Kingdom of Mysore

Kingdom of Mysore | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1399–1950 | |||||||||

| Anthem: "ಕಾಯೌ ಶ್ರೀ ಗೌರಿ" "Kayou Sri Gowri" (1868–1950) (English: "Great Gowri") | |||||||||

The Kingdom of Mysore during the reign of Tipu Sultan, 1784 AD (at its greatest extent) | |||||||||

| Status | Kingdom (Subordinate to Vijayanagara Empire until 1565) under a subsidiary alliance with the British Crown from 1799 Princely state under the British Crown from 1831 | ||||||||

| Capital | Mysore, Srirangapatna | ||||||||

| Official languages | Kannada, Persian | ||||||||

| Religion | Hinduism, Islam | ||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Mysoreans | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Maharaja | |||||||||

• 1399–1423 (first) | Yaduraya Wodeyar | ||||||||

• 1940–1950 (last) | Jayachamaraja Wodeyar | ||||||||

Diwan | |||||||||

• 1782–1811 (first) | Purnaiah | ||||||||

• 1946–1949 (last) | Arcot Ramasamy Mudaliar | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | 1399 | ||||||||

• Earliest records | 1551 | ||||||||

• Maratha–Mysore War | 1759–1787 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1950 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | India | ||||||||

The Kingdom of Mysore was a realm in the southern part of

The kingdom, which was founded and ruled for the most part by the Hindu

During this time, it came into conflict with the

Even as a princely state, Mysore came to be counted among the more developed and urbanised regions of South Asia. This period (1799–1947) also saw Mysore emerge as one of the important centres of art and culture in India. The Mysore kings were not only accomplished exponents of the fine arts and men of letters, they were enthusiastic patrons as well. Their legacies continue to influence music and the arts even today, as well as rocket science with the use of Mysorean rockets.[5]

History

Early history

Sources for the history of the kingdom include numerous extant

Autonomy: advances and reversals

The kings who followed ruled as vassals of the Vijayanagara Empire until the decline of the latter in 1565. By this time, the kingdom had expanded to thirty-three villages protected by a force of 300 soldiers.[16] King Timmaraja II conquered some surrounding chiefdoms,[17] and King Bola Chamaraja IV (lit, "Bald"), the first ruler of any political significance among them, withheld tribute to the nominal Vijayanagara monarch Aravidu Ramaraya.[18] After the death of Aravidu Ramaraya, the Wodeyars began to assert themselves further and King Raja Wodeyar I wrested control of Srirangapatna from the Vijayanagara governor (Mahamandaleshvara) Aravidu Tirumalla – a development which elicited, if only ex post facto, the tacit approval of Venkatapati Raya, the incumbent king of the diminished Vijayanagar Empire ruling from Chandragiri.[19] Raja Wodeyar I's reign also saw territorial expansion with the annexation of Channapatna to the north from Jaggadeva Raya[19][20] – a development which made Mysore a regional political factor to reckon with.[21][22]

Consequently, by 1612–13, the Wodeyars exercised a great deal of autonomy and even though they acknowledged the nominal overlordship of the

Nevertheless, from around 1704, when the kingdom passed on to the "Mute king" (Mukarasu)

Under Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan

By 1761, Maratha power had diminished and by 1763, Hyder Ali had captured the Keladi kingdom, defeated the rulers of

In a bid to stem Hyder's rise, the British allied with the Marathas and the Nizam of

By 1779, Hyder Ali had captured parts of modern Tamil Nadu and

By 1783 neither the British nor Mysore were able to obtain a clear overall victory. The French withdrew their support of Mysore following the

Tipu's

Princely state

Following Tipu's fall, a part of the kingdom of Mysore was annexed and divided between the Madras Presidency and the

The years that followed witnessed cordial relations between Mysore and the British until things began to sour in the 1820s. Even though the Governor of Madras, Thomas Munro, determined after a personal investigation in 1825 that there was no substance to the allegations of financial impropriety made by A. H. Cole, the incumbent Resident of Mysore, the Nagar revolt (a civil insurrection) which broke out towards the end of the decade changed things considerably. In 1831, close on the heels of the insurrection and citing mal-administration, the British took direct control of the princely state, placing it under a commission rule.[60][61] For the next fifty years, Mysore passed under the rule of successive British Commissioners; Sir Mark Cubbon, renowned for his statesmanship, served from 1834 until 1861 and put into place an efficient and successful administrative system which left Mysore a well-developed state.[62]

