Primidone

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Lepsiral, Mysoline, Resimatil, others |

| Other names | desoxyphenobarbital, desoxyphenobarbitone |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682023 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | Anticonvulsant, barbiturate |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | ~100%[4] |

| Protein binding | 25%[4] |

| Metabolism | Liver |

| Elimination half-life | Primidone: 5-18 h, Phenobarbital: 75-120 h,[4] PEMA: 16 h[5] Time to reach steady state: Primidone: 2-3 days, Phenobarbital&PEMA 1-4weeks[6] |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Primidone, sold under various brand names, is a

Its common side effects include sleepiness, poor coordination, nausea, and loss of appetite.[7] Severe side effects may include suicide and psychosis. [8][7] Use during pregnancy may result in harm to the fetus.[9] Primidone is an anticonvulsant of the barbiturate class;[7] however, its long-term effect in raising the seizure threshold is likely due to its active metabolite, phenobarbital.[10]

Primidone was approved for medical use in the United States in 1954.

Medical uses

Epilepsy

It is licensed for generalized tonic-clonic and complex partial seizures in the United Kingdom.[13] In the United States, primidone is approved for adjunctive (in combination with other drugs) and monotherapy (by itself) use in generalized tonic-clonic seizures, simple partial seizures, complex partial seizures, and myoclonic seizures.[13] In juvenile myoclonic epilepsy, it is a second-line therapy, reserved for when the valproates or lamotrigine do not work and when the other second-line therapy, acetazolamide, does not work.[14]

Open-label case series have suggested that primidone is effective in the treatment of epilepsy.

Essential tremor

Primidone is considered to be a first-line therapy for essential tremor, along with propranolol. In tremor amplitude reduction, it is just as effective as propranolol, reducing it by 50%. Both drugs are well studied for this condition, unlike other therapies, and are recommended for initial treatment. A low-dose therapy (250 mg/day) is just as good as a high-dose therapy (750 mg/day).[21]

Primidone is not the only anticonvulsant used for essential tremor; the others include

Psychiatric disorders

In 1965, Monroe and Wise reported using primidone along with a

In March 1993, S.G. Hayes of the University of Southern California School of Medicine reported that 9 out of 27 people (33%) with either treatment-resistant depression or treatment-resistant bipolar disorder had a permanent positive response to primidone. A plurality of subjects was also given methylphenobarbital in addition to or instead of primidone.[24]

Adverse effects

This article needs more primary sources. (February 2018) |  |

Primidone can cause drowsiness, listlessness,

Primidone has other cardiovascular effects in beyond shortening the QT interval. Both phenobarbital and it are associated with elevated serum levels (both fasting and six hours after

It was first reported to exacerbate hepatic

Less than 1% of primidone users experience a rash. Compared to carbamazepine, lamotrigine, and phenytoin, this is very low. The rate is comparable to that of felbamate, vigabatrin, and topiramate.

Primidone, along with phenytoin and phenobarbital, is one of the anticonvulsants most heavily associated with bone diseases such as osteoporosis, osteopenia (which can precede osteoporosis), osteomalacia, and fractures.[32][33][34] The populations usually said to be most at risk are institutionalized people, postmenopausal women, older men, people taking more than one anticonvulsant, and children, who are also at risk of rickets.[32] Bone demineralization is suggested to be most pronounced in young people (25–44 years of age),[33] and one 1987 study of institutionalized people found that the rate of osteomalacia in the ones taking anticonvulsants—one out of 19 individuals taking an anticonvulsant (vs. none among the 37 people taking none) —was similar to that expected in elderly people. The authors speculated that this was due to improvements in diet, sun exposure, and exercise in response to earlier findings, and/or that this was because it was sunnier in London than in the Northern European countries, which had earlier reported this effect.[34] In any case, the use of more than one anticonvulsant has been associated with an increased prevalence of bone disease in institutionalized epilepsy patients versus institutionalized people who did not have epilepsy. Likewise, postmenopausal women taking anticonvulsants have a greater risk of fracture than their drug-naive counterparts.[32]

