of

Crises in Aleutian Islands and Chile

The first international crisis Harrison faced arose from disputed fishing rights on the Alaskan coast. After Canada claimed fishing and sealing rights around many of the Aleutian Islands, the U.S. Navy seized several Canadian ships.[122] In 1891, the administration began negotiations with the British that would eventually lead to a compromise over fishing rights after international arbitration, with the British government paying compensation in 1898.[123]

In 1891, a new diplomatic crisis, known as the

Tensions increased to the brink of war – Harrison threatened to break off diplomatic relations unless the United States received a suitable apology, and said the situation required "grave and patriotic consideration". The president also remarked, "If the dignity as well as the prestige and influence of the United States are not to be wholly sacrificed, we must protect those who in foreign ports display the flag or wear the colors."[127] A recuperated Blaine made brief conciliatory overtures to the Chilean government which had no support in the administration; he then reversed course and joined the chorus for unconditional concessions and apology by the Chileans. The Chileans ultimately obliged, and war was averted. Theodore Roosevelt later applauded Harrison for his use of the "big stick" in the matter.[128][129]

Annexation of Hawaii

The United States had reached a reciprocity treaty with Hawaii in 1875, and since had then had blocked Japanese and British efforts to take control of the Hawaii. Harrison sought to annex the country, which held a strategic position in the Pacific Ocean,[130] and hosted

a growing sugar business controlled by American settlers.

Vacations and travel

The Harrisons made many trips out of the capital, which included speeches at most stops – including Philadelphia, New England, Indianapolis and Chicago. The president typically made his best impression speaking before large audiences, as opposed to more intimate settings.[137] The most notable of his presidential trips was a five-week tour of the west in the spring of 1891, aboard a lavishly outfitted train.[138] Harrison enjoyed a number of short trips out of the capital—usually for hunting—to nearby Virginia or Maryland.[139]

During the hot Washington summers, the Harrisons took refuge in

Election of 1892

By 1892, the treasury surplus had evaporated and the nation's economic health was worsening – precursors to the eventual Panic of 1893.[141] Although Harrison had cooperated with Congressional Republicans on legislation, several party leaders withdrew their support due to discontent over Harrison's appointments. Matthew Quay, Thomas Platt, and Thomas Reed quietly organized the Grievance Committee, the ambition of which was to initiate a dump-Harrison offensive.[142] Many of Harrison's detractors persisted in pushing for an incapacitated Blaine, though he announced that he was not a candidate in February 1892.[143] Some party leaders still hoped to draft Blaine into running, and speculation increased when he resigned at the 11th hour as Secretary of State in June.[144] At the convention in Minneapolis, Harrison prevailed on the first ballot, but encountered significant opposition, with Blaine and William McKinley both receiving votes on the lone ballot.[145] At the convention, Vice President Morton was dropped from the ticket, and was replaced by Ambassador Whitelaw Reid.

The Democrats renominated former President Cleveland, making the 1892 election a rematch of the one four years earlier. The tariff revisions of the past four years had made imported goods so expensive that many voters had begun to favor lowering the tariff.

Harrison's wife Caroline began a critical struggle with tuberculosis earlier in 1892 and two weeks before the election, on October 25, she died.[149] Her role as First Lady was filled by their daughter, Mary Harrison McKee for the balance of Harrison's presidency.[150] Mrs. Harrison's terminal illness and the fact that both major candidates had served in the White House called for a low key campaign, and resulted in neither of them actively campaigning personally.[151]

Cleveland ultimately won the election by 277 electoral votes to Harrison's 145, the most decisive margin in 20 years.

Historical reputation

As a one-term president, and one of several Republicans to serve during a short span in the late 19th century, Harrison is one of the least well-known presidents, and is perhaps best known as the only president to be the grandson of another president.[157] A 2012 article in New York selected Harrison as the "most forgotten president."[158] Closely scrutinized by Democrats, Harrison's reputation was largely intact when he left the White House.[159] Following the Panic of 1893, Harrison became more popular in retirement.[160] Historian Heather Cox Richardson writes that Harrison has largely escaped blame for the Panic of 1893, with both the contemporary general public and many later historians primarily faulting Grover Cleveland for the economic crisis, which was one of the worst recessions in U.S. history.[161] Biographer Ray E. Boomhower writes that, in the decades after Harrison left office, historians generally ranked Harrison "in the middle of the pack and even lower" among all U.S. presidents; Boomhower argues that a contributing factor to this low standing was the fact that no biography on Harrison was published until the release of a three-volume biography by Harry J. Sievers in the 1950s and 1960s.[162]

Harrison's legacy among historians is scant, and "general accounts of his period inaccurately treat Harrison as a cipher".

