Wallachia

Principality of Wallachia | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1330–1859 | |||||||||||||||

| Motto: Dreptate, Frăție "Justice, Brotherhood" (1848) | |||||||||||||||

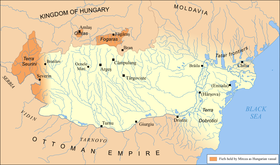

Wallachia in 1812 | |||||||||||||||

Wallachia in the late 18th century | |||||||||||||||

| Status |

| ||||||||||||||

| Capital |

| ||||||||||||||

| Common languages | |||||||||||||||

| Religion | Eastern Orthodox

Minority:

| ||||||||||||||

• c. 1290–c. 1310 | Radu Negru (first) | ||||||||||||||

• 1859–1862 | Alexandru Ioan Cuza (last) | ||||||||||||||

| Historical era |

| ||||||||||||||

| 1290[9] | |||||||||||||||

| 1330 | |||||||||||||||

• Ottoman suzerainty for the first time | 1417[10] | ||||||||||||||

• Long and Moldavian Magnate wars | 1593–1621 | ||||||||||||||

| 21 July [O.S. 10 July] 1774 | |||||||||||||||

| 14 September [O.S. 2 September] 1829 | |||||||||||||||

| 1834–1835 | |||||||||||||||

| 5 February [O.S. 24 January] 1859 | |||||||||||||||

| Currency | Austrian florin and others | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Romania | ||||||||||||||

Wallachia or Walachia (/wɒˈleɪkiə/;[11] Romanian: Țara Românească, lit. 'The Romanian Land' or 'The Romanian Country', pronounced [ˈt͡sara romɨˈne̯askə]; Old Romanian: Țeara Rumânească, Romanian Cyrillic alphabet: Цѣра Рꙋмѫнѣскъ, Greek: Βλαχία) is a historical and geographical region of modern-day Romania. It is situated north of the Lower Danube and south of the Southern Carpathians. Wallachia was traditionally divided into two sections, Muntenia (Greater Wallachia) and Oltenia (Lesser Wallachia). Dobruja could sometimes be considered a third section due to its proximity and brief rule over it. Wallachia as a whole is sometimes referred to as Muntenia through identification with the larger of the two traditional sections.

Wallachia was founded as a

In 1859, Wallachia united with

Etymology

The name Wallachia is an

In

For long periods after the 14th century, Wallachia was referred to as Vlashko (

Arabic chronicles from the 13th century had used the name of Wallachia instead of Bulgaria. They gave the coordinates of Wallachia and specified that Wallachia was named al-Awalak and the dwellers ulaqut or ulagh.[18]

The area of Oltenia in Wallachia was also known in Turkish as Kara-Eflak ("Black Wallachia") and Kuçuk-Eflak ("Little Wallachia"),[19] while the former has also been used for Moldavia.[20]

History

| History of Romania |

|---|

|

|

|

Ancient times

In the

The area was subject to Romanization also during the Migration Period, when most of present-day Romania was also invaded by Goths and Sarmatians known as the Chernyakhov culture, followed by waves of other nomads. In 328, the Romans built a bridge between Sucidava and Oescus (near Gigen) which indicates that there was a significant trade with the peoples north of the Danube. A short period of Roman rule in the area is attested under Emperor Constantine the Great,[21] after he attacked the Goths (who had settled north of the Danube) in 332. The period of Goth rule ended when the Huns arrived in the Pannonian Basin and, under Attila, attacked and destroyed some 170 settlements on both sides of the Danube.