Anticonvulsants affect the bones in many ways. They cause hypophosphatemia, hypocalcemia, low vitamin D levels, and increased parathyroid hormone. Anticonvulsants also contribute to the increased rate of fractures by causing somnolence, ataxia, and tremor, which would cause gait disturbance, further increasing the risk of fractures on top of the increase due to seizures and the restrictions on activity placed on epileptic people. Increased fracture rate has also been reported for carbamazepine, valproate, and clonazepam. The risk of fractures is higher for people taking enzyme-inducing anticonvulsants than for people taking enzyme-non-inducing anticonvulsants.[33] In addition to all of the above, primidone can cause arthralgia.[25]

This antagonistic effect is not due to the inhibition of

In addition to increasing the risk of megaloblastic anemia, primidone, like other older anticonvulsants, also increases the risk of neural tube defects,[39] and like other enzyme-inducing anticonvulsants, it increases the likelihood of cardiovascular defects, and cleft lip without cleft palate.[9] Epileptic women are generally advised to take folic acid,[39] but there is conflicting evidence regarding the effectiveness of vitamin supplementation in the prevention of such defects.[9][40]

Additionally, a coagulation defect resembling vitamin K deficiency has been observed in newborns of mothers taking primidone.[39] Because of this, primidone is a Category D medication.[41]

Primidone, like phenobarbital and the benzodiazepines, can also cause sedation in the newborn and also withdrawal within the first few days of life; phenobarbital is the most likely out of all of them to do that.[39]

In May 2005, Dr. M. Lopez-Gomez's team reported an association between the use of primidone and depression in epilepsy patients; this same study reported that inadequate seizure control, post-traumatic epilepsy, and polytherapy were also risk factors. Polytherapy was also associated with poor seizure control. Of all of the risk factors, use of primidone and inadequate seizure control were the greatest, with

Primidone is one of the anticonvulsants associated with anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syndrome, with the others being carbamazepine, phenytoin, and phenobarbital. This syndrome consists of fever, rash, peripheral leukocytosis, lymphadenopathy, and occasionally hepatic necrosis.[47]

Overdose

The most common symptoms of primidone overdose are coma with loss of

In the Netherlands alone, 34 cases of suspected primidone poisoning occurred between 1978 and 1982. Of these, primidone poisoning was much less common than phenobarbital poisoning; 27 of those adult cases were reported to the Dutch National Poison Control Center. Of these, one person taking it with phenytoin and phenobarbital died, 12 became drowsy, and four were comatose.[52]

Treatments for primidone overdose have included

In the three adults who are reported to have succumbed, the doses were 20–30 g.[50][55][56] However, two adult survivors ingested 30 g[50] 25 g,[55] and 22.5 g.[51] One woman experienced symptoms of primidone intoxication after ingesting 750 mg of her roommate's primidone.[57]

Interactions

Taking primidone with monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) such as isocarboxazid (Marplan), phenelzine (Nardil), procarbazine (Matulane), selegiline (Eldepryl), tranylcypromine (Parnate) or within two weeks of stopping any one of them may potentiate the effects of primidone or change one's seizure patterns.[58] Isoniazid, an antitubercular agent with MAOI properties, has been known to strongly inhibit the metabolism of primidone.[59]

Like many anticonvulsants, primidone interacts with other anticonvulsants. Clobazam decreases clearance of primidone,[60]

Primidone and the other enzyme-inducing anticonvulsants can cut the half-life of

Mechanism of action

The exact mechanism of primidone's anticonvulsant action is still unknown after over 50 years.

