Charles Edward, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

| Charles Edward | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha | |||||

| Reign | 30 July 1900 – 14 November 1918 | ||||

| Predecessor | Alfred | ||||

| Successor | Monarchy abolished | ||||

| Regent | Ernst (30 July 1900 – 19 July 1905) | ||||

| Born | Prince Charles Edward, Duke of Albany 19 July 1884 Surrey, England | ||||

| Died | 6 March 1954 (aged 69) Coburg, West Germany | ||||

| Spouse | Princess Victoria Adelaide of Schleswig-Holstein | ||||

| Issue |

| ||||

| |||||

Princess Helena of Waldeck and Pyrmont | |||||

| Military career | |||||

| Allegiance |

| ||||

| Service/ | |||||

| President of the German Red Cross | |||||

| In office 1 December 1933 – 1945 | |||||

| Preceded by | Joachim von Winterfeldt-Menkin | ||||

| Succeeded by | Otto Gessler | ||||

Charles Edward (Leopold Charles Edward George Albert;

Charles Edward's parents were

The duke ascended the ducal throne in 1900 but reigned through a

During the 1920s, the former duke became a moral and financial supporter of violent far-right

Early life in Britain

Family

Charles Edward's father was

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, the

To each other, these impressive-looking figures might be known by such arch nicknames as Ducky or Mossie or Sossie, but among the group were a host of future kings, queens, emperors and empresses. In time, these direct descendants of Queen Victoria would sit on no less than ten European thrones. With good reason was the old Queen known as the 'Grandmama of Europe'. And in an age when it was still widely believed that monarchs were as important as they looked, it would be only natural... [for a child to assume it was] the most powerful clan on earth.[11]

Childhood

Charles Edward was brought up as a

Charles Edward, his mother, and his sister were surrounded by members of the wider royal family in proximity to Queen Victoria.[23] They frequently spent time with the Queen at her various estates.[24] Charles Edward was described as Victoria's favourite grandchild. The boy and his sister often visited Balmoral Castle where they prepared for their future positions. Victoria enjoyed her grandchildren acting out dramatic scenes which reflected the religious values she wanted to inculcate into them. Lewis Carroll, a family friend, described Charles Edward as a "perfect little prince" who was well-trained in court etiquette and ceremony.[25] Princess Helen also took her children on visits to her relatives in Germany and the Netherlands.[21][26] Public duties were a part of the royal family's functions, though Aronson suggests they were naive about the deeply unpleasant conditions much of the British population lived in. Charles Edward's mother was especially interested in social issues and, according to Alice, the children were encouraged to sympathise with others and engage in charity work.[27] Charles Edward developed an interest in military and royal occasions at a young age. He was given his first ceremonial position in the Seaforth Highlanders regiment of the British Army as a child. Shortly before his 13th birthday, Charles Edward participated in a parade for the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria. The boy climbed on the roof of Buckingham Palace to see the assembled crowds before the event. He was described in contemporary press reports as being the most well-received participant.[21]

Historian Hubertus Büschel indicates that the British royal family had high expectations for their young members' education.

First years in Germany

Selection as heir

Duke Alfred's only son, Prince Alfred, died in February 1899. The duke was in poor health and the question of who would be his successor became an issue for the family.[9][2] Alfred was seen as an inadequate foreigner among many members of the German governing elite and a number of German princes wanted to split up the duchy among themselves.[32] Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn, Victoria and Albert's third son, was initially heir presumptive. However, sections of the German press objected to a foreigner taking the throne, and Wilhelm II opposed a man who had served in the British army becoming ruler of a German state.[33][9] Arthur's son, Prince Arthur of Connaught, was at Eton with Charles Edward. Wilhelm II demanded a German education for the boy, but this was unacceptable to the Duke of Connaught. Thus both Charles Edward's uncle and cousin renounced their claims to the duchy, leaving Charles Edward next in line.[9]