Early Middle Ages

Byzantine influence is evident during the fifth to sixth century, such as the site at Ipotești–Cândești culture, but from the second half of the sixth century and in the seventh century, Slavs crossed the territory of Wallachia and settled in it, on their way to Byzantium, occupying the southern bank of the Danube.[22] In 593, the Byzantine commander-in-chief Priscus defeated Slavs, Avars and Gepids on future Wallachian territory, and, in 602, Slavs suffered a crucial defeat in the area; Flavius Mauricius Tiberius, who ordered his army to be deployed north of the Danube, encountered his troops' strong opposition.[23]

From its establishment in 681 to approximately the Hungarians' conquest of Transylvania at the end of the tenth century, the First Bulgarian Empire controlled the territory of Wallachia. With the decline and subsequent Byzantine conquest of Bulgaria (from the second half of the tenth century up to 1018), Wallachia came under the control of the Pechenegs, Turkic peoples who extended their rule west through the tenth and 11th century, until they were defeated around 1091, when the Cumans of southern Ruthenia took control of the lands of Wallachia.[24] Beginning with the tenth century, Byzantine, Bulgarian, Hungarian, and later Western sources mention the existence of small polities, possibly peopled by, among others, Vlachs led by knyazes and voivodes.

In 1241, during the Mongol invasion of Europe, Cuman domination was ended—a direct Mongol rule over Wallachia was not attested.[25] Part of Wallachia was probably briefly disputed by the Kingdom of Hungary and Bulgarians in the following period,[25] but it appears that the severe weakening of Hungarian authority during the Mongol attacks contributed to the establishment of the new and stronger polities attested in Wallachia for the following decades.[26]

Creation

One of the first written pieces of evidence of local voivodes is in connection with

Wallachia's creation, held by local traditions to have been the work of one

There is evidence that the

1400–1600

Mircea the Elder to Radu the Great

As the entire

The peace signed in 1428 inaugurated a period of internal crisis, as Dan had to defend himself against Radu II, who led the first in a series of boyar coalitions against established princes.[37] Victorious in 1431 (the year when the boyar-backed Alexander I Aldea took the throne), boyars were dealt successive blows by Vlad II Dracul (1436–1442; 1443–1447), who nevertheless attempted to compromise between the Ottoman Sultan and the Holy Roman Empire.[38]

The following decade was marked by the conflict between the rival houses of

Known as Vlad III the Impaler or Vlad III Dracula, he immediately put to death the boyars who had conspired against his father, and was characterized as both a national hero and a cruel tyrant.[39] He was cheered for restoring order to a destabilized principality, yet showed no mercy toward thieves, murderers or anyone who plotted against his rule. Vlad demonstrated his intolerance for criminals by utilizing impalement as a form of execution. Vlad fiercely resisted Ottoman rule, having both repelled the Ottomans and been pushed back several times.

The Transylvanian Saxons were also furious with him for strengthening the borders of Wallachia, which interfered with their control of trade routes. In retaliation, the Saxons distributed grotesque poems of cruelty and other propaganda, demonizing Vlad III Dracula as a drinker of blood.[40] These tales strongly influenced an eruption of vampiric fiction throughout the West and, in particular, Germany. They also inspired the main character in the 1897 Gothic novel Dracula by Bram Stoker.[41][self-published source?]

In 1462, Vlad III was defeated by Mehmed the Conqueror's during his offensive at the

Mihnea cel Rău to Petru Cercel

The late 15th century saw the ascension of the powerful

Ottoman suzerainty remained virtually unchallenged throughout the following 90 years.

The Ottoman Empire increasingly relied on Wallachia and Moldavia for the supply and maintenance of its

17th century

Initially profiting from Ottoman support,

The last stage in the

Russo-Turkish Wars and the Phanariotes

Wallachia became a target for

Immediately following the deposition of Prince Ștefan, the Ottomans renounced the purely nominal

In parallel, Wallachia became the battleground in a succession of wars between the Ottomans on one side and Russia or the Habsburg monarchy on the other. Mavrocordatos himself was deposed by a boyar rebellion, and arrested by Habsburg troops during the

In 1768, during the

Habsburg troops, under

From Wallachia to Romania

Early 19th century

The death of prince

On 21 March 1821 Vladimirescu entered Bucharest. For the following weeks, relations between him and his allies worsened, especially after he sought an agreement with the Ottomans;

The 1829

1840s–1850s

Opposition to Ghica's arbitrary and highly

Briefly under renewed Russian occupation during the

After an intense campaign, a formal union was ultimately granted: nevertheless, elections for the