In 1876–77, however, towards the end of the period of direct British rule, Mysore was struck by a devastating famine with estimated mortality figures ranging between 700,000 and 1,100,000, or nearly a fifth of the population.[63] Shortly thereafter, Maharaja Chamaraja X, educated in the British system, took over the rule of Mysore in 1881, following the success of a lobby set up by the Wodeyar dynasty that was in favour of rendition. Accordingly, a resident British officer was appointed at the Mysore court and a Diwan to handle the Maharaja's administration.[64] From then onwards, until Indian independence in 1947, Mysore remained a Princely State within the British Indian Empire, with the Wodeyars continuing their rule.[64]

After the demise of Maharaja Chamaraja X,

Administration

| Feudatory Monarchy (As vassals of Vijayanagara Empire) (1399–1553) | |

|---|---|

| Yaduraya Wodeyar | 1399–1423 |

| Chamaraja Wodeyar I | 1423–1459 |

| Timmaraja Wodeyar I | 1459–1478 |

| Chamaraja Wodeyar II | 1478–1513 |

| Chamaraja Wodeyar III | 1513–1553 |

| Absolute Monarchy (Independent Wodeyar Kings) (1553–1761)

| |

| Timmaraja Wodeyar II | 1553–1572 |

| Chamaraja Wodeyar IV | 1572–1576 |

| Chamaraja Wodeyar V | 1576–1578 |

| Raja Wodeyar I | 1578–1617 |

| Chamaraja Wodeyar VI | 1617–1637 |

| Raja Wodeyar II | 1637–1638 |

| Narasaraja Wodeyar I | 1638–1659 |

| Dodda Devaraja Wodeyar | 1659–1673 |

| Chikka Devaraja Wodeyar | 1673–1704 |

Narasaraja Wodeyar II

|

1704–1714 |

Krishnaraja Wodeyar I

|

1714–1732 |

| Chamaraja Wodeyar VII | 1732–1734 |

Krishnaraja Wodeyar II

|

1734–1761 |

| Puppet Monarchy (Under Tipu Sultan ) (1761–1799)

| |

Krishnaraja Wodeyar II

|

1761–1766 |

| Nanjaraja Wodeyar | 1766–1770 |

| Chamaraja Wodeyar VIII | 1770–1776 |

| Chamaraja Wodeyar IX | 1776–1796 |

| Puppet Monarchy (Under British Rule) (1799–1831) | |

Krishnaraja Wodeyar III

|

1799–1831 |

| Titular Monarchy (Monarchy abolished) (1831–1881) | |

Krishnaraja Wodeyar III

|

1831–1868 |

| Chamarajendra Wadiyar X | 1868–1881 |

| Constitutional Monarchy (under British Crown ) Monarchy restored by Rendition Act 1881 (1881–1947)

| |

| Chamarajendra Wadiyar X | 1881–1894 |

| Krishnaraja Wadiyar IV | 1894–1940 |

Jayachamaraja Wadiyar

|

1940–1947 |

| Constitutional Monarchy (Mysore State, Dominion of India) (1947–1956) | |

Jayachamaraja Wadiyar (as Rajpramukh )

|

1947–1956 |

| Titular Monarchy (Monarchy abolished) (1956–present) | |

Jayachamaraja Wadiyar

|

1956–1974 |

| Srikantadatta Wadiyar | 1974–2013 |

| Yaduveera Chamaraja Wadiyar | 2015–present |

There are no records relating to the administration of the Mysore territory during the

The rule of Chikka Devaraja saw several reforms effected. Internal administration was remodelled to suit the kingdom's growing needs and became more efficient. A postal system came into being. Far-reaching financial reforms were also introduced. Several petty taxes were imposed in place of direct taxes, as a result of which the peasants were compelled to pay more by way of land tax.[73] The king is said to have taken a personal interest in the regular collection of revenues the treasury burgeoned to 90,000,000 Pagoda (a unit of currency) – earning him the epithet "Nine crore Narayana" (Navakoti Narayana). In 1700, he sent an embassy to Aurangazeb's court bestowed upon him the title Jug Deo Raja and awarded permission to sit on the ivory throne. Following this, he founded the district offices (Attara Kacheri), the central secretariat comprising eighteen departments, and his administration was modelled on Mughal lines.[74]

During

When the

After the rendition,

Sir

In 1939

Economy

The vast majority of the people lived in villages and agriculture was their main occupation. The economy of the kingdom was based on agriculture. Grains, pulses, vegetables and flowers were cultivated. Commercial crops included sugarcane and cotton. The agrarian population consisted of landlords (