The prince was named heir under family pressure.[7] There were reports in the American press that the younger Arthur had beaten Charles Edward up or threatened to do so if he did not accept the position.[34][35] The boy seemed unhappy with the change of situation that had been imposed on him. Rushton quotes him as saying: "I've got to go and be a beastly German prince." But the adults around him appear to have encouraged him to embrace his new role. His sister remembered their mother saying that "I have always tried to bring up Charlie as a good Englishman, and now I have to turn him into a good German". Field Marshal Frederick Roberts told him to "Try to be a good German!".[10] Only fourteen years old at the time, Charles Edward's young age, as well as his German mother and lack of his British father, meant that he was deemed able to assimilate into German society in a way an older man would not be. The local newspaper in Coburg praised the choice.[36] There was significant public interest in Germany in what happened to Charles Edward.[36][37] According to historian Alan R. Rushton, some Germans felt "it was now important for the English boy to become a German man and leader of his adopted land".[37]

Education

Charles Edward moved to Germany with his mother and sister when he was fifteen. He spoke little German. Duke Alfred wanted to separate Charles Edward from his mother, so she took her son to stay with her brother-in-law, King William II of Württemberg, and found him a tutor.[7] Helen then considered how he should be educated. The priority was reassuring Germans that he was being brought up in a properly German manner. Various members of the extended family made suggestions. Alfred wanted to be given responsibility for his heir but was considered too British. A school suggested by Queen Victoria's daughter Victoria was, according to Alice, felt to have too many Jewish students. Helen ultimately gave Wilhelm control over her son's education.[38][1]

According to Urbach, Wilhelm wanted to turn his young cousin into a "

Wilhelm II took such interest in Charles Edward's assimilation into German society that the latter was known in the Imperial Court as "the Emperor's seventh son". The Emperor loves to have fun with him [Charles Edward]. But what usually happens is that he pinches and puffs him so much that the poor little duke actually gets beaten up. Recently his bride, Princess Victoria and her parents were also present; This probably made it particularly embarrassing for the poor little duke, who almost fought back tears and had such an unhappy expression on his face the whole evening, as if he were about to be hanged the next morning.[47]

Regency

Charles Edward inherited the ducal throne of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha at the age of sixteen when his uncle Alfred died at the age of 55 in July 1900.

Charles Edward tried his best to assimilate while maintaining some links with Britain such as participating in

All the [German] newspapers sing the praises of the young Duke and describe his sympathetic character and bearing. Above all they are never tired of emphasising how German he has become, how he has completely forgotten the English training of his early youth, identifying himself in every way with the interests of Germany.[55]

Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha

Marriage and children

As Charles Edward was considered to have an "ambiguous" attitude towards women, according to Urbach, his family decided he needed an arranged marriage at a young age. Wilhelm II chose his niece Princess Victoria Adelaide of Schleswig-Holstein as the bride of Charles Edward. She was believed to be well-adjusted and loyal to Wilhelm's royal house.[40] Her nationality was seen as important and Victoria Adelaide lacked any non-German or Jewish ancestry.[56] The young man was told to propose to her and he obliged.[40] A degree of affection did exist between the young couple.[7][51] They married on 11 October 1905, at Glücksburg Castle, Schleswig-Holstein, and had five children.[2] Victoria Adelaide was described, in her grandson's memoirs, as the leading part in the marriage and Charles Edward would initially come to her for advice.[57] His entry in the ODNB comments that they were happy,[7] but Urbach indicates otherwise.[58]

Their children were:

The Coburg family are bright, happy children who lead a natural life, spending a great deal of their time in the open air in the fine grounds of their castle. They are very fond of riding. In the winter, which is a severe one in Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, they delight in ski-ing and other outdoor amusements suitable to snowy weather.[62]

Urbach discussed the family in later years. She comments that Charles Edward's children were frightened of their father, who treated them "like a military unit". She noted that the family often appear unhappy in photographs. His younger daughter, Princess Caroline Mathilde, claimed that her father had sexually abused her. The allegation was backed by one of her brothers. Charles Edward was often disappointed by his children's choice of romantic relationships, at a time when he was trying to use strategic marriages to improve the diminished reputation of his royal house.[63]