Those elected changed their allegiance after a mass protest of Bucharest crowds,

Society

Slavery

The exact origins of slavery in Wallachia are not known. Slavery was a common

Traditionally, Roma slaves were divided into three categories. The smallest was owned by the hospodars, and went by the Romanian-language name of țigani domnești ("Gypsies belonging to the lord"). The two other categories comprised țigani mănăstirești ("Gypsies belonging to the monasteries"), who were the property of Romanian Orthodox and Greek Orthodox monasteries, and țigani boierești ("Gypsies belonging to the boyars"), who were enslaved by the category of landowners.[96][99]

The abolition of slavery was carried out following a campaign by young revolutionaries who embraced the liberal ideas of the Enlightenment. The earliest law which freed a category of slaves was in March 1843, which transferred the control of the state slaves owned by the prison authority to the local authorities, leading to their sedentarizing and becoming peasants. During the Wallachian Revolution of 1848, the agenda of the Provisional Government included the emancipation (dezrobire) of the Roma as one of the main social demands. By the 1850s the movement gained support from almost the whole of Romanian society, and the law from February 1856 emancipated all slaves to the status of taxpayers (citizens).[95][96]

Military forces

Geography

With an area of approximately 77,000 km2 (30,000 sq mi), Wallachia is situated north of the

Wallachia's traditional border with

), which are generally not considered part of Wallachia proper.The capital city changed over time, from Câmpulung to Curtea de Argeș, then to Târgoviște and, after the late 17th century, to Bucharest.

Map gallery

-

Wallachia, as shown on a wider map of the Black Sea (mid 16th century)

-

Wallachia, as part of the Holy League's Orthodox states

-

The Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia in 1786, as depicted on an Italian map by G. Pittori (after the geographer Giovanni Antonio Rizzi Zannoni)

-

F.J.J., von Reilly, Das Furstenthum Walachey, Viena, 1789

-

Salt trade in Wallachia between the 16th and 19th centuries

-

The region of Wallachia within contemporary Romania

Population

Historical population

Contemporary historians estimate the population of Wallachia in the 15th century at 500,000 people.[100] In 1859, the population of Wallachia was 2,400,921 (1,586,596 in Muntenia and 814,325 in Oltenia).[101]

Current population

According to the latest

Cities

The largest cities (as per the 2011 census) in the Wallachia region are:

- Bucharest (1,883,425)

- Craiova (269,506)

- Ploiești (209,945)

- Brăila (180,302)

- Pitești (155,383)

- Buzău (115,494)

- Drobeta-Turnu Severin (92,617)

- Râmnicu Vâlcea (92,573)

See also

- History of Bucharest

- List of rulers of Wallachia

- Balkan–Danubian culture

- Bulgarian lands across the Danube

Notes

References

- ^ Walachia Archived 19 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine at britannica.com

- ^ a b Protectorate Archived 14 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine at britannica.com

- ISBN 9781741044782. Archived from the original on 16 July 2023. Retrieved 11 November 2017 – via Google Books.

- ISBN 973-95711-2-3

- ^ "Tout ce pays: la Wallachie, la Moldavie et la plus part de la Transylvanie, a esté peuplé des colonies romaines du temps de Trajan l'empereur... Ceux du pays se disent vrais successeurs des Romains et nomment leur parler romanechte, c'est-à-dire romain... " in Voyage fait par moy, Pierre Lescalopier l'an 1574 de Venise a Constantinople, in: Paul Cernovodeanu, Studii și materiale de istorie medievală, IV, 1960, p. 444

- ^ Panaitescu, Petre P. (1965). Începuturile şi biruinţa scrisului în limba română (in Romanian). Editura Academiei Bucureşti. p. 5.

- ISBN 9780230583474. Archivedfrom the original on 16 July 2023. Retrieved 29 November 2018.

- ISBN 9780313274978. Archivedfrom the original on 16 July 2023. Retrieved 29 November 2018.