Because of his lack of personal passion and the failure of anything truly eventful, such as a major war, during his administration, Harrison, along with every other President from the post-Reconstruction era to 1900, has been assigned to the rankings of mediocrity. He has been remembered as an average President, not among the best but certainly not among the worst.[170]

Many recent historians have recognized the importance of the Harrison administration in influencing the foreign policy of the late nineteenth century.[163] Historians have often given Secretary of State Blaine credit for foreign-policy initiatives but historian Charles Calhoun argues that Harrison was more responsible for the success of trade negotiations, the buildup of the steel Navy, overseas expansion, and emphasis on the American role in dominating the hemisphere through the Monroe Doctrine. The major weakness which Calhoun sees was that the public and indeed the grassroots Republican Party was not fully prepared for this onslaught of major activity.[171][172] Nonetheless, the Sherman Anti-Trust Act, signed into law by Harrison, remains in effect over 120 years later,[173] and Harrison's conservationist efforts would be continued under presidents such as Theodore Roosevelt.[165]

Harrison's support for African American voting rights and education would be the last significant attempts to protect civil rights until the 1930s.[173] Though he writes that Harrison had a "far better than average civil rights record," Clay S. Jenkinson of Governing criticizes Harrison's policies towards Native Americans, in particular his role in the Wounded Knee Massacre.[174] Richardson similarly argues that the root cause of the Wounded Knee Massacre was the Harrison administration's efforts to curry favor in South Dakota through the opening of Native American lands to settlers, thereby gaining support for Republicans ahead of the 1890 Senate elections.[175] Richardson also argues that the Harrison administration and their allies in the Republican Party deserve much of the blame for the Panic of 1893, as their demonization of Democratic policies during the 1892 election and the presidential transition period led to panic among investors, and Harrison's subsequent inaction during the early days of the economic crisis allowed it to spiral into one of the worst recessions in U.S. history.[161]

References

- ^ a b Calhoun 2005, p. 47.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 8.

- ^ Calhoun 2005, pp. 45–46.

- ^ a b c "Benjamin Harrison: Campaigns and Elections". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. 4 October 2016. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ Calhoun 2005, p. 50.

- ^ Calhoun 2005, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Wallace, p. 271.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 9.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 11.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 10.

- ^ Calhoun 2005, p. 43; Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 13.

- ^ Calhoun 2005, p. 57.

- ^ "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved November 5, 2008.

- ^ Calhoun 2005, pp. 55, 60.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 14.

- ^ a b c Calhoun 2002, p. 252.

- ^ a b Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 1.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 3.

- ^ "Benjamin Harrison – Inauguration". Advameg, Inc., Profiles of U.S. Presidents. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 22–30.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 33.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 20–22.

- ^ a b c Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 88.

- ^ a b Allan Spetter, "Harrison and Blaine: Foreign Policy, 1889 1893." Indiana Magazine of History (1969) 65#3:214-27. online

- ^ a b A.T. Volwiler, "Harrison, Blaine, and American Foreign Policy, 1889–1893" Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 79#4 1938) pp. 637–648 online

- ^ a b Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 111.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 23–24.

- ^ a b Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 26–27.

- ^ a b Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 27.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 85.

- ^ a b c d e Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 188–190.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 189–190.

- ^ White, pp. 626–627.

- ^ a b Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 44–45.

- ^ White, p. 627.

- ^ a b Spetter 2016, p. 300–302.

- ^ a b Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 54; Calhoun 2005, p. 94.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Spetter, p. 301–302.

- ^ White, pp. 631–632.

- ^ Calhoun 1993, p. 661.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 49.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 46–49.

- ^ a b Calhoun 2005, pp. 100–104; Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 51–52.

- ^ a b c Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 51.

- ^ White, pp. 632–633.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Calhoun 2005, pp. 94–95.

- ^ a b c Calhoun 2005, pp. 94–95; Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 55–59.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 53.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 58; Calhoun 2005, p. 96.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 58–59; Calhoun 2005, p. 96.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 59.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 60.