Pharmacokinetics

Primidone converts to phenobarbital and PEMA;[73] it is still unknown which exact cytochrome P450 enzymes are responsible.[59] The phenobarbital, in turn, is metabolized to p-hydroxyphenobarbital.[74] The rate of primidone metabolism was greatly accelerated by phenobarbital pretreatment, moderately accelerated by primidone pretreatment, and reduced by PEMA pretreatment.[75] In 1983, a new minor metabolite, p-hydroxyprimidone, was discovered.[76]

Primidone, carbamazepine, phenobarbital, and phenytoin are among the most potent hepatic enzyme-inducing drugs in existence, which occurs at therapeutic doses. In fact, people taking these drugs have displayed the highest degree of hepatic-enzyme induction on record.[65] In addition to being an inducer of CYP3A4, it is also an inducer of CYP1A2, which causes it to interact with substrates such as fluvoxamine, clozapine, olanzapine, and tricyclic antidepressants, as well as potentially increasing the toxicity of tobacco products. Its metabolite, phenobarbital, is a substrate of CYP2C9,[64] CYP2B6,[77] CYP2C8, CYP2C19, CYP2A6, CYP3A5,[78] CYP1E1, and the CYP2E subfamily.[79] The gene expression of these isoenzymes is regulated by human pregnane receptor X (PXR) and constitutive androstane receptor (CAR). Phenobarbital induction of CYP2B6 is mediated by both.[78][80] Primidone does not activate PXR.[81]

The rate of metabolism of primidone into phenobarbital was

The percentage of primidone converted to phenobarbital has been estimated to be 5% in dogs and 15% in humans. Work done 12 years later found that the serum phenobarbital 0.111 mg/100 mL for every mg/kg of primidone ingested. Authors publishing a year earlier estimated that 24.5% of primidone was metabolized to phenobarbital, but the patient reported by Kappy and Buckley would have had a serum level of 44.4 mg/100 mL instead of 8.5 mg/100 mL if this were true for individuals who have ingested a large dose. The patient reported by Morley and Wynne would have had serum barbiturate levels of 50 mg/100 mL, which would have been fatal.[50]

History

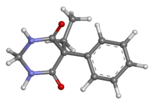

Primidone is a congener of phenobarbital, where the carbonyl oxygen of the urea moiety is replaced by two hydrogen atoms.[84] The effectiveness of Primidone for epilepsy was first demonstrated in 1949 by Yule Bogue.[15] He found it to have a similar anticonvulsant effect, but more specific, i.e. with fewer associated sedative effects.[85]

It was brought to market a year later by the Imperial Chemical Industry, now known as AstraZeneca in the United Kingdom[55][86] and Germany.[56] In 1952, it was approved in the Netherlands.[52]

Also in 1952, Drs. Handley and Stewart demonstrated its effectiveness in the treatment of patients who failed to respond to other therapies; it was noted to be more effective in people with idiopathic generalized epilepsy than in people whose epilepsy had a known cause.[15] Dr. Whitty noted in 1953 that it benefitted patients with psychomotor epilepsy, who were often treatment-resistant. Toxic effects were reported to be mild.[16] That same year, it was approved in France.[87] Primidone was introduced in 1954 under the brandname Mysoline by Wyeth in the United States.[88]

Association with megaloblastic anemia

In 1954, Chalmers and Boheimer reported that the drug was associated with megaloblastic anemia.[89] Between 1954 and 1957, 21 cases of megaloblastic anemia associated with primidone and/or phenytoin were reported.[90] In most of these cases, the anemia was due to vitamin deficiencies - usually folic acid deficiency, in one case vitamin B12 deficiency,[89] and in one case vitamin C deficiency.[90] Some cases were associated with deficient diets - one patient ate mostly bread and butter,[89] another ate bread, buns, and hard candy, and another could rarely be persuaded to eat in the hospital.[90]

The idea that folic acid deficiency could cause megaloblastic anemia was not new. What was new was the idea that drugs could cause this in well-nourished people with no intestinal abnormalities.[89] In many cases, it was not clear which drug had caused it.[91] This might be related to the structural similarity between folic acid, phenytoin, phenobarbital, and primidone.[92] Folic acid had been found to alleviate the symptoms of megaloblastic anemia in the 1940s, not long after it was discovered, but the typical patient only made a full recovery—cessation of CNS and PNS symptoms as well as anemia—on B12 therapy.[93] Five years earlier, folic acid deficiency was linked to birth defects in rats.[94] Primidone was seen by some as too valuable to withhold based on the slight possibility of this rare side effect[89] and by others as dangerous enough to be withheld unless phenobarbital or some other barbiturate failed to work for this and other reasons (i.e., reports of permanent psychosis).[95]