- ^ Brătianu 1980, p. 93.

- ^ a b Giurescu, Istoria Românilor, p. 481

- ^ "Wallachia". Dictionary.com Unabridged (Online). n.d. Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ Dinu C. Giurescu, "Istoria ilustrată a românilor", Editura Sport-Turism, Bucharest, 1981, p. 236

- ^ "Ioan-Aurel Pop, Istoria și semnificația numelor de român/valah și România/Valahia, reception speech at the Romanian Academy, delivered on 29 Mai 2013 in public session, Bucharest, 2013, pp. 18–21". Archived from the original on 18 October 2018. Retrieved 23 July 2019. See also I.-A. Pop, "Kleine Geschichte der Ethnonyme Rumäne (Rumänien) und Walache (Walachei)," I-II, Transylvanian Review, vol. XIII, no. 2 (Summer 2014): 68–86 and no. 3 (Autumn 2014): 81–87.

- ^ Arvinte, Vasile (1983). Român, românesc, România. București: Editura Științifică și Enciclopedică. p. 52.

- ^ A multikulturális Erdély középkori gyökerei – Tiszatáj 55. évfolyam, 11. szám. 2001. november, Kristó Gyula – The medieval roots of the multicultural Transylvania – Tiszatáj 55. year. 11th issue November 2001, Gyula Kristó

- ^ "Havasalföld és Moldva megalapítása és megszervezése". Romansagtortenet.hupont.hu. Archived from the original on 30 November 2017. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ Mann, S. (1957). An English-Albanian Dictionary. University Press. p. 129

- ^ Dimitri Korobeinikov, A broken mirror: the Kipchak world in the thirteenth century. In the volume: The other Europe from the Middle Ages, Edited by Florin Curta, Brill 2008, p. 394

- ISBN 978-1-55876-383-8. Archivedfrom the original on 16 July 2023. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ Johann Filstich (1979). Tentamen historiae Vallachicae. Editura Științifică și Enciclopedică. p. 39. Archived from the original on 16 July 2023. Retrieved 8 April 2018.

- ^ Giurescu, p. 37; Ștefănescu, p. 155

- ^ Giurescu, p. 38

- ^ Warren Treadgold, A Concise History of Byzantium, New York, St Martin's Press, 2001

- ^ Giurescu, pp. 39–40

- ^ a b Giurescu, p. 39

- ^ Ștefănescu, p. 111

- ^ Ștefănescu, p. 114

- ^ Ștefănescu, p. 119

- ^ Павлов, Пламен. "За северната граница на Второто българско царство през XIII-XIV в." (in Bulgarian). LiterNet. Archived from the original on 31 January 2020. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

- ^ Ștefănescu, p. 94

- ^ Ștefănescu, pp. 93–94

- ISBN 973-675-278-X

- ^ Ștefănescu, p. 139

- ^ Ștefănescu, p. 97

- ^ Giurescu, Istoria Românilor, p. 479

- ^ Ștefănescu, p. 105

- ^ Ștefănescu, pp. 105–106

- ^ Ștefănescu, p. 106

- ^ Cazacu 2017, pp. 199–202.

- ^ Gerhild Scholz Williams; William Layher (eds.). Consuming News: Newspapers and Print Culture in Early Modern Europe (1500–1800). pp. 14–34. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- ]

- ^ Ștefănescu, pp. 115–118

- ^ Ștefănescu, pp. 117–118, 125

- ^ Ștefănescu, p. 146

- ^ Ștefănescu, pp. 140–141

- ^ Ștefănescu, pp. 141–144

- ^ a b Ștefănescu, pp. 144–145

- ^ Ștefănescu, p. 162

- ^ Ștefănescu, pp. 163–164

- ^ Berza; Djuvara, pp. 24–26

- ^ Ștefănescu, pp. 169–180

- ^ "CÃLIN GOINA : How the State Shaped the Nation : an Essay on the Making of the Romanian Nation" (PDF). Epa.oszk.hu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 January 2007. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ Rezachevici, Constantin, Mihai Viteazul et la "Dacie" de Sigismund Báthory en 1595, Ed. Argessis, 2003, 12, pp. 155–164