- ^ a b Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 57–60.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 32.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 32–36.

- ^ Moore & Hale, pp. 83, 86.

- ^ a b Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 39–41.

- ^ a b c Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 36–37; Calhoun 2005, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Williams, p. 193.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 34–36.

- ^ Williams, pp. 193–194.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 61–65.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 65.

- ^ Calhoun 2005, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Wilson, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 65–67.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 67–69.

- ^ Calhoun 2005, pp. 89–90; Smith, p. 170.

- ^ Calhoun 2002, p. 253.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 75.

- ^ Calhoun 2005, pp. 107–109.

- ^ White, pp. 649–654.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 71.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 72.

- ^ Administrator, Joomla!. "President". www.presidentbenjaminharrison.org. Retrieved 2016-09-18.

- ^ a b Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 106.

- ^ a b April 16; Warren, 2021 | Louis S. "The Lakota Ghost Dance and the Massacre at Wounded Knee | American Experience | PBS". www.pbs.org. Retrieved 2021-07-21.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Military Buildup to Wounded Knee". History Nebraska. Retrieved 2021-07-21.

- ^ Moore & Hale, pp. 121–122; Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Moore & Hale, p. 121.

- ^ Landry, Alysa. "Benjamin Harrison: Busted Up Sioux Nation, No Remorse for Wounded Knee". Indian Country Today. Retrieved 2021-07-21.

- ^ Moore & Hale, pp. 121–122.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 92.

- ^ Calhoun 2005, pp. 112–114; Stuart, pp. 452–454.

- ^ White, pp. 637–639.

- ^ "President Benjamin Harrison". Vincent Voice Library. Archived from the original on October 15, 2007. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- ^ Moore & Hale, p. 96.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 95.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 97.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 95–96.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 96–97.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 102.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 103–108.

- President of the United States of America. Retrieved on 16 July 2017.at Wikisource

The full text of Executive Order 28

The full text of Executive Order 28 - ^ State and Union: Former resident says 'It was Weston Mills' and Westons Mills: ‘The way it should be’. Olean Times Herald. Retrieved March 20, 2016.

- Houghton Mifflin. pp. 342–344.

- ^ Milton Plesur, "America Looking Outward: The Years From Hayes to Harrison." The Historian 22.3 (1960): 280–295. Online

- ^ Calhoun 2005, pp. 119–121.

- ^ Calhoun 2005, pp. 74–76.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Moore & Hale, p. 108.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 117–120.

- ^ Allan B. Spetter, "Harrison and Blaine: No Reciprocity for Canada." Canadian Review of American Studies 12.2 (1981): 143–156.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 126–128.

- ISBN 9781851099511.

- ^ Noah Andre Trudeau, "'An Appalling Calamity'--In the teeth of the Great Samoan Typhoon of 1889, a standoff between the German and US navies suddenly didn't matter." Naval History Magazine 25.2 (2011): 54–59.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 114–116.

- ^ George Herbert Ryden, The Foreign Policy of the United States in Relation to Samoa (1933).

- ^ Walter LaFeber, The New Empire: An Interpretation of American Expansion, 1860–1898 (1963) pp 138–40, 323.

- ^ Paul M. Kennedy, The Samoan Tangle: A Study in Anglo-German-American Relations 1878–1900 (2013).

- ^ Uwe Spiekermann, "Dangerous Meat? German-American Quarrels Over Pork And Beef, 1870–1900" Bulletin of the GHI vol 46 (Spring 2010) online

- ^ Louis L. Snyder, "The American-German Pork Dispute, 1879–1891." Journal of Modern History 17.1 (1945): 16–28. online

- ^ John L. Gignilliat, "Pigs, Politics, and Protection: The European Boycott of American Pork, 1879–1891," Agricultural History 35.1 (1961): 3–12. online

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 131–136.

- ^ Suellen Hoy, and Walter Nugent. "Public health or protectionism? The German-American pork war, 1880–1891." Bulletin of the History of Medicine 63#2 (1989): 198–224. online

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 137–138.

- ^ Moore & Hale, pp. 135–136; Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 139–143.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 146.

- ^ Calhoun 2005, p. 127.

- ^ a b Calhoun 2005, pp. 128–129; Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 147–149.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 151.

- ^ Moore & Hale, p. 134.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 150–151.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 200–201.