Under Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan

Tipu Sultan is credited with founding state trading depots in various locations of his kingdom. In addition, he founded depots in foreign locations such as

The

Under British rule

This system changed under the subsidiary alliance with the British, when tax payments were made in cash and were used for the maintenance of the army, police and other civil and public establishments. A portion of the tax was transferred to England as the "Indian tribute".[94] Unhappy with the loss of their traditional revenue system and the problems they faced, peasants rose in rebellion in many parts of south India.[95] After 1800, the Cornwallis land reforms came into effect. Reade, Munro, Graham and Thackeray were some administrators who improved the economic conditions of the masses.[96] However, the homespun textile industry suffered while most of India was under British rule, except the producers of the finest cloth and the coarse cloth which was popular with the rural masses. This was due to the manufacturing mills of Manchester, Liverpool and Scotland being more than a match for the traditional handweaving industry, especially in spinning and weaving.[97][98]

The economic revolution in England and the tariff policies of the British also caused massive de-industrialization in other sectors throughout British India and Mysore. For example, the gunny bag weaving business had been a monopoly of the Goniga people, which they lost when the British began ruling the area. The import of a chemical substitute for saltpetre (potassium nitrate) affected the Uppar community, the traditional makers of saltpetre for use in gunpowder. The import of kerosene affected the Ganiga community which supplied oils. Foreign enamel and crockery industries affected the native pottery business, and mill-made blankets replaced the country-made blankets called kambli.[99] This economic fallout led to the formation of community-based social welfare organisations to help those within the community to cope better with their new economic situation, including youth hostels for students seeking education and shelter.[100] However, the British economic policies created a class structure consisting of a newly established middle class comprising various blue and white-collared occupational groups, including agents, brokers, lawyers, teachers, civil servants and physicians. Due to a more flexible caste hierarchy, the middle class contained a heterogeneous mix of people from different castes.[101]

Culture

Religion

The early kings of the Wodeyar dynasty worshipped the Hindu god Shiva. The later kings, starting from the 17th century, took to

The contact between South India and

Society

Before the 18th century, the society of the kingdom followed age-old and deeply established norms of social interaction between people. Accounts by contemporaneous travellers indicate the widespread practice of the

With the advent of British power, English education gained prominence in addition to traditional education in local languages. These changes were orchestrated by

Social reforms aimed at removing practices such as

Literature

The era of the Kingdom of Mysore is considered a golden age in the development of Kannada literature. Not only was the Mysore court adorned by famous Brahmin and Veerashaiva writers and composers,[111][131] the kings themselves were accomplished in the fine arts and made important contributions.[132][133] While conventional literature in philosophy and religion remained popular, writings in new genres such as chronicle, biography, history, encyclopaedia, novel, drama, and musical treatise became popular.[134] A native form of folk literature with dramatic representation called Yakshagana gained popularity.[135][136] A remarkable development of the later period was the influence of English literature and classical Sanskrit literature on Kannada.[137]

Govinda Vaidya, a native of Srirangapatna, wrote Kanthirava Narasaraja Vijaya, a eulogy of his patron King Narasaraja I. Written in sangatya metre (a composition meant to be rendered to the accompaniment of a musical instrument), the book describes the king's court, popular music and the types of musical compositions of the age in twenty-six chapters.[138][139] King Chikka Devaraja was the earliest composer of the dynasty.[31][140] To him is ascribed the famous treatise on music called Geetha Gopala. Though inspired by Jayadeva's Sanskrit work Geetha Govinda, it had an originality of its own and was written in saptapadi metre.[141] Contemporary poets who left their mark on the entire Kannada-speaking region include the Brahmin poet Lakshmisa and the itinerant Veerashaiva poet Sarvajna. Female poets also played a role in literary developments, with Cheluvambe (the queen of Krishnaraja Wodeyar I), Helavanakatte Giriyamma, Sri Rangamma (1685) and Sanchi Honnamma (Hadibadeya Dharma, late 17th century) writing notable works.[142][143]