- ^ Giurescu, pp. 65, 68

- ^ Giurescu, pp. 68–69, 73–75

- ^ Giurescu, pp. 68–69, 78, 268

- ^ Giurescu, p. 74

- ^ Giurescu, p. 78

- ^ Giurescu, pp. 78–79

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 31, 157, 336

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 31, 336

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 31–32

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 67–70

- ^ Djuvara, p. 124

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 48, 92; Giurescu, pp. 94–96

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 48, 68, 91–92, 227–228, 254–256; Giurescu, p. 93

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 59, 71; Giurescu, p. 93

- ^ Djuvara, p. 285; Giurescu, pp. 98–99

- ^ Berza

- ^ Djuvara, p. 76

- ^ Giurescu, pp. 105–106

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 17–19, 282; Giurescu, p. 107

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 284–286; Giurescu, pp. 107–109

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 165, 168–169; Giurescu, p. 252

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 184–187; Giurescu, pp. 114, 115, 288

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 89, 299

- ^ Djuvara, p. 297

- ^ Giurescu, p. 115

- ^ Djuvara, p. 298

- ^ Djuvara, p. 301; Giurescu, pp. 116–117

- ^ Djuvara, p. 307

- ^ Djuvara, p. 321

- ^ Giurescu, pp. 122, 127

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 262, 324; Giurescu, pp. 127, 266

- ^ Djuvara, p. 323

- ^ Djuvara, pp. 323–324; Giurescu, pp. 122–127

- ^ Djuvara, p. 325

- ^ Djuvara, p. 329; Giurescu, p. 134

- ^ Djuvara, p. 330; Giurescu, pp. 132–133

- ^ Djuvara, p. 331; Giurescu, pp. 133–134

- ^ a b Djuvara, p. 331; Giurescu, pp. 136–137

- ^ "Decretul No. 1 al Guvernului provisoriu al Țării-Românesci". Archived from the original on 1 March 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Giurescu, pp. 139–141

- ^ a b Giurescu, p. 142

- ^ ISBN 963-9241-84-9

- ^ ISBN 973-28-0523-4(in Romanian)

- ISBN 978-606-624-568-5. Archived(PDF) from the original on 3 April 2016.

- ^ Ștefan Ștefănescu, Istoria medie a României, Vol. I, Editura Universității din București, Bucharest, 1991 (in Romanian)

- ISBN 1-902806-07-7

- ^ East Central Europe in the Middle Ages, 1000–1500, Jean W. Sedlar, p. 255, 1994

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 June 2012. Retrieved 17 January 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Institutul Național de Statistică". Recensamant.ro. Archived from the original on 25 March 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

Bibliography

- Berza, Mihai. "Haraciul Moldovei și al Țării Românești în sec. XV–XIX", in Studii și Materiale de Istorie Medie, II, 1957, pp. 7–47.

- Brătianu, Gheorghe I (1980). Tradiția istorică despre întemeierea statelor românești (The Historical Tradition of the Foundation of the Romanian States). Editura Eminescu.

- Cazacu, Matei (2017). Reinert, Stephen W. (ed.). Dracula. East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450. Vol. 46. Translated by Brinton, Alice; Healey, Catherine; Mordarski, Nicole; Reinert, Stephen W. ISBN 978-90-04-34921-6.

- Djuvara, Neagu. Între Orient și Occident. Țările române la începutul epocii moderne, Humanitas, Bucharest, 1995.

- Giurescu, Constantin. Istoria Românilor, Vol. I, 5th edition, Bucharest, 1946.

- Giurescu, Constantin. Istoria Bucureștilor. Din cele mai vechi timpuri pînă în zilele noastre, ed. Pentru Literatură, Bucharest, 1966.

- Ștefănescu, Ștefan. Istoria medie a României, Vol. I, Bucharest, 1991.

External links

![]() Media related to Wallachia at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Wallachia at Wikimedia Commons