Peacetime reign

The young duke assumed full constitutional powers upon coming of age on 19 July 1905.[2] At his investiture, he read a speech promising his allegiance to the German Empire and was cheered on by onlookers after he publicly sampled local food. He was happy with his new territories, which he thought were pretty.[64] He joined various patriotic groups to emphasise his loyalties. However, according to Urbach, the duke lacked popularity. This was especially true in Gotha, an impoverished town with left-wing sympathies; to them he seemed absolutist. In Coburg, a wealthy and conservative town known for its intense nationalism, people were generally more sympathetic to Charles Edward, but disliked a sense of foreignness they detected about him. He continued to have an English accent. He faced criticism for keeping Scottish Terrier dogs and for always appearing in public with a police guard.[65]

Friedrich Facius described Charles Edward as initially a liberal who shifted in a more authoritarian direction. He was supportive of the emperor and understood the governmental institutions.[2] According to Rushton, the duke's political worldview was "conservative and nationalistic", reflecting what had been inculcated into him by Wilhelm II. He largely left governing to the cabinet he appointed. They used the motto "Everything as it has been" to describe their approach. Charles Edward frequently visited local events. He was interested in new forms of transportation, especially automobiles and airships. He invested in the creation of a new airship docking bay in Gotha, a decision that appeared commercially sensible.[66] He enthusiastically supported the court theatres in both towns and organised the restoration of the Veste Coburg, which was conducted between 1908 and 1924.[2] Charles Edward was a prominent figure in local civic life chairing many cultural or charitable organisations and offering patronage.[67] In 1910, he joined the "Reich Association against Social Democracy", a pro-monarchist political organisation.[68]

Charles Edward was anxious about how people viewed him, with his officials surveying public opinion. The duke frequently tried to emphasise his loyalty to Germany through displays of cultural traditions such as Christmas festivities and

The duke also became a major local landowner and had an annual income of about 2.5 million

Charles Edward had every reason to be happy with his life: a growing healthy family, minimal professional duties, the opportunity to live very well and associate with his friends and relatives at the upper echelons of society in Europe... As 1914 began, Charles Edward had not the slightest clue that the golden age of the European nobles was coming to a climax. He continued to hunt and travel, acting as an absolute sovereign... His life as a monarch seemed to exist in a parallel world that had little in common with the majority of his subjects.[73]

First World War

The

At the start of the war he publicly denounced Britain, accusing it of attacking Germany, and renounced his position as Colonel-in-chief of the Seaforth Highlanders.

In 1917, a law change in Coburg effectively banned Charles Edward's British relatives from succeeding to the duchy. That same year, the

The war placed severe burdens on the German population, and after mid-1918, the empire's military situation collapsed. By late in the year an armistice was signed and a revolution broke out in Germany.[87] On the morning of 9 November 1918, the Workers' and Soldiers' Council of Gotha declared Charles Edward deposed. On 11 November, his abdication was demanded in Coburg. Only on 14 November, later than most other ruling princes, did he formally announce that he had "ceased to rule" in both Gotha and Coburg. He did not explicitly renounce his throne.[2] According to Rushton, the slowness of Charles Edward's abdication was due to paranoia that he would be killed. However, the transition of power in Coburg was quite calm and orderly compared to some other parts of Germany. The German nobility were not physically attacked during the revolution, but the situation was deeply frightening and a cause of much resentment for them.[87]

Far-right advocate

Aftermath of the First World War

Urbach wrote that Charles Edward was not popular and still seen by some as English. By the end of the war, the left-wing, anti-royalist parts of the press had been nicknaming him "Mr Albany" in a reference to his foreign origins. But he could still live in Coburg fairly contentedly.[88] According to Rushton, he retained much of his prestige and was often seen by his former subjects as essentially still the duke. Coburg was a politically conservative town and the new post-war world was frightening for many people. The inhabitants continued to look to Charles Edward for guidance.[89] In 1919, he also lost his British titles, though some personal sympathy remained for him among the political establishment in the United Kingdom due to the way German nationality had been forced on him as a teenager.[7] He visited his mother and sister in London in 1921 but was generally unwanted in Britain.[90]