A polyglot, King Narasaraja II authored fourteen Yakshaganas in various languages, though all are written in Kannada script.[144] Maharaja Krishnaraja III was a prolific writer in Kannada for which he earned the honorific Abhinava Bhoja (a comparison to the medieval King Bhoja).[145] Over forty writings are attributed to him, of which the musical treatise Sri Tatwanidhi and a poetical romance called Saugandika Parinaya written in two versions, a sangatya and a drama, are most well known.[146] Under the patronage of the Maharaja, Kannada literature began its slow and gradual change towards modernity. Kempu Narayana's Mudramanjusha ("The Seal Casket", 1823) is the earliest work that has touches of modern prose.[147] However, the turning point came with the historically important Adbhuta Ramayana (1895) and Ramaswamedham (1898) by Muddanna, whom the Kannada scholar Narasimha Murthy considers "a Janus like figure" of modern Kannada literature. Muddanna has deftly handled an ancient epic from an entirely modern viewpoint.[148]

Basavappa Shastry, a native of Mysore and a luminary in the court of Maharaja Krishnaraja III and Maharaja Chamaraja X, is known as the "Father of Kannada theatre" (Kannada Nataka Pitamaha).[149] He authored dramas in Kannada and translated William Shakespeare's "Othello" to Shurasena Charite. His well-known translations from Sanskrit to Kannada are many and include Kalidasa and Abhignyana Shakuntala.[150]

Music

Under Maharaja Krishnaraja III and his successors – Chamaraja X, Krishnaraja IV and the last ruler, Jayachamaraja, the Mysore court came to be the largest and most renowned patron of music.[151] While the Tanjore and Travancore courts also extended great patronage and emphasised preservation of the art, the unique combination of royal patronage of individual musicians, the founding of music schools to kindle public interest and patronage of European music publishers and producers set Mysore apart.[152] Maharaja Krishnaraja III, himself a musician and musicologist of merit, composed several javalis (light lyrics) and devotional songs in Kannada under the title Anubhava pancharatna. His compositions bear the pen name (mudra) "Chamundi'" or '"Chamundeshwari'", in honour of the Wodeyar family deity.[153]

Under Krishnaraja IV, art received further patronage. A distinct school of music that gave importance to

The Mysore court was home to several renowned experts (

Architecture

The architectural style of courtly and royal structures in the kingdom underwent profound changes during British rule – a mingling of European traditions with native elements. The Hindu temples in the kingdom were built in typical South Indian

The

The

Most famous among the many temples built by the Wodeyars is the

Tipu Sultan built a wooden collonaded palace called the Dariya Daulat Palace (lit, "garden of the wealth of the sea") in Srirangapatna in 1784. Built in the Indo-Saracenic style, the palace is known for its intricate woodwork consisting of ornamental arches, striped columns floral designs, and paintings. The west wall of the palace is covered with murals depicting Tipu Sultan's victory over Colonel Baillie's army at Pollilur, near Kanchipuram in 1780. One mural shows Tipu enjoying the fragrance of a bouquet while the battle is in progress. In that painting, the French soldiers' moustaches distinguish them from the cleanshaven British soldiers.[181][182] Also in Srirangapatna is the Gumbaz mausoleum, built by Tipu Sultan in 1784. It houses the graves of Tipu and Hyder Ali. The granite base is capped with a dome built of brick and pilasters.[183]

-

Mysore Palace

-

The Gopura (tower) of the Chamundeshwari Temple on the Chamundi Hills. The temple is dedicated to Mysore's patron deity.

-

The Jaganmohan Palace at Mysore – now an art gallery which is home to some of Raja Ravi Varma's masterpieces

-

Tipu Sultan's tomb at Srirangapatna

-

VIPs.

Science and Technology in Mysore

Rocket Science & Rocket Artillery

The first iron-cased and metal-

According to Stephen Oliver Fought and John F. Guilmartin Jr. in Encyclopædia Britannica (2008):

The rockets were observed by Lieutenant General

Dr

Tipu Sultan's father had expanded on Mysore's use of rocketry, making critical innovations in the rockets themselves and the military logistics of their use. He deployed as many as 1,200 specialised troops in his army to operate rocket launchers. These men were skilled in operating the weapons and were trained to launch their rockets at an angle calculated from the diameter of the cylinder and the distance to the target. The rockets had twin side sharpened blades mounted on them, and when fired en masse, spun and wreaked significant damage against a large army. Tipu greatly expanded the use of rockets after Hyder's death, deploying as many as 5,000 rocketeers at a time.[189] The rockets deployed by Tipu during the Battle of Pollilur were much more advanced than those the British East India Company had previously seen, chiefly because of the use of iron tubes for holding the propellant; this enabled higher thrust and longer range for the missiles (up to 2 km range).[189][186]