- ^ Julius W. Pratt, "The Hawaiian Revolution: A Re-Interpretation." Pacific Historical Review 1.3 (1932): 273–294. online

- ^ George W. Baker, "Benjamin Harrison and Hawaiian Annexation: A Reinterpretation." Pacific Historical Review 33.3 (1964): 295–309. Online

- ^ LaFeber, The New Empire (1963)

- ^ a b Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 204–205.

- ^ Calhoun 2005, pp. 125–126.

- ^ Calhoun 2005, p. 132; Moore & Hale, p. 147.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 157.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 171.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 166.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 168.

- ^ Calhoun 2005, pp. 107, 126–127.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 81.

- ^ Calhoun 2005, pp. 134–137.

- ^ Calhoun 2005, pp. 138–139.

- ^ Calhoun 2005, pp. 140–141.

- ^ Calhoun 2005, pp. 147–150.

- ^ White, pp. 748–751.

- ^ White, pp. 752–754.

- ^ Calhoun 2005, p. 149.

- ^ Calhoun 2005, p. 156; Moore & Hale, pp. 143–145.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, pp. 198–199.

- ^ "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved February 22, 2008.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 199.

- ^ Socolofsky & Spetter, p. 200.

- ^ White, pp. 755–756.

- ^ White, p. 755.

- ^ Gerhardt, p. 141.

- ^ Amira, Dan (20 February 2012). "Let's Celebrate America's Most Forgotten President". New York. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- ^ Williams, p. 191.

- ^ Calhoun 2005, p. 6.

- ^ a b Onion, Rebecca (November 2, 2020). "What's the Worst a Vengeful Lame-Duck Administration Can Do?". Slate.

- ^ Boomhower 2019, p. 165.

- ^ a b Socolofsky & Spetter, p. x.

- ^ Glass, Andrew (August 20, 2017). "Benjamin Harrison born on Ohio farm, Aug. 20, 1833". Politico.

- ^ a b Cunningham, Lillian (June 12, 2016). "Benjamin Harrison, the first American president who tried to save a species". Washington Post.

- ^ U.S. News Staff (November 6, 2019). "Ranking America's Worst Presidents". U.S. News and World Report.

- ^ Rottinghaus, Brandon; Vaughn, Justin S. (19 February 2018). "How Does Trump Stack Up Against the Best — and Worst — Presidents?". New York Times. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- ^ "Presidential Historians Survey 2017". C-SPAN. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- ^ Fieldstadt, Elisha (September 12, 2022). "Presidents ranked from worst to best". CBS News.

- ^ Spetter, Allan B. (4 October 2016). "BENJAMIN HARRISON: IMPACT AND LEGACY". Miller Center. University of Virginia. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- ^ Charles Calhoun, Benjamin Harrison (2005).

- ^ Charles Calhoun, "Reimagining the "Lost Men" of the Gilded Age: Perspectives on the Late Nineteenth Century Presidents". Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era (2002) 1#3: 225–257.

- ^ a b Batten, p. 209

- ^ Jenkinson, Clay S. (March 26, 2023). "Good Government and the Road to Wounded Knee". Governing.

- ^ Bade, Rachael (June 28, 2010). "How Politics Led to Death at Wounded Knee". Roll Call.

Works cited

Books

- Boomhower, Ray E. (2019). Mr. President: A Life of Benjamin Harrison. Indiana Historical Society. ISBN 9780871954282.

- ISBN 978-0-8050-6952-5.

- Gerhardt, Michael J. (2013). The Forgotten Presidents: Their Untold Constitutional Legacy. OUP USA. ISBN 9780199967797.

- Moore, Chieko; Hale, Hester Anne (2006). Benjamin Harrison: Centennial President. Nova Publishers. ISBN 978-1-60021-066-2.

- Smith, Robert C., ed. (2003). Encyclopedia of African-American politics. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8160-4475-7.

- Socolofsky, Homer E.; Spetter, Allan B. (1987). The Presidency of Benjamin Harrison. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0320-6.

- Spetter, Allan B. (2016). "Benjamin Harrison". In Gormley, Ken (ed.). The Presidents and the Constitution: A Living History. New York: New York University Press Press. ISBN 9781479839902.

- Wallace, Lew (1888). Life and Public Services of Benjamin Harrison. Edgewood Publishing Co.