Charles Edward continued to describe himself as a monarchist in the post-First-World-War period.[90] He was said to want to return to political power as "King of Thuringia".[9] In practice, however, his enthusiasm for restoration was quite lukewarm. His emotional attachment to the German emperor largely ended with Wilhelm's exile. The former duke began to look for political options which he saw as a stronger alternative to the deposed German emperor.[90]

In 1919, his properties and collections in Coburg were transferred to the

Charles Edward also funded various

Early involvement with the Nazi Party

Charles Edward was a useful ally for the Nazis in the period before they gained power, with extensive links in Franconia and across Germany.[99] In 1929, his support contributed to Coburg becoming the first town in Germany to elect a Nazi Party council. The election had taken place due to a dispute about a Nazi supporter being dismissed from his job for attacking Jews. Charles Edward's visits to Nazi party events were covered in the local press, increasing the party's profile and prestige.[100] In 1932, he took part in the creation of the Harzburg Front, through which the German National People's Party and other groups with similar views became associated with the Nazi Party. He also publicly called on voters to support Hitler in the presidential election of 1932. While the Nazi party lost that election across Germany, they won in Coburg.[99]

Following the election of the Nazi Party locally in 1929, the Jewish population of Coburg experienced growing amounts of physical abuse and discrimination. Rushton writes that the former duke's publicly expressed beliefs and financial support contributed to the growth of hatred towards Jewish people in Coburg and Germany as a whole. It was widely known that Charles Edward and his wife were antisemitic. According to Rushton, Charles Edward would have been aware of the violent behaviour of the movements he was involved in but never objected. The First World War had convinced him of the merits of political violence.

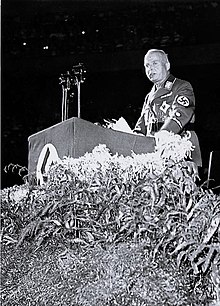

Nazi party figure

In 1933, the Nazi party came to power in Germany.[103] Charles Edward started flying the Nazi flag over Veste Coburg.[104] He formally joined the Nazi Party in March 1933; he also became an Obergruppenführer in the SA.[9] A photo collection of senior figures in the new regime published by a German private company included Charles Edward at number 43.[103] According to Urbach, he became a "highly honoured" member of the party, appearing in photographs with its senior members and setting up an office in Berlin which he could use to form relationships. She wrote that he was proud of his Nazi Party membership and that the SA uniform allowed him to feel more like his pre-war self. He lost his SA uniform after the Night of the Long Knives, this upset him a great deal, but he accepted the politically motivated murders. He was later given a Wehrmacht general's uniform.[105]

Charles Edward was made president of the National Socialist Automobile Association, an organisation which provided vehicles for the German state, including those used to carry out the Holocaust.[86] From 1936 to 1945, he served as a member of the Reichstag, representing the Nazi Party.[9] In appointment diaries, which he kept from 1932 to 1940, he often expressed his enthusiastic support for the party. For instance, he recorded the results of the 1936 one-party election in detail and praised the outcome. Büschel commented that the former duke appeared to see himself as fully a German by this stage in his life.[106]

German Red Cross and eugenics

On 1 December 1933 Charles Edward was appointed head of the Deutsches Rotes Kreuz (

Most evidence which could clarify the level of involvement of the German Red Cross in these events was destroyed, accidentally or deliberately, by the end of the war. While most transportation of victims was done by a proxy organisation created for that purpose, the German Red Cross was involved in transporting some of them. Many of the nurses who were involved in murdering disabled people were employees of the German Red Cross who had been indoctrinated by the organisation.

Unofficial diplomat

The Nazi regime made significant use of Charles Edward as an informal diplomat.

Charles Edward was particularly significant to Nazi attempts to cultivate pro-German sentiments among the

Charles Edward's ODNB entry argued that his advocacy had little success and that he failed to understand the degree to which the people he had grown up around now saw him as a foreigner.[7] In contrast, Urbach argued in her 2015 book that the strains experienced by British society during the interwar period had a radicalising effect on sections of the British elite and that there was significant sympathy for fascism, albeit discomfort with Nazism in particular, among the aristocracy. She wrote that Charles Edward reintegrated himself into aristocratic social life in Britain, with the help of his sister, and influenced prominent aristocrats and politicians. She suggested that Charles Edward may have had some influence on instances of appeasement of Germany in the 1930s, such as British acceptance of the German remilitarisation of the Rhineland and the Munich Agreement.[114]

Second World War

Although Charles Edward was too old for active service during the

Charles Edward probably ceased to act as an informal diplomat after 1940.