British accounts describe the use of the rockets during the third and fourth wars.[190] During the climactic battle at Srirangapatna in 1799, British shells struck a magazine containing rockets, causing it to explode and send a towering cloud of black smoke with cascades of exploding white light rising from the battlements. After Tipu's defeat in the Fourth War, the British captured a number of the Mysorean rockets. These became influential in British rocket development, inspiring the Congreve rocket, which was soon put into use in the Napoleonic Wars.[186]

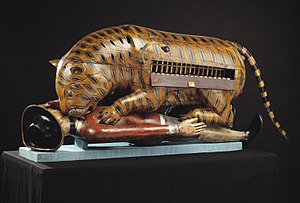

Tipu's Tiger

The automaton makes use of his emblem of the tiger and expresses his hatred of his enemy, the British of the

Military & War Artillery

See also

- List of Indian princely states

- Hyderabad State

- Mysorean invasion of Malabar

- Political integration of India

- Mughal Empire

References

- ^ Rajakaryaprasakta Rao Bahadur (1936), pg. 383

- ^ "Raja Wodeyar's Conquest of Srirangapatna". 26 March 2018. Archived from the original on 6 December 2022. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ISBN 9789004330795

- ISBN 9780190088897

- ^ Roddam Narasimha (May 1985). Rockets in Mysore and Britain, 1750–1850 A.D. Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Published by the National Aeronautical Laboratory.

- ^ Kamath (2001), pp. 11–12, pp. 226–227; Pranesh (2003), p. 11

- ^ Narasimhacharya (1988), p. 23

- ^ Subrahmanyam (2003), p. 64; Rice E.P. (1921), p. 89

- ^ Kamath (2001), p. 226

- ^ Rice B.L. (1897), p. 361

- ISBN 978-0-415-55449-7. Archivedfrom the original on 26 January 2024. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ Pranesh (2003), pp. 2–3

- ^ Wilks, Aiyangar in Aiyangar and Smith (1911), pp. 275–276

- ^ Aiyangar (1911), p. 275; Pranesh (2003), p. 2

- ^ Stein (1989), p. 82

- ^ Stein 1987, p. 82

- ^ Kamath (2001), p. 227

- ^ Subrahmanyam (2001), p. 67

- ^ a b c Subrahmanyam (2001), p. 68

- ^ Venkata Ramanappa, M. N. (1975), p. 200

- ^ Shama Rao in Kamath (2001), p. 227

- ^ a b c d e Venkata Ramanappa, M. N. (1975), p.201

- ^ a b Subrahmanyam (2001), p. 68; Kamath (2001), p. 228

- ^ a b Subrahmanyam (2001), p. 71

- ^ Kamath (2001), pp. 228–229

- ^ Subrahmanyam (2001), p. 69; Kamath (2001), pp. 228–229

- ^ Subrahmanyam (2001), p. 69

- ^ Subrahmanyam (2001), p. 70

- ^ Subrahmanyam (2001), pp. 70–71; Kamath (2001), p. 229

- ^ Pranesh (2003), pp. 44–45

- ^ a b c Kamath (2001), p. 230

- ^ Shama Rao in Kamath (2001), p. 233

- ^ Quote: "A military genius and a man of vigour, valour and resourcefulness" (Chopra et al. 2003, p. 76)

- ^ a b Venkata Ramanappa, M. N. (1975), p. 207

- ^ Chopra et al. (2003), p. 71, 76

- ^ Chopra et al. (2003), p. 55

- ^ a b c d Kamath (2001), p. 232

- ^ Chopra et al. (2003), p. 71

- ^ Chopra et al. (2003), p. 73

- ^ History Of Marathas By Grant Duff VOL 2. pp. 211–217.

- ^ ISBN 978-0-313-33536-5. Archivedfrom the original on 26 January 2024. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ^ Chopra et al. (2003), p. 74

- ^ Chopra et al. (2003), p. 75

- ^ Chopra et al. 2003, p. 75

- ^ Venkata Ramanappa, M. N. (1975), p. 211

- ISBN 9788131300343.