- ISBN 9780190619060.

- Williams, R. Hal (1974). "Benjamin Harrison 1889–1893". In Woodward, C. Vann (ed.). Responses of the Presidents to the Charges of Misconduct. Dell Publishing Co., Inc. pp. 191–195. ISBN 0-440-05923-2.

- Wilson, Kirt H. (2005). "The Politics of Place and Presidential Rhetoric in the United States, 1875–1901". In Rigsby, Enrique D.; Aune, James Arnt (eds.). Civil Rights Rhetoric and the American Presidency. TAMU Press. pp. 16–40. ISBN 978-1-58544-440-3.

Articles

- Batten, Donna, ed. (2010). "Gale Encyclopedia of American Law". 5 (3 ed.). Detroit: 208–209.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

- Calhoun, Charles W. (Fall 1993). "Civil Religion and the Gilded Age Presidency: The Case of Benjamin Harrison". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 23 (4): 651–667. JSTOR 27551144.

- Calhoun, Charles W. (July 2002). "Reimagining the "Lost Men" of the Gilded Age: Perspectives on the Late Nineteenth Century Presidents". The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. 1 (3): 225–257. S2CID 162509769.

- Gallagher, Douglas Steven. "The 'smallest mistake': explaining the failures of the Hayes and Harrison presidencies." White House Studies 2.4 (2002): 395–414.

- Graff, Henry F., ed. The Presidents: A Reference History (3rd ed. 2002) online

- Spetter, Allan. "Harrison and Blaine: Foreign Policy, 1889–1893" Indiana Magazine of History 65#3 (1969), pp. 214–227 online

- Stuart, Paul (September 1977). "United States Indian Policy: From the Dawes Act to the American Indian Policy Review Commission". Social Service Review. 51 (3): 451–463. S2CID 143506388.

- Volwiler, A. T. "Harrison, Blaine, and American Foreign Policy, 1889-1893" Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 79#4 1938) pp. 637–648 online

Further reading

- Baker, George W. "Benjamin Harrison and Hawaiian Annexation: A Reinterpretation." Pacific Historical Review 33.3 (1964): 295–309. online

- Calhoun, Charles W. "Benjamin Harrison, Centennial President: A Review Essay." Indiana Magazine of History (1988). online

- Dozer, Donald Marquand. "Benjamin Harrison and the Presidential Campaign of 1892." American Historical Review 54.1 (1948): 49–77. online

- Gunderson, Megan M. Benjamin Harrison (2009) for middle schools

- Holbrook, Francis X., and John Nikol. "Chilean Crisis of 1891–1892." American Neptune 38.4 (1978): 291–300.

- Rhodes, James Ford. History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850: 1877–1896 (1919) online complete; old, factual and heavily political, by winner of Pulitzer Prize

- Ringenberg, William C. "Benjamin Harrison: The Religious Thought and Practice of a Presbyterian President." American Presbyterians 64.3 (1986): 175–189. online

- Sievers, Harry Joseph. Benjamin Harrison, Hoosier president: The White House and after (1968), vol 3 of his thin but scholarly biography

- Sinkler, George. "Benjamin Harrison and the Matter of Race." Indiana Magazine of History (1969): 197–213. online

- Socolofsky, Homer E. "Benjamin Harrison and the American west." Great Plains Quarterly (1985): 249–258. online

- Taylor, Mark Zachary. "Ideas and Their Consequences: Benjamin Harrison and the Seeds of Economic Crisis, 1889–1893." Critical Review 33.1 (2021): 102–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/08913811.2020.1881354

- Wilson, Kirtley Hasketh. "The problem with public memory: Benjamin Harrison confronts the 'southern question'." in Before the rhetorical presidency (Texas A&M University Press, 2008) pp. 267–288.

Primary sources

- Harrison, Benjamin. Public papers and addresses of Benjamin Harrison, twenty-third President of the United States, March 4, 1889, to March 4, 1893. (1893). online

- Harrison, Benjamin. Speeches of Benjamin Harrison, Twenty-third President of the United States (DigiCat, 2022) online

- Volwiler, Albert T., ed. The Correspondence between Benjamin Harrison and James G. Blaine, 1882–1893 (1940)

External links

- Miller Center on the Presidency at U of Virginia, brief articles on Harrison and his presidency