In April 1945 code breakers at

Postwar period and death

Trial and final years

After the end of the Second World War, Charles Edward was interned by the

In April 1946, Charles Edward's daughter Sibylla gave birth to a son,

Charles Edward's trial spanned four years and included two

Charles Edward spent the last years of his life in seclusion, forced into relative poverty by the fines he had been required to pay by the denazification tribunal, On the occasion of a regimental ball, an invitation was sent to the Duke, with a note from the C.O. (Lieut.-Colonel P. J. Johnston) saying that, owing to the distance, it was doubtful if he would be able to attend, but it was the wish of all officers of the battalion that their old Colonel-in-Chief should be asked. The Duke replied that, although his health did not allow him to accept, he was deeply touched by the invitation, "renewing old connections which existed between the Seaforth Highlanders and myself for so many years, and which I honestly hope and wish will not be severed again". He said he would be pleased to receive as guest any comrade who should happen to pass Coburg, where he lives, and signed himself "Charles Edward. Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, Duke of Albany."[146]

Death

Charles Edward died of cancer in his flat in Coburg on 6 March 1954, at the age of 69.[143] He had reportedly told his son Friedrich Josias that Queen Victoria had always wanted him to be a "good German".[147] His obituary in The Times commented that "... he was Hitler's man... Whether, and to what extent, he was admitted to the inner council of the Nazi gang is as yet an open question."[120] Representatives of various royal houses across Europe sent condolences but the British royal family did not comment.[148]

Charles Edward's funeral was held on 10th March and presided over by a

Legacy

The first biography of Charles Edward's life was written by an amateur historian called Rudolf Preisner from Coburg in 1977. The former duke's son Friedrich Josias wrote a letter to Preisner criticising the book. Among other errors, he felt that the book was overly sympathetic to his father, who he believed knew about the Holocaust. He wrote that his brother, Hubertus, had witnessed deportations of Jewish people to extermination camps and often talked about the subject with the family. Friedrich Josias planned to write a biography about his father, but never did so.[149]

In December 2007, Britain's Channel 4 aired an hour-long documentary about Charles Edward called Hitler's Favourite Royal. A review in The Guardian described the film as "A solid documentary on a feeble man and a wretched family."[150] Another review in The Telegraph suggested the documentary had been overly sympathetic to Charles Edward, stating that the "story emerged as a tale of pure tragedy. Which it undoubtedly was, in parts", but that he was depicted "As if the trauma of being elevated to a dukedom and losing it had somehow robbed him of his ability to tell right from wrong."[151]

Urbach wrote that there was some disagreement among the production team of the 2007 documentary, on whether Charles Edward should be portrayed as a man who struggled with politics in a country that was foreign to him, or as an ideological Nazi, and that this led to a contradictory depiction of his character. She said that the recovery of new evidence during the period between 2007 and 2015 showed that he was "obviously not a naive victim of circumstances but a very active supporter of Hitler". Urbach argued that Charles Edward had a similar kind of character to Hitler, commenting that the two men shared "ideologies and of course their

Rushton in his 2018 book about the former duke's relationship to the murder of disabled people, described Charles Edward's life as "the story of a man born to royalty who became ensnared in the politics of human destruction. It is a tragic story."[155] Rushton suggested there would have been risks to Charles Edward and his family if he had chosen to object to any actions of the regime, giving examples of other former nobles who were persecuted. Rushton noted that Charles Edward had already lost his status as a British Prince and German Duke, making his new identity as a Nazi party leader deeply emotionally important to him. Rushton argued that the factors affecting Charles Edward's behaviour were similar to many Germans. However, the historian also noted that the duke had a close friendship with Hitler and could have influenced him.[156]

Notes

- ^ Academically focused German secondary school

- ^ He used the German language version of his name (German: Leopold Carl Eduard Georg Albert) in Germany.[1] This article uses the English language version of his name throughout.