- ISBN 9788187879572

- ISBN 9788171547890, archivedfrom the original on 26 January 2024, retrieved 2 January 2022

- ^ a b Chopra et al. (2003), p. 78–79; Kamath (2001), p. 233

- ^ Chopra et al. (2003), pp. 75–76

- ^ a b Chopra et al. (2003), p. 77

- ISBN 9788187879572, archivedfrom the original on 26 January 2024, retrieved 16 June 2016

- ^ Chopra et al. (2003), pp. 79–80; Kamath (2001), pp. 233–234

- ^ Chopra et al. (2003), pp. 81–82

- ^ Kamath (2001), p. 249

- ^ a b Kamath (2001), p. 234

- ^ Venkata Ramanappa, M. N. (1975), p. 225

- ^ Quote: "The Diwan seems to pursue the wisest and the most benevolent course for the promotion of industry and opulence" (Gen. Wellesley in Kamath 2001, p. 249)

- ^ Venkata Ramanappa, M. N. (1975), pp. 226–229

- ^ Kamath (2001), p. 250

- ^ Venkata Ramanappa, M. N. (1975), pp. 229–231

- ^ Venkata Ramanappa, M. N. (1975), pp. 231–232

- ^ Lewis Rice, B., Report on the Mysore census (Bangalore: Mysore Government Press, 1881), p. 3

- ^ a b Kamath (2001), pp. 250–254

- ^ Rama Jois, M. 1984. Legal and constitutional history of India's ancient legal, judicial and constitutional system. Delhi: Universal Law Pub. Co. p. 597

- ^ Puttaswamaiah, K. 1980. The economic development of Karnataka is a treatise on continuity and change. New Delhi: Oxford & IBH. p. 3

- ^ "The Mysore duo Krishnaraja Wodeya IV & M. Visvesvaraya". India Today. Archived from the original on 24 October 2008. Retrieved 23 October 2007.

- ^ Pranesh (2003), p. 162

- ^ Kamath (2001), p. 261

- ^ "Instrument of Accession of the Maharajah of Mysore". Mysore State- Instrument of Accession and Standstill Agreement signed between Jaya Chamaraja Wadiyar. Ruler of Mysore State and the Dominion of India Archived 26 January 2024 at the Wayback Machine. New Delhi: Ministry of States, Government of India. 1947. p. 2. Retrieved 2 January 2024 – via National Archives of India.

- ^ Asian Recorder, Volume 20 (1974), p. 12263

- ^ Kamath (2001), p. 228; Venkata Ramanappa, M. N. (1975), p. 201

- ^ Venkata Ramanappa, M. N. (1975), p.203

- ^ Kamath (2001), pp. 228–229; Venkata Ramanappa, M. N. (1975), p. 203

- ^ a b Kamath (2001), p. 233

- ^ Kamath (2001), p. 235

- ^ a b Kamath (2001), p. 251

- ^ a b Kamath (2001), p. 252

- ^ Meyer, Sir William Stevenson, et al. The Imperial Gazetteer of India. Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1908–1931. v. 18, p. 228.

- ^ Kamath (2001), p. 254

- ^ a b Kamath (2001), pp. 254–255

- ^ a b c Kamath (2001), p. 257

- ^ Kamath (2001), p. 259

- ^ Indian Science Congress (2003), p. 139

- ^ a b Kamath (2001), p. 258

- ^ Indian Science Congress (2003), pp. 139–140

- ^ Kamath (2001), p. 260

- ^ Sastri (1955), p. 297–298

- ^ a b Chopra et al. (2003), p. 123

- ^ M. H. Gopal in Kamath 2001, p. 235

- ^ Kamath (2001), pp. 235–236

- ^ Kamath (2001), pp. 236–237

- ^ ISBN 978-8131300879. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ^ Chopra et al. (2003), p. 124