Available forms

Primidone is available as a 250 mg/5mL suspension, and in the form of 50 mg, 125 mg, and 250 mg tablets. It is also available in a chewable tablet formulation in Canada.[96]

It is marketed as several different brands, including Mysoline (Canada,

Veterinary uses

Primidone has veterinary uses, including the prevention of

References

- ^ "Primidone (Mysoline) Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 18 February 2019. Archived from the original on 26 November 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ Anvisa (31 March 2023). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 4 April 2023). Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ "Primidone SERB 50mg Tablets - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 18 August 2014. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- ^ a b c Ochoa JG, Riche W, Passaro EA (2005). Talavera F, Cavazos JE, Benbadis SR (eds.). "Antiepileptic Drugs: An Overview". eMedicine. eMedicine, Inc. Archived from the original on 8 February 2012. Retrieved 2 July 2005.

- ^ CDER, U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES (2003–2005). "Primidone (Mysoline)". Pharmacology Guide for Brain Injury Treatment. Brain Injury Resource Foundation. Archived from the original on 17 March 2010. Retrieved 2 July 2005.

- ^ Yale Medical School, Department of Laboratory Medicine (1998). "Therapeutic Drug Levels". YNHH Laboratory Manual - Reference Documents. Yale Medical School. Archived from the original on 20 February 2009. Retrieved 13 July 2005.

- ^ a b c d e f "Primidone Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 29 June 2019. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

- ^ ISBN 9780857113382.

- ^ PMID 11096168.

- Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (7th ed.). New York: Macmillan.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2020". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 18 March 2020. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ "Primidone - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 11 April 2020. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ a b Acorus Therapeutics, Ltd. (2005). "Mysoline 250 mg Tablets". electronic Medicines Compendium. Datapharm Communications and the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI). Archived from the original on 16 March 2008. Retrieved 8 March 2006.

- ^ Broadley MA (200). "Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy of Janz (JME)". The Childhood Seizure e-Book. Valhalla, New York. Archived from the original on 7 June 2005. Retrieved 3 July 2005.

- ^ PMID 13359420.

- ^ PMID 13082031.

- PMID 13288784.

- PMID 13042720.

- PMID 6481545.

- ^ S2CID 42871014.

- ^ PMID 15972843.

- PMID 5320821.

- S2CID 26067790.

- PMID 8348197.

- ^ a b c d e "Summary of Product Characteristics" (PDF). Official Acorus Therapeutics Site. Acorus Therapeutics. 1 June 2007. pp. 3–4. Retrieved 12 October 2007. [dead link]

- ^ PMID 3925335.

- ^ PMID 15998816.

- PMID 932769.

- S2CID 42052760.

- S2CID 40044726.

- S2CID 32556955. Archived from the originalon 9 September 2009. Retrieved 25 September 2007.

- ^ S2CID 24519673.

- ^ PMID 16956398.

- ^ PMID 3656313.

- ^ "Mysoline". RxList. p. 3. Archived from the original on 31 March 2007. Retrieved 11 March 2007.

- ^ Nagalla S, Schick P, Davis TH (2005). Talavera F, Sacher RA, Besa EC (eds.). "Megaloblastic Anemia". eMedicine. Archived from the original on 18 August 2005. Retrieved 15 August 2005.

- PMID 5835440.

- S2CID 28324730.

- ^ PMID 15879038.

- PMID 6519344.

- S2CID 22277001.

- S2CID 23642891.

- PMID 10440522.

- S2CID 31753372.

- S2CID 23611090.

- S2CID 35158990.

- S2CID 38661360.

- S2CID 13243424.

- PMID 4959849.

- ^ PMID 5779436.

- ^ PMID 4812959.

- ^ PMID 6655772.

- ^ PMID 4642162.