- ^ According to the Bank of England's model for tracking inflation, £6,000 in 1890 was the equivalent to £637,962.29 in 2023.[19]

- ^ Now located in Wiltshire.

- ^ Charles Edward says "Uncle Edward is it true that I should only have half of this cake?". It is a reference to Edward VII holding the title of Duke of Saxony, which was traditionally held by the Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha.

- ^ Russia was part of the Soviet Union, a communist state, at the time.

- ^ Charles Edward had been at Eton with Henderson and this photograph may have been taken at a meeting of the Anglo-German Fellowship that Henderson addressed in May 1937, shortly after his appointment as British ambassador.[116]

References

- ^ a b c Urbach 2017, p. 30.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Facius 1977.

- ^ Urbach 2017, p. 27.

- ^ Aronson 1981, p. 30.

- ^ Aronson 1981, p. 52.

- ^ Reynolds 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Zeepzat 2008.

- ^ Urbach 2017, pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Oltmann 2001.

- ^ a b c d e Rushton 2018, p. 12.

- ^ Aronson 1981, pp. 61–62.

- ^ "The Infant Duke Of Albany". Daily News (London). 5 December 1884. Retrieved 23 March 2023 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Burke & Burke 1885, p. 103.

- ^ Aronson 1981, p. 48.

- ^ a b Aronson 1981, p. 50.

- ^ a b Urbach 2017, p. 28.

- ^ Büschel 2016, p. 47.

- ^ Aronson 1981, p. 38.

- ^ "Inflation calculator". Bank of England. Retrieved 15 February 2024.

- ^ Aronson 1981, pp. 38, 49.

- ^ a b c d e f Büschel 2016, pp. 47, 49–52.

- ^ Aronson 1981, pp. 50–52, 58.

- ^ Rushton 2018, p. 11.

- ^ Aronson 1981, pp. 62–75.

- ^ Büschel 2016, pp. 49–52.

- ^ Aronson 1981, pp. 84–90.

- ^ Aronson 1981, pp. 96–99.

- ^ Aronson 1981, pp. 58.

- ^ Aronson 1981, p. 60.

- ^ Büschel 2016, p. 50.

- ^ Aronson 1981, p. 109.

- ^ Büschel 2016, p. 44.

- ^ Urbach 2017, pp. 28–29.

- ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- ^ a b "Kicked into the Kingdom". Wellsville Daily Reporter. 15 July 1905. p. 2.

- ^ a b Urbach 2017, p. 29.

- ^ a b c d Rushton 2018, p. 14.

- ^ Aronson 1981, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Aronson 1981, p. 112.

- ^ a b c d e Urbach 2017, p. 32.

- ^ Sandner 2004, p. 195.

- ^ a b Rushton 2018, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Aronson 1981, p. 118.

- ^ Urbach 2017, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Rushton 2018, p. 13.

- ^ Rushton 2018, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Rushton 2018, p. 54—55.

- ^ a b Urbach 2017, p. 31.

- ^ Rushton 2018, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Büschel 2016, pp. 55–56.

- ^ a b c Rushton 2018, p. 15.

- ^ a b Weir 2011, p. 314.

- ^ Rushton 2018, p. 12,15.

- ^ Urbach 2017, pp. 31–32.

- The British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Büschel 2016, pp. 56.

- ^ Saxe-Coburg and Gotha 2015, p. 51, 57.

- ^ Urbach 2017, pp. 158, 175.

- ^ Weir 2008, pp. 314–15.

- ^ Rushton 2018, p. 17.

- ^ Priesner 1977, pp. 90–94.

- ^ "Royal Children of Europe: Saxe-Coburg-Gotha". The Sphere. 11 July 1914. p. 24 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b c Urbach 2017, p. 178.

- ^ Rushton 2018, p. 16.

- ^ Urbach 2017, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Rushton 2018, p. 17, 18.

- ^ Rushton 2018, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Büschel 2016, p. 57.

- ^ a b c d Büschel 2016, pp. 56–60.