- ^ Chopra et al. (2003), p. 129

- ^ Chopra et al. (2003), p. 130

- ^ Kamath (2001), p. 286

- ^ Chopra et al. (2003), p. 132

- ^ Kamath (2001), p. 287

- ^ Kamath (2001), pp. 288–289

- ^ Chopra et al. (2003), p. 134

- ^ Rice E.P. (1921), p. 89

- ^ Pranesh (2003), p. 5, p. 16, p. 54

- ^ Nagaraj in Pollock (2003), p. 379

- ^ Kamath (2001), p. 229

- ^ Aiyangar and Smith (1911), p. 304

- ^ Pranesh (2003), p. 17

- ^ Aiyangar and Smith (1911), p. 290

- ^ Pranesh (2003), p. 4

- ^ Pranesh (2003), p. 44

- ^ a b Kamath (2001), pp. 229–230

- ^ Singh (2001), pp. 5782–5787

- ^ a b Sastri (1955), p. 396

- ^ Mohibul Hassan in Chopra et al., 2003, p. 82, part III

- ^ Chopra et al. (2003), p. 82

- ^ Kamath (2001), p. 237

- ^ Sastri (1955), p. 394

- ^ Kamath (2001), p. 278

- ^ Chopra et al. (2003), p. 185

- ^ Chopra et al. (2003), p. 186

- ^ Kamath (2001), pp. 278–279

- ^ Chopra et al. (2003), pp. 196–197, p. 202

- ^ Kamath (2001), p. 284

- ^ Kamath (2001), p. 275

- ^ Kamath (2001), pp. 279–280; Murthy (1992), p. 168

- ^ Kamath (2001), p. 281; Murthy (1992), p. 172

- ^ Murthy (1992), p. 169

- ^ a b Kamath (2001), p. 282

- ^ Pranesh (2003), p163

- ^ a b Kamath (2001), p. 283

- ^ Narasimhacharya (1988), pp. 23–27

- ^ Mukherjee (1999), p. 78; Narasimhacharya (1988), p. 23, p. 26

- ^ Kamath (2001), pp. 229–230; Pranesh (2003), preface chapter p(i)

- ^ Narasimhacharya (1988), pp. 23–26

- ^ Narasimhacharya (1988), p. 25

- ^ Kamath (2001), p. 281

- ^ Murthy (1992), p. 168–171; Kamath (2001), p. 280

- ^ Rice E.P. (1921), p. 90; Mukherjee (1999), p. 119

- ^ Kamath (2001), p. 227; Pranesh (2003), p. 11

- ^ Pranesh (2003), p. 20

- ^ Mukherjee (1999), p. 78; Pranesh (2003), p. 21

- ^ Mukherjee (1999), p. 143, p. 354, p. 133, p. 135; Narasimhacharya (1988), pp. 24–25

- ^ Pranesh (2003), pp. 33–34; Rice E.P. (1921), pp. 72–73, pp. 83–88, p. 91

- ^ Pranesh (2003), pp. 37–38

- ^ Pranesh (2003), p. 53

- ^ Narasimhacharya (1988), p. 26; Murthy (1992), p. 167; Pranesh (2003), p. 55

- ^ Murthy (1992), p. 167

- ^ Murthy (1992), p. 170

- ^ Pranesh (2003), p. 81

- ^ Sahitya Akademi (1988), p. 1077; Pranesh (2003), p. 82

- ^ a b c Weidman (2006), p. 66

- ^ Weidman (2006), p. 65

- ^ Pranesh (2003), p. 54

- ^ Pranesh (2003), p. xiii in author's note

- ^ Kamath (2001), p282

- ^ Weidman (2006), p. 67

- ^ Weidman (2006), p. 68

- ^ Pranesh (2003), p. 110

- ^ Bakshi (1996), p. 12; Kamath (2001), p. 282

- ^ Pranesh (2003), pp. 110–111

- ^ Satish Kamat (11 July 2002). "The final adjustment". Metro Plus Bangalore. The Hindu. Chennai, India. Archived from the original on 4 July 2003. Retrieved 10 October 2007.

- ^ Subramaniyan (2006), p. 199; Kamath (2001), p. 282

- ^ Pranesh (2003), p. 135

- ^ Pranesh (2003), p. 140

- ^ Subramaniyan (2006), p. 202; Kamath (2001), p. 282

- ^ Pranesh (2003), p. 170

- ^ Pranesh (2003), p. 214, 216

- ^ Pranesh (2003), p. 216

- ^ Michell, p. 69

- ^ Manchanda (2006), p. 158

- ^ Manchanda (2006), pp. 160–161

- ^ Manchanda (2006), p. 161

- ^ a b c Raman (1994), pp. 87–88

- ^ Raman (1994), pp. 83–84, pp. 91–92

- ^ Raman (1994), p. 84

- ^ Bradnock (2000), p. 294

- ^ Raman (1994), pp. 81–82

- ^ Raman (1994), p. 85

- ^ Raman (1996), p. 83

- ^ Michell p. 71

- ^ Raman (1994), p. 106

- ^ Abram et al. (2003), p. 225

- ^ Abram et al. (2003), pp. 225–226

- ^ Roddam Narasimha (1985). Rockets in Mysore and Britain, 1750–1850 A.D. Archived 27 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine National Aeronautical Laboratory and Indian Institute of Science.

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica (2008), "rocket and missile"

- ^ a b c Narasimha, Roddam (27 July 2011). "Rockets in Mysore and Britain, 1750–1850 A.D." (PDF). National Aeronautical Laboratory and Indian Institute of Science. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011.

- from the original on 26 January 2024. Retrieved 18 November 2023.