- S2CID 30289848.

- ^ PMID 13446511.

- ^ S2CID 35210736.

- PMID 5919666.

- ^ a b "Primidone". The Merck Manual's Online Medical Library. Lexi-Comp. Archived from the original on 28 October 2010. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ PMID 11158730.

- S2CID 12698316.

- S2CID 73163592.

- S2CID 22081046.

- ^ GlaxoSmithKline (2005). "LAMICTAL Prescribing Information" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 September 2006. Retrieved 14 March 2006.

- ^ S2CID 30800986.

- ^ PMID 6435654.

- S2CID 39118343.

- PMID 2108815.

- ^ "Mysoline: Clinical Pharmacology". RxList. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 7 October 2007.

- S2CID 22628709.

- PMID 7031184.

- PMID 28106668.

- PMID 33853504.

- ISBN 978-0-7484-0864-1.

- PMID 7380904. Archived from the originalon 2 June 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2005.

- PMID 1151744.

- PMID 6140148. Archived from the originalon 26 February 2009. Retrieved 3 August 2005.

- PMID 16751792.

- ^ PMID 17827782. Archived from the originalon 20 February 2009. Retrieved 7 October 2007.

- PMID 12642468.

- PMID 17904175.

- S2CID 35103040.

- PMID 6845402.

- PMID 2291873.

- ^ Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 1964. p. 226.

- PMID 13066728.

- PMID 13383203.

- S2CID 29638422.

- ^ Wyeth. "Wyeth Timeline". About Wyeth. Archived from the original on 7 January 2009. Retrieved 11 November 2007.

- ^ PMID 13403983.

- ^ PMID 13472024.

- PMID 13304415.

- PMID 13276653.

- PMID 20278334.

- PMID 13000492.

- PMID 13465742.

- ^ a b Schachter SC (February 2004). "Mysoline". Epilepsy.com. Epilepsy Therapy Development Project. Archived from the original on 6 October 2008. Retrieved 10 January 2007.

- ^ a b "Valeant Pharmaceuticals International: Products". Archived from the original on 1 June 2005. Retrieved 3 July 2005.

- ^ "Service List". Archived from the original on 15 May 2006. Retrieved 13 March 2006.

- ^ Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma (2005). "Primidone 250 mg Tablets & Primidone 99.5% Powder" (PDF). Retrieved 13 March 2006.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Acorus Therapeutics Ltd. - Ordering - UK". acorus-therapeutics.com. Acorus Therapeutics. Archived from the original on 7 April 2005. Retrieved 4 July 2005.

- ^ "Emre Ecza - History".

MYSOLINE tablet ( primidone ) is a registered product of our company in Turkey...

- ^ "Prysoline Tablets". The Israel Drug Registry. The State of Israel. 2005. Archived from the original on 2 October 2011. Retrieved 17 February 2006.

- ^ "APO-PRIMIDONE". Apotex. 10 January 2007. Archived from the original on 6 October 2008. Retrieved 10 January 2007.

- ^ "Liskantin". Desitin. Archived from the original on 22 August 2005. Retrieved 3 July 2005.

- ^ "Resimatil Tabletten". Deutsche Krankenversicherung AG. Retrieved 3 July 2005.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Mylepsinum Tabletten". Deutsche Krankenversicherung AG. Retrieved 3 July 2005.[permanent dead link]

- ^ National Office of Animal Health. "Compendium of Veterinary Medicine". Archived from the original on 6 October 2007. Retrieved 19 March 2007.

- ^ The Pig Site. "Savaging of Piglets". Archived from the original on 24 November 2006. Retrieved 19 March 2007.

Further reading

- "Toxicology and Carcinogenesis Studies of Primidone in F344/N Rats and B6C3F1 Mice (Feed Studies)" (PDF). Department of Health and Human Services National Toxicology Program. September 2000.

- Lay summary in: "Abstract for TR-476". National Toxicology Program. September 2000.

External links

- "Testing Status of Primidone (primaclone) 10270-A". National Toxicology Program.