- ^ Rushton 2018, pp. 17–20.

- ^ "The Duke of Saxe-Coburg Inspects Veterans". Daily Mirror. 18 August 1910. p. 13 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Rushton 2018, p. 19.

- ^ a b c Urbach 2017, pp. 16–19, 28–29.

- ^ Rushton 2018, p. 28.

- ^ a b Rushton 2018, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Rushton 2018, p. 20.

- ^ a b Urbach 2017, p. 66.

- ^ Urbach 2017, p. 65.

- ^ Swift MacNeill 1916.

- ^ Palmer 1916, pp. 8.

- ^ "Traitor Peers". Taunton Courier and Western Advertiser. 2 April 1919. p. 1 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "The Scandal of our Traitor Dukes". Sunday Post. 30 March 1919. p. 22 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Foreign Legislation—Great Britain". American Bar Association Journal. Vol. 5. Chicago: American Bar Association. 1919. p. 289.

- ^ Rushton 2018, p. 21, 23.

- ^ Urbach 2017, p. 67.

- ^ a b c d Petropoulos 2018.

- ^ a b Rushton 2018, pp. 21–27.

- ^ Urbach 2017, p. 146.

- ^ a b c Rushton 2018, p. 29.

- ^ a b c Urbach 2017, p. 148.

- ^ Urbach 2017, pp. 46–49.

- ^ Urbach 2017, p. 147.

- ^ Urbach 2017, p. 144.

- ^ Urbach 2017, pp. 148–149.

- ^ Urbach 2017, pp. 145, 151–152.

- ^ a b Rushton 2018, pp. 29–37.

- ^ Urbach 2017, pp. 156–157.

- ^ Urbach 2017, p. 149.

- ^ a b Urbach 2017, pp. 175–177.

- ^ Urbach 2017, p. 58.

- ^ Urbach 2017, pp. 177–178.

- ^ a b Rushton 2018, pp. 48–49.

- ^ a b Rushton 2018, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Rushton 2018, p. 37.

- ^ Urbach 2017, pp. 59–60, 75.

- ^ Büschel 2016, pp. 133–138.

- ^ Rushton 2018, pp. 99–103.

- ^ Rushton 2018, pp. 61–66.

- ^ Rushton 2018, pp. 57–61.

- ^ Rushton 2018, pp. 67–98.

- ^ Rushton 2018, pp. 104–110.

- ^ Rushton 2018, p. 116,143-144.

- ^ Rushton 2018, pp. 112–115.

- ^ a b c Urbach 2017, pp. 179–207, 210.

- ^ Urbach 2017, pp. 199–201, 207.

- ^ Henderson 1940, p. 19.

- ^ Cadbury 2015, p. 53.

- ^ Urbach 2017, p. 195.

- ^ a b Urbach 2017, pp. 203–204.

- ^ a b c "The Duke of Saxe-Coburg". The Times. 8 March 1954. p. 10.

- ^ Rushton 2018, pp. 164–166.

- ^ Büschel 2016, pp. 138–139.

- ^ Büschel 2016, p. 255.

- ^ Mott 2019.

- ^ Urbach 2017, p. 114.

- ^ Büschel 2016, p. 138.

- ^ Urbach 2017, p. 210.

- ^ Urbach 2017, p. 214, 216.

- ^ Rushton 2018, p. 165.

- ^ Urbach 2017, p. 2, 310.

- ^ Rushton 2018, pp. 3–5.

- ^ Urbach 2017, pp. 309–210.

- ^ Urbach 2017, p. 311.

- ^ Rushton 2018, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Aronson 1981, pp. 428–229, 434–436.

- ^ Rudberg 1947, p. 43.

- ^ "Prince and opera star killed in plane crash". Ottawa Citizen. Associated Press. 24 January 1947. Retrieved 24 November 2014.

- ^ "Kungens liv i 60 år" [King's life for 60 years] (in Swedish). Royal Court of Sweden. Archived from the original on 10 August 2017. Retrieved 9 July 2020.

- ^ Rushton 2018, p. 7.

- ^ Urbach 2017, pp. 312–313.

- ^ Rushton 2018, p. 155.

- ^ Feuchtwanger 2006, p. 278.

- ^ a b Cadbury 2015, p. 306.

- ^ Büschel 2016, p. 259.

- ^ Rushton 2018, p. 172.

- ^ "Duke of Albany". The Scotsman. 27 January 1953. p. 6 – via The British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Büschel 2016, p. 260.

- ^ a b Büschel 2016, pp. 259–261.

- ^ Büschel 2016, p. 28.

- ^ Mangan 2007.

- ^ O'Donovan 2007.

- ^ Urbach 2017, p. 2, 145, 154.

- ^ Moorhouse 2015.

- ^ Büschel 2016, pp. 262–264.

- ^ Rushton 2018, p. 2.

- ^ Rushton 2018, pp. 166–172.

Bibliography

- ISBN 9780304307579.

- Burke, Bernard; Burke, John (1885). Genealogical and Heraldic Dictionary of the Peerage and Baronetage of the British Empire. Vol. 47. Burke's Peerage Limited.

- Büschel, Hubertus (2016). Hitlers adliger Diplomat [Hitler's royal diplomat] (in German). Frankfurt: S. Fischer Verlag. ISBN 9783100022615.

- ISBN 9781610394048– via Google Books.

- ISBN 9781852854614– via Google Books.

- Facius, Friedrich (1977). "Karl Eduard". Neue Deutsche Biographie.

- ISBN 9781789127850.

- Mangan, Lucy (7 December 2007). "Last night's TV". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- Mott, Sophia (2019). Dem Paradies so fern. Martha Liebermann [So far from paradise. Martha Liebermann] (in German). Berlin: Ebersbach & Simon. ISBN 9783869151724.

- O'Donovan, Gerald (7 December 2007). "Last night on television: Hitler's Favourite Royal (Channel 4) - Spoil (Channel 4)". The Telegraph. Retrieved 19 December 2022.

- Oltmann, Joachim (18 January 2001). "Seine Königliche Hoheit der Obergruppenführer" [His Royal Highness the [SA] group leader]. Zeit Online (in German).

- Palmer, Charles (5 August 1916). "Traitors Near the Throne". John Bull. British Newspaper Archive.

- ISSN 0002-8762– via Book Review Digest Plus (H.W. Wilson.

- Priesner, Rudolf (1977). Herzog Carl Eduard zwischen Deutschland und England: eine tragische Auseinandersetzung [Duke Carl Eduard between Germany and England: a tragic confrontation] (in German). Hohenloher Druck- und Verlagshaus. ISBN 9783873540637.

- doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/16475. (Subscription or UK public library membershiprequired.)

- Rudberg, Erik, ed. (1947). Svenska dagbladets årsbok 1946 [Svenska Dagsbladet Yearbook 1946] (in Swedish). Stockholm: SELIBR 283647.

- Rushton, Alan R. (2018). Charles Edward of Saxe-Coburg: The German Red Cross and the Plan to Kill "Unfit" Citizens 1933-1945. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 9781527513402.

- Sandner, Harald (2004). "II.8.0 Herzog Carl Eduard". Das Haus von Sachsen-Coburg und Gotha 1826 bis 2001 [The House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha 1826 to 2001] (in German). Andreas, Prinz von Sachsen-Coburg und Gotha (preface). Coburg: Neue Presse GmbH. ISBN 9783000085253.

- ISBN 9781944207007.

- Swift MacNeill, J. G. (11 April 1916). "A Slur on the House of Lords (letter to the editor)". The Times.

- ISBN 9780191008672.

- ISBN 9780099539735.

- Weir, Alison (18 April 2011). Britain's Royal Families: The Complete Genealogy. Random House. ISBN 9781446449110– via Google Books.

- ISBN 9780198614128. (Subscription or UK public library membershiprequired.)

Further reading

- Sandner, Harald (2010). Hitlers Herzog: Carl Eduard von Sachsen-Coburg und Gotha: die Biographie [Hitler's Duke: Carl Eduard of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha: The Biography]. Aachen.

External links

![]() Media related to Charles Edward, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Charles Edward, Duke of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha at Wikimedia Commons