- ^ Zachariah, Mini Pant (7 November 2010). "Tipu's legend lives on". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- ^ a b "Over 5,000 'war rockets' of Tipu Sultan unearthed". Deccan Herald. 28 July 2018. Archived from the original on 30 September 2021. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ "How the Mysorean rocket helped Tipu Sultan's military might gain new heights". 5 August 2018. Archived from the original on 26 June 2023. Retrieved 20 November 2023.

- ^ "Tippoo's Tiger – European Romanticisms in Association". 9 August 2019. Archived from the original on 6 November 2023. Retrieved 6 November 2023.

- ^ Victoria & Albert Museum (2011). "Tipu's Tiger". London: Victoria & Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 1 August 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ]

- ^ Exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Bibliography

- Abram, David; Edwards, Nick; Ford, Mike; Sen, Devdan; Wooldridge, Beth (2003). South India. Rough Guides. ISBN 1-84353-103-8.

- ISBN 81-206-1850-5.

- Bakshi, Shiri Ram (1996). Gandhi and the Congress. New Delhi: Sarup and Sons. ISBN 81-85431-65-5.

- Bradnock, Robert (2000) [2000]. South India Handbook – The Travel Guide. Footprint Travel Guide. ISBN 1-900949-81-4.

- Chopra, P. N.; Ravindran, T. K.; Subrahmanian, N. (2003). History of South India (Ancient, Medieval and Modern) Part III. New Delhi: Sultan Chand and Sons. ISBN 81-219-0153-7.

- Indian Science Congress Association (various authors), Presidential Address, vol 1: 1914–1947 (2003). The Shaping of Indian Science. Orient Blackswan. ISBN 81-7371-432-0.)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link - OCLC 7796041.

- Manchanda, Bindu (2006) [2006]. Forts & Palaces of India: Sentinels of History. Roli Books Private Limited. ISBN 81-7436-381-5.

- Michell, George (17 August 1995). "Temple Architecture: The Kannada and Telugu zones". The New Cambridge History of India: Architecture and Art of Southern India. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-44110-2.

- Mukherjee, Sujit (1999) [1999]. A Dictionary of Indian Literature. Orient Blackswan. ISBN 81-250-1453-5.

- Murthy, K. Narasimha (1992). "Modern Kannada Literature". In George K.M (ed.). Modern Indian Literature:An Anthology – Vol 1. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 81-7201-324-8.

- Nagaraj, D.R. (2003) [2003]. "Critical Tensions in the History of Kannada Literary Culture". In Sheldon I. Pollock (ed.). Literary Cultures in History: Reconstructions from South Asia. Berkeley and London: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-22821-9.

- Narasimhacharya, R (1988) [1934]. History of Kannada Literature. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-0303-6.

- Pranesh, Meera Rajaram (2003) [2003]. Musical Composers during Wodeyar Dynasty (1638–1947 A.D.). Bangalore: Vee Emm. ISBN 978-8193101605.

- Raman, Afried (1994). Bangalore – Mysore: A Disha Guide. Bangalore: Orient Blackswan. ISBN 0-86311-431-8.

- Rice, E. P. (1921). Kannada Literature. New Delhi: (Facsimile Reprint 1982) Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-0063-0.

- ISBN 81-206-0977-8.

- ISBN 0-19-560686-8.

- Singh, Nagendra Kr (2001). Encyclopaedia of Jainism. Anmol Publications. ISBN 81-261-0691-3.

- ISBN 0-521-26693-9.

- Subrahmanyam, Sanjay (2001). "Warfare and State Finance in Wodeyar Mysore". In Subrahmanyam, Sanjay (ed.). Penumbral Visions. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. pp. 161–193. ISBN 978-0-472-11216-6.

- Subramaniyan, V.K. (2006) [2006]. 101 Mystics of India. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 81-7017-471-6.

- Various (1988) [1988]. Encyclopaedia of Indian literature – vol 2. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 81-260-1194-7.

- Venkata Ramanappa, M. N. (1975) [1975]. Outlines of South Indian history : with special reference to Karnataka. Delhi : Vikas Pub. House; London (38 Kennington La., SE11 4LS) : [Distributed by] Independent Pub. Co. ISBN 0-7069-0378-1.

- Weidman, Amanda J (2006) [2006]. Singing the Classical, Voicing the Modern. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-3620-0.

Further reading

- "India". Life. Time, Inc. 12 May 1941. pp. 94–103.

- Yazdani, Kaveh. India, Modernity and the Great Divergence: Mysore and Gujarat (17th to 19th C.) (Leiden: Brill), 2017. xxxi + 669 pp. online review Archived 